The regulation and expansion of the gas industry in nineteenth-century France and Spain: a comparative approach

Université de Malaga

maria.vazquez[at]uma.es

English Translation of "La réglementation et l’expansion de l’industrie du gaz en France et en Espagne au 19e siècle: une approche comparative" by Arby Gharibian.

This paper presents the evolution of the regulation of the gas industry in France and Spain during the 19th century. To this end, numerous studies on gas management have been analysed and the evolutionary process of this public service has been examined from a legislative and organisational point of view. This provides an approach to the development of this sector, which in both countries was based on the concession model, where private companies managed the gas lighting service, led by both foreign and national entrepreneurs.

Introduction

A process of implementing new public services unfolded throughout the nineteenth century in Europe, where the construction of large-scale urban infrastructure had a major impact from an economic, political, social, legislative, technological, and commercial point of view. In particular, the development of the European gas industry beginning in the mid-nineteenth century led to the emergence of a complex legislative and economic framework that completely transformed national and international markets. As a result, questions such as the development of the gas industry, urban infrastructure, the regulation of concessions, and conflicts between private enterprises and local authorities have drawn the attention of historians and economists in recent years.

The process of the European gas industry’s regulation and organization has been especially important, and it is therefore interesting to reflect on the different regulation mechanisms that emerged between the nineteenth and twentieth century, as well as conflicts between public and private actors.

More specifically, the management of public gas services differed significantly depending on the European setting, with two primary regulation models or mechanisms standing out: countries such as Great Britain, Germany, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden opted for a direct management model for the service, while countries such as France, Spain, Italy, and Portugal developed a policy of concessions in most of their municipalities.

This article will study the concession model used in France and how it was implemented in Spain, analyzing the primary similarities and differences between the two countries.

In addition, the gas industry brought up to date certain economic and legal aspects from the Ancien Régime, such as the mercantilist practice of exclusive privilege. To promote certain types of economic activity, the state granted exclusive privileges for a fixed duration ranging between 15 and 50 years. This privilege was assumed by gas companies in order to avoid any competition, thereby creating a monopoly. During the nineteenth century, the administrative concession subsequently served as an updated version of this longstanding prerogative. In this respect, the legacy of the Napoleonic Code applied not only in France, but also in countries such as Portugal and Spain, whose legislation was inspired by French regulation1.

This study will firstly analyze the development of gas lighting in France, along with its regulation and evolution throughout the nineteenth century. It will then focus on the process pursued in Spain, with a view to explaining how the gas industry was established and developed based on a model similar to that of France, before analyzing the dominant role played by private companies, as well as the successive legislative reforms pursued by the state to regulate the service. A few closing considerations are also included by way of conclusion.

Back to topGas lighting in France: development and regulation

The beginnings of gas lighting in France date back to the late eighteenth century, when the engineer Philippe Lebon (1767-1804) patented the first gas lamp in 1799. Lebon was pursuing major gas lighting projects when he was murdered in Paris in December 1804. His death momentarily stopped the development of this sector in France. In 1802, the first gas company was created in Paris under the name Compagnie Parisienne de l’Éclairage et du Chauffage par le Gaz, which a few years later secured a monopoly to supply gas to Paris, which was later extended to include other French cities. Similarly, in 1812 M. de Chabrol, the prefect for the Seine department, included gas in the works he launched to light l’hôpital Saint-Louis. Five years later, in 1817, Fréderick Albert Winsor (1763-1830) founded the Société des Intéresses pour l’Éclairage au Gaz to provide this public lighting service in Paris, but had to dissolve the company in 1819 due to a lack of profitability2.

This is when the true expansion of the gas industry occurred in France, in the 1820s and 1830s, when gas began to be widely used to light streets and homes across the country3. Gas was produced from coal, wood, and other fuels, which required major infrastructure for its distribution via gas pipelines. As gas technology developed, new plants were built in France to provide gas to households and companies. The expansion of this service made France the most advanced country in Latin Europe in terms of the introduction and diffusion of gas4. From the mid-nineteenth century onward, France began to export its gas knowledge to other parts of Europe, from both a financial and technical standpoint. French engineers played an essential role in introducing the technology in Europe, especially in countries around the Mediterranean Basin5.

With respect to the development of the gas industry in France, the Compagnie Française was created in 1820 to supply the French capital with public gas lighting, and the Compagnie Royale d’Éclairage was created in Paris in 1824. During the ensuing years, in order to avoid clashes with the various gas supply companies that emerged, the Paris city council identified zones or sectors of the city in which each company could operate6. The expansion continued during the 1830s, as two new commercial entities were created in 1834–the Compagnie de Belleville and the Compagnie Lacarrière–followed by the Compagnie Parisienne in 1836, and the Compagnie de l’Ouest in 18397.

The role of foreign entrepreneurs, especially from England, was especially important in this expansion. After Winsor and his Société des Intéresses pour l’Éclairage au Gaz between 1817 and 1819, Aaron Manby of England, Jean Henry of France, and Daniel Wilson of Ireland filed a patent for the production of gas on May 12, 18218 In August of the same year, they founded what is colloquially known as the Compagnie Anglaise, whose official name was Manby, Henry, Wilson et Cie9. In August 1827, Jean Henry ended his relations with the company, which in 1832 took the name Manby, Wilson et Cie. In 1834 the company took over the Compagnie Royale—created by Louis XVIII in 1819—and was privatized in 1822 under the name Société pour l’exploitation de l’Usine Royale d’Éclairage10. The death of Daniel Wilson, who had led the company since 1827, resulting in a change of owner in 1849, when Aaron Manby appointed Louis Margueritte as the new director, with the company being renamed Manby, Margueritte et Cie. One year later, after Manby’s death, Margueritte became the company’s sole director. The company took the name Louis Margueritte et Cie. on January 13, 1854, and had two gas plants in the French capital11.

However, British influence over the spread of the gas industry in France lessened as the nineteenth century advanced. The earliest proposals were connected to English engineers and entrepreneurs, until the diffusion of technology allowed local entrepreneurs, as well as those from other countries, to bid for concessions for public gas lighting12.

With respect to regulation and gas-related standards, the first technical safety standards in France appeared in the context of a major social conflict. In the early 1820s, gas lighting sparked intense complaints and protests in Paris, with the inhabitants of some posh neighborhoods initiating a fight against entrepreneurs out of fear of exploding gas meters, and the resulting danger for their safety13.

In addition, in March 1822, following a series of explosions in the United States and Great Britain that were reported in the Parisian press, the Minister of the Interior, Corbière, banned high-pressure water heaters within 70 meters of dwellings. In practice, this amounted to banning their use in cities. The Conseil de Salubrité (Health Council) refused to apply the decision. Difficult months followed, with a number of attacks and disagreements between entrepreneurs and various authorities, until October 1823, when an order imposed the use of new safety measures14.

It was therefore the fear of gas plants on the part of citizens, who considered this activity dangerous–as well as the need to improve safety mechanisms–that led to their regulation.

On August 20, 1824, a Royal Order was published, which did not limit the size of gas tanks but indicated that establishments connected to gas lighting, which is to say plants and depots, were included in Category 2 of dangerous, unhealthy, and inconvenient establishments, as established by the decree of October 15, 1810 (they could therefore be built amid homes). This provision stipulated that such establishments had to adhere to the safety measures announced in the Instruction published on August 30, 1824, all while being subject to constant and minutious monitoring on the part of local authorities15.

Concretely, the primary safety measures approved by the Royal Order of August 24, 1824 were the following:

- Gas tanks had to be built outside or in well-ventilated storage buildings.

- Gas tanks and their storage buildings had to be built using inflammable materials.

- The storage buildings for gas tanks had to be kept at a distance from the installation, and also equipped with a lightning rod.

- The tanks had to be dug into the ground to prevent them from bursting from water pressure.

- The gas tank’s manhole and storage building had to be locked, with the owner keeping the key.

- A safety pipe would be installed in the event of fire or excessive filling of the tank.

- No maximum capacity was established for gas tanks16.

The Instruction from August 30, 1824 had four chapters: the first listed the conditions that had to be met to establish a gas plant; the second indicated the conditions that had to be met in order for the condensation of volatile products and gas refining not to harm the surrounding area; the third showed the conditions that had to be met to prevent danger during the operation of gas tanks; and the fourth discussed the conditions imposed on producers who compressed gas for transportation in mobile tanks17.

In the ensuing years, rules continued to be adopted to regulate the sector, as well as the problems it raised. By the Royal Order of July 26, 1826, the government prescribed that unhealthy industries not be concentrated in a single location, in order to evenly distribute nuisances across all neighborhoods. However, the Conseil de Salubrité defended the idea of relegating unhealthy plants to a single site by creating industrial groupings or concentrations to ensure monitoring and safety18.

Two years later, via the Royal Order of September 1828, gas extraction plants were included in Category 1 of dangerous, unhealthy, and inconvenient establishments. The Royal Order of March 25, 1838 extended monitoring of the gas industry by the local police to gas tanks with a capacity over seven cubic meters, as well as to small domestic gas lighting equipment. The Royal Order of January 27, 1846 once again modified the regulation of the gas industry and gas equipment19.

Of the laws adopted during those years, the Royal Order of December 26, 1846 on the sale of gas in Paris bears mentioning. It consisted of five provisions. The first regulated the nature of gas, as well as the supply network of the companies to which the concession was granted for 17 years–from January 1, 1847 to December 31, 1863–by indicating the scope of the network and the conditions of supply. The second discussed the conditions for subscribers, which is to say it determined the duration of the contract (minimum three months), and how to proceed with a sale (via a meter or by the hour). The third involved meters, which had to be approved by the administration, and whose cost has to be paid by the service user. The fourth established the rates charged by concessionary companies. In 1847, the price for a cubic meter sold via a meter was 49 cents, which would be reduced annually by one cent until reaching the price of 40 cents in 1856. This price was maintained until the end of the concession in 1863. Finally, the fifth provision indicated the tribunals in charge of resolving incidents arising from these regulations20.

This regulation of the gas lighting market in Paris reduced the profitability of the six companies operating in the French capital at the time: Compagnie Française, Compagnie L. Margueritte, Compagnie de Belleville, Compagnie Lacarrière, Compagnie Parisienne, and Compagnie de l’Ouest. In 1850 they all agreed, along with the city council, to create a scientific commission to study the most equitable operating model for public lighting for both the city and companies. After five years of studies, the commission proposed unifying the gas companies of Paris into a 50-year concession21.

The merger of all of these gas distribution companies in Paris led to the creation of the Compagnie Parisienne d’Éclairage et de Chauffage par le Gaz, which took over the concession for supplying gas to the French capital until 1905. The treaty of the concession signed on July 19, 1855 between the City of Paris and the Compagnie Parisienne d’Éclairage et de Chauffage par le Gaz remained practically unchanged during the 50 years of its application, despite frequent disagreements between the City of Paris and the concessionary company. The concession treaty contained three essential clauses:

- At the end of the concession, the City of Paris would become the owner of the pipes, with no compensation for the concessionary.

- The city would share in the company’s profits.

- The concessionary would systematically integrate “scientific progress” in its practice, in order to provide the best economic performance and lowest sale price22.

The Scientific Progress Clause was included in concession contracts to avoid the abusive practices of gas companies. The clause sought to obligate companies to implement technological innovations over time, otherwise municipalities could assume control of the service and entrust it to a new company23.

The expansion of the gas industry in France during the second half of the nineteenth century is reflected in the increase of annual gas emissions in Paris between 1856 and 1907. Parisian consumption rose over these years, growing from 43,693,593 m3 to 389,659,179 m3 in the space of 50 years (Figure 1).

Source: personal compilation based on CCSC Genealogy Branch. Hauts-de-Seine Branch of the CMCAS club of Electric and Gas Industries, “Tableau d’Honneur des Électriciens et Gaziers - 1914-1918”, 2004. Url: http://ccsc.

genealogie.free.fr/TH/societes-SGP.htm (accessed 10/04/2023).

The industry expanded rapidly in the rest of France, reproducing the capital’s concessionary model. In 1825, the cities of Bordeaux and Lille already had their own gas plants, managed in both cases by the British company Imperial Continental Gas Association24.

For Bordeaux, the Royal Order of June 23, 1824 authorized the creation of a société anonyme (corporation) named Compagnie d’éclairage de la ville de Bordeaux par le gaz hydrogéne to supply the city with gas lighting for 30 years, with the local merchant Jean Benel serving as director25. The following year, via the municipal order of October 25, 1825, the company was authorized to install gas pipes in a number of streets. The plant was located in the Caudéran neighborhood and initially supplied only individuals, but the city became interested in this type of lighting, and signed a contract with the company on September 11, 1829 to provide gas lighting for Place Louis XVI and Place Louis-Philippe I, today the Place des Quinconces. The lighting began to operate in October 1830, and the service was extended in July 1832 with the signing of a new contract with Benel to light the Allées de Tourny26.

In 1836, the city council established specifications for extending lighting to other parts of the city, which were modified in 1838 and approved by the council on September 21 of the same year. The concession was granted on August 28, 1839 to the Imperial Continental Gas Association for a period of one year beginning on January 1, 1842. The company renegotiated the concession’s conditions on a number of occasions, and was able to maintain it until December 31, 1875, the date of creation for the Companie du Gaz de Bordeaux, which has provided the service ever since.27

The Imperial Continental Gas Association also began to light the city of Lille in 1825 by building a gas plant in the Saint-André neighborhood, whose director was N. Parvillez28. The company provided lighting for Lille for the better part of the nineteenth century, as well as for Marseille between 1837 and 1855, and Toulouse between 1840 and 185629.

At the same time, the gas industry extended to other regions. In 1834, the cities of Lyon, Roubaix, and Rouen signed a concession for public gas lighting. The process extended to Nancy and Tourcoing in 1835, Boulogne-sur-Mer and Tours in 1836, and Marseille, Dunkerque, and Saint-Étienne in 1837. An interest for modernity had won over the urban world, and the presence of this public service was seen as a sign of prosperity. In 1840, 35 French cities already had a concession, over half of which were the seat of the department. In 1850, 107 French municipalities had gas, 52 of which were the seat of the province.30 The expansion was even greater during the second half of the century. In 1891, 1,000 French municipalities were lit by gas, including 99 municipalities of more than 20,000 inhabitants, and even more remarkably, 90% of the 300 municipalities with 6,000-20,000 inhabitants, and half of the municipalities with 4,000-6,000 inhabitants. In other words, the citizens and enterprises of almost all French cities had access to a gas distribution network31.

Two primary reasons drove the introduction of this service. The first was connected to urban development, and the need for lighting to make cities safer at night. The second was connected to rising private demand for gas lighting. In some cities such as Paris and Lyon, this demand on the part of private individuals and merchants already represented 80% of sales before 1850. For example, the number of subscribers in Paris rose from 1,500 in 1826 to 25,000 in 1853 . During the same period in Lyon, after 20 years of activity, the Compagnie Lyonnaise de Perrache had over 7,000 subscribers, while in Strasbourg the Compagnie de l’union had over 4,000 subscribers in the mid-nineteenth century. The introduction of gas lighting in French daily life developed until gas became widespread in cafes and restaurants under the Second Empire (1850-1870)32.

With the development it had undergone since the mid-nineteenth century, gas triumphed in France at the end of the century. For instance, the Universal Exposition of 1889 was entirely lit by gas, and in 1900 there were some 60,000 gas lamps in Paris33.

The origin of the various gas companies depended on their developers. In some cases it was municipalities, in others local or foreign entrepreneurs. Early on these companies were especially founded thanks to the support of multiple people, as was the case with Gaz de Perrache in Lyon. As the profitability of gas plants increased, the presence of corporations in the sector increased, as their investors were entrepreneurs seeking to diversify their activities34.

The management of this industry was generally monopolistic, for in most French cities there was only one company providing this service. Only major cities had multiple companies, such as Paris (six), Lyon (four), Marseille (three), and Amiens (two). The profitability of companies competing in the same area was low, requiring them to find alternatives in order to make their activity viable. This is why entrepreneurs sought to secure the exclusivity of concessions, which became the primary method used in the French gas industry35.

Gas companies had to obtain from municipalities the right to establish and operate gas plants and distribution networks. There were essentially two enterprise models. The first involved large enterprises whose concessions extended across a major city and its suburbs, as with the Compagnie Parisienne, which was created from the merger of six pre-existing companies in Paris in 1855. The second involved other companies that were obliged–in order to remain in the market–to extend their field of action by combining multiple dispersed stakes, or by expanding their activities to also supply drinking water, and later to enter the electricity distribution sector. One example of this model is the Société Lyonnaise des eaux et de l’éclairage, which was founded in 1880 and based in Paris, and accumulated numerous gas and water distribution concessions in cities including Paris, Bordeaux, and Lille. Finally, there also existed transnational French companies, with the largest representative being Lebon, which as we will see later successfully built a major gas empire in Spain in the mid-nineteenth century36.

This growth in the gas industry was threatened by the arrival of a major competitor that would completely revolutionize the sector–electricity—although gas remained an important energy source in France during the twentieth century.

Back to topThe gas industry in nineteenth-century Spain

In Spain, while there is evidence of a few relatively early attempts at gas lighting, the diffusion of this energy was later, slower, and more modest than in other European countries such as France. In some cities, its entry was delayed until the 1880s, while in many others, the transition from traditional lighting systems to electricity happened directly, without the intermediate stage of gas37.

The gas industry arrived in Spain thanks to Charles Lebon of France, who on May 17, 1841 secured a concession from the City of Barcelona to provide gas lighting services38. In general, three stages stand out in the implementation of the public service of gas in Spain. First, from 1841 to 1880, the earliest gas initiatives emerged, as did the initial legal regulatory framework. The latter was characterized by a contract between city councils and companies, which evolved over time due to technical progress, the appearance of meters, and a better understanding of the new industry of networks. The second phase extended from approximately 1880 to 1913. This period saw the appearance of electricity and the resulting competition with the gas industry, as well as the greater role of the central administration, which sought to exert effective control over the regularity, security, and continuity of supply. In the third phase, between 1914 and 1936, strong state interventionism became effective in the context of major changes to the structure and management of enterprises39.

Foreign entrepreneurs and engineers played a crucial role in the initial development of the gas industry in Spain, especially the English and the French40. The scarcity of qualified native staff, especially when the activity was just beginning, was due among other things to the fact that Spain did not have engineering schools oriented toward training technicians for the private sector, unlike France. It did not have clearly established avenues for learning mechanics in workshops, and it was not until 1850 that the government planned for instruction in industrial development. Furthermore, the financial context was not favorable before the middle of the century, with the emergence of the modern bank. In particular, the passing of the Ley de Sociedades Anónimas de Crédito (Law on Joint-Stock Loan Companies) in 1856 enabled the development of industrial banks, primarily French, thereby promoting the expansion of the gas industry41.

However, beginning in the late 1850s, foreign engineers were replaced by waves of their Spanish counterparts. This process was linked to the emergence of industrial engineering in Spain in 1850, as mentioned above, but it can also be explained by the creation of enterprises with national capital. Most of them were Catalan, and their owners preferred using qualified local staff, which shows that entrepreneurs had the power to impose their preference for local technicians. Numerous industrial actors sent their children to study engineering, either in Spanish schools or abroad. Spanish engineers also found jobs in the administration, as municipalities and the government became aware of the need to control the quality and security of gas supply42.

In contrast to the strong presence of municipal management and property in a number of European regions (Germany, Scandinavia, major British cities), in Spain private companies were predominant, as was the case in France, Italy, and Belgium. For that matter, like in France, the power to grant a concession to occupy public property and operate this service in Spain was the remit of city councils43. Concessions were generally based on models established on the basis of early experiments that were improved over time, especially with regard to defining the quality of the service and its mechanisms of control. Obtaining exclusivity in public lighting was a central objective for gas companies, for they ensured a minimum level of demand in order to make profitable the high fixed costs of infrastructure44.

Another characteristic similar to the French model is that concessions also included the Scientific Progress Clause, which required gas companies to adopt new discoveries in the field of energy if they did not want to lose their concession. For example, if technological and scientific progress produced means of urban lighting that were less expensive or more effective than gas, companies would have to adopt them or lose the concession45.

From the standpoint of the system’s regulation, the characteristics of the gas industry, especially those connected to security–with respect to its extraction, production, and distribution–explain the regulatory standards of the state. It was a networked industry with characteristics similar to those in the supply of drinking water, with major initial investments that required considerable capital to deliver the product or service to the consumer46. Gas companies therefore had to have extensive financial capacity in order to avoid supply interruptions and to adapt the continuous technical changes linked to their production. In addition, the lack of coal in Spain required the import of very large quantities of this energy source.

These considerations helped make the supply of gas a natural monopoly. The externalities generated by this industry were very positive, including improvements in quality of life and the energy source, as well as a direct impact on the country’s economy. The implementation and gradual spread of this public service raised awareness among local and state entities regarding the need to intervene in this industrial activity. The guarantee of continuous product supply on the part of enterprises–with no arbitrary interruptions–along with consumer protection to avoid rate abuses became frequent criteria for municipal regulations. These were, in essence, the most pertinent reasons for justifying public regulation of the gas industry47.

The earliest legal framework for the gas industry in Spain emerged between 1840 and 1880. Gas lighting appeared for the first time in 1842, notably on Las Ramblas in Barcelona, with the creation of the Sociedad Catalana para el Alumbrado de Gas (Catalan Gas Lighting Company) in 1843. The development of the industry was accompanied by the strong presence of foreign companies, which also explains the heightened control exercised by the government48.

The first gas supply contract in Spain was concluded between the City of Barcelona and the Sociedad Catalana de Alumbrado de Gas, more commonly known by the name La Catalana, and its owner Charles Lebon. During those years, the agreements established certain essential points: the streets to be lit, the number of lamps, the lighting calendar, a minimum quality guarantee, measures to avoid service interruptions, and the rates to be paid by the city and consumers49.

The concessions were granted by public adjudication on an exclusive basis for a period between 15 and 50 years. This method represented a monopoly, and was the heir to the mercantilist practices of the Ancien Régime. In order to promote certain economic activities deemed essential, the state encouraged this type of action50. Constructing the gas pipelines required such prerogatives, and led to the preservation of the rights secured by these gas companies. This situation led to the exclusion of other competitors, which could not operate in the same area—notably with regard to public lighting—although this did not apply to the installation of pipes. Companies were required to supply any client who requested it. In order to avoid abuses by companies, beginning in the mid-nineteenth century city councils began to impose the Scientific Progress Clause, which provided for the exclusivity to be revoked if companies did not modernize their installations, improve their service, or reduce supply rates51.

In any event, due to unfamiliarity with gas activities, state legislation was very rare until 1850. Along the same lines, city councils did not develop an overly interventionist framework, limiting themselves to public lighting contracts for streets and plazas.

State legislation began with the Royal Order of February 27, 1852, which established the guidelines for the transference of public service markets. More precisely, it required public adjudication, in the name of the state, for markets involving all types of public services and works. This rule was not mandatory if they were exempted after two calls for proposals, or if they were conducted on an experimental basis. In the latter case, granting the concession had to be approved by the Council of Ministers52.

Auction sales connected to the gas industry were organized by municipal councils, although neither the conditions nor the regulations were clear, as they were often not even published. This aspect prompted doubts and uncertainty, which the Royal Orders of February 9 and April 8, 1858 sought to clear up by leaving public works and the lighting of municipalities under the aegis of municipal councils, all while granting the civil governor decision-making power in terms of adjudication53.

Despite the gradual appearance of these regulations, the legal framework was not completely defined, which led to frequent litigation between companies, users, and municipalities. In addition, public lighting rates were lower than those charged to private individuals. They were established at a fixed rate–one amount per lamp per hour–and only cities such as Barcelona had meters. In the 1860s, rates rose as the supply network extended to other neighborhoods.

With the spread of this public service and the awareness of authorities, controls became more effective. This more interventionist cycle within this first stage (1840-1880) unfolded from 1860 onward, when the national government became more vigilant toward private companies. For example, the Royal Order of 1860 established the marking and verification of meters as a means of ensuring the models accepted by the state, thereby avoiding fraudulent consumption. This standard marked the first central jurisdiction over this activity54.

The municipal laws of 1870 and 1877 ratified the concession to city councils of powers relating to public lighting. However, the latter regulation did not give them the ability to grant monopolies, as the Royal Orders of April 17, 1877 and June 11, 1879 limited this exclusively to public lighting. Along the same lines, the Royal Order of September 19 of the same year required city councils to proceed with bidding if the service budget rose to 50,000 pesetas or higher.

The 1860s and 1870s were marked by greater city control over gas companies. Earlier experience prompted the inclusion of a regulation requiring improvements in service, with the position of municipal inspector being created to that end. The average duration of contracts varied between 25 and 31 years55.

The implementation of the legal framework for concessions was marked by the economic, technical, and organizational incompetence of city councils during those years. Moreover, the ambient liberalism of the time was not particularly favorable to direct management by authorities,56 although municipalities had to intervene more and more. This was due to four reasons: the use of public property by enterprises, namely to dig holes in streets to lay pipes; an effort to avoid breach of contract; rate abuses that pestered consumers; and last but not least, because municipalities themselves were often the primary subscribers57.

The expansion of the gas industry in Spain was fairly modest. As mentioned above, Charles Lebon pioneered the industry’s development in Spain. He participated with local partners in the expansion of gas by securing concessions for public gas lighting in Barcelona (1842), Valencia (1843), and Cádiz (1845). Soon afterwards, Lebon momentarily left Spain, primarily due to disagreements with his Spanish partners, as well as the change in economic cycle in France resulting from the crisis of 1848. Despite difficulties, in March 1847 he founded in Paris the Compagnie Centrale d’Éclairage par le Gaz, Lebon et Cie., to which he gradually incorporated gas plants in Spain. At the end of the nineteenth century, he had 8 gas plants in Almería, Barcelona, Cádiz, Granada, Murcia, El Puerto de Santa María, Santander, and Valencia58.

Aside from Lebon’s company, there were two Spanish joint-stock companies: the Sociedad Catalana para el Alumbrado de gas, with plants in Barcelona and Sevilla, and the Sociedad Madrileña de Alumbrado por Gas, controlled by the Crédito Mobiliario, with concessions in six cities—Alicante, Burgos, Cartagena, Jerez de la Frontera, Pamplona, and Valladolid—where the corresponding plants were brought into service between 1859 and 186359.

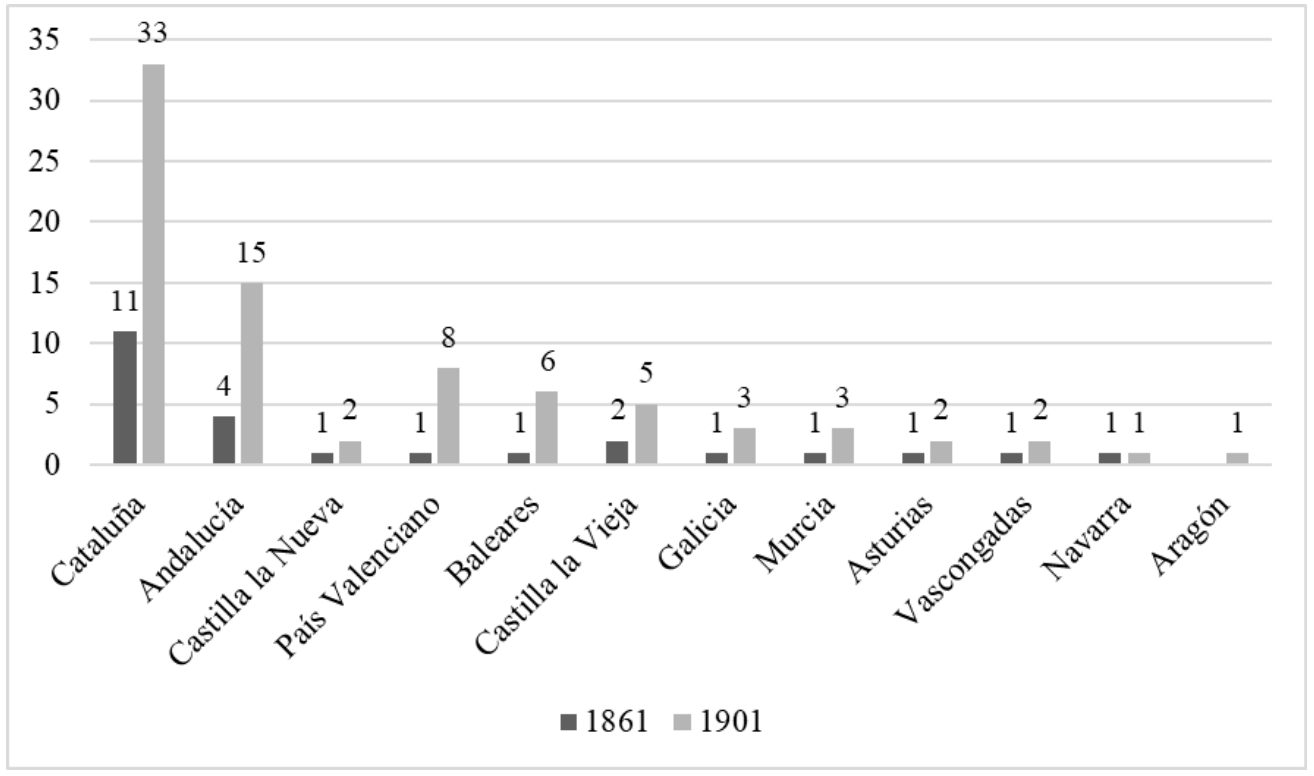

In 1861, there were just 25 plants in all of Spain, mostly concentrated in Catalonia (11 plants) and Andalusia, with the rest dispersed across maritime provinces, except for Madrid, Valladolid, and Pamplona. In 1901 Spain had 81 gas plants, with a highly unequal territorial distribution of gas-related establishments; Catalonia and the province of Cádiz had the highest concentration of gas plants, with 33 and 7 respectively (Figure 2)60.

Source: personal compilation based on Sudrià, “Notas sobre la implantación”, 108 (cf. note 48).

Conclusions

Since the mid-nineteenth century, the gas industry has undergone major transformations in Latin Europe, especially in France and Spain. The implementation and management of gas supply had a positive impact on the economic processes of both countries.

As demonstrated above, it is clear that a management model and/or public service regulation of gas lighting clearly existed in France and Spain, and involved the exclusive concession of this service to a private company. During the period in question, the dominant model in the two countries studied was the French model, which also spread to other European countries, although there were a few regions where the English model was applied (direct operation of the service by the local government), as in the case of Bordeaux in France, or Bilbao and San Sebastian in Spain.

Initially, service concessions were ambiguous, with local authorities not wanting to hinder their development, but over time concession contracts became more complex, and regulated numerous aspects. Rates and meters were the primary points of negotiation between the local government and the concessionary company in all regions.

In general, the management of this service in France proceeded via administrative concession, and the regulations used in the capital were then applied to the rest of French territory. In most cities, there was no more than one concessionary, except in major cities such as Paris, Lyon, Marseille, and Amiens, although profitability forced the industry to concentrate during the second half of the nineteenth century, and to even internationalize in order to remain viable. French city councils became increasingly interventionist, establishing prices and specifying rules for providing service.

Like in France, in Spain private companies were chosen for gas supply–and more specifically for the legal framework of the concession–given that in both countries the municipalization of gas distribution services was infrequent. This decision can be explained by the difficulties municipalities faced in directly managing public services, including limited expertise, insufficient financial resources, and limited possibilities for addressing the technological challenges of this new public service. Moreover, obtaining high-quality coal at a good price was a complex task for municipalities, whose administrative structure was still in the early stages.

Furthermore, in both Spain and France, the lack of municipal financial resources was a key factor in not opting for municipalization, as it would not have been possible to financially compensate gas companies. Spanish governments did not directly intervene in the regulation of gas supply. The Parliament did not have the power to approve the articles of incorporation of enterprises, to regulate gas company profits, or to create a reserve fund, and had no influence over rate controls. The most common practice was that of one supplier per municipality. With the exception of the cities of Barcelona and Cádiz, there was practically no competition. Along the same lines, the Spanish case shows that municipalities used concession contracts to establish the price for public and private lighting.

Finally, in both countries the sector developed based on a similar model and legislation. Spain was nevertheless late in introducing gas compared to France, and the lack of local investors favored the investment of foreign companies in this sector, which was the primary shared factor. French capital was dominant in Spain, with the gas sector in these countries being highly interconnected as a result. Any changes in technology and regulation were shared and applied after a certain time in the other country, as well as in other European countries, such that one could speak of a certain market unity, one that was limited by each country’s degree of protectionism at a particular moment in history.

- 1. Mercedes Arroyo Huguet, Ana Cardoso de Matos, “La modernización de dos ciudades: las redes de gas de Barcelona y Lisboa, siglos XIX y XX”, Scripta Nova. Revista Electrónica de Geografía y Ciencias sociales, vol. XIII, nº 296(6), 2009.

- 2. Mariano Castro-Valdivia, Juan Manuel Matés-Barco, María Vázquez-Fariñas, “The Regulation of Gas in Latin Europe (1850-1920)”, in Jesús Mirás-Araujo, Andrea Giuntini (ed.), The Gas Industry in Latin Europe. Economic Development During the 19th and 20th Centuries (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2023), 59-60.

- 3. Jean-Pierre Williot, Serge Paquier, “Origine et diffusion d’une technologie nouvelle au XIXe siècle”, in Serge Paquier, Jean-Pierre Williot (dir.), L’industrie du gaz en Europe aux XIXe et XXe siècles. L’innovation entre marchés privés et collectivités publiques (Bruxelles: Peter Lang, 2005), 24.

- 4. Alberte Martínez-López, Jesús Mirás-Araujo, “The Territorial Diffusion of the Gas Industry in Latin Europe Before the Competition from Electricity”, in Jesús Mirás-Araujo, Andrea Giuntini (ed.), The Gas Industry in Latin Europe. Economic Development During the 19th and 20th Centuries (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2023), 27.

- 5. Alberte Martínez-López, Jesús Mirás-Araujo, “La transferencia de tecnología en la Europa Latina: el papel de la Société Technique de l’Industrie du Gaz en France, 1895-1938”, Asclepio, vol. 73, nº 2, p563, 2021.

- 6. Arrêté préfectoral du 30 septembre 1822, traitant de la délimitation des zones de chaque compagnie à Paris.

- 7. Anselme Payen, L’éclairage au gaz (Paris: Librairie de L. Hachette et Cie, 1867), 6-13; Edmon Théry, La question du gaz à Paris, 3ª ed. (Paris: Publications de la Grande Encyclopédie Financère et Industrielle, 1882), 8; Jean-Pierre Williot, “De la naissance des compagnies à la constitution des groupes gaziers en France (années 1820-1930)”, in Serge Paquier, Jean-Pierre Williot (dir.), L’industrie du gaz en Europe aux XIXe et XXe siécles. L’innovation entre marchés privés et collectivités publiques (Bruxelles: Peter Lang, 2005), 150, 161.

- 8. Mercedes Fernández-Paradas, Antonio Jesús Pinto Tortosa, “La saga de los ingenieros británicos Manby y su contribución a la industria del gas en Francia y España (1776-1884)”, Asclepio, vol. 73, nº 2, p561, 2021.

- 9. Jean-Pierre Williot, Naissance d’un service public: le gaz à Paris (Paris: Éditions Rive Droite - Institut d’Histoire de l’Industrie, 1999), 50-64.

- 10. Idem, 61; Bulletin des Lois de L’Empire Français, XIe Série. Règne de Napoléon III, Empereur des Français. Partie supplémentaire. Tome Sixième. Contenant les décrets et arrêtes d’intérêt local ou particulier publiée depuis le 1er juillet 1855 jusqu'à 31 décembre inclusivement. N° 197 à 251, 1856. Imprimerie Impériale, 1167-1168.

- 11. Bulletin des Lois de L’Empire Français, 1168, 1174-1175 (cf. note 10); Pedro A. Fàbregas Vidal, La Globalización en el siglo XIX: Málaga y el gas (Sevilla: Ateneo de Sevilla - Universidad de Sevilla, 2003), 92.

- 12. María Vázquez-Fariñas, Mariano Castro-Valdivia, Juan Manuel Matés-Barco, “The Internationalisation of the British Gas Industry in Latin Europe in the Nineteenth Century”, in Ana Cardoso de Matos, Alexandre Fernandez, Antonio Jesús Pinto Tortosa (ed.), The Gas Sector in Latin Europe’s Industrial History. Lighting and Heating the World (Cham: Springer, 2023), 13-24.

- 13. Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, “L’émergence de la norme technique de sécurité en France vers 1820”, Le Mouvement Social, vol. 4, nº 249, 2014, 77.

- 14. Idem, 82-83.

- 15. Ibid., 80; Napoléon Bacqua de Labarthe, Codes de la législation française (Paris: Imprimerie et librairie administratives de Paul Dupont et Cie., 1858), 1316-1319.

- 16. Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, “Gaz, gazomètres, expertises et controverses. Londres, Paris, 1815-1860”, Le Courrier de l’environnement de l’INRA, nº 62, 2012, 48.

- 17. Bacqua, Codes de la législation, 1319-1320 (cf. note 15).

- 18. Thomas Le Roux, “La mise à distance de l’insalubrité et du risque industriel en ville: le décret de 1810 mis en perspectives (1760-1840)”, Histoire & Mesure, vol. XXIV, nº 2, 2009, 66.

- 19. Castro-Valdivia, Matés-Barco, Vázquez-Fariñas, “The Regulation of Gas”, 60 (cf. note 2).

- 20. Bacqua, Codes de la législation, 1335-1336 (cf. note 15).

- 21. Théry, La question du gaz, 11 (cf. note 7); Williot, “Naissance des compagnies”, 161 (cf. note 7).

- 22. Copagaz, “N° 04 - L’activité gazière et la concurrence - La maturité”, 2021. Url: https://www.copagaz.fr/copagaz/histoires-industrielles/12054-n-04-l-act… (accessed 10/04/2023)

- 23. Arroyo, Cardoso, “La modernización de dos ciudades” (cf. note 1).

- 24. Jacques Quehen, “L’industrie du gaz de ville en Normandie”, Études Normandes, vol. 14, nº 48, 1955, 202.

- 25. Bulletin des Lois du Royaume de France, 7a Série. Tome Dix-neuvième et dernier. Contenant les Lois et Ordonnances rendues depuis le 1er Juillet jusqu’à 16 Septembre 1824. Nos 680 à 689, 1825 [Bulletin de Lois nº 684 bis]. Imprimerie Royale, 1-5; Le Guide ou conducteur de l’étranger à Bordeaux, Département de la Gironde. Seconde Edition (Chez Fillastre et neveu, éditeurs, 1827), 419.

- 26. Bordeaux. Aperçu historique - sol, population, industrie, commerce - administration - publié par la municipalité bordelaise. Tome deuxième (Imprimerie G. Gounouilhou, 1892), 328-329.

- 27. Idem, 330-333; Société de Géographie Commerciale de Bordeaux, Bulletin nº 1, année 1874-75 (Imprimerie G. Gounouilhou, 1876), 50-51.

- 28. Calendrier de Lille, pour l’année 1830 (Chez L. Danel, 1830), 87.

- 29. Le Gaz. Journal des Producteurs et des Consommateurs des gaz, d’éclairage et de chauffage, 1er année - nº 12, 31 mai 1857 (Imprimerie Centrale de Napoléon Chaix et Ce., 1857a), 91-94; Le Gaz. Journal des Producteurs et des Consommateurs des gaz, d’éclairage et de chauffage, 1er année - nº 15, 30 juin 1857 (Imprimerie Centrale de Napoléon Chaix et Ce., 1857b), 107-112; Le Gaz. Journal des Producteurs et des Consommateurs des gaz, d’éclairage et de chauffage, 2e année - nº 4, 10 mars 1858 (Imprimerie Centrale de Napoléon Chaix et Ce., 1858), 28.

- 30. Williot, “Naissance des compagnies”, 150 (cf. note 7).

- 31. Alexandre Fernandez, “Suministrar gas y electricidad a las ciudades francesas antes de la ley de nacionalización de 1946”, Ayer, vol. 122, nº 2, 2021, 24.

- 32. Idem, 24-25; Williot, “Naissance des compagnies”, 151-152 (cf. note 7).

- 33. Copagaz, “N° 04 - L’activité gazière” (cf. note 22).

- 34. Williot, “Naissance des compagnies”, 152-153 (cf. note 7).

- 35. Castro-Valdivia, Matés-Barco, Vázquez-Fariñas, “The Regulation of Gas”, 62 (cf. note 2).

- 36. Fernandez, “Suministrar gas y electricidad”, 25 (cf. note 31).

- 37. Martínez-López, Mirás-Araujo, “La transferencia de tecnología” (cf. note 5).

- 38. Vázquez-Fariñas, Castro-Valdivia, Matés-Barco, “The Internationalisation of the British Gas” (cf. note 12).

- 39. Mercedes Fernández-Paradas, “La regulación del suministro de gas en España (1841-1936)”, Revista de Historia Industrial, vol. 25, nº 61, 2016, 49-78.

- 40. Mariano Castro-Valdivia, Juan Manuel Matés-Barco, “Los servicios públicos y la inversión extranjera en España (1850-1936): Las empresas de agua y gas”, História Unisinos, vol. 24, nº 2, 2020, 221-239.

- 41. Mercedes Fernández-Paradas, Carlos Larrinaga, Juan Manuel Matés-Barco, “Los ingenieros y el suministro de gas en la España del siglo XIX”, Revista de Historia Industrial, vol. 30, nº 83, 2021, 44-45.

- 42. Idem, 45.

- 43. Alexandre Fernandez, “Cambio tecnológico y transformaciones empresariales: gas y electricidad en Bilbao y en Burdeos (ca. 1880-ca. 1920)”, Historia contemporánea, nº 25, 2002, 321.

- 44. Alberte Martínez-López, Jesús Mirás-Araujo, “La ciudad como negocio: gas y empresa en una región española, Galicia 1850-1936”, Documentos de Trabajo FUNCAS, nº 536, 2010.

- 45. Mercedes Arroyo, “Actitudes empresariales y estructura industrial. El gas de Málaga, 1854-1929”, Scripta Nova. Revista electrónica de Geografía y Ciencias Sociales, vol. X, nº 215, 2006.

- 46. Víctor M. Heredia-Flores “Municipalización y modernización del servicio de abastecimiento de agua en España: el caso de Málaga (1860-1930)”, Agua y Territorio / Water and Landscape, nº 1, 2013, 103-117.

- 47. Castro-Valdivia, Matés-Barco, Vázquez-Fariñas, “The Regulation of Gas”, 63-64 (cf. note 2).

- 48. Carles Sudrià. “Notas sobre la implantación y el desarrollo de la industria de gas en España, 1840-1901”, Revista de Historia Económica / Journal of Iberian and Latin American Economic History, nº 2, 1983, 104-105; Mercedes Arroyo, “El gas de Madrid y las compañías de crédito extranjeras en España, 1856-1890”, Scripta Nova. Revista electrónica de Geografía y Ciencias Sociales, vol. VI, nº 131, 2002; Castro-Valdivia Mariano, Fernández-Paradas Mercedes, Matés-Barco Juan Manuel, “Las empresas extranjeras de agua y gas en España (circa 1900-1923)”, in Juan Manuel Mátés-Barco, Alicia Torres-Rodríguez (ed.), Los servicios públicos en España y México (Madrid: Silex, 2019), 51-74.

- 49. Castro-Valdivia, Matés-Barco, Vázquez-Fariñas, “The Regulation of Gas”, 64-65 (cf. note 2).

- 50. Fernández-Paradas, “La regulación del suministro”, 55 (cf. note 39).

- 51. Idem, 54; Martínez-López Alberte, Mirás-Araujo Jesús, “The city as a business: gas and business in the Spanish region of Galicia, 1850-1936”, Continuity and Change, vol. 27, nº 1, 2012, 131.

- 52. Gaceta de Madrid, 29 de febrero de 1852.

- 53. Castro-Valdivia, Matés-Barco, Vázquez-Fariñas, “The Regulation of Gas”, 64 (cf. note 2).

- 54. Fernández-Paradas, “La regulación del suministro”, 51 (cf. note 39).

- 55. Castro-Valdivia, Matés-Barco, Vázquez-Fariñas, “The Regulation of Gas”, 66 (cf. note 2).

- 56. Íñigo Del Guayo, El servicio público del gas (Madrid: Marcial Pons, 1992), 32.

- 57. Castro-Valdivia, Matés-Barco, Vázquez-Fariñas, “The Regulation of Gas”, 66 (cf. note 2).

- 58. Mercedes Fernández-Paradas, “Empresas y servicio de alumbrado público por gas en España (1842-1935)”, TST. Transportes, Servicios y Telecomunicaciones, nº 16, 2009, 109-131.

- 59. Sudrià, “Notas sobre la implantación”, 103-105 (cf. note 48).

- 60. Idem, 106-107.

Printed sources

Arrêté préfectoral du 30 septembre 1822, traitant de la délimitation des zones de chaque compagnie à Paris.

Bordeaux. Aperçu historique - sol, population, industrie, commerce - administration - publié par la municipalité bordelaise. Tome deuxième. Imprimerie G. Gounouilhou, 1892.

Bulletin des Lois du Royaume de France, 7a Série. Tome Dix-neuvième et dernier. Contenant les Lois et Ordonnances rendues depuis le 1er Juillet jusqu’à 16 Septembre 1824. Nos 680 à 689, 1825. [Bulletin de Lois nº 684 bis]. Imprimerie Royale.

Bulletin des Lois de L’Empire Français, XIe Série. Règne de Napoléon III, Empereur des Français. Partie supplémentaire. Tome Sixième. Contenant les décrets et arrêtes d’intérêt local ou particulier publiée depuis le 1er juillet 1855 jusqu’à 31 décembre inclusivement. Nos 197 à 251, 1856. Imprimerie Impériale.

Calendrier de Lille, pour l’année 1830 (Chez L. Danel, 1830).

Gaceta de Madrid, 29 de febrero de 1852.

Le Gaz. Journal des Producteurs et des Consommateurs des gaz, d’éclairage et de chauffage, 1er année - nº 12, 31 mai 1857 (Imprimerie Centrale de Napoléon Chaix et Ce., 1857a).

Le Gaz. Journal des Producteurs et des Consommateurs des gaz, d’éclairage et de chauffage, 1er année - nº 15, 30 juin 1857 (Imprimerie Centrale de Napoléon Chaix et Ce., 1857b).

Le Gaz. Journal des Producteurs et des Consommateurs des gaz, d’éclairage et de chauffage, 2e année - nº 4, 10 mars 1858 (Imprimerie Centrale de Napoléon Chaix et Ce., 1858).

Le Guide ou conducteur de l’étranger à Bordeaux, Département de la Gironde. Seconde Edition (Chez Fillastre et neveu, éditeurs, 1827).

Société de Géographie Commerciale de Bordeaux, Bulletin nº 1, année 1874-75 (Imprimerie G. Gounouilhou, 1876).

Bibliography

Arroyo Mercedes, « El gas de Madrid y las compañías de crédito extranjeras en España, 1856-1890 », Scripta Nova. Revista electrónica de Geografía y Ciencias Sociales, vol. VI, nº 131, 2002. Url: https://www.ub.edu/geocrit/sn/sn-131.htm (accessed 15/04/2023)

Arroyo Mercedes, « Actitudes empresariales y estructura industrial. El gas de Málaga, 1854-1929 », Scripta Nova. Revista electrónica de Geografía y Ciencias Sociales, vol. X, nº 215, 2006. Url: http://www.ub.es/geocrit/sn/sn-215.htm (accessed 28/04/2023).

Arroyo Huguet Mercedes, Cardoso de Matos Ana, « La modernización de dos ciudades: las redes de gas de Barcelona y Lisboa, siglos XIX y XX », Scripta Nova. Revista Electrónica de Geografía y Ciencias sociales, vol. XIII, nº 296(6), 2009. https://www.ub.edu/geocrit/sn/sn-296/sn-296-6.htm

Bacqua de Labarthe Napoléon, Codes de la législation française (Paris: Imprimerie et librairie administratives de Paul Dupont et Cie., 1858).

Castro-Valdivia Mariano, Fernández-Paradas Mercedes, Matés-Barco Juan Manuel, « Las empresas extranjeras de agua y gas en España (circa 1900-1923) », in Juan Manuel Mátés-Barco, Alicia Torres-Rodríguez (ed.), Los servicios públicos en España y México (Madrid: Silex, 2019), 51-74.

Castro-Valdivia Mariano, Matés-Barco Juan Manuel, « Los servicios públicos y la inversión extranjera en España (1850-1936): Las empresas de agua y gas », História Unisinos, vol. 24, nº 2, 2020, 221-239. https://doi.org/10.413/hist.2020.242.05

Castro-Valdivia Mariano, Matés-Barco Juan Manuel, Vázquez-Fariñas María, « The Regulation of Gas in Latin Europe (1850-1920) », in Jesús Mirás-Araujo, Andrea Giuntini (ed.), The Gas Industry in Latin Europe. Economic Development During the 19th and 20th Centuries (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2023), 53-81. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-16309-8_3

CCSC Section Généalogie. Section du club de la CMCAS des Hauts-de-Seine des Industries électriques et gazières

« Tableau d’Honneur des Électriciens et Gaziers - 1914-1918 », 2004. Url: http://ccsc.genealogie.free.fr/TH/societes-SGP.htm (accessed 10/04/2023).

Copagaz, « N° 04 - L’activité gazière et la concurrence - La maturité », 2021. Url: https://www.copagaz.fr/copagaz/histoires-industrielles/12054-n-04-l-act… (accessed 10/04/2023)

Del Guayo Íñigo, El servicio público del gas (Madrid: Marcial Pons, 1992).

Fàbregas Vidal Pedro A., La Globalización en el siglo XIX: Málaga y el gas (Sevilla: Ateneo de Sevilla - Universidad de Sevilla, 2003).

Fernandez Alexandre, « Cambio tecnológico y transformaciones empresariales: gas y electricidad en Bilbao y en Burdeos (ca. 1880-ca. 1920) », Historia contemporánea, nº 25, 2002, 319-342.

Fernandez Alexandre, « Suministrar gas y electricidad a las ciudades francesas antes de la ley de nacionalización de 1946 », Ayer, vol. 122, nº 2, 2021, 21-42. https://doi.org/10.55509/ayer/122-2021-02

Fernández-Paradas Mercedes, « Empresas y servicio de alumbrado público por gas en España (1842-1935) », TST. Transportes, Servicios y Telecomunicaciones, nº 16, 2009, 109-131.

Fernández-Paradas Mercedes, « La regulación del suministro de gas en España (1841-1936) », Revista de Historia Industrial, vol. 25, nº 61, 2016, 49-78. https://doi.org/10.1344/rhi.v25i61.21331

Fernández-Paradas Mercedes, Larrinaga Carlos, Matés-Barco Juan Manuel, « Los ingenieros y el suministro de gas en la España del siglo XIX », Revista de Historia Industrial, vol. 30, nº 83, 2021, 43-72. https://doi.org/10.1344/rhiihr.v30i83.31307

Fernández-Paradas Mercedes, Pinto Tortosa Antonio Jesús, « La saga de los ingenieros británicos Manby y su contribución a la industria del gas en Francia y España (1776-1884) », Asclepio, vol. 73, nº 2, p561, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3989/asclepio.2021.19

Fressoz Jean-Baptiste, « Gaz, gazomètres, expertises et controverses. Londres, Paris, 1815-1860 », Le Courrier de l’environnement de l’INRA, nº 62, 2012, 31-56.

Fressoz Jean-Baptiste, « L’émergence de la norme technique de sécurité en France vers 1820 », Le Mouvement Social, vol. 4, nº 249, 2014, 73-89. https://doi.org/10.3917/lms.249.0073

Heredia-Flores Víctor M., « Municipalización y modernización del servicio de abastecimiento de agua en España: el caso de Málaga (1860-1930) », Agua y Territorio / Water and Landscape, nº 1, 2013, 103-117. https://doi.org/10.17561/at.v1i1.1038

Le Roux Thomas, « La mise à distance de l’insalubrité et du risque industriel en ville: le décret de 1810 mis en perspectives (1760-1840) », Histoire & Mesure, vol. XXIV, nº 2, 2009, 31-70. https://doi.org/10.4000/histoiremesure.3957

Martínez-López Alberte, Mirás-Araujo Jesús, « La ciudad como negocio: gas y empresa en una región española, Galicia 1850-1936 », Documentos de Trabajo FUNCAS, nº 536, 2010.

Martínez-López Alberte, Mirás-Araujo Jesús, « The city as a business: gas and business in the Spanish region of Galicia, 1850-1936 », Continuity and Change, vol. 27, nº 1, 2012, 125-150. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0268416012000082

Martínez-López Alberte, Mirás-Araujo Jesús, « La transferencia de tecnología en la Europa Latina: el papel de la Société Technique de l’Industrie du Gaz en France, 1895-1938 », Asclepio, vol. 73, nº 2, p563, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3989/asclepio.2021.21

Martínez-López Alberte, Mirás-Araujo Jesús, « The Territorial Diffusion of the Gas Industry in Latin Europe Before the Competition from Electricity », in Jesús Mirás-Araujo, Andrea Giuntini (ed.), The Gas Industry in Latin Europe. Economic Development During the 19th and 20th Centuries (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2023), 25-52. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-16309-8_2

Payen Anselme, L’éclairage au gaz (Paris: Librairie de L. Hachette et Cie, 1867).

Quehen Jacques, « L’industrie du gaz de ville en Normandie », Études Normandes, vol. 14, nº 48, 1955, 197-224. https://doi.org/10.3406/etnor.1955.3185

Sudrià Carles, « Notas sobre la implantación y el desarrollo de la industria de gas en España, 1840-1901 », Revista de Historia Económica / Journal of Iberian and Latin American Economic History, nº 2, 1983, 98-118. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0212610900012696

Théry Edmon, La question du gaz à Paris, 3ª ed. (Paris: Publications de la Grande Encycolpédie Financère et Industrielle, 1882).

Vázquez-Fariñas María, Castro-Valdivia Mariano, Matés-Barco Juan Manuel, « The Internationalisation of the British Gas Industry in Latin Europe in the Nineteenth Century », in Ana Cardoso de Matos, Alexandre Fernandez, Antonio Jesús Pinto Tortosa (ed.), The Gas Sector in Latin Europe’s Industrial History. Lightning and Heating the World (Cham: Springer, 2023), 13-24. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-36674-1_3

Williot Jean-Pierre, « De la naissance des compagnies à la constitution des groupes gaziers en France (années 1820-1930) », in Serge Paquier, Jean-Pierre Williot (dir.), L’industrie du gaz en Europe aux XIXe et XXe siécles. L’innovation entre marchés privés et collectivités publiques (Bruxelles: Peter Lang, 2005), 147-179.

Williot Jean-Pierre, Naissance d’un service public: le gaz à Paris (Paris: Éditions Rive Dorite - Institut d’Histoire de l’Industrie, 1999).

Williot Jean-Pierre, Paquier Serge, « Origine et diffusion d’une technologie nouvelle au XIXe siècle », in Serge Paquier, Jean-Pierre Williot (dir.), L’industrie du gaz en Europe aux XIXe et XXe siècles. L’innovation entre marchés privés et collectivités publiques (Bruxelles: Peter Lang, 2005), 21-52.