“Blue-Eyed Arabs” & the Silver Snake: Alaskan petrocultures and the Trans-Alaska pipeline system

University of Alaska Fairbanks

Pawight[at]Alaska.edu

Following fierce construction controversies in the late 1960s and the early 1970s, the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System became a familiar cultural hallmark and the most iconic pipeline in the world. This article argues that the realization of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System changed Alaska’s culture and global imaginaries of Alaska. TAPS forged overlapping and evolving petrocultures; rather than a uniform and static oil culture, the pipeline’s social valence ebbed and flowed with the passage of time and the transit of Arctic oil from Prudhoe Bay through Prince William Sound. The pipeline became a gauge not only for the State’s revenues, but also for the economic and cultural consciousness of its people. Yet there was always a subset of Alaskans who warned of the deleterious effects of the pipeline on Alaska’s environment, polity, culture and ancestral lifeways.

In late 1991, U.S. President George H.W. Bush uttered perhaps the strangest statement in history concerning a hydrocarbon pipeline: “The Caribou love it. They rub up against it, and they have babies.”1 Bush was referring to the famous Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS), in the context of the fiery debate over drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) in northeastern Alaska. At a December 1991 fundraiser dinner for U.S. Senator Frank Murkowski (R-AK), Bush elaborated on TAPS, Caribou and drilling in ANWR: “the critics said years ago when the debate was on the pipeline up there, the Alaska pipeline, that caribou would be extinct because of this. Well, there’s so many caribou they’re rubbing up against the pipeline, they’re breeding like mad.”2

American citizens likely found Bush’s reference of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System—even in its most bizarre aphrodisiac reference— a familiar cultural symbol. The pipeline provided the indispensable energy infrastructure to transport oil from the Prudhoe Bay field—the single largest conventional oil reservoir ever discovered on the North American continent—to the world’s most voracious energy consumers in the “lower 48” United States. Following the fierce controversy surrounding its construction and operation throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the Alaska Pipeline became perhaps the most famous—and certainly the most iconic and photographed—pipeline in the world. Since the late 1970s, when news articles discussed any pipeline around the world, they often portrayed TAPS—since it’s one of the few elevated hydrocarbon pipeline systems in the world. It is perhaps the only petroleum project for which numerous children’s books have been written.3 Like Hoover Dam or the Panama Canal, TAPS served as a cultural icon for American ingenuity, the prowess of modern engineering, and the proclaimed mastery of the natural world.

If the pipeline was an international icon, it became especially freighted with meaning for Alaskans. The construction of the pipeline system—at the time the largest private-capital project in world history—transformed the young polity of Alaska into a petrostate. Following the construction of TAPS, the vast majority of the state’s revenue flowed directly from the operation of the pipeline and the export of oil. The construction of the pipeline transformed Alaska from one of the poorest to one of the richest states in America. For Alaskans it is known simply as “the pipeline.” It is the state’s “main economic vein” and the facilitator of forty years of petro-prosperity.4 To others it constitutes a violation of Alaska itself—of its wilderness, its political independence, and its promise as a refuge from industrialism. Regardless of how Alaskans feel about the influence of the pipeline, it’s undeniably an international cultural icon.

This essay looks at petroculture specifically in relationship to one charismatic and outsized hydrocarbon infrastructure. While numerous books and articles have been written on TAPS, none have specifically focused on petroculture and how the infrastructure transformed Alaska’s culture between the 1970s and the present. As such, this essay aims to bring energy and Alaskan history into conversation with petrocultural studies. Much of the extant work on TAPS falls into two categories: environmentalist or boosterism. Environmental narratives tend to denounce the pipeline for despoiling Alaska’s pristine wilderness, while booster lauder engineers for overcoming herculean challenges.5 The works in both these categories tend to reflect a simplistic moral narrative of the pipeline and overlook its convoluted history. There are several excellent academic sources which overcome this problematic binary, but these texts offer their own scholarly limitations. Quite simply, those texts that focus on building the pipeline neglect its legacy and broad geographical impacts, while those texts that examine the environmental consequences of Alaskan oil often fail to recognize the historical influence and endurance of the system.6 This work aims to redress these gaps and offer a wide-ranging history of TAPS and Alaskan petroculture.

Petroleum and the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System were the crucial energy source and infrastructure which undergirded and co-created much of modern Alaskan society. Since its approval in 1973, TAPS has been the most important economic facility in the state. As the only infrastructure for exporting oil from Alaska’s North Slope, the pipeline was the keystone which permitted Alaskan Arctic oil production.7 The “Silver Snake” also serves as an instructive infrastructure for understanding the ebbs and flows of Alaska’s petroculture, as well as the rise and fall of oil fortunes in the far north.8 This study is not exhaustive, but aims to capture some of the prevailing currents which reflected Alaska’s cultural consciousness.

Petroculture has emerged as a valuable theoretical lens to understand the influence of petroleum in the production and reproduction of culture.9 Environmental historians have long noted the intimate relationship between energy sources and social dynamics, with scholar John McNeill arguing that each civilization can be organized by its “energy regime”.10 Petrocultural studies takes this insight further, moving beyond material conditions and analyzing the identities and practices of cultures situated within hydrocarbon production and consumption. Petroculture can be seen not only in cultural products like film, literature and music, but also the broader set of social values and conventions like political culture. Petroculture has been variously theorized as foundational to modern consumer culture, an entire phase of capitalism, and advanced through cultural strategies of evasion and denial.11

Despite excellent existing scholarship, petroculture has too often been treated as static, hegemonic, and harmonic. The history of TAPS demonstrates how conceptions of petroculture provide an invaluable lens to understand Alaskan society, but also why additional attention to temporality, social tension and omnipresent fossil resistance is necessary. This essay offers a historically nuanced conception of petroculture that pays particular attention to changing cultural conceptions over time, dissonant cultural trends, and the power of infrastructure in shaping social norms and expectations. While scholars of petroculture have paid particular attention to the production and consumption of hydrocarbons, the history of TAPS demonstrates the centrality of analyzing other aspects of the petroleum supply chain, namely infrastructures like pipelines, tankers, and refineries.

The construction and endurance of TAPS forged overlapping and evolving petrocultures. Rather than a uniform and static oil culture, the pipeline’s social significance ebbed and flowed with the passage of time and the uneven transit of oil from Prudhoe Bay through Prince William Sound. The pipeline itself became the gauge for not only the State’s revenues, but for the economic and cultural consciousness of its people. According to Alaskan journalist Elizabeth Harball, oil production at Prudhoe Bay and the construction and operation of TAPS “led to the state’s highest highs and lowest lows.”12 TAPS became the indispensable artery fueling the beating heart of Alaskan state and society.

The controversy, construction, and operation of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System changed Alaska’s culture dramatically; it also transformed American and global cultural imaginaries of Alaska. Journalists, commentators, and critics began referring to Alaskans after the discovery of Prudhoe Bay as “Blue Eyed Arabs.” In the midst of the 1970s oil crises, this capacious term offered a combination of exoticism, orientalism, and jealously for the suddenly-rich people of Alaska. Yet this term was sometimes embraced by Alaskans themselves, who used the phrase in a tongue-in-cheek fashion.13 Whether intentional or not, “Blue Eyed Arabs” also communicated long standing tropes about Alaska not being fully American because of its large Alaska Native population. The term also elided the fact that Alaska Natives were now major contributors, stakeholders, and—at times—victims of the oil industry. Commentators also used to the term refer to other northern states—especially Scotland, Norway, and Alberta—who became major oil producers during the 1970s and 1980s.14 Blue Eyed Arabs communicated that while the center of gravity of the global oil industry had shifted to the Middle East following World War Two, Western nations were shifting their petroleum industries to the far north and these peoples would now confront the burdens and prospects of oil wealth.

Alaska experienced four distinct petrocultural eras related to TAPS. Each of these political-economic periods changed and shaped the culture of Alaska.

First, the sheer enormity of the proposed pipeline system and its impact on the far north created a “maelstrom of change”, in the words of Alaska’s Governor Jay Hammond. Alaska came to be seen less as a military outpost (as it had been in the 1950s) and more as an emerging oil state. At the same time, a Native political revolution and unprecedented environmental movement stalled the pipeline, forced major reforms, and reconfigured social relations across society. The pipeline became the site of extraordinary contestation over oil development and the future of what many perceived as the nation’s last great wilderness.

Second, the construction and early operation of the pipeline helped to create nothing less than “a new social order” for Alaska. Few periods in Alaskan history were so transformational, unsettling, and frenetic as 1974-85. By the end of this period, Alaskans had reconfigured their political economy and created a novel society which journalist James Fallows called a “Boreal super state”. The State’s population effectively doubled—changing the culture, values, and collective politics of Alaska. The period made Alaskans rich, but also made state government far more volatile and dependent as Alaskans shifted their political economy to run on oil.

Third, the halcyon oil years gave way to the one-two punch of a double bust in the late 1980s and early 1990s as oil prices plummeted, a major recession gripped Alaska, and the Exxon Valdez oil spill desolated Prince William Sound. These years underscored some of the costs of the oil age, but did not fundamentally change Alaska’s deeply ingrained relationship with oil revenue. These years also witnessed the intensifying campaign to drill in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, which highlighted a divergence between Alaska’s oil culture and national environmental currents opposed to petroleum extraction in areas of the Arctic perceived as sacred.

Fourth, modern Alaska’s economy and society in the 21st C. has matured and diversified, heralding a new era of “Arctic Ambivalence” that has come to dominant major elements of Alaskan society. Alaskans are on the front lines of global climate change—experiencing more wildfires, coastal erosion, and permafrost thaw—yet large numbers of Alaskans remain committed to an extractive hydrocarbon economy. Despite being more economically and socially mature, paradoxically Alaskans seem less able to envision—much less realize—an economy and culture beyond oil. In the 21st C., Alaskans are trapped in the political economy and society they created with the construction of TAPS.

Back to top“Maelstrom of Change” (1968-1973)

On December 27th 1967, a crew of wildcatters from the Atlantic-Richfield Oil Company (ARCO) felt the roar of natural gas shake the earth from their drill on Alaska’s North Slope. Three months later, the oil explorationists formally discovered an underground ocean of oil beneath this prolific gas cap and the world soon had a new geographical term that was synonymous with oil abundance: “Prudhoe Bay.” At the time Alaska was one of the poorest American states, yet most realized it was rich in natural resources. Vic Fisher, the youngest participant at the Alaska Constitutional Convention in 1958, recalled feeling that Alaska was on the verge of something “very big”.15

Alaska was front-page news around the world as journalists, politicians, and the public fixated on two salacious developments: the state’s nearly billion-dollar lease sale (at the time the largest in world history) and the confounding issue of how to get the oil from the remote and forbidding North Slope to market. This international attention shifted narratives of Alaska from a 1950s military stronghold to a state gripped by oil fever.16 During this period journalists began using phrase “Blue Eyed Arabs”, yet this short-hand for Alaska’s publicly-owned oil wealth elided the austerity common throughout the state. This only began to change in September 1969, when Alaska held an oil lease sale for North Slope parcels adjacent to Prudhoe Bay and received $900 million dollars—nine times the state’s annual budget.17 “Alaska has become established as America’s greatest oil province”, declared Alaskan Governor Bill Egan in a 1970 speech; “Ponder for a moment the promise, the dream, and the touch of destiny.”18

Alaska’s culture—especially in its largest settlements—became enveloped by the boom-town mentality which had pervaded its past resource rushes. Oil companies—especially the “big three” of Humble (Exxon), British Petroleum, and Atlantic-Richfield (ARCO)—moved quickly to plan a pipeline from the North Slope to tidewater. They did not consult the Federal Government, the State of Alaska, or Alaska Natives before deciding the technology and route of their proposed Trans-Alaska Pipeline System from Prudhoe Bay to Valdez.

The oil rush caused significant ecological harm and social turmoil. “We suffered serious trespass”, recalled Eben Hopson, an Inupiaq elder and mayor of the North Slope Borough. Oil companies bulldozed Inupiaq fish camps and ancestral sites on the North Slope, disrupted ancient caribou migration routes, and left behind “the junk of oil exploration” according to Hopson.19 In its haste to exploit the rush, the State of Alaska bulldozed a hastily-planned winter road called the “Hickel Highway” to the North Slope. The state created the exact kind of ecological disaster and public relations fiasco the oil industry wished to avoid.20

The prospect of a billion-dollar pipeline alarmed two insurgent social groups: Alaska Natives and environmentalists. Two lawsuits by the Native community of Stevens Village and national environmental organizations, respectively, stalled the pipeline project in April 1970. The fallout of the Native court victory sent “ricochets…from Houston to Fairbanks”, the Seattle Times reported, and warned that “the project could be dead altogether.”21 Most pro-development Alaskans fumed as the pipeline project and its associated work contracts sputtered to a halt. After receiving death threats, the lawyer representing Alaska Natives was offered armed guards for protection.22 Jim Kowalsky, one of the founders of the Fairbanks Environmental Center, recounted a neighbor refusing to help when his car wouldn’t start in -30 Fahrenheit winter temperatures because of Kowalsky’s work opposing the pipeline.23

The lawsuits forced TAPS owner companies to lobby Congress and help to resolve outstanding indigenous land claims, which culminated in the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971 (ANCSA). ANCSA provided roughly one billion dollars and forty-four million acres of land to Alaska Natives, and created a pipeline right-of-way through the center of Alaska. The law proved a cultural watershed because it tied native justice to oil development and empowered a new category of for-profit native corporations. Half a billion dollars, more than half of the total settlement monies, would only be granted if Alaskan oil development and TAPS went forward. “I cannot overemphasize the feeling of betrayal that would occur among Native people of Alaska”, Alaska Federation of Natives President Don Wright wrote President Nixon in May of 1972, “if there is further delay in issuing the pipeline permit.”24 Additionally, ANCSA transformed Alaska Native communities because it provided the money and land to a dozen for-profit Native regional corporations who now had a fiduciary responsibility to their new shareholders. Via the pipeline controversy, oil companies, pro-development politicians, and even some native elites attempted to remake Alaska Natives in the image of American capitalism.

Throughout the United States, TAPS became the most contested infrastructure project in the early 1970s due to environmental concerns. For many Americans, the line symbolized not just an invasion of the America’s last wilderness, but also the profligacy of American society. All across the nation, citizens voiced their opposition—from the National Rifle Association to schoolchildren in Ohio, to the Audubon Society.25 Broad public concern over the pipeline reflected an extraordinary diversity of concerns. Carl Pope of Zero Population Growth (who later became Executive Director of the Sierra Club), told an audience in 1971 that if Americans switched to a two-child family “we would save far more fuel than the Alaska pipeline can provide.”26 The battle over TAPS was not simply about saving Alaska’s wildlife and wilderness, it was a contest between low-carbon conservation and refueling America’s high-energy petroculture.

In the summer of 1973, with oil becoming more scare, the U.S. Senate voted that TAPS had satisfied the requirements of the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 to expedite its approval. In October, the Arab Oil Embargo gripped the Western world and skyrocketed oil prices up four hundred percent. In November 1973, President Nixon signed the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Authorization Act into law, which declared TAPS in the “national interest…because of growing domestic shortages and increasing dependence upon insecure foreign sources.”27 800-miles of pipeline were America’s foremost answer to the gas lines that would come to define the nation’s fraught relationship with petroleum during the oil crisis.

Back to top“A New Social Order” (1974-1985)

When Congress approved the pipeline and work began full bore in early 1974, this ultimately brought about nothing less than a new Alaskan social order: a new population, a new built environment, new native corporations, and new widespread oil wealth. The pipeline boom effectively doubled the population of Alaska, and permanently changed its cultural dynamics and complexion. The pipeline also brought tremendous new wealth for the young state of Alaska and its citizens. With this wealth came a new built environment, as cities rapidly expanded, and new roads, buildings and capital projects emerged throughout the state. The construction of the pipeline and the following oil age transformed Alaska from one of the poorest to the richest state in the union.

Even in towns a thousand miles away from the physical project itself, the intensity and scale of pipeline construction loomed over the entire state. Following congressional approval in 1973, construction first began in the Spring of 1974 on the Haul Road to the North Slope, with pipeline construction reaching peak intensity in 1975 and 1976. Alaska’s economic growth rate tripled in the first four months of 1975, compared to a year before, which itself was double the pre-construction year of 1973.28 Costing in excess of $15 billion, TAPS vastly overshadowed Alaska’s entire economy, which was only 1.5 billion in 1973.29

Over 70,000 people worked on the project between 1974-1977, with a peak construction workforce exceeding 28,000 people in 1976. The project famously attracted workers from across the country, but Alyeska and its contractors had preferential hiring for Alaskan citizens, Alaska Natives, and women. Almost ten percent of the pipeline’s total workforce were women, and their entrance into a typically-male field symbolized the affirmative action efforts of the era.30

The approval of the construction dramatically increased in-migration to Alaska, with tens of thousands of people moving to Alaska from the lower forty-eight—especially oil states like Texas and Oklahoma. The influx of these individuals would significantly change the culture of Alaska, and “sourdoughs” who had been here before the pipeline called these folks “Tex-Alaskans”. Pointed points, cowboy hats, and large belt buckles announced these new Alaskans. Country singers like Sam Little, who wrote and performed the Alaska pipeline song Trucking on the Kamikaze Trail in 1976, celebrated and commemorated the work being done by these blue-collar workers.31 Even more consequentially, Alaska’s newest residents brought with them different cultural beliefs, political preferences, and religious practices to the last frontier.32

The high salaries—as much as $1,000-1,700 per week—during a period of recession in the United States caused a new “black gold rush”. These dynamics proved especially salient since, in the pre-pipeline years, those emigrating to Alaska were typically moving to seek a new lifestyle, get away from people and the pressures of fast-paced life; while the new arrivals were coming to Alaska very explicitly for monetary reasons. “This state is like a great big bottle of megabucks—big bucks that distort men’s minds, visions, and values,” reflected journalist Edward Fortier in 1975.33 Yet many also came and did not find fortune—they waited in long lines at union halls, often with no luck. Despite the pipeline boom, Alaska had the same unemployment rate as the lower 48.34

For Alaskans, everyday life amidst pipeline construction offered a mix of the profane and quotidian. With the boom came drinking, prostitution, crime, and general excess that followed the highest paid blue-collar jobs in the United States, if not the world at the time. These stories of debauchery garnered the most attention, but did not reflect the cultural experiences of everyday Alaskans. In contrast to the outside newspapers who portrayed Fairbanks and Anchorage as “Gommorahs of the Far North”, according to veteran journalist Dermot Cole, everyday life continued for Alaskans, who brought their kids to school, walked their dogs, and tried to live with some semblance of normalcy amidst the tumult.35

In a similar contrast, Alaskan material culture during pipeline construction was one of simultaneous scarcity and abundance. Communities directly along the pipeline route, namely Fairbanks and Valdez, were most impacted. In the midst of the biggest resource rush Alaska had ever experienced, with individual salaries at all-time highs, public services were stretched thin and costs soared. Telephone lines were constantly busy as demand overwhelmed available circuits. The electric utility in Fairbanks stopped interconnecting new meters to avoid more brown outs. Nearly every community resource was limited. Schools, banks, and cities couldn’t keep workers, as they kept leaving for higher paid pipeline work. While pipeline workers and other in-demand professions experienced major wage increases, non-oil workers purchasing power declined as inflation soared.

Alaskans reacted rather defensively to the coming of the pipeline and went so far as to elect an environmentalist governor. “There was some feeling of unease about the coming pipeline in early 1974,” According to former Anchorage Mayor Jack Roderick. Many felt the pipeline was too large for Alaska’s small population and economy.36 Even before the height of construction and social disruption, Alaskans opted for a heterodox political leader to guide them through the boom. In 1974, by a very slim margin, Alaskans elected a republican environmentalist named Jay Hammond. A bearded bush pilot, hunter, and “reluctant politician”, Hammond ran on preserving Alaskan values and renewable natural resources. He had been one of the few Alaskan politicians to oppose the pipeline. Hammond recognized the State had a singular opportunity to save its oil wealth and steer Alaska towards a more sustainable economic future. Hammond called for Alaskans to “slow down and see where we’re going before we begin any new developments.” As the specter of the pipeline loomed, he offered Alaskans a vision of a different kind of future.37

As the election of Hammond highlights, the celebration of Prudhoe Bay and enthusiasm for the pipeline were far from universal. As one journalist reported in 1975, the pipe lengths, staged in Valdez, Fairbanks, and the North Slope, “both excite and revolt” Alaskans. There were always a subset of Alaskans—a vocal minority—who feared what the oil boom would do to Alaska’s political culture, natural resources, and subsistence lifeways. “It seems Alaska isn’t so much in a state of transition as trauma,” Hammond concluded; “Alaska isn’t transitioning, it is transcending from its rather slumberous past and literally leaping into a national and international maelstrom of change.”38 Despite the euphoria of many who rode the boom, there was also a period of mourning amongst many Alaskans and many Americans for what had been lost. Long-time Alaskans called their state, changing rapidly before their eyes, the “lost frontier”.39

Ron Rau, a pipeline worker and free-lance writer, termed it “the taming of Alaska.” He wrote in 1976: “In many ways, the pipeline is like an iceberg. What you see with your eyes is only a fraction of what is really there.” Rau argued the “real threat” to the Alaskan wilderness and down-to-earth lifestyle was “the part of the pipeline you cannot see: the money, the people and, most of all, the boom-town mentality that has permeated Alaskan society—a warm, modern house, a steady job and two snowmobiles in every garage.”40

The celebration of “oil in” in 1977 marked both an end and a new beginning. Because speed was of the essence for the pipeline companies, in just over three years the herculean pipeline project—with all its attendant secondary infrastructures—was completed. “Last Pipe Weld Seals off a Lifestyle”, proclaimed one headline in The Anchorage Times.41 Many Alaskans were happy to see the end of this lifestyle. The social friction caused by the influx of newcomers led to a famous Alaskan bumper sticker: “Happiness is 10,000 Okies going south with a Texan under each arm.” Many southerners working on the pipeline didn’t disagree—their version of the bumper sticker added, “With $20,000 in each pocket.”42

The end of three wild years of inflation, sky-high wages, and exuberance for many Alaskans was also the beginning of a new era for American energy production and Alaska’s burgeoning petrocultural state. The state experienced a brief recession in 1977 as the TAPS workforce demobilized and tens of thousands left the state, but the economy quickly rebounded as world oil prices soared and the State of Alaska earned far more than expected from its oil.43 Departing pipeliners were replaced by newcomers eager to build new modern infrastructure for the state, work in its new hospitals, teach in its schools and universities, and serve as professionals across the state—of course for extremely competitive wages.

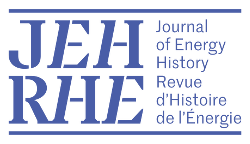

In 1978, a particularly iconic billboard symbolized Alaskans’ angst. Someone spray painted “WHERE WILL IT ALL END?” on the pipeline north of Fairbanks. The message served as reminder of the widespread discontent brought by the pipeline and what many saw as its broad assault on Alaska’s wilderness and traditional lifeways. At the beginning of pipeline operations, some Alaskans were already worried about the end.

From the earliest days of its construction, the pipeline emerged as a cultural and marketing bonanza, as Americans and international visitors were fascinated by the narrative, scale, and controversy of the pipeline. Entrepreneurs sold commemorative kitsch with oil from the first barrel of Arctic crude that moved through the pipeline. Gift shops continue to hawk hats, mugs, and shirts with its serpentine iconography. The pipeline starred in numerous Hollywood films and fictional narratives. Much to environmentalists’ chagrin, the pipeline even became an unlikely tourist destination—even for eco-tours—with “pipeline viewpoints” along Alaska’s highways. In 1983 alone, over half a million people visited the pipeline. Exxon approvingly called TAPS “one of the State’s prime tourist attractions.”44

“The pipeline became the Alaska version of the Seattle Space Needle or the Golden Gate Bridge”, according to Alaska cultural historian David Reamer; “It is visual shorthand for the location.” As Reamer explains, When a Carmen Sandiego villain attacked Alaska in 1991, he HAD to steal the pipeline. “No other monument, building, or location offered the same economic and popular cachet.”45 Indeed, TAPS emerged as the first hydrocarbon pipeline to become an international icon.

The pipeline transformed the built environment of Alaska far beyond its narrow right of way. The skyscrapers of new Alaska Native corporations created out of the pipeline controversy began to dot the skyline of Anchorage. Half of all homes in Alaska today were constructed during the pipeline boom of the early 1970s to the early 1980s.46 Anchorage experienced rapid and largely unplanned growth. “Almost all Americans would recognize Anchorage”, quipped journalist John McPhee, “because Anchorage is that part of any city where the city has burst its seams and extruded Colonel Sanders.”47

While Alaska’s history was dotted with colonial ghost towns from past resource rushes—fur, gold, and copper—astute observers saw a different legacy following the Prudhoe and pipeline boom. Alaskan economist Arlon Tussing predicted that “the rich complex of businesses and professions; schools and churches; clubs, cliques and factions; subcultures and lifestyles that flourished in Alaska during the Prudhoe Bay oil boom of the 1970s and 1980s—and the people who flocked to the state during that period—will not simply vanish in the next few years…”48 For all its precarity, scarcity and abundance, the oil era had brought permanent social changes. The sweeping impact of TAPS would be felt beyond year 2000, predicted journalist James Roscow, who wrote a defining book on the pipeline, “as the state’s vast natural wealth is converted into material affluence and a new social order.”49

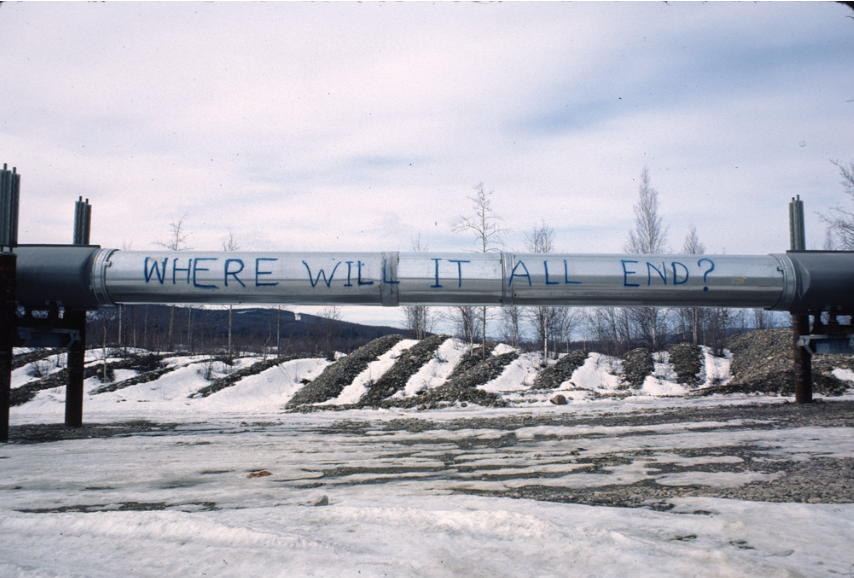

The flow of oil through the pipeline in the late 1970s did not come “at a trickle”, but quickly accelerated to 1.2 million barrels per day.50 Alaskans immediately began to receive a significant oil royalties and tax revenue. The resulting oil wealth only exacerbated growing inequality between Alaska (with its small population) and other states, most of whom were not enjoying a petroleum windfall. In this context, the phrase “Blue-Eyed Arabs” referred to Alaska’s fiscal exceptionalism.51 “Ninety-four percent of all our state revenue is coming down that 48-inch pipe,” explained Alaska state legislator Russ Meekins Jr. in 1980. “Look around,” he implored. “Everything you see we can attribute to the pipeline. The schools we have. The streets that are paved. It’s incredible. We’re living off that thing.”52 No wonder that when the United States’ Postal Service issued a commemorative stamp for the 25th Anniversary of Alaskan Statehood in 1984, they featured the pipeline as a fixture of a mountainous and wild Alaskan landscape.

The wealth flowed to urban and rural Alaska alike. In Anchorage, Alaska’s largest city, oil dollars funded a new convention center, library, and museum. “I can’t imagine Alaska without the pipeline” remarked Diane Brenner of the Anchorage Museum of History and Art in the late 1990s. “The building where I work,” she added, “was built with (oil) money. The government wouldn’t run in this state without pipeline oil money.”53 The influx of new social spending, especially between 1980-1985, remade Alaska’s built environment and the relationship between citizens and the state.

Even more than population booms and the transformation of the built environment, the biggest legacy of the oil boom proved to be the Permanent Fund and Permanent Fund Dividend. As early as the 1930s, Alaskan leaders recognized one way to break the boom-bust cycle of the extractive economy was to save mineral wealth in a state trust fund. Under Governor Hammond, Alaskans amended the Constitution in 1976 to save roughly ten percent of all mineral revenues and royalties in an investment account called the Permanent Fund. While early estimates suggested the Permanent Fund could be as large as 1.3 billion dollars by 1985, the fund amassed 4.3 billion by 1983.54 Governor Hammond then used his considerable political power to create the Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD), whereby roughly half of all earnings from the Permanent Fund were disbursed directly to each Alaskan as a cash dividend each year.

On June 14th, 1982, the State of Alaska mailed out the first PFD check to each Alaskan man, woman, and child for $1,000. Alaska became the first polity of any kind to disburse a sovereign wealth funds earnings directly to citizens, without regard to need.55 In time, the PFD emerged as the state’s most popular policy and became a fixture of Alaskan culture and national perceptions of Alaska. Rather than just a mechanism to protect the principal of the Permanent Fund, as Hammond intended, for many Alaskans the Dividend became an end in itself—the very purpose of the fund. Citizens mistakenly but tellingly referred to getting their “permanent dividend fund” money.

During this same period, Alaskans leaders—including Jay Hammond, to his everlasting regret—voted to repeal the state’s modest income tax. Ten years after the startup of TAPS, the State spent four times as much money per resident as it did in 1977, but collected far less revenues from citizens and non-oil sources.56 Alaskans effectively had negative taxation, as oil wealth paid for government services, citizens received cash payouts from the Permanent Fund, and residents became “disconnected” from state revenue source.57

Back to topDouble Bust (1986-1999)

The heady atmosphere of the late 1970s and early 1980s laid the seeds for a twofold downfall that permanently transformed Alaska’s petroculture. This double bust of the later 1980s stemmed from fiscal instability and an environmental disaster that constituted the single largest failure of TAPS. Both events left a deep wound in the Alaskan psyche and ended the halcyon days of the oil boom.

While some believed the high oil prices and high state spending created in the wake of the 1970s oil crises would continue indefinitely, careful observers knew oil history suggested the opposite: busts always followed booms. The phenomenal growth of state spending in the early 1980s stopped in July 1985. The reversal of state spending had a cascading impact across the economy, bursting the bubble in housing and the heavy construction industry. By April, 1985, Alaska was losing 1,660 jobs per month. Then oil prices began to decline in December 1985. In 1986, Saudi Arabia dramatically increased production, and due to its role as the global swing producer, the bottom fell out of the global oil market. Oil prices fell below ten dollars a barrel and the State responded by further cutting spending, which only intensified job losses.58 State spending cuts hit the state particularly hard, since a quarter of Alaska’s workforce was employed by the state—the highest percentage of any state in the union.59

The collapse of oil prices devastated Alaska’s economy and resulted in economic turmoil that came to be known as, “The Great Alaskan Recession”. Alaska lost more than 20,000 jobs from 1985 to 1987. Due to an over-leveraged real estate sector, fifteen banks went bankrupt or consolidated. The recession got so bad that some Alaskans just left the keys to their financially-underwater houses in the mailbox, dropped their pets off at nearby animal shelters, and left the state. It was the worst recession the history of the State of Alaska.60 By the end of 1987, 14,000 houses in Anchorage sat empty and by the end of the decade there were more than 30,000 foreclosures. Overall, fifteen percent of the population left the state; it was a mass exodus.61 “The Trans-Alaska pipeline fulfilled the wildest dreams we had for the Alaskan economy”, recalled Alaska historian Claus-M. Naske, “but the boom lasted for only a few years”.62

Between 1978 and 1986, Alaska spent more than thirty billion dollars. In the late 1980s, a popular bumper sticker encapsulated public sentiment: “God, please give us another boom. We promise not to piss this one away.”63 Most Americans likely had little empathy for Alaskans, as the state had profited enormously when oil prices were high and other Americans were paying record sums for oil. This is why many referred to Alaskans as “blue-eyed Arabs” who had more in common with sheiks than middle America.64

Paradoxically, while oil prices bottomed out at historic lows, the pipeline pushed more oil than ever before. In 1988, TAPS reached peak throughput at over two million barrels per day, yet Alaskans earned pennies on the dollar for their oil. The high flow of oil meant that the oil terminal at Valdez had to accommodate a record number of supertankers to move the crude to the Lower 48. This moment of TAPS maximum capacity contributed to the worst environmental disaster in Alaska’s history.

On March 24rd, 1989, after departing the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System’s Marine Terminal, the Exxon Valdez supertanker smashed into Bligh Reef in Prince William Sound. Tens of millions of gallons of North Slope crude oil gushed into the pristine waters over the next few days. The spill proved ecological disastrous, killing as many as half a million seabirds, tens of thousands of otters, hundreds of seals, at least 250 bald eagles, and twenty-two whales.65 Images of dead or dying oil-covered birds, seals, and especially sea otters came to symbolize the disaster for most Americans.

The Exxon Valdez disaster provoked a sharp but uneven backlash from Alaskans. Residents were outraged at the devastation and carnage wrought by the spill. While the tanker’s drunk captain, Joseph Hazelwood, received enormous public scorn, Alaskans also blamed the oil companies for their false safety promises and dismal cleanup performance.66 The disaster was particularly devastating for Alaska Natives and fishermen who relied on Prince William Sound for their subsistence and livelihood. “Never in the millennium of our tradition have we thought it possible for the water to die,” Chief Walter Meganack reflected in the wake of the disaster. “It’s too shocking to understand.”67

Paradoxically, the “bust turned into a boom”, according to two Alaskan journalists. While the economy had begun to recover before the Exxon Valdez, the spill injected billions of dollars into the Alaskan economy and fueled a kind of disaster capitalism. “I’ve already said that if Hazelwood runs for governor, and my guys don’t vote for him,” a Fairbanks welding shop owner told a reporter in 1989, “I’m going to fire every one of them. He’s done more for us than any governor we’ve ever had. Too bad it had to happen from such a bad situation.”68 With the construction of TAPS, Alaska had become a company town. Even when the oil industry was public enemy number one, it remained the economic engine of the state.

Years after the spill, its cultural legacy remained vexed and deeply contested. In 1995, three Brooklyn-based graffiti artists painted a mural in downtown Fairbanks. While the Chief of Police had consented to a mural and instructed the artists he depict mountains, wildlife, and Alaskan pioneers, the group had their own perception of Alaska. “We painted a pipeline that started with a shiesty character holding a fist full of money, the pipeline going down the wall, finally opening up with oil spelling our names,” recalled the artist PMER. “We threw in a bloody cross that said “Valdez” and gave him a mountain.”69 While Alaskans wanted to see themselves as pioneers living amidst a scenic wilderness, outside observers had a different view.

Many local residents reacted with horror to the outsider’s depiction of Alaska. The local Fairbanks Daily News-Miner proclaimed, “Ghoulish mural gives neighbors a chill”. While the mural offered a cutting social criticism of Alaska’s petroculture, local residents—which included a senior citizens home across the street—found it “awful”. The Alyeska Pipeline Service Company was “offended” by the mural’s depiction of Alaska, and promised a swift cleanup.70

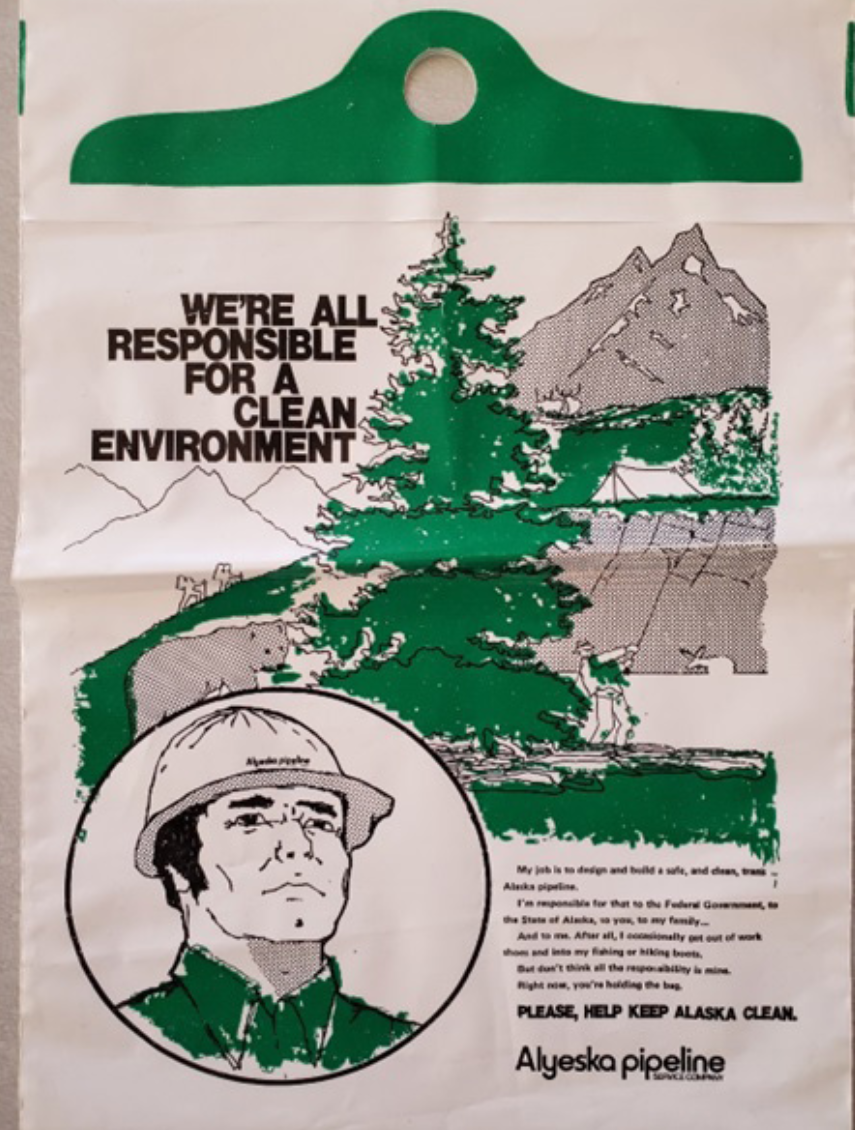

Following the Exxon Valdez, oil industry marketing took on highly visible new marketing campaigns. While the spill was quite clearly Exxon’s fault, the entire Alaskan oil industry and the TAPS system were implicated. Therefore, companies like BP, ARCO, and Alyeska went into overdrive to remind Alaskans of their centrality to the Alaskan way of life. Countless advertisements each week in print, television, and on billboards communicated that oil companies were investing in Alaskan nonprofits, schools, and community programs. The underlying message was clear: Alaskan oil was not simply about money, it was about sustaining an entire culture—an entire way of life.

Perhaps the most visible demonstration of oil company philanthropy emerged in 1990. Following the Exxon Valdez, ARCO Alaska, BP, and Alyeska attempted to rejuvenate their public image by purchasing millions of trash bags for annual public litter cleanups. ARCO first began sponsoring trash cleanup events with bright orange bags. When ARCO was purchased by BP in 1999-2000, the bags then bore BP’s logo. Eventually they became yellow. BP funded these efforts through a community organization called Alaskans for Litter Prevention and Recycling (ALPAR). As the group highlights, “Since 1990, we’ve given away over two million bags to help clean up Alaska.”71 In the wake of the Exxon Valdez, a bright trash bag served as a cultural symbol to Alaskans that oil companies cared about Alaska’s environment. These efforts dovetailed perfectly with famous 1971 Iron Eyes Cody commercial and BP’s “carbon footprint” efforts— endeavors to make individuals feel responsible for systemic environmental impacts.72

Oil companies were extraordinarily invested in rehabilitating their public image. They had spent tens of billions into TAPS and Alaskan oil operations, and needed to expand drilling to maximize profits. It’s no surprise the fight to drill in the Arctic Refuge reached a fever pitch between 1985 and 2005. The intensity over the ANWR battle was directly linked to TAPS, as oil boomers argued that more oil was needed to “fill up” the pipeline and extend its lifespan. Representative Don Young wrote to his fellow Congressmembers in 1987, clarifying that “development of the field can continue to supply the famous Trans-Alaska Pipeline…” According to one source, oil companies were spending as much as 50,000 dollars per week to pay for travel and lodging of teachers and other influential citizens to travel to Prudhoe Bay—in hopes of showcasing the kind of “clean” oil operations that were promised for ANWR.73 It is in this context that George H.W. bush made his remarks about Caribou loving the pipeline and having babies.

Alaska’s Republican congressional delegation and President Reagan’s Secretary of the Interior claimed environmentalists were wrong fifteen years ago when they claimed Prudhoe Bay and TAPS would harm caribou, and he expected similar false claims about harm that would come from drilling in ANWR.74 Alaskan Senator Frank Murkowski explained to President Reagan in 1986 that, “The same groups that opposed to pipeline in 1973 have already mounted an extensive campaign to designate the ANWR coastal plain as wilderness.”75 Murkowski’s timing for this argument could not have been worse. “Twenty years ago, [environmentalists] sounded the same alarm against the Alaska pipeline and they were wrong,” Murkowski argued just three days before Exxon Valdez disaster.76

Ultimately, national public outrage over the Exxon Valdez and organizing by indigenous peoples—namely the Gwich’in peoples of Northeastern Alaska and the Yukon—created widespread political support to oppose oil development in the Refuge during this period.77 Most Alaskans were pro-oil development and favored drilling in the Refuge, but a national campaign convinced most Americans and their elected representatives that ANWR was too special, and oil development too risky, to permit drilling. For decades, TAPS and drilling in Arctic Alaska—especially the controversy over the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge—were powerful symbols in the national fight over energy conservation and development.

Despite the fact that the recent Exxon Valdez oil spill proved the single largest failure of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System, by the mid-1990s TAPS became even more ingrained in the public’s historical imagination. In 1994, the American Society of Civil Engineers named TAPS as one of the Seven Wonders of the United States—along with Hoover Dam, the Golden Gate Bridge, Kennedy Space Center, World Trade Center, Interstate Highway System, and the Panama Canal. In 1997-8, the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History opened a public exhibit on TAPS after Alyeska offered to donate items to the museum. The exhibit coincided with the 20th Anniversary of TAPS. As historian Peter Coates observes, commemorating TAPS as an object of historical memory proved curious, since it was very much an operational system that continued to shape the present and future. While many pipeline critics objected to the exhibit and argued this kind of corporate patronage led to a clearly biased presentation, the Smithsonian had already decided TAPS deserved to be featured in examining the nation’s historical memory.78 In many ways this was a fitting finale for an especially rocky period for TAPS and Alaskan petroculture. Even after contributing to the nation’s worst oil spill, the nation’s flagship history museum celebrated TAPS as a technological marvel.

Back to topArctic Ambivalence (2000-2020)

As Alaska entered the 21st C., the State and its people entered a new petrocultural era of Arctic ambivalence. Following the low oil prices of the late 1980s and 1990s, global oil prices began rising precipitously in the 2000s and hurled Alaska onto a roll coaster of extraordinary price volatility and spasms of paltry and bloated state budgets. The Arctic climate which had molded and defined Alaskan cultures for centuries was now becoming an “angry beast”, in the words of one scientist, with fossil-fueled anthropogenic climate change.79 The pipeline continued to remain central to Alaska’s economy and culture, but ongoing oil dependence left a growing number of Alaskans anxious about the state’s future in a rapidly warming and changing world. Alaskans found themselves the front lines of global climate change—experiencing more wildfires, coastal erosion, and permafrost thaw—yet large numbers of Alaskans remained committed to an extractive hydrocarbon economy.

By the 1990s, scientific studies cleared showed that Alaska and planet’s poles would be particularly affected by climate change. Alaskans were increasingly aware that they were on the front lines of a major climatic shift. Alaskan author Nancy Lord called this early warming.80 And at one time, Alaskans showed some leadership in confronting the issue. Alaska Governor Steve Cowper commissioned a state report in 1990, An Alaskan Response to Global Climate Change.81

By the 2000s, Alaskans—who had historically scoffed at environmentalists’ concerns and sentiments—increasingly worried about climate change as their roads softened with thawing permafrost and mushers feared it was getting too warm for their sled dogs.82 Alaska experienced early snow melt, reduced sea ice, fiercer winter coastal storms, thawing permafrost, droughts and drier landscapes, more pervasive insect outbreaks, and more wildfires. Alaskans began to see the impacts of climate change all around them. Coastal erosion in villages like Shishmaref and Kivalina becoming a major concern, presaging the need to move the community due to rising seas. In 2006, a massive National Science Foundation poll of more than one thousand Alaskans found that eighty-one percent said that global warming was occurring, with fifty-five percent stating that they believed it was caused by human activity, including fossil fuels.83

Many Alaskans argued the State of Alaska was partially to blame for the four degrees Celsius of warming that had already occurred in the last 40 years, since Alaska had pumped billions of barrels of oil. “Unless we do something about the use of fossil fuels,” University of Alaska Professor Gunter Weller argued in 2002, “then the climate impacts will become worse and will be a serious problem.”84

A decade later, while Alaskans continued to see signs of climate change all around them, paradoxically it became even harder for the State to wean itself from fossil fuels. By the 2010s, as a concerted climate denial campaign picked up steam, larger majorities of Alaskans rejected anthropogenic global warming. The fact that some Alaskans also viewed global warming as a favorable trend in frigid Alaska did not help the case for climate action. A few Alaskans even flaunted this view with a bumper sticker: “Alaskans for Global Warming.”85

Mitigating Alaskan carbon emissions also became harder as state revenues dwindled and pro-development Alaskans argued the State needed more oil in the pipeline. Even before the throughput on TAPS peaked in 1988 at over two million barrels per day, petroleum executives and Alaskan politicians increasingly talked of refilling the pipeline.86 This phrase had both economic and technical meanings. “Refilling the pipeline” became shorthand for the need to drill for more oil and bring more revenue to the state. Reflecting all Alaskan Arctic oil production, TAPS experienced a precipitous decline between 1991 and 2001—from an average of 1.8 million to under 1 million barrels per day.87 This economic situation was further compounded by technical issues as the pipeline moved less and less oil. While the pipeline was technically always full, as it moved less oil, which then flowed slower, allowing a greater buildup of wax and ice, which increased costs and reliability issues.88 While there were countless efforts to refill the pipeline in the 2000s—most controversially by drilling in the Arctic Refuge—concerns about the pipeline’s low throughput reached a fever pitch in the 2010s.89

The oil industry used these economic and technical low-flow concerns to push for more drilling, arguing throughput could not decrease below 300,000 b/d. “If [TAPS] were a car,” former Federal Pipeline regulator-turned Alyeska CEO Tom Barrett said, “the ‘add oil’ light would be on.”90 Responding to environmentalists who rejected the idea that the pipeline needed more oil to function properly, Barrett argued that that if environmentalists had gotten their way in the 1970s, “TAPS would never have been built.” In case Alaskans needed reminding about the centrality of the pipeline to their culture, Barrett spelled out that alternative reality: “Billions of dollars for schools, roads, parks and projects would never have touched the state budget; tens of thousands of jobs would never have existed; entire communities would not have flourished and grown; hundreds of Alaska nonprofits wouldn’t have benefited from industry contributions…There would be no [Permanent Fund] dividend.” Barret offered the most succinct oil industry defense of Alaskan petroculture: “The pipeline has changed the nature of our state and the quality of life for Alaskans for the better; sustaining it for decades to come is in the best interest of all of us.”91

Alaskan politicians walked in lock step with Alyeska. “We need to see oil in that pipeline. That’s our cash register,” Alaska’s Governor Bill Walker told reporters in 2017.92 Following the presidential election of Donald Trump, Murkowski and her fellow Alaskan Senator Dan Sullivan quickly put forward a bill to open up ANWR and succeeded in getting mandatory lease sales as part of the 2017 Tax and Jobs Act. Their legislation explicitly cited the increasing challenges from TAPS low throughput and the apocalyptic possibility that the, “Closure of the pipeline would shut down all northern Alaska oil production, devastating Alaska’s economy and deepening U.S. dependence on unstable countries throughout the world.” The solution for the Murkowski, Sullivan, and many other Alaskan politicians was opening the Refuge to drilling and “ensure the pipeline will continue to operate well into the future.”93 Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke supported these efforts and used the pipeline as a cultural touchstone for Arctic drilling. “I put my hand on [the pipeline]”, he said in 2018, “and pledged to help fill it by putting Alaskans back to work on the North Slope.”94

Even more acute than climate for most Alaskans was austerity as state spending declined, state jobs were eliminated, and cuts to social programs spread throughout Alaska. Declining oil revenues, quite simply, caused a social crisis. “You have a state where oil had paid for almost everything”, reflected Alaskan economist Gunnar Knapp in 2017, “and suddenly the oil revenue – most of it — has evaporated.”95

Thanks in large part due to the pipeline population boom and economic expansion of the past thirty years, Alaska’s economy and social institutions were far more mature and diversified than the boom-and-bust decades of the 1970s and 1980s. Yet without state income or sales taxes, Alaska continued to fund its government and social services primarily from oil revenues flowing from TAPS. The oil industry captured the State of Alaska not just politically and economically, but socially and culturally. Yet this capture wasn’t hegemonic: there were always Alaskans fighting for a greater share of oil wealth, fighting to protect native lifeways and subsistence, and fighting for Alaska’s wilderness, biodiversity, and ecological health. By 2020, the pipeline provided far less revenues than it ever had, yet culturally Alaskans were enmeshed as deeply as ever in the petroculture they had created. Paradoxically, Alaskans seem less able to discuss—much less realize—an economy and culture beyond oil. In the 21st C., Alaskans are trapped in the political economy and society they created with the construction of TAPS.

More recently, the effects have climate change have only become even more acute—and no place more so than the villages eroding into the sea. As one report on climate change in the coastal village of Kivalina noted, in 2011 “The rate of climate change is no longer measured in decades, but rather in years, months, or even hours.”96 The pace of change significantly greater than scientists expected. Alaska is no longer warming at twice the rate of the rest of the planet, recent reports claim the region is warming three to four times faster. Ironically, climate change has also particularly affected the TAPS, as permafrost thaw, forest fires, thawing debris lodes, and flooding rivers have threatened pipeline operations.97

TAPS is far from permanent. As Historian Peter Coates observes, it’s the only top modern engineering marvel built with plans for its own removal.98 As part of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Authorization Act, at the end of its economic life, the owners of TAPS are required to dismantle, remove and remediate the pipeline. Currently five billion dollars have been collected for this purpose—but these funds have not been placed in a secure escrow account and these funds may never be made available. It remains to be seen if the oil companies operating TAPS will be financially solvent at that time.99 The end of the pipeline—whether Alaskans have access to the billions they need to dismantle and remediate TAPS—will be another cultural watershed for Alaska. In that regard, it’s worth repeating that question some Alaskans were pondering when the pipeline system first began operating: “WHERE WILL IT ALL END?”

- 1. Colman McCarthy, “Saved in Alaska”, Washington Post, 9 November 1991.

- 2. George H. W. Bush, “Remarks at a Fundraising Luncheon for Senator Frank H. Murkowski”, 11 December 1991, in Gisle Holsbø Eriksen, “From Jimmy Carter to George W. Bush: Presidential Policies and Involvement in the Debate over the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, 1977-2009”(Master thesis, University of Oslo, Oslo, 2009), 67.

- 3. See Robert Redding, The Alaska Pipeline (Chicago: Children’s Press, 1980); Craig Doherty, The Alaska Pipeline, (Woodbridge CT: Blackbirch Press, 1998).

- 4. Campell Gardett, William Hoffman, Jim Palmer, Mike Szymanski, “Taking Stock as TAPS turns 40,” Anchorage Daily News, 27 May 2016.

- 5. Typical environmentalist works include Tom Brown, Oil on Ice: Alaskan Wilderness at the Crossroads (San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1971); Harvey Manning, Cry Crisis! Rehearsal in Alaska (A Case Study of What Government By Oil Did to Alaska and Does to the Earth) (San Francisco: Friends of the Earth, 1974); Michael McCloskey, In the Thick of It: My Life in the Sierra Club (Seattle: Island Press, 2012); Debbie Miller, Midnight Wilderness: Journey’s in Alaska’s National Wildlife Refuge (Braided River, 1990); Riki Ott, Not One Drop: Betrayal and Courage in the Wake of the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill (Chelsea Green Publishing, 2008); David Standlea, Oil, Globalization, and the War for the Arctic Refuge (State University of New York Press, 2006). Booster narratives include John Miller’s Little Did We Know: Financing the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (Cleveland: Arbordale LLC, 2012); Kenneth Harris, The Wildcatter: A Portrait of Robert O. Anderson (New York: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1987); Armand Spielman, Michael D. Travis, The Landmen: How They Secured the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Right-of-Way (Anchorage: Publication Consultants, 2016); H.M. “Ike” Stemmer, South from Prudhoe. (Houston: Universal News Inc, 1977); John Sweet, Discovery at Prudhoe Bay (Surrey, BC: Hancock House Publishers, 2008).

- 6. George Busenberg, Oil and Wilderness in Alaska (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2013); Peter A. Coates, The Trans-Alaska Pipeline Controversy (University of Alaska Press, 1991); John Hanrahan, Peter Gruenstein, Lost Frontier: The Marketing of Alaska (New York: W.W. Norton, 1977); Stephen Haycox, Battleground Alaska: Fighting Federal Power in America’s Last Wilderness (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2016).

- 7. Since Alaska became an oil producer in the late 1950s, TAPS and the North Slope have contributed roughly 18.5 billion barrels, while fields in and around the Cook Inlet have contributed roughly 1.4 billion barrels (2023).

- 8. Peter Coates used evocative term in his essay “The Trans-Alaska Pipeline’s Twentieth Birthday: Commemoration, Celebration, and the Taming of the Silver Snake”, The Public Historian, vol. 23, n° 2, 2001, 63–86.

- 9. Sheena Wilson, Adam Carlson, Imre Szeman, Petrocultures: Oil, Politics, Culture (McGill-Queen’s Press-MQUP, 2017).

- 10. John R. McNeill, Something New Under the Sun: An Environmental History of the Twentieth-Century World (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2000), 298.

- 11. Ross Barrett, Daniel Worden (eds.), Oil Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), xix-xxv.

- 12. Elizabeth Harball, “Alaska’s 40 Years of Oil Riches Almost Never Was”, National Public Radio, 24 June 2017.

- 13. Craig Medred, “Reality Bites”, craigmedred.news, 12/12/ 2019. Url: https://craigmedred.news/2019/12/12/reality-bites/ (accessed 03/06/ 2023).

- 14. For instance, see Joe LaRocca, Alaska Agonistes: The Age of Petroleum, How Big Oil Bought Alaska (North East PA: Rare Books, 2003), 3; Richard B. Wilson, “Severance Taxes, Energy Resources and Blue Eyed Arabs: Is the Power to Tax the Power to Survive?”, 29 (Bureau of Governmental Research and Service, University of Colorado, Boulder, July 1981); One publication used the term to refer to Norway’s demanding offshore leasing regime, Harold Burton Meyers, “Blue-Eyed Arabs Scramble for the Riches of the North Sea,” Fortune, June 1973, 142.

- 15. Tim Bradner, “Where is All Our Oil Money Going?” (Lecture at University of Alaska Anchorage), 9 November 2017.

- 16. Victoria Hermann, “The Birth of Petroleum Path Dependence: Oil Narratives and Development in the North”, American Review of Canadian Studies, vol. 49, n° 2, 303.

- 17. Todd Moss, The Governor’s Solution: How Alaska’s Oil Dividend Could Work in Iraq and Other Oil-Rich Countries (Brookings Institution Press, 2013), 52.

- 18. Harball, “Alaska’s 40 Years of Oil Riches Almost Never Was”, National Public Radio, 14 June 2017.

- 19. Eben Hopsen, “On the Experience of the Arctic Slope Inupiat with Oil and Gas Development in the Arctic”, ebenhopson.com, 1976. Url: http://ebenhopson.com/the-berger-speech/ (accessed 03/06/ 2023).

- 20. Chris Allan, “The Brief Life and Strange Times of the Hickel Highway: Alaska’s First Arctic Haul Road”, Alaska History, vol. 24, n° 2, 2009, 2-29.

- 21. Stanton H. Patty, “Court Ruling on Alaska Indians’ Claims May be Crucial to Pipeline Development”, Seattle Times, 7 April 1970.

- 22. Donald Mitchell, Take My Land, Take My Life: The Story of Congress’s Historic Settlement of Alaska Native Land Claims, 1960-1971 (University of Alaska Press, 2001), 330.

- 23. Jim Kowalsky, interviewed by Philip Wight. Fairbanks, Alaska, 26 September 2017.

- 24. Mitchell, Take My Land, Take My Life, 517 (cf. note 22).

- 25. Stanton Patty, “Busy Senator takes time to ease fears of children in Ohio”, Seattle Times, 15 October 1970, A13.

- 26. “Zero Population Growth deceptively radical idea”, Seattle Times, 14 February 1971, E8.

- 27. “An Act to Amend section 28 of the mineral leasing Act of 1920, and to Authorize a trans-Alaska oil pipeline, and for other purposes”, Public Law 93-153, 16 November 1973.

- 28. Edward J. Fortier, “Alaska Pays the Pipers”, The National Observer, 20 September 1975.

- 29. Alaska Economic Trends, December 1999, 10.

- 30. Georgia Paige Welch, “Right-of-Way: Equal Employment Opportunity on the Trans Alaska Oil Pipeline, 1968-1977” (Ph.D diss., Duke University, Durham, 2015).

- 31. Dermot Cole, Amazing Pipeline Stories: How Building the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Transformed Life in America’s Last Frontier (Epicenter Press (WA), 1997), 38.

- 32. K. L. Marshall, Faith and Oil: How the Alaska Pipeline Shaped America’s Religious Right (Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2020).

- 33. Edward J. Fortier, “Alaska Pays the Pipers” (cf. note 28).

- 34. Naomi Klouda, “Like 80s Recession, net migration turns negative”, Alaska Journal of Commerce, 17 May 2017.

- 35. Cole, Amazing Pipeline Stories, 12 (cf. note 31).

- 36. Jack Roderick, Crude Dreams: A Personal History of Oil & Politics in Alaska (Seattle and Fairbanks: Epicenter Press, 1997), 387.

- 37. Ibid., 390.

- 38. Edward J. Fortier, “Alaska Pays the Pipers” (cf. note 28).

- 39. John Hanrahan, Peter Gruenstein, Lost Frontier: The Marketing of Alaska (New York: W.W. Norton, 1977).

- 40. Ron Rau, “The Taming of Alaska,” National Wildlife, October-November 1976, 19–20.

- 41. Mike Kennedy, “Last Pipe Weld Seals Off a Lifestyle”, Anchorage Times, 5 June 1977.

- 42. Cole, Amazing Pipeline Stories, 58 (cf. note 31).

- 43. Gregg Erikson, Mitt Barker, “The Great Alaska Recession”, Erikson & Associates, 12/05/2015. Url: https://www.alaskapublic.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Erickson150412-… (accessed 20/03/2023).

- 44. Walter K. Wilson, “Taps revisited”, The Lamp, Fall 1984.

- 45. David Reamer (@ANC_Historian) tweet, 2022.

- 46. Casey Kelly, “That 70s Home: How AHFC is Trying to Update Alaska’s Aging Housing Supply”, KTOO, 19 March 2015.

- 47. John McPhee, Coming Into the Country (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1976), 130.

- 48. Arlon R. Tussing, “Alaska’s Petroleum-Based Economy,” in Thomas Morehouse (ed.), Alaskan Resources Development: Issues of the 1980s (Routledge, 2019), 74.

- 49. James Roscow, “James Roscow talked to Alaskans About those changes. This is what he found.” Alyeska Reports, 1975.

- 50. Sen. Henry Jackson, “Alaska Oil Development: International and Local Implications” (World Trade Club of Seattle: Seattle WA, 1969), 6,13

- 51. Charles McClure Jr., “The Taxation of Natural Resources and the Future of the Russian Federation”, Environment and Planning, vol. 12, n°3, 1994, 309-318.

- 52. Robert Atwood, “Pipeline Editorial”, The Anchorage Times, 1980.

- 53. Coates, “The Trans-Alaska Pipeline’s Twentieth Birthday”, 65 (cf. note 8).

- 54. Dermot Cole, “40 years of writing about the Permanent Fund and its place in Alaska”, Anchorage Daily News, 2017.

- 55. David A. Rose, Saving for the Future: My Life and the Alaska Permanent Fund (Epicenter Press, 2008).

- 56. James Fallows, “Nigeria of the North”, The Atlantic, 1 August 1984.

- 57. For the Alaska Disconnect, see Mike Navarre, “Fixing the Alaska Disconnect”, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, 6 April 2017.

- 58. Gregg Erikson, Mitt Barker, “The Great Alaska Recession”, Alaska Public Media, 12 April 2015.

- 59. William S. Brown and Clive S. Thomas, “The Alaska Permanent Fund: Good Sense or Political Expediency?”, Challenge, vol. 37, n° 5, 1994, 39.

- 60. Erikson, Barker, “The Great Alaska Recession” (cf. note 43).

- 61. Alaska Economic Trends Magazine, December 1999, 17.

- 62. “Alaska: 25 Years of Statehood”, CQ Researcher, 9 December 1983.

- 63. Amanda Coyne, Tony Hopfinger, Crude Awakening: Money, Mavericks, and Mayhem in Alaska (Bold Type Books, 2011), 43.

- 64. William S. Brown, Clive S. Thomas, “The Alaska Permanent Fund: Good Sense or Political Expediency?”, Challenge, vol. 37, n° 5, 1994, 40.

- 65. Melissa Bert, John Chaddic, “The Arctic in Transition—A Call to Action,” Journal of Maritime Law and Commerce, vol. 40, n° 4, 2009, 481.

- 66. Art Davidson, In The Wake of the Exxon Valdez: The Devastating Impact of the Alaska Oil Spill (San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1990).

- 67. Duane A. Gill, J. Steven Picou, “The Day the Water Died: The Exxon Valdez Disaster and Indigenous Culture”, in Steven Biel (ed.), American Disasters (New York University Press, 2001), 277-301.

- 68. Coyne, Hopfinger, Crude Awakening, 58 (cf. note 63).

- 69. PMER/ Catellovision, “Flashback to ’95: PMER, REVS and FUEL in Alaska”, blog.vandalog.com. Url: https://blog.vandalog.com/2013/05/27/flashback-to-95-pmer-revs-and-fuel… (accessed 25/11/ 2022).

- 70. Brian Donoghue, “Ghoulish mural gives neighbors a chill”, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, 16 July 1995.

- 71. “ALPAR Programs”, alparalaska.com. Url: https://www.alparalaska.com/wp/programs/ (accessed 25/11/2022).

- 72. Finis Dunaway, Seeing Green: The Use and Abuse of American Environmental Images (University of Chicago Press, 2015).

- 73. “The Valdez Spill: What will its legacy be?”, Audubon Magazine, November/ December 1989.

- 74. Don Young to all Congressmen, 22 January 1987. Ronald Reagan Presidential Library; Congressional Quarterly, 22 August 1987, “Alaskan Wildlife Refuge Becomes Battleground”.

- 75. Frank Murkowski to Ronald Reagan, 17 December 1986.

- 76. Henrik Hertzberg, “That’s Oil, Folks”, The New Republic, 23 April 1989.

- 77. Finis Dunaway, Defending the Arctic Refuge: A Photographer, an Indigenous Nation, and a Fight for Environmental Justice (UNC Press Books, 2021).

- 78. Coates, “The Trans-Alaska Pipeline's Twentieth Birthday”, 65-66 (cf. note 8).

- 79. Spencer Weart, The Discovery of Global Warming (Harvard University Press, 2008), 59.

- 80. Nancy Lord, Early Warming: Crisis and Response in the Climate-Changed North (Berkeley CA: Counterpoint Press, 2011).

- 81. Steffan, Greenlaw et al., “Alaska’s Climate Change Policy Development” (Center for Arctic Policy Studies, 2021).

- 82. Spencer R. Weart, The Discovery of Global Warming (Harvard University Press, 2008).

- 83. Michael Carey, “Alaska Melting”, Dissent, Fall 2015.

- 84. Alex Kirby, “Alaska’s Oil ‘melts its ice’”, BBC News, 7 May 2002.

- 85. Nancy Lord, Early Warming, 14-15 (cf. note 80).

- 86. See, for instance, Rep. Don Young to members of Congress, 22 January 1987, Ronald Reagan Library.

- 87. Historic TAPS throughput, https://www.alyeska-pipe.com/historic-throughput/.

- 88. Mohamed A. Abdel-Rahman, “Resource Plays Could Help Refill Trans-Alaska Pipeline,” Oil & Gas Journal, vol. 111, n° 1, 2013.

- 89. Philip Wight, “How the Alaska Pipeline Is Fueling the Push to Drill in the Arctic Refuge”, Yale Environment 360, 16 November 2017.

- 90. Kevin Baird, “Trans-Alaska Oil Pipeline Celebrates 40th Anniversary”, US News and World Reports, 24 June 2017.

- 91. Tom Barrett, “Commentary on pipeline oil flow is flat wrong”, Anchorage Daily News, 11 November 2016.

- 92. Alex Nussbaum, “A pipeline built to survive extremes can’t bear slow oil flow,” Bloomberg, 11 April 2017.

- 93. “Murkowski, Sullivan Introduce Bill to Allow Energy Production in 1002 Area of Arctic Coastal Plain”, US Senate Press Release, 05/01/2017. Url: https://www.energy.senate.gov/2017/1/murkowski-sullivan-introduce-bill-… (accessed 20/03/ 2023).

- 94. Julie St. Louis, “Environmentalists Sue to Block Alaska Oil Leases”, Courthouse News Service, 02/02/2018. Url: https://www.courthousenews.com/environmentalists-sue-to-block-alaska-oi…(accessed 20/03/ 2023).

- 95. Elizabeth Harball, “Alaska’s 40 Years of Oil Riches Almost Never Was”, National Public Radio, 24 June 2017.

- 96. “Climate Change in Kivalina, Alaska: Strategies for Community Health”, Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, 2011, 5.

- 97. David Hasemyer, “Raging Flood Waters Driven By Climate Change Threaten Trans-Alaska Pipeline”, Inside Climate News, 12 October 2021.

- 98. Peter Coates, “The Trans-Alaska Pipeline's Twentieth Birthday: Commemoration, Celebration, and the Taming of the Silver Snake” (cf. note 8).

- 99. Richard Fineberg, “Trans-Alaska Pipeline System Dismantling, Removal, and Restoration (DR&R): Background Report and Recommendations,” Anchorage, AK: Prince William Sound Regional Citizens’ Advisory Council, 2004.

Archival and Primary Sources

Atwood Robert, “Pipeline Editorial”, The Anchorage Times, 1980.

Baird Kevin, “Trans-Alaska Oil Pipeline Celebrates 40th Anniversary”, US News and World Reports, 24 June 2017.

Barrett Tom, “Commentary on pipeline oil flow is flat wrong”, Anchorage Daily News, 11 November 2016.

Carey Michael, “Alaska Melting”, Dissent, Fall 2015.

Donoghue Brian, “Ghoulish mural gives neighbors a chill”, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, 16 July 1995.

Fallows James, “Nigeria of the North”, The Atlantic, 1 August 1984.

Fortier Edward J., “Alaska Pays the Pipers”, The National Observer, 20 September 1975.

Hopsen Eben, “On the Experience of the Arctic Slope Inupiat with Oil and Gas Development in the Arctic”, ebenhopson.com, 1976. Url: http://ebenhopson.com/the-berger-speech/ (accessed 03/06/2023).

Jackson Henry, “Alaska Oil Development: International and Local Implications” (World Trade Club of Seattle: Seattle WA, 1969).

Kennedy Mike, “Last Pipe Weld Seals Off a Lifestyle”, Anchorage Times, 5 June 1977.

Kirby Alex, “Alaska’s Oil ‘melts its ice’”, BBC News, 7 May 2002.

Kowalsky Jim, interviewed by Philip Wight, Fairbanks, Alaska, 26 September 2017.

McCarthy Colman, “Saved in Alaska”, Washington Post, 9 November 1991.

Meyers Harold Burton, “Blue-Eyed Arabs Scramble for the Riches of the North Sea,” Fortune, June 1973, 140-145.

Murkowski, Sullivan, Introduce Bill to Allow Energy Production in 1002 Area of Arctic Coastal Plain”, US Senate Press Release, 05/01/2017. Url: https://www.energy.senate.gov/2017/1/murkowski-sullivan-introduce-bill-… (accessed 20/03/2023).

Navarre Mike, “Fixing the Alaska Disconnect”, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, 6 May 2017.

Nussbaum Alex, “A pipeline built to survive extremes can’t bear slow oil flow,” Bloomberg, 11 May 2017.

Patty Stanton H., “Court Ruling on Alaska Indians’ Claims May be Crucial to Pipeline Development”, Seattle Times, 7 May 1970.

Patty Stanton H., “Busy Senator takes time to ease fears of children in Ohio”, Seattle Times, 15 October 1970, A13.

PMER/ Catellovision, “Flashback to ’95: PMER, REVS and FUEL in Alaska”, blog.vandalog.com. Url: https://blog.vandalog.com/2013/05/27/flashback-to-95-pmer-revs-and-fuel… (accessed 25/11/2022).

Rau Ron, “The Taming of Alaska,” National Wildlife, October-November 1976, 19–20.

Roscow James, “James Roscow talked to Alaskans About those changes. This is what he found.”, Alyeska Reports, 1975.

St. Louis Julie, “Environmentalists Sue to Block Alaska Oil Leases”, Courthouse News Service, 02/02/2018. Url: https://www.courthousenews.com/environmentalists-sue-to-block-alaska-oi…(accessed 20/03/ 2023).

Wilson Walter K., “Taps revisited”, The Lamp, Fall 1984.

Secondary Sources

Abdel-Rahman Mohamed A.n “Resource Plays Could Help Refill Trans-Alaska Pipeline”, Oil & Gas Journal, vol. 111, n° 1, 2013.

Allan Chris, “The Brief Life and Strange Times of the Hickel Highway: Alaska’s First Arctic Haul Road”, Alaska History, vol. 24, n° 2, 2009, 2-29.

Baker Rachel, Boucher John, Fried Neal, Windisch-Cole Brigitta, “Long-Term Retrospective: Alaska’s Economy Since Statehood”, Alaska Economic Trends, vol. 19, n° 12, 1999, 3-21.

Barrett Ross, Worden Daniel (eds.), Oil Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014).

Bert Melissa, Chaddic John, “The Arctic in Transition-A Call to Action”, Journal of Maritime Law and Commerce, vol. 40, n° 4, 2009, 481-509.

Bradner Tim, “Where is All Our Oil Money Going?” (Lecture at University of Alaska Anchorage), 9 November 2017.

Brown Tom, Oil on Ice: Alaskan Wilderness at the Crossroads (San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1971).

Brown William S., Thomas Clive S., “The Alaska Permanent Fund: Good Sense or Political Expediency?”, Challenge, vol. 37, n° 5, 1994, 38-44.

Brubaker Michael, Berner James, Bell Jacob, Warren John, “Climate Change in Kivalina, Alaska: Strategies for Community Health” (Anchorage, AK: Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, 2011).

Busenberg George, Oil and Wilderness in Alaska (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2013).

Coates Peter, “The Trans-Alaska Pipeline’s Twentieth Birthday: Commemoration, Celebration, and the Taming of the Silver Snake”, The Public Historian, vol. 23, n° 2, 2001, 63–86.

Cole Dermot, Amazing Pipeline Stories: How Building the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Transformed Life in America’s Last Frontier (WA: Epicenter Press,1997).

Cole Dermot, “40 years of writing about the Permanent Fund and its place in Alaska”, Anchorage Daily News, 02/09/2017. Url: https://www.adn.com/opinions/2017/09/02/40-years-of-writing-about-the-p… (accessed 12/05/2023)

Cole Terrence, Fighting for the Forty-Ninth Star: CW Snedden and the Crusade for Alaska Statehood (University of Alaska Press, 2010).

Cooper Bryan, Alaska: The Last Frontier (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1973).

Coyne Amanda, Hopfinger Tony, Crude Awakening: Money, Mavericks, and Mayhem in Alaska, (Bold Type Books, 2011).

Davidson Art, In The Wake of the Exxon Valdez: The Devastating Impact of the Alaska Oil Spill (San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1990).

Doherty Craig, The Alaska Pipeline (Woodbridge CT: Blackbirch Press, 1998).

Dunaway Finis, Defending the Arctic Refuge: A Photographer, an Indigenous Nation, and a Fight for Environmental Justice (Chapel Hill: UNC Press Books, 2021).

Eriksen Gisle Holsbø, “From Jimmy Carter to George W. Bush: Presidential Policies and Involvement in the Debate over the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, 1977-2009” (Master Thesis, University of Oslo, 2009).

Erikson Gregg, Barker Mitt, “The Great Alaska Recession”, Alaska Public Media, 12/4/2015. Url: https://www.alaskapublic.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Erickson150412-… (accessed 20/03/2023)

Fineberg Richard, “Trans-Alaska Pipeline System Dismantling, Removal, and Restoration (DR&R): Background Report and Recommendations” (Anchorage: Prince William Sound Regional Citizens’ Advisory Council, 2004).

Gill Duane A., Picou J. Steven, “The Day the Water Died: The Exxon Valdez Disaster and Indigenous Culture”, in Steven Biel (ed.), American Disasters (New York: New York University Press, 2001), 277-301.

Gardett Campell, Hoffman William, Palmer Jim, Szymanski Mike, “Taking Stock as TAPS turns 40,” Anchorage Daily News, 27/05/2016. Url: https://www.adn.com/opinions/2017/05/27/taking-stock-as-taps-turns-40/ (accessed 10/05/2022).

Hasemyer David, “Raging Flood Waters Driven By Climate Change Threaten Trans-Alaska Pipeline”, Inside Climate News, 12/10/ 2021. Url: https://insideclimatenews.org/news/12102021/trans-alaska-pipeline-clima… (accessed 02/15/2022)

Harball Elizabeth, “Alaska’s 40 Years of Oil Riches Almost Never Was”, National Public Radio, 24/06/2017. Url: https://www.npr.org/2017/06/24/533798430/alaskas-40-years-of-oil-riches… (accessed 10/18/2022).

Harris Kenneth, The Wildcatter: A Portrait of Robert O. Anderson (New York: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1987).

Hanrahan John, Gruenstein Peter, Lost Frontier: The Marketing of Alaska (New York: W.W. Norton, 1977).

Haycox Stephen, Battleground Alaska: Fighting Federal Power in America’s Last Wilderness, (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2016).

Herrmann Victoria, “The Birth of Petroleum Path Dependence: Oil Narratives and Development in the North”, American Review of Canadian Studies, vol. 49, n° 2, 2019, 301–31.