Electricity, modernity and tradition during Irish rural electrification, 1940-1970

Institute of Art, Design and Technology, Dun Laoghaire, Ireland.

sorchaobrien[at]gmail.com

@_sorcha

@electricirishhomes

ESB Archive; Kingston University, London; Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), UK; National Museum of Ireland – Country Life.

The arrival of widespread domestic electricity in rural Ireland was spread over two decades in the 1950s and 1960s, where the Electricity Supply Board (ESB) rolled out an electrical grid across the State. This energy transition was warmly welcomed by the women of rural Ireland, particularly for the relief it afforded for the continual drudgery of cooking on turf and coal fires, washing and cleaning by hand and using well or hand-pumped water. The poor economic situation of the state in the 1950s meant that only a restricted range of appliances were sold by the ESB or commercial shops, but initial fears about electricity were overcome by ESB advertising, however it made a real physical difference to women’s lives in a country with very prescribed and restricted social roles available to women. Coming from the discipline of design history, this article will look at the tangible evidence of appliances and kitchens changed by this energy transition. It will make use of oral history testimony gathered from a group of older women who were rural housewives in 1950s and 1960s Ireland, using this to consider the multi-layered meanings and emotions associated with these domestic electrical appliances, as well as considering what we can learn from women who have lived through a major energy transition.

Plan of the article

- Introduction

- Materiality, Design and Oral History

- Rural Electrification in Ireland

- ESB pamphlet promotion of rural electrification

- ESB television advertisements

- The Irish Countrywomen’s Association

- ESB/ICA model kitchen at the 1957 Spring Show

- Electricity and Religion: The Sacred Heart Lamp

- The Electrification of the Sacred Heart

- Conclusion

Introduction

MO: Well, I suppose looking back on it, it made things a lot easier, right? But at the time you were used to the life you had. Do you know what I mean?

SO: Yes.

MO: And everything was new and a lot of the things, like, it took you a while to get used to them, do you know? But gradually, you know, you got into it and it did, it did improve things an awful lot, you know, yes.1

The introduction of widespread electricity to rural Ireland in the 1950s and 1960s was a slow, arduous process, which involved promoting a new technology to a largely conservative rural population. The construction of the Ardnacrusha hydro-electric power station in the 1920s had been successfully positioned as an Irish post-colonial project, despite being constructed by the German company Siemens, and the intervening years had involved the development of further power stations and a cadre of native Irish engineering staff.2

To look at how the Electricity Supply Board (ESB) positioned their offerings to this rural population, it is important not to just look at the official narrative of the ESB itself, but also the broader social and cultural forces at play. This article will look at the material traces of both the ESB publicity campaign itself and at the role that electricity played in ‘upgrading’ pre-existing religious traditions and rituals. It frames these using object focused approaches from within design history, which consider the surviving material traces of objects from this time period, as well as their two dimensional representations. These design history approaches are useful for understanding the effect that physical and visual experiences can have on people, both in terms of buying decisions, everyday life and cultural attitudes. Historiographically, overlaps between design history and technology history go back to Siegfried Giedion’s Mechanization Takes Command, which is claimed by both disciplines as a foundational text.3 Throughout dialogue with material culture and other social sciences in recent decades, analysis of the physical object has remained central to the discipline, picking up on visual and material cues often glossed over by more traditional historical scholarship. This emphasis on the physical is complemented by the use of oral history, itself a non-physical discipline, but one which also works outside official narratives and which offers insights into emotions and meanings which may not be accessible otherwise. The article combines these two very different approaches, physical and spoken, into an analysis of rural electrification which complements the broader systems-based approaches to the study of Irish rural electrification and to energy history itself. The consideration of religious artefacts such as the Sacred Heart lamp provides a particularly appropriate case study, as both methods are used to analyse the meanings attached to physical objects, and how people used them to navigate their world, physically, but also in terms of meanings, values and aspirations.

Back to topMateriality, Design and Oral History

Design history, broadly defined, has focussed on the object since the development of the discipline from art history in the 1970s. This focus has historically been broadened by engagement with ideas from social sciences such as anthropology, archaeology and ethnography, with material culture a particularly strong influence. Methodologically, this expansion has been balanced by influences from critical and cultural theory, but retained its grounding in the physicality of real things and how they come to be made, dispersed and used.4 It specialises in the material traces of the more recent past, where is it often possible to talk to, read the writings of or look at the drawings of the people who designed these objects, as well as those who promoted or used them. Because of the political nature of most of the world in recent centuries, much of this focuses on objects created within the capitalist system, but the expansion of thinking effected by material culture has meant that it includes objects from pre-capitalist as well as socialist and communist systems, as well as utopian attempts to create new systems. While the traditional focus within the discipline has been on the agency of the designer, this cross-disciplinary dialogue has meant that this focus was first expanded out to other categories of humans (such as users) and then to the object and other elements of the system. The continued focus on the object, its properties and interactions, has meant that the intractability of matter and the difficulties of encouraging it into physical form have continued to play a role in the consideration of design as an activity that is embedded into systems of making, economics, politics, promotion, use and re-use, but also value, meaning and emotion. This is also not just a quality of the singular object, but the ‘gathering’ of objects, whether planned as a cohesive whole or accumulating due to less obvious forces.5

The role of culture and cultural specificity has been a theme throughout much design history writing, with the nation-state playing a particular role in the analysis, from overt displays such as flags and stamps, to the subtler manifestations in the everyday rhythms of street, workplace and home of a particular time and place.6 These ‘gatherings’ of objects work as agents in their own rights, sometimes pushing events in a cohesive manner, but as often not, with the inert nature of physical form exerting drag on the world of ideas and aspirations. This paper considers two such ‘gatherings’ of objects, both of which struggle to negotiate the ideas of ‘modernity’ in a mid-century Irish context, particularly where attempts to design a model kitchen that is still recognisable ‘Irish’ negotiate a heritage and traditional forms that are resistant to change and outside influence. Irish design history, in particular, has employed the ideas of Clifford Geertz on the process of nation-building to theorise the interplay between ideas of ‘essentialism’, concerned with tradition, heritage, religion, language and ethnicity; and ‘epochalism’, the ‘spirit of the age’, universalism, science and technology, the future and modernity.7 How these ideas are balanced within the imagining of any particular nation play out through their physical manifestations. This is particularly important in the Irish case, where designed objects are created both as materialisations of a desired or imagined Irish identity, but also in reaction to the colonial experience. They inherit a binary opposition where the universal, the urban and the technological were still considered to be ‘British’ and problematic, thirty years after the messy and partial independence of part of the island. The shifts in economic and social policy as the Irish Free State become a Republic in 1949 and faced the shortages and challenges of the post-war period, both internal and external, meant that the particular dialogue between essentialism and epochalism gave the products of Irish society and culture their specific national characteristics. This influenced the materials and tools available for manufacturing in the State, as well as the distribution mechanisms available, and the meanings and associations of electrical appliances. This is particularly important when ‘being modern’ was seen as both desirable and slightly worrying at the same time.

These meanings and associations have often been researched through surviving written documents, often through archives and libraries. While this remains an important historical record, it only represents the part of the written record that was deemed suitable for preservation, and is heavily biased towards official sources as a result. In terms of design history, it is extremely useful for documenting official government policies, organisational structures and decision-making, and other political and economic factors. However, it is much more difficult to get a sense of the ideas and opinions of ordinary people through this route, although they may be approximated through newspaper and magazine articles.8 Oral history, as a method, is better placed to try and disinter some of these ideas and opinions, value judgements and approaches, at least within living memory. While it is intrinsically a human-centric approach, it is one that can tell us much about the subtle interplay between official systems and individual reactions, spreading the location of agency out from official organisations to a broader spread of society. It is, of course, not the same as ‘being there’, of the historical desire to understand some kind of ‘truth’, as the ideas and opinions are still filtered through the perceptions of individuals who may or may not be representative of a social group. In addition, the passage of time must be taken into account, as both memory and the construction of narratives play a transformative role in how the past is understood by the individual, as well as the historian.9 This focus on the intangible histories plays a complementary role to that of design history/ material culture and more traditional historical archival approaches, widening out the focus of the discussion.

Back to topRural Electrification in Ireland

The archival histories of rural electrification in Ireland tell a story about organisational and governmental triumph over adversity, in order to bring light to the nation.10 They locate this project in post-war Ireland, where the pressures of post-colonial independence from Britain meant that exploiting any native power sources was desirable from both economic and ideological standpoints. The Electricity Supply Board (ESB) had been formed in the 1920s to run the first Irish hydro-electric power station Ardnacrusha, but their long-term plan to increase generation capacity had been interrupted by ‘The Emergency’, as World War II was called in neutral Ireland. This was to be complemented by the electrification of Irish homes and places of work, a project that was complicated by the high percentage of isolated rural dwellings and a population uneducated about science, let alone electricity, with many still cooking and heating their homes with open turf fires. Supported by both conservative party Fianna Fáil and more left-wing inter-party governments as a way of reducing emigration, especially amongst young women, the main electrification project ran from the late 1940s until the mid-1960s, with a smaller post-development infill project running into the mid-1970s. It also coincided with a move from the protectionist fiscal policies of the de Valera era towards the more outward looking and modernising approach promoted by Seán Lemass, which are credited with the gradual economic expansion of the 1960s and Ireland’s eventual accession into the European Economic Community in 1973.11

In addition to the actual infrastructural work of building hydroelectric and peat or gas-fuelled power stations and running power cables out to remote townlands, the ESB were also heavily involved with promoting electricity as a positive force in Irish life. The organisation had pioneered ‘American’ publicity methods in Ireland from the very start, appointing a PR director and forming a Publicity Department as early as 1927.12 The process of individually canvassing houses within an area for sign-ups to ‘the light’ meant that its staff had an in-depth appreciation for the lack of understanding amongst the rural Irish population of this new technology, given that the majority of the population left education by 14, without any teaching of science. This led to a number of strategies being developed, both ad hoc and institutional, in order to convince the average Irish farmer that his house would be brighter and warmer, his work easier and that electrical efficiencies would make the financial outlay worth it. It is notable that the bean an tí or ‘woman of the house’ rarely needed much convincing, given the back-breaking drudgery involved in running large farm households on well water, gas or oil lamps, open peat fires or possibly an Aga stove for the better off. Despite the best efforts of the women of the revolutionary period, the highly gendered roles of the late 19th century had survived in Irish society, having never been seriously threatened by war work, as in other European countries. The dominant influence of Catholic morality meant that ‘women’s place in the home’ had been written directly into the 1937 Constitution, conflating the role of ‘woman’ and ‘mother’ to produce an aspiration that all women would be mothers and not work outside the home unless forced to by ‘economic necessity’.13 As a result, rural Irish women were much more enthusiastic about electricity than their husbands, needing much less convincing that consistent bright light, electrical cookers and irons, as well as electrically pumped running water, would make their lives easier and reduce the numbers of their daughters emigrating to Britain or America.

Back to topESB pamphlet promotion of rural electrification

Part of the ESB’s efforts to educate and inform the Irish public included a number of informational pamphlets that were published throughout the 1950s and 1960s on topics such as heating the home and the benefits of hot water and electric kettles, as well as electric grain grinding and infra-red lamps for raising poultry.14 One type of pamphlet focused on the concept of electrical units, and the 1954 publication How Units Can Help demonstrates how the practical benefits of using a variety of electrical appliances around the home and farm. It breaks down the concept of the unit charge on top of the basic Fixed Charge and how the economic use of unit charges could enable financial savings and even profits. It divides its attention between a male and female audience, who are very clearly coded into separate pages on farm and home domains (see Fig 1), with the female figure shown in conjunction with the home, mirroring the male figure in the farmyard. The text says that “no housewife will need much propaganda to convince her that its labour-saving value in the domestic sphere is unchallengeable”, but goes on to talk about the financial value of the time saved in terms of home businesses such as poultry-rearing (which was traditionally a female enterprise) in addition to the main farm income. The two-colour illustration of ‘Electricity in the Home’ shows a neatly dressed woman looking towards a large two-storey farmhouse of the type found in better off areas around the country, with multiple chimneys as well as an connection from an overhead power line running outside the garden wall. This implies that the electricity had been retrofitted into an existing farmhouse, previously heated using fireplaces, although the appliances themselves are here left to the imagination. The double doors beside the main house could be to a garage, or more likely to a poultry shed, separating the smelly business of rearing poultry out from the daily work of domestic kitchen. Another view of presumably the same premises is shown in the ‘Electricity in the Farmyard’ image, where a suited pipe-smoking farmer surveys a tidy set of outbuildings and barns, which combine a horse cart, chickens and a water butt with an electric light and a set of pylons disappearing into the distance. Both of these depictions of exteriors include obvious signifiers of electricity like the pylons, poles and outdoor lights, but when they are combined with the highest quality farm settings, they provide an aspirational view into a world where electricity can elevate your home farm to the highest recognisable standards.

A wide set of appliances is shown on the cover of the pamphlet as line-drawn icons, alongside ‘Johnny Hotfoot’, a cartoon figure with a plug for a head that was used throughout ESB promotional literature of this period.15 Johnny is shown in a set of electricians’ overalls, ‘bursting’ out of the sheet of icons, and can be read as a personification of both the ESB and electricity itself, come to help the couple understand the economics behind upgrading their home and work (see Fig. 2). The appliances appear again in later pages of the pamphlet, with an individual breakdown of how long each one can be run for one unit of electricity. This includes two pages of ‘General Farm Uses’, one covering ‘Poultry & Egg Production’ and ‘Dairy’, another on ‘Water Pumping’. The page on ‘General Kitchen Use’ promotes the upgrading of appliances such as kettle, iron and the radio, as well as new appliances such as the electric cooker and vacuum cleaner (see Fig. 3). Each of these is showcased with a line-drawn icon, which recognisably include the upright Hoover vacuum cleaner, a GEC cooker and a round three legged washing machine, all of which were on sale through the ESB in the early 1950s. It explains the amount of work the appliance does for one unit, several of which are set up to emphasise the economic value of one unit of electricity, for example, boiling 18 pints of water or doing 4 weeks’ washing. The discussion emphasises cheapness and economy as much as it does speed and convenience, and this is emphasised by the spare monochrome drawings, which present the appliances with an economy of line.

The use of printed pamphlets as a marketing tool in the Irish context is an example of very culturally aware promotion tactics. In addition to public meetings, a fixture of Irish political life, the pamphlet has played an important role in disseminating official information to the Irish people.16 While the majority of the Irish population had left formal schooling at 14 and sometimes earlier, Irish culture retained a reverence for the written word that manifested itself in a public that read voraciously about public affairs, especially in the newspapers, ranging from national to local. The ESB themselves noted the success of their pamphlets in informing people about the rural electrification scheme, and initial black and white trials were expanded into two colours and distributed throughout the country.17

ESB television advertisements

By the mid-1960s, the improving economic situation in the Republic of Ireland and the rural electrification scheme meant that the majority of households in the State now had electricity. Many of the better off also availed of more exotic appliances and electrical goods, including the purchase of a television. While television signal had previously been confined to the east coast and Border areas where BBC could be picked up, the establishment of Radio Telefís Éireann (RTÉ) in 1960 meant that a home grown schedule of news and entertainment was now available across the country. By 1964, the ESB was also producing home-made television advertisements in order to stimulate demand amongst this growing demographic. Alongside advertisements entitled Electricity Helps in so Many Ways and Cleanest Cooking, A Penny Buys a Lot of Comfort was produced to continue the emphasis on the cost effectiveness of electricity in the home. The advertisement was bookended by a spinning Irish penny, which was designed in the 1920s to show a hen with a brood of chickens, intentionally associating the coin with women’s work in the house, both in terms of the raising of poultry and of the hen’s maternal instincts (see Fig. 4).18 It then works though a set of tasks that can be carried out using a penny’s worth of electricity, all of which are carried out by a fashionably dressed housewife with an adoring husband and four children (see Fig. 5). It ranges from a week’s washing and spin drying for ‘an average family’ to a running a fridge for an entire day, and illustrates this with the housewife moving clothes into a spin dryer with tongs and stocking up a fridge, etc. The continuing emphasis on cost effective labour appears in the form of ‘7 hours lighting’, which is illustrated by the housewife turning on a lamp to light her knitting. The fact that this advertisement is aimed at the better off consumer is highlighted by the presence of an electric blanket at the end of the advertisement, a more sophisticated, if not expensive product, which required a socket in the bedroom for operation.19 Again, the home and family represented would be familiar to Irish viewers, in terms of the gender roles where the woman does all the domestic work and the father is only seen at the breakfast table in his dressing gown. Also, the furnishings range from electrical appliances like the under counter refrigerator to familiar traditional objects such as the handmade quilted bedspread and blue and white striped Carrigaline ceramics. Again, this is presented to the viewer as an aspiration, and while it is not explicitly framed as ‘modern’, the modernist design of all the appliances shown and the continued emphasis on efficiency places it firmly on the ‘epochal’ end of the scale discussed earlier. The fact that electricity enables this ‘modern’ household to be run so efficiently positions it as an improving force in Irish society, one that will allow increased comfort within the home, but also one that allows traditional Catholic structures like large patriarchal families to flourish. This is a significant shift in the rhetoric surrounding electricity from both the early days of its promotion in Ireland, as well as how it was presented in several other European countries.20 It is particularly careful to position it as an ‘Irish’ aspiration in a recognisably Irish context, carefully blocking off any possible lingering post-colonial associations of ‘Britishness’.

The Irish Countrywomen’s Association

From a systemic point of view, the ESB were not the only organisation with a vested interest in promoting electricity to Irish users. Several voluntary organisations in the Irish countryside played such roles, but it is the Irish Countrywomen’s Association (ICA) that played the most notable, influential and sustained part in promoting electrical power amongst its many members. A very flatly-structured organisation, the ICA operated largely at the local guild level, although the early 1950s saw the purchase of An Grianán, a former ‘big house’ and hotel premises in County Louth, funded by a Marshall Aid grant from the Kellogg Foundation. This was used as a training centre for members, with residential courses ranging from week-long sessions focusing on a range of topics from arts and crafts and public speaking to running a B&B, as well as six-week domestic science course for teenage girls. The ICA’s mission was to improve the living conditions of its members and while it was avowedly ‘not feminist’ during this time period, the range and scope of its activities was an important force in improving both social and practical aspects of living in the Irish countryside.21 The ICA worked closely with the ESB in a number of ways, including the sponsorship of the six-week courses at An Grianán and the regular appearance of ESB demonstrators at ICA meetings, as well as a number of larger promotional projects, one of which will be considered here.

Back to topESB/ICA model kitchen at the 1957 Spring Show

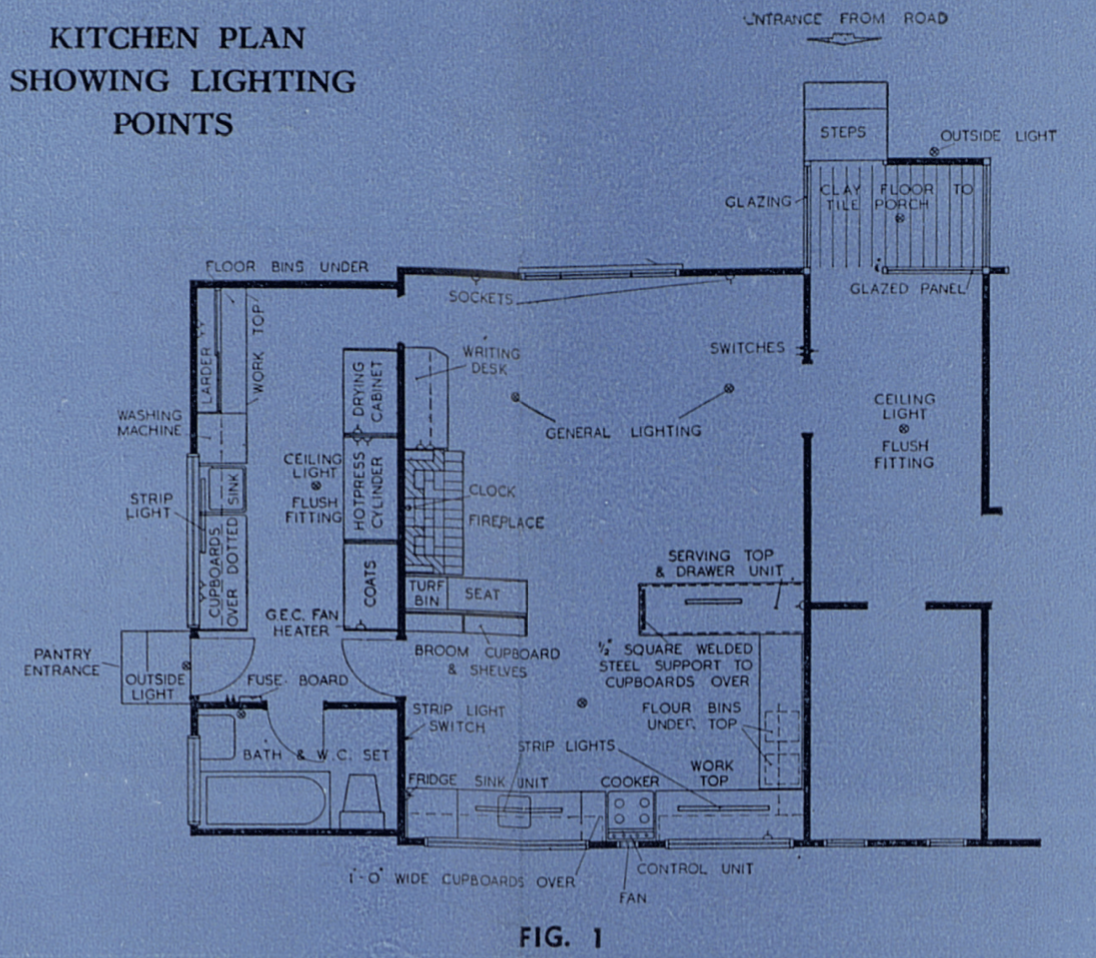

The ESB constructed a number of model electrical kitchens and houses during the 1950s and 1960s, the most popular of which was the ESB/ICA kitchen designed by architect and ICA Home Planning advisor Eleanor Butler in 1957, in conjunction with the Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland. This kitchen was initially displayed at the Royal Dublin Society Spring Show in May of that year, as part of the ESB’s regular yearly display, and it excited such interest from visitors to the agricultural show that subsequent versions were later installed into demonstration vans, which were driven around the country for several years.22 In addition, photographs of the kitchen display were used in an ESB pamphlet Modernising the Farm Kitchen, which clearly explained the layout and purpose of all the design decisions in the model kitchen (see Fig. 6).

The model kitchen took existing models of vernacular farm kitchens as its base model, with the plan divided into a sitting area near an open hearth, a dining area with a large farmhouse kitchen table and two ‘work’ areas for cooking and laundry (see Fig. 7). In a traditional farm kitchen, these functions would have been combined within one room, but the influence of modernist planning ideas mean that this kitchen was divided into open plan ‘zones’ divided by shelving or kitchen cabinets, if at all. Rather than the mostly portable furniture of the traditional Irish farm kitchen, the model kitchen is structured around built-in furniture such as kitchen cabinets and shelving, as well as a built-in version of a traditional wooden settle (high backed wooden seating, which often opened out to provide an extra bed).23 The cooking and laundry areas were surrounded by fashionable green and cream fitted cupboards under a Formica worktop, with both open and closed shelving and strip lighting overhead. One section of this shelving is notable for its intentional integration of traditional furniture forms, mimicking the traditional dresser format in proportions, and fulfilling the same role of display of ceramics on top and storage underneath. The open fire in the sitting room area was fitted with a back boiler, to provide hot water, as well as an early appearance of the infamous ‘immersion’ system for electrically heating hot water.24 The electrical ‘labour-saving devices’ were provided by the ESB and included an electric cooker, washing machine and rotary ironer, and the layout of the working areas was heavily influenced by Modernist developments in domestic kitchen design, particularly the concept of using a triangular layout to reduce the number of steps taken by the housewife during the course of the day.25

The model kitchen was written about in glowing terms in several Irish newspapers, including the Irish Press, which noted that ‘The old and new are beautifully combined with the traditional furnishings by the ICA and the electrical fitments by the ESB.”26 This combination of traditional and modern, or essentialist and epochal, is particularly noticeable in the sitting room area, where the wooden settle and armchair surround the open turf fire, watched over by a pair of Staffordshire dogs, but these recognisable components were complimented by the back boiler and a plugged-in radio, which could bring both RTÉ and Radio Luxembourg into the mix. Indeed, the inclusion of communications technology represented by the kitchen radio demonstrates that while the main focus in the model kitchen might be aspirations for more efficient ways of dealing with the mundane domestic tasks of cooking, washing and eating, there was less effort put into keeping the outside world at bay than in previous decades. The voracious reading habits of the Irish public are represented by the inclusion of a reading lamp for doing farm accounts or children’s homework, although this could also be used for the more feminised work of knitting, as in the television advertisement previously discussed. The media habits displayed here demonstrated on ongoing connection to the wider networks developed in Western Europe in the 19th century, where newspapers and radio combined with transport technologies such as the railway network to open the horizons of Europeans.

The model kitchen itself was part of a system of promotion, PR and advertising that was very much part of the same modernisation that had not avoided Ireland, contrary to some popular opinions.27 They were part of Ireland’s biggest agricultural show, which was held yearly in the extensive Dublin showgrounds of the Royal Dublin Society (RDS), and regularly attracted thousands of daily visitors, eager to survey the latest agricultural equipment and was described as an “invaluable shop window” that would “enable country people to keep in touch with the very latest developments in the rapidly changing pattern of rural life all over the world.”28 Model kitchens were intended to promote and inspire, by presenting to their main audience of Irish farm women a vision of a clean, modern efficient interior, which combined recognisable elements of their own domestic experience. This negotiation of epochal, modern electrical technology by the Irish housewife was framed in an unchallenging way that reinforced their existing lifestyles and thus gender roles, introducing elements of modernity surrounded by traditional signifiers and forms. As a result, this incremental approach was highly successful, with long queues at the Spring Show and the continuing popularity of the two mobile versions into 1961.29

Back to topElectricity and Religion: The Sacred Heart Lamp

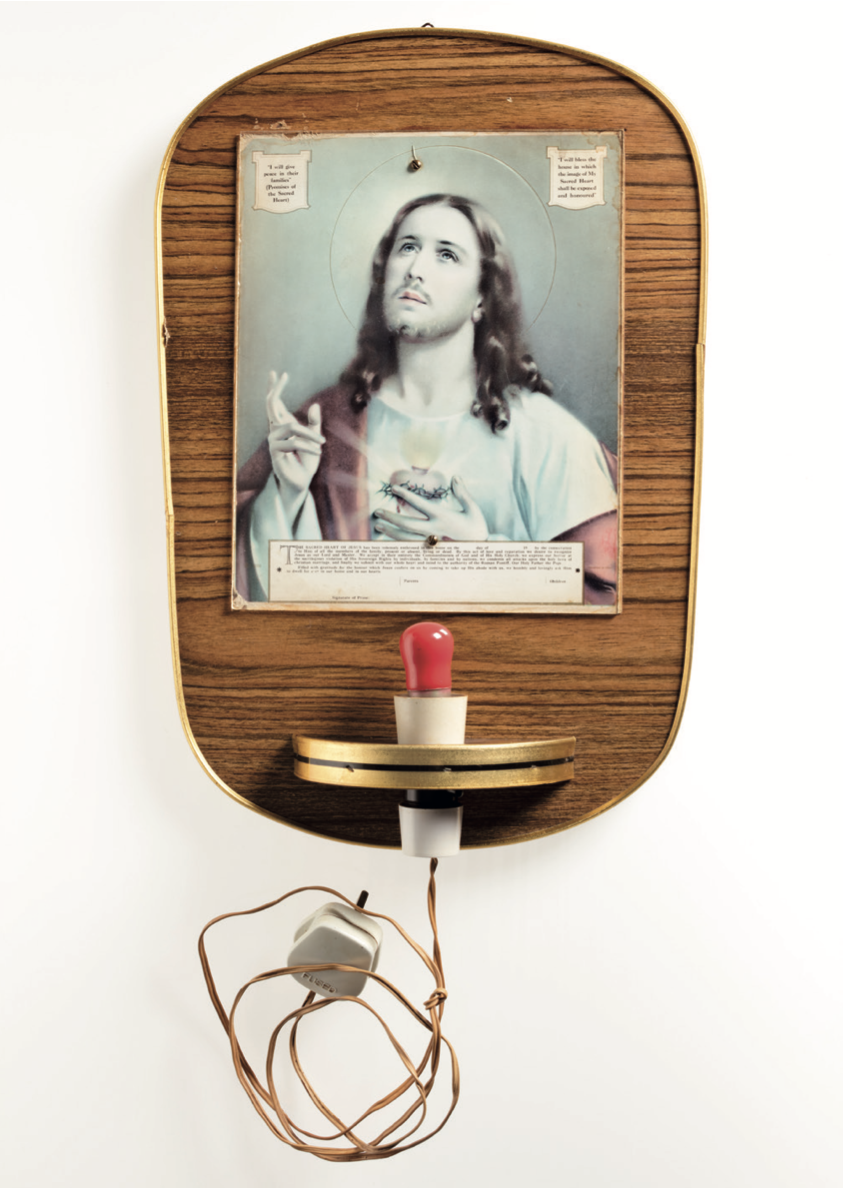

The integration of electricity into the daily life of Irish country people can be seen in the development of a particularly Irish type of object, that of the Sacred Heart lamp. This small domestic shrine dated back to the 19th century and consisted of a mass produced image of the Sacred Heart of Jesus above a perpetual oil lamp mounted in a red glass holder. While the image and oil lamp were mass produced objects, the exact configuration of the shrine differed from household to household, with some oil lamps mounted within an elaborate shrine, while others sat on a small shelf.30 These shrines were part of Ireland’s late 19th century devotional revolution, which involved intense and regular devotional rituals, centred around the Sacraments and figures such as Mary and the Sacred Heart of Jesus. This devotional revolution, which developed in the wake of Catholic Emancipation in the 1820s, had the effect of embedding Catholic religious practice into everyday life, rather than something furtive and outlawed as previously, and domestic shrines were decorated with constantly changing devotional displays, often of seasonal flowers, linen cloths and additional small statues and images. They were the focus of regular devotional practice within the household, particularly the daily recitation of the Rosary, and as such were carefully considered within the kitchen as a secondary focal point to the hearth. Devotion to the Sacred Heart dates back to 17th century France, but was popularised in the 1870s by the Archconfraternity of the Sacred Heart, was enthusiastically taken up in Ireland. Indeed, the entire nation was consecrated by the bishopric to the Sacred Heart in 1873, and promoted by Fr. James Cullen SJ in the 1880s. Fr. Cullen was also the founder of the Pioneer Total Abstinence Association, which campaigned against alcoholism and whose members took a pledge of total abstinence, as well as the founder of the Irish Messenger of the Sacred Heart, a monthly religious magazine, which is still in circulation. This use of modern communication methods worked in conjunction with the much older confraternity organisation to promote the specific rituals and devotions of the Sacred Heart within Ireland, making the Sacred Heart lamp a very common sight in Catholic domestic interiors. It was often given to a newly wedded couple, and the initial ‘enthronement’ ceremony dedicated the household to the Sacred Heart and situated it as the spiritual head of the household. It positioned the spiritual and moral authority of Jesus and by implication, the Catholic hierarchy, above that of the default ‘father’ of the household, who normally held the vast majority of the decision-making power within the household, certainly legally and socially, if not always practically, given that actually running the household was considered to be woman’s work.31

Back to topThe Electrification of the Sacred Heart

The coming of electricity to rural Ireland meant that the Sacred Heart lamp was included in the modernisation of the domestic interior. The devotion to the Sacred Heart continued throughout the 1950s and 1960s, only starting to wane after the liberalisation of Catholic teaching in the wake of the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council in the early 1960s. The wave of houses being upgraded throughout the country from the early 1950s onwards included the Sacred Heart lamp as just another element of the kitchen to be upgraded, albeit with more reverence than an iron or kettle. They do somewhat fly under the radar in the official literature - the ESB, as a secular organisation, did not sell or promote the upgrading of the lamps, and the only mention of them in their official publications is a quote from an enthusiastic housewife, Mrs. Nellie Long of Cahirfelane in County Kerry (see Fig. 8) who had wired her house in advance of electricity supply arriving in her area: “You might mention we think poorly of not getting the electricity and the Lord feels the same as we wired the Sacred Heart lamp at the same time.”32 This attribution of enthusiastic divine support for rural electrification was mostly echoed by the clergy themselves, with much practical support supplied at a local level. This support was mostly implicit, rather than overt preaching or speeches, and ranged from the use of parish and school halls for electrical demonstrations to turning a blind eye to church gate canvassing. The main endorsement of rural electrification, however, came through the official ‘switching-on’ ceremony conducted in each of the 756 areas in the state as they were slowly completed. This ceremony, again usually in a parish or school hall, was generally officiated over by a triumvirate of male officials, usually the highest ranking officials available from the ESB, local or national politics and the Catholic hierarchy. For more remote areas, this may have been an engineer, a local councillor and the parish priest, but for the switching-on of the 100,000th rural consumer at Ballinamult Creamery in County Waterford, the parish priest Fr. Walsh was considered sufficiently high status to share a stage with Seán Lemass, then Minister for Industry and Commerce, and R.F. Browne, the Chairman of the ESB.33

The majority of electrical Sacred Heart altars did not differ greatly from their oil predecessors in many ways. The red glass oil holder was replaced by a small angled light socket, which was often wired directly into the mains. A specially shaped tall red light bulb was then inserted, which had an electrical filament formed into the shape of a cross, as an additional sign of devotion. This was often installed over an existing shelf used as an altar, so that the seasonal range of additional devotional elements could be continued. Sometimes, however, the Sacred Heart picture and the lighting element were left alone on the wall, especially if other ‘holy pictures’ were also hung – these could range from images of the Blessed Virgin and the Pope to rather more secular images of Irish-American President John F. Kennedy. The importance of the Sacred Heart lamp at a social and cultural level could be seen in its inclusion in the basic electrification set-up, alongside one light in each room and a single socket in the kitchen. Hannah Mai Allman points out the importance of this practice to her family and particularly her grandmother, who would have been born at the height of the devotional revolution in the late 19th century:

HA: That’s all, they were only putting the one plug and the Sacred Heart Lamp (laughs).

EC: Did they have the Sacred Heart Lamp back then?

HA: How did they get the Sacred Heart Lamp… now they would come with, that would be the first things back then that they were looking for.

EC: Yes?

HA: And my grandmother said, “Oh, I would love to see the Sacred Heart” and sure, she was dead before she saw it.34

This interview reinforces the broader respectful attitude towards the practice as a centrally important part of wiring the home, but it also foregrounds the wistful longing of Hannah Mai’s grandmother, emphasising the emotional importance of the Sacred Heart lamp to this older generation in particular.

The Sacred Heart altars continued to take a wide range of forms, albeit with new concerns about the electrical safety of such installations. The ESB were only responsible for providing an electrical connection to the junction box in the house, usually just inside the back door, and the actual internal wiring of houses was done by local contractors, with varying degrees of expertise, skill or qualifications. The devotional imperative to keep the Sacred Heart lamp burning in perpetuity meant that is was common practice to wire it directly into the mains, rather than provide a switch, and both this and the possible flammability of the surrounding arrangements caused some concern, as Rosemary Connolly explains:

RC: A little oil lamp, so, we all got these electric ones when the electricity came and we, our neighbour had had TB [tuberculosis] some years before and he had been in Peamount [Sanitorium] and he had made my mother a beautiful fretwork it was called, it was a fine wood and you cut it out with the little jigsaw and it was little crosses and the picture of the Sacred Heart in it and the man who wired the house had brought around the new-fangled Sacred Heart light and had it attached to it and the man came that day to switch it on, he said he wasn’t too sure about the safety of this, but seeing it was up on the wall and that we wouldn’t be touching it, but he warned my mother when she’d be painting or cleaning it or anything to make sure and stick out the fuse out of it.35

This quote provides an insight into a cross section of mid-century Irish society – in addition to Rosemary’s mother’s religious devotion and the safety concerns of the electrical installer, it also highlights the pre-antibiotic prevalence of tuberculosis in 1950s Ireland, where the main recourse for patients was isolation, fresh air and rest in a purpose built sanatorium. These patients were encouraged to take up light hobbies as a psychological support during treatment and a non-taxing way of supporting themselves upon discharge, and the small scale woodwork involved in making a fretwork altar with a jigsaw fits easily into this category of work. It also meant that the obviously mass produced light bulb and the printed devotional image were surrounded and enclosed by hand crafted Irish work, which fit ideologically with the association of Irishness with the handmade, as well as the concept of devotion through physical labour.36

A later example of a Sacred Heart lamp takes a different, rather more modern approach to combining electrical light with devotional practice (see Fig. 9). The print of the Sacred Heart is mounted onto a wood-grain effect laminate backboard, above a small semi-circular shelf which the light fitting is mounted into. The print is covered with a sheet of transparent plastic (although this has not prevented the subsequent fading of the colours) and the combination of both picture and light on the one board ensures that they stay in the same relationship with each other, regardless of where the assemblage is hung. The horizontal wood grain pattern is printed onto the backboard and both backboard and shelf are edged with gold and black edging, not dissimilar to the edging used to protect 1950s café tables from wear. There is no manufacturers mark or stamp included anywhere on the assemblage, but the three examples found are all from houses around the Portlaoise area, making it likely that these were small scale local manufactures, possibly of a similar scale to the efforts of Peamount Sanatorium. This example, however, demonstrates a use of ‘modern’ materials and shape, with laminate and gold-coloured edging as well as the use of lines and arcs to create both the shape of the backboard and shelf. This lamp is also rather different from the usual assemblage in that it has survived with a plug at the end of the cabling, which indicates that it may have been sold as a commercial product, rather than assembled on a craft making basis or in the home itself.

Conclusion

The role played by rural electrification in mid-century Ireland was influenced partly by the existing technical and organisational infrastructure of the post-colonial state, but also by the cultural specificities of that state. The poor economic performance of the 1950s, prior to the introduction of free market policies, and the lack of education amongst the population meant that widespread electrification was treated with some trepidation in many rural areas. The lack of understanding and shortage of money were both hurdles that were surmounted by the ESB in their attempts to covert as much of the population as possible to this new technology. The ESB focus on routes for promoting electricity such as pamphlets and model kitchens meant that they could extoll the virtues of this power source in a multiplicity of ways – written, visual and physical. This multi-modal approach meant that the Spring Show model kitchen was a fully immersive physical experience, but one restricted to the better-off farmer couple who could afford to visit Dublin and pay to attend the Spring Show. However, this experience was photographed and written about in the national and local newspapers, as well as forming the basis of a subsequent ESB pamphlet, moving the persuasion into visual and textual form.

The overt combination of tradition and modernity in this model kitchen is typical of the ESB approach in this period, especially when working in conjunction with the women’s organisation of the ICA. The combination of both forces in the kitchen, through the guidance of Eleanor Butler, meant that it managed to present electrical appliances and lighting to quite a conservative audience in a way that did not startle or shock them. On the other hand, she managed to achieve a balance between epochalism and essentialism that could be easily presented as a new and exciting version of a traditional kitchen, combining modernist zoning, appliances and materials with traditional colour schemes and furniture.

Outside of the official promotion and narrative of the ESB, we see this mixing of tradition and modernity continuing with the widespread electrification of the domestic Sacred Heart lamp. The existing mass produced devotional prints were joined by mass produced light bulbs and fittings, but continued to be presented within the handmade and small batch production economy of the Irish countryside, particularly that of the products of charity workshops. This represented a very successful integration of electricity into an existing cultural narrative, managing to strip it of its associations of Britishness and urbanity and make it into something Irish and local. This is the advantages of a design historical approach when considering electricity, not just as an abstract force, but as one that made real physical changes to the landscape, workplace and home. It is through the negotiation of physical objects and space that we can see how electricity was intended to change people’s lifestyles and some of the humble, everyday ways in which it actually did.

The rural electrification project in Ireland represents a significant energy transition for most of the population, moving from the exclusive burning of fossil fuels in situ to the installation of infrastructural power into the home. While this electrical power was partly generated by water and partly by fossil fuel, and sustainability was not yet a consideration, it is important to consider the objects of the past and their meanings, and what they can tell us about how such a transition might work at a domestic level. In this case, the desire to ‘be modern’ ultimately outweighed the comfort of familiar tradition, especially when the familiar involved a good deal of manual labour. The oral histories complement the design historical object analysis to tease out emotions and attitudes on the ground, which demonstrate that this enthusiasm for domestic electrical technology was not just present in the official narrative. However, a move away from official, written narrative gives space for insights into the importance of cultural and social specificity when considering such an energy transition and the changes it brings.

- 1. Mary O’Mahoney, “Interview,” interview by Sorcha O’Brien, Electric Irish Homes, November 20th, 2017.

- 2. Sorcha O’Brien, Powering the Nation: Images of the Shannon Scheme and Electricity in Ireland (Newbridge: Irish Academic Press, 2017).

- 3. Siegfried Giedion, Mechanization Takes Command: A Contribution to Anonymous History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1948).

- 4. Grace Lees-Maffei, “The Production–Consumption–Mediation Paradigm,” Journal of Design History 22, no. 4 (2009): 351-76.

- 5. Sarah A Lichtman and Jilly Traganou, “Introduction to Material Displacements,” Journal of Design History 34, no. 3 (2021): 195-211.

- 6. Michael Billig, Banal Nationalism (London: SAGE Publications, 1995).

- 7. Clifford Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures, 2nd ed. (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2000); Paul Caffrey, “Ireland, Design and Visual Culture: Negotiating Modernity 1922-1992,” ed. Linda King and Elaine Sisson (Cork: Cork University Press, 2011); O’Brien, Powering the Nation.

- 8. Grace Lees-Maffei, Design at Home: Domestic Advice Books in Britain and the USA since 1945 (Abingdon: Routledge, 2013); Caitriona Clear, Women’s Voices in Ireland: Women’s Magazines in the 1950s and 1960s (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016).

- 9. Joanna Bornat and Hanna Diamond, “Women’s History and Oral History: developments and debates,” Women's History Review 16, no. 1 (2007): 19-39; Robert Perks, The Oral History Reader, 3rd ed. (London: Routledge, 2015).

- 10. Maurice Manning and Moore McDowell, Electricity Supply in Ireland: The History of the E.S.B. (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 1984); Michael Shiel, The Quiet Revolution: The Electrification of Rural Ireland (Dublin: The O’Brien Press, 1984).

- 11. Diarmuid Ferriter, The Transformation of Modern Ireland 1900-2000 (London: Profile Books, 2004); Terence Brown, Ireland: A Social and Cultural History 1922-2002, 2nd ed. (London: Harper Perennial, 2004); Tom Garvin, Preventing the Future: Why Was Ireland So Poor For So Long? (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 2004).

- 12. O’Brien, Powering the Nation.

- 13. Bunreacht na hÉireann: Constitution of Ireland, (Dublin: The Stationary Office, 2015), 41.2. This article is still in force today, as moves to remove it or make it gender neutral were halted by the Covid-19 pandemic. At the time of writing a referendum on the subject has been announced for November 2023.

- 14. “Pamphlet library: 1940s-60s,” 2021, accessed January 9, 2021, https://esbarchives.ie/rural-electrification-pamphlets/.

- 15. “A Camera and a Question,” Prospect, 1966, 8.

- 16. Nina Holmes, “A Picture of Health: Visual Representation of the Subject in Irish Government Health Ephemera, 1970 –1996” (PhD Kingston University, 2017).

- 17. “Kitchen Planning,” REO News, 1957, 3.

- 18. Caffrey, “Ireland, Design and Visual Culture: Negotiating Modernity 1922-1992,” 74-89.

- 19. “A Camera and a Question,” 21.

- 20. O’Brien, Powering the Nation.

- 21. Aileen Heverin, ICA: The Irish Countrywomen’s Association A History 1910-2000 (Dublin: Wolfhound Press, 2000); Diarmuid Ferriter, Mothers, Maidens and Myths: A History of the Irish Countrywomen’s Association (Dublin: FÁS, 1995).

- 22. “Kitchen Planning,” 4.

- 23. Claudia Kinmonth, Irish Country Furniture and Furnishings 1700-2000 (Cork: Cork University Press, 2020), 150-66.

- 24. Irish immersion systems were retrofitted into many houses in this time period, and continue to be installed in new builds into the 21st century. Their notoriety stems from their high cost when heating water electrically, necessitating eagle eyed watchfulness to prevent extremely high electricity bills if left on overnight, etc.

- 25. “Electricity in Farmhouse and Farmyard: ESB Exhibit for Spring Show,” Irish Examiner, May 3 1957; “Electricity on the Farm and in the Kitchen: An Eye Opener at Ballsbridge: ESB Exhibit at the Show,” Meath Chronicle, May 4 1957, 6.

- 26. “Around the Show,” Irish Press, May 8 1957, 3.

- 27. Éamon De Valera, On Language & the Irish Nation (Raidió Éireann, 1943).

- 28. “The Spring Show,” Irish Press, May 8 1957, 8.

- 29. “Dublin Spring Show,” Irish Examiner, May 10 1957, 10; Electricity Supply Board, Thirty-Fourth Annual Report of the Electricity Supply Board Ireland for the Year Ended March 31st 1961, 11 (Dublin: Electricity Supply Board, 1961); Electricity Supply Board, Thirty-First Annual Report of the Electricity Supply Board Ireland for the Year Ended March 31st 1958, 18 (Dublin: Electricity Supply Board, 1958).

- 30. Kinmonth, Irish Country Furniture and Furnishings 1700-2000, 409-15.

- 31. “One Hundred and Thirty Years of the Sacred Heart Messenger,” Ireland’s Own, February 2, 2018, 4-8.

- 32. “A Camera and a Question,” 11.

- 33. “The 100,000th Consumer,” REO News, 1954, 12.

- 34. Hannah Mai Allman, “Interview,” interview by Eleanor Calnan, Electric Irish Homes, April 11th, 2018.

- 35. Rosemary Connolly, “Interview,” interview by Geraldine O’Connor, Electric Irish Homes, February 22nd, 2017.

- 36. Alan McCarthy, “The treatment of tuberculosis in Ireland from the 1890s to the 1970s: A case study of medical care in Leinster” (PhD Maynooth University, 2015), 296.

“The 100,000th Consumer.” REO News, 1954, 12-14.

Allman, Hannah Mai, “Interview,” interview by Eleanor Calnan, Electric Irish Homes, April 11th, 2018.

Allman, Hannah Mai, “Pamphlet Library: 1940s-60s.” 2021, accessed January 9, 2021, https://esbarchives.ie/rural-electrification-pamphlets/.

Allman, Hannah Mai, “Around the Show.” Irish Press, May 8 1957, 3.

Billig, Michael, Banal Nationalism (London: SAGE Publications, 1995).

Bornat, Joanna, and Hanna Diamond, “Women’s History and Oral History: Developments and Debates.” Women’s History Review 16, no. 1 (2007): 19-39.

Brown, Terence, Ireland: A Social and Cultural History 1922-2002, 2nd ed. (London: Harper Perennial, 2004).

Bunreacht Na hÉireann: Constitution of Ireland, (Dublin: The Stationary Office, 2015).

Caffrey, Paul, “Ireland, Design and Visual Culture: Negotiating Modernity 1922-1992,” ed. Linda King and Elaine Sisson, Ireland, Design and Visual Culture: Negotiating Modernity 1922-1992 (Cork: Cork University Press, 2011).

Allman, Hannah Mai, “A Camera and a Question.” Prospect, 1966, 10-11.

Clear, Caitriona, Women’s Voices in Ireland: Women’s Magazines in the 1950s and 1960s (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016).

Connolly, Rosemary, “Interview,” interview by Geraldine O’Connor, Electric Irish Homes, February 22nd, 2017.

Crosby, Edward, “The Stations.” The Furrow 20, no. 8 (August 1969): 408-10.

De Valera, Éamon, On Language & the Irish Nation. Raidió Éireann, 1943.

De Valera, Éamon, “Dublin Spring Show.” Irish Examiner, May 10 1957.

De Valera, Éamon, “Electricity in Farmhouse and Farmyard: ESB Exhibit for Spring Show.” Irish Examiner, May 3 1957, 6.

De Valera, Éamon, “Electricity on the Farm and in the Kitchen: An Eye Opener at Ballsbridge: ESB Exhibit at the Show.” Meath Chronicle, May 4 1957, 6.

Electricity Supply Board, Thirty-First Annual Report of the Electricity Supply Board Ireland for the Year Ended March 31st 1958. (Dublin: Electricity Supply Board, 1958).

Electricity Supply Board, Thirty-Fourth Annual Report of the Electricity Supply Board Ireland for the Year Ended March 31st 1961. (Dublin: Electricity Supply Board, 1961).

Ferriter, Diarmuid, Mothers, Maidens and Myths: A History of the Irish Countrywomen’s Association (Dublin: FÁS, 1995).

Ferriter, Diarmuid, The Transformation of Modern Ireland 1900-2000 (London: Profile Books, 2004).

Garvin, Tom, Preventing the Future: Why Was Ireland So Poor for So Long? (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 2004).

Geertz, Clifford, The Interpretation of Cultures, 2nd ed. (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2000).

Giedion, Siegfried, Mechanization Takes Command: A Contribution to Anonymous History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1948).

Heverin, Aileen, ICA: The Irish Countrywomen’s Association a History 1910-2000 (Dublin: Wolfhound Press, 2000).

Holmes, Nina, “A Picture of Health: Visual Representation of the Subject in Irish Government Health Ephemera, 1970 –1996” (PhD Kingston University, 2017).

Kinmonth, Claudia, Irish Country Furniture and Furnishings 1700-2000 (Cork: Cork University Press, 2020).

Kinmonth, Claudia, “Kitchen Planning.” REO News, 1957, 4.

Lees-Maffei, Grace, Design at Home: Domestic Advice Books in Britain and the USA since 1945 (Abingdon: Routledge, 2013).

Lees-Maffei, Grace, “The Production–Consumption–Mediation Paradigm.” Journal of Design History 22, no. 4 (2009): 351-76.

Lichtman, Sarah A, and Jilly Traganou, “Introduction to Material Displacements.” Journal of Design History 34, no. 3 (2021): 195-211.

Manning, Maurice, and Moore McDowell, Electricity Supply in Ireland: The History of the E.S.B. (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 1984).

McCarthy, Alan, “The Treatment of Tuberculosis in Ireland from the 1890s to the 1970s: A Case Study of Medical Care in Leinster” (PhD Maynooth University, 2015).

O’Brien, Sorcha, Powering the Nation: Images of the Shannon Scheme and Electricity in Ireland (Newbridge: Irish Academic Press, 2017).

O’Mahoney, Mary, “Interview,” interview by Sorcha O’Brien, Electric Irish Homes, November 20th, 2017.

O’Mahoney, Mary, “One Hundred and Thirty Years of the Sacred Heart Messenger.” Ireland’s Own, February 2, 2018, 4-8.

Perks, Robert, The Oral History Reader, 3rd ed. (London: Routledge, 2015).

Shiel, Michael, The Quiet Revolution: The Electrification of Rural Ireland (Dublin: The O’Brien Press, 1984).

Shiel, Michael, “The Spring Show.” Irish Press, May 8 1957, 8.