Dark futures: the loss of night in the contemporary city?

ImaginationLancaster, Lancaster University

The artificial but widely held binary conceptions of day versus night find themselves condensed in cities where strategies to recalibrate the nocturnal urban landscape are abundant. This transformation requires considerable energies and technologies to facilitate illumination. The night-time city remains poorly understood, requiring new inquiries to examine the tensions and coexistences of light and darkness. This article examines the city of Manchester, United Kingdom, its pioneering history of industrialisation, and subsequent phases of regeneration and gentrification to explore its contemporary urban landscape. It draws on extensive autoethnography of experiences in the city to consider the potential of different lights and darknesses for how we might think more holistically with regard illumination, and the reciprocity between our senses and the urban environment.

Plan de l'article

- Introduction. Reconsidering darkness and light

- Energy history and urban illumination in the first industrial city

- Gloomy landscapes and an architecture of darkness

- Patchwork infrastructures, blackouts and post-war reconstruction

- Recent development and the desire for increased urban lighting

- Walking in the city after dark

- Understanding the diversity and coexistences of darkness

Introduction. Reconsidering darkness and light

Threaded down along the river, a rich vein of memento mori for the city. The fuzz of distant light bobbles along the water’s surface. The Irk, like the night, has a history of uneven tempo, once renowned for its speed then later akin to a large slug such was its apparent inertia. Onward and across Angel Meadows, a subplot for the district, solemnly resists further development of the next instalment of Manchester’s rejuvenation program. The turf here quietly bridling with the mass grave of industrial past, the interned some of whom were overturned as poverty led to the digging up of cemetery soil for sale as fertilizer for nearby farmers. Looming ahead the globular spaceship of the Co-operative headquarters nestles into the urban warp and weft around it. Rochdale Road, a discreet fissure between pallid gentrification and bodged cosmetic surgery of renewal, strikes ahead, forging away from the city centre: an echo chamber of recurrent hopes and scuffed dreams. Tonight is cold in the lungs, the air turning them to brittle chambers that with each inhalation feel as though they might shatter. Crisp footsteps and the plumes of hydrated air accompany my perambulations. Dull metal-grey mini-submarines, discharged of gas for their hysteria, litter the doorway of an old mill. The laughing and jostling shadow forms having long moved onto another urban cove. The ramparts of the city’s innards pulp here, yielding to exigencies of conflicting needs and desires.

Colourful illuminations of the music venue’s façade count out the pulse. Disconnected from the audio inputs of the city or the music venue itself when open, the ultimate silent disco. But the city is not still nor without noise. The cacophony of drinkers, clubbers and taxis may be gone but the hum of distant traffic is still legible. Closer by a feline-eyed shadow leaps onto the wall of the Smithfield Gardens housing estate. Once another compost heap for humanity, the dispossessed deported to the outer suburbs, its replacement of orange-red maisonettes work on their own internal logic. Tib Street, the menagerie of birds and animals displayed along this bone of the city gone too. Dispensed between the stubbed side streets and poured onto Oldham Street. This road used to witness the parading of people in their Sunday best, consuming the stores' windows and eyeing up each other. Strict moral codes, ladies on one side, gentlemen on the other. Tonight though, the only attention coming my way is from a drained, rattling can, its energy-drink contents seemingly not giving up the ghost just yet.

The opening section of this article is an extract from a description of a night-time walk I took in early 2014. Over the last five years I have spent many hundreds, if not thousands, of hours walking through various cities at night, interested in how my physical and psychological relationships with the built environment change amongst different lights and darknesses. Clearly, this set of experiences has led to a very particular and personal view. However, this is to be considered as a contribution toward what has been recently argued as an urgent need for both a plurality and diversity of perspectives regarding darknesses1, how different experiences of place and time may contribute to our understanding of them2, and the effects of light pollution.3 From a historical perspective, the coexistence between light and darkness has been thoughtfully examined by Ekirch4, whilst the different relationships of various communities, groups and movements and their cultural entanglements with darkness has been comprehensively discussed by Palmer.5 Accompanying these accounts have been inquiries into the nature of darkness and its conceptual framing as being in opposition to light. This apparent antithetical relationship has led to darkness being bound up in powerful metaphorical relationships and moral implications. As Dunnett explicates, “the idea of light, both in a practical and symbolic sense, has come to be associated with modernisation and the so-called ‘Enlightenment project’ in various different ways… Here we can also see how the metaphor of light has taken on a moralising tone, seen as an all-encompassing force for good, banishing the ignorance of darkness in modern society.”6 However, this binary narrative has not gone unchallenged and the significant diversity in light and shadow has been the subject of different investigations that suggest a counter-history of the importance of dark places.7

In specific reference to night-time lighting, Schivelbusch observes that perceptions of it throughout history have consistently merged the literal and symbolic8, whilst Schlör points directly to the dominance of light over darkness in considering the urban night, “[o]ur image of night in the big cities is oddly enough determined by what the historians of lighting say about light. Only with artificial light, they tell us, do the contours of the nocturnal city emerge: the city is characterized by light.”9 Yet the importance of penumbra and shadow in the Western arts and imagination across numerous artistic and literary traditions has enabled the multiple variations of light and dark to be reconsidered.10 It has also been demonstrated by Sharpe that the spatiality and physicality of urban darkness amidst the burgeoning development of artificial lighting technologies directly influenced numerous artistic interpretations of the urban night.11 Perhaps unsurprisingly, many of these accounts are dominated by male figures or collectives given the purview of the relationship between women and the night-time which was maintained throughout history and to various extents remains, depending on cultural differences, religious beliefs, and other social factors. The diversity of darknesses and experiences of them is notable despite a common tendency to think of the modern night as a consistent space and time, as Williams reminds us, “[n]ight spaces are neither uniform nor homogenous. Rather they are constituted by social struggles about what should and should not happen in certain places during the dark of night.”12 In the contemporary context, there has been important shifts in the accessibility and safety for a wider spectrum of different ages, genders, races and sexual orientations through movements and organisations such as Reclaim the Night13 and Take Back the Night.14 This has led to a more inclusive and tolerant attitude toward different communities and groups, signalling the major progresses that occurred during the 20thC from widely demonised and prohibited activities, through necessary covert and codified behaviour, to more equal rights and less discrimination in the present day. It is important to recognise, however, that this is an ongoing process far from complete. Such developments have been paralleled by a history of the different forms of experience and places that LGBTQ+ communities have accessed, created, and sustained to provide, wherever possible, an enjoyable, vibrant and safe urban night.15 Walking, especially at night, may be understood to have multiple interpretations attached to it, since it is typically constructed through cultural, economic, political, and/or social interrelationships. For the purpose of this article, I will focus on how it enables architecture and spatial boundaries to be sensed differently in direct reference to the quality and quantity of illumination available, energy manifest in the urban landscape.

Architecture is typically understood as the material, sometimes literally concrete, facts of the built environment. Its presence and function reflect the values of the society that produced it. However, no matter how stable our buildings may appear they are constantly changing, inside and outside, through the effects of weather, occupation, ageing, and, of course, lighting and darkness. With regard the latter, light-pollution scientists amongst others have demonstrated that lighting is not about ‘pure’ numbers and it is evident that the reflective quality of surfaces, including those in the built environment16, and weather conditions can have a significant impact on the quantity and quality of light and, by extension, darkness.17 The context for this exploration is the city of Manchester, and the adjacent city of Salford, for several reasons. First and foremost, they have a considerable history relating to lights and darknesses, Manchester not least in relation to its pioneering role in the industrialisation of cities. Secondly, the subsequent phases of regeneration and gentrification that the former has undergone have produced a contemporary urban landscape of considerable diversity in terms of illumination. Thirdly, Manchester announced in 2014 that it would commence the replacement of its city-wide 56,000 lamps with LED lights thus changing the appearance of its lights and darkness for the foreseeable future.18 Finally, as my home city and its neighbour, and the ones with which I am most familiar, I have been able to conduct my autoethnographic and experimental fieldwork frequently and in a practical manner. This fourth aspect has proved particularly important. Given the social construction of time and work, it would have been difficult to repeatedly travel significant distances on a very frequent basis in order to examine different conditions and situations for their lights and darknesses. My fieldwork has necessarily been conducted using mobile methods and often in an ad-hoc manner, so it could integrate within my life both fully yet also be as improvisational as possible.

Back to topEnergy history and urban illumination in the first industrial city

In order that we can appreciate the contemporary situation, we will first trace out some of the key developments in the city’s history with regard its complex relationships between light and darkness. The transformation from a market town to an increasingly congested and expanding centre is recorded by Wheeler who notes in this rapidly changing landscape new forms of experience were produced such as the passage between St. Ann’s Square and the Market Place that “was appropriately designated as the Dark Entry.”19 As the crucible for the Industrial Revolution, Manchester has been widely recognised as the world’s first industrial city growing as it did from a market town with a population of less than 10,000 at the beginning of the 18th C. to a population of 89,000 by the end of the century. The boom in population continued in the 19th C., doubling between 1801 and the 1820s, only to double again before 1851, amassing a total population of 400,000 people. This was phenomenal growth by any standard, transforming Manchester into Britain’s second city. Perhaps unsurprisingly, such population growth brought with it extremely poor and dense living conditions for many of the city’s inhabitants. A crucial driver to this population explosion was the opportunities for work. Unlike agricultural workers whose days were dictated by the availability of daylight and therefore limited in the dark winter months or very bad weather, factory workers could work every hour due to the use of artificial lighting and the technological advancements in mill machinery. In 1798, George and Adam Murray completed the first phase of their steam-powered urban cotton mill in Ancoats, the first suburb to integrate housing and industry.20 When completed in 1806, the complex housed two separate cotton spinning mills, two warehouses, preparation and office ranges, all arranged around a central quadrangle. The importance of the Murrays’ Mills development was evident with visitors travelling from the rest of the UK, Europe and the US to witness the huge complex, housing powered machinery and illuminated by gas.

Parallel to this development in the adjacent town of Salford, the first gas street lighting in world illuminated part of Chapel Street and the Philips and Lee Factory. This deployment of lighting technology was to transform the world as it was then known since it transferred and reframed the ‘working day’ to a non-stop, continually functioning place where the previous relationship between labour and time were shattered. Through his discussion of Arkwright’s Cotton Mills by Night painted by Joseph Wright of Derby circa 1782, Jonathan Crary makes clear that it is not simply the unusual sight of a large brick building within a countryside setting that makes the image so strange. In addition, he identifies, “most unsettling, however, is the elaboration of a nocturnal scene in which the light of a full moon illuminating a cloud-filled sky coexists with the pin-points of windows lit by gas lamps in cotton mills.”21 For it is here that the artificial lighting of the factories announces its victory over the long-held light-dark cycle and circadian rhythms that had previously connected time and work. Pivotal to this endless labour was of course the need for constant energy production to power its machinery. The use of coal was essential to this process with all the attendant environmental and health hazards that contributed to significant commentators of the period such as the historian Thomas Carlyle decrying the condition of England and using “Sooty Manchester” which was “every whit as wonderful, as fearful, unimaginable, as the oldest Salem or Prophetic City”22 as testament. Meanwhile, the squalid and dark landscapes that the industrialised city created provided fertile ground for numerous writers including Benjamin Disraeli, Elizabeth Gaskell and Charles Dickens, the latter creating ‘Coketown’ in Hard Times23 as the very epitome of human misery within soot-covered brick buildings.

Back to topGloomy landscapes and an architecture of darkness

There is an interesting point to be made here about the impact of energy production upon the light and darkness of its surrounding context. The soot produced by the coal burning furnaces to power the machinery around them was airborne and quickly built up on the surfaces of the buildings across the city. As Alexis de Tocqueville when visiting Manchester in 1835 reported, “[a] sort of black smoke covers the city. The sun seen through it is a disc without rays. Under this half-daylight 300,000 human beings are ceaselessly at work. A thousand noises disturb this dark, damp labyrinth, but they are not at all the ordinary sounds one hears in great cities.”24 Within his account of his seven-day trip to the city, de Tocqueville relates the extremes of the Manchester experience and the paradox that lay at the heart of its industrial success. This reminds us that in addition to the numerous forms in which the development of lighting technologies transformed people’s perception of the world in spatialized ways through cultural, social, and political dimensions, not least with regard labour25, the process of industrialisation also resulted in direct and significant shifts in the natural light of such contexts. Between 1842 and 1844, Manchester was to have another visitor in the form of Friedrich Engels who drew upon his time living in the city for his book, The Condition of the Working Class in England. Two local young women, Mary and Lizzy Burns accompanied Engels to enable him to gain access to wander the slums and ensure his safety. Engels’ depiction of the “Hell upon Earth” amidst the coal-powered industry is vivid and haunting,“[s]uch is the Old Town of Manchester, and on re-reading my description, I am forced to admit that instead of being exaggerated, it is far from black enough to convey a true impression of the filth, ruin, and uninhabitableness, the defiance of all considerations of cleanliness, ventilation, and health which characterise the construction of this single district, containing at least twenty to thirty thousand inhabitants.”26

The experiences of light and darkness in Manchester during this period were evidently grim. Indeed, the traces of the squalid, dirty and dangerous character of some of its inner-city areas lives on through the surviving nomenclature of Dark Lane and Temperance Street in the district of Ardwick, themselves still witness to a variety of illicit encounters and activity. The nascent industrialisation accelerated an energy production and artificially lit landscape that was subsequently much replicated and extended around the world. Whilst the conditions for working class people reached a nadir in Manchester for the time, its role as a blueprint for the modern city proved more the dominant pattern of development than an exception as the drivers of industrial capitalism swept around the world during the remainder of the 19thC and early 20thC.27 The blackened architecture in Manchester would remain for many years, material deposits that would serve to recall the city’s dark history as its grandest buildings were coated with soot. Although furnished with some spectacular Victorian architecture, the coal fires and smoke from the nearby industry embalmed many of the city’s landmarks black prior to the Clean Air Act of 1956 which reduced pollution. Having laid claim as the first industrial city in the world, in the first half of the 20thC Manchester could arguably also have been the dirtiest as its buildings and streets were filthy and dark. Rather than being “matter out of place”28, the blanket of soot produced a city of light and darkness that was dramatic, unified and uncanny. There is an interesting point to be made here concerning the nature of this gloom. Darkness is typically associated with, and often perceived as a central feature of, night. Throughout this period, however, Manchester’s sooty textures were capable of absorbing light during the day, a phenomenon that rendered the city to be much darker than without this layer of material deposit, and further exacerbate the sense of gloom in the crepuscular hours. The landscape that resulted was highly affective, creating a very particular urban sublime that reflected the city’s industrial legacy. The implementation of the Clean Air Act of 1956 quickly removed the smog in the city and its architecture was largely returned to its original state, either by cleaning or the soot being washed off by the rain, although a couple of examples of Manchester’s ‘architecture of darkness’ still remain to the present day. By this term I am referring to a two-fold aspect of the city’s architectural landscape. Firstly, two blackened buildings from the industrial era stand as architectural testaments to Manchester’s atmospherically darkened past, namely the interior courtyards of Alfred Waterhouse’s Town Hall (1867-1877) and 22 Lever Street by Smith Woodhouse & Willoughby (1875). Secondly, the darkened built environment also provided a specific context for Manchester’s subsequent architecture to be designed for, a striking example of the latter being Casson & Condor’s District Bank Headquarters (1969) which Casson likened to a ‘lump of coal’ since the building’s cladding was “deliberately specified as dark to absorb the soot that still clung to the city’s buildings.”29

Back to topPatchwork infrastructures, blackouts and post-war reconstruction

Whereas contemporary uses for public lighting are diverse and numerous, the principal reasons for its deployment were to provide greater safety for people moving around after dark and as illumination for the flow of traffic. The association of darkness with fear and crime is longstanding, as is the notion that light prevents criminal activity. As Otter notes, Manchester was no exception to the need for safety and protection from the supposed ills of the night and the first public gas lamp in the city was established outside the police station in 1807.30 The police also operated the gasworks between 1817 and 1843 until it was passed into municipal ownership. Whilst concerns for public safety were paramount, the debate regarding both the quality and quantity of lighting in the city throughout the 19thC and early part of the 20thC were resonant with contemporary perspectives on it. For example, The Electrician stated, “to light a whole city with a huge electrical sun is a great scientific achievement; but it is not the sort of light anybody wants.”31 Given the time of writing was firmly within the heyday of electrification, this statement is all the more remarkable since it was published by the foremost electrical engineering and scientific journal of the period which typically sought to promote applications and innovations concerning electricity. More specifically, in the report Recent Developments in the Street Lighting for Manchester it is apparent that the city was perceived by its authors, Pearce and Ratcliff, as being underserved in terms of its illumination and that the contest between different forms of energy for control of the street lighting had resulted in a patchwork of provision, “to the size of the city, it will not be disputed that the amount of street lighting, totalling only 114 lamps (inclusive of 42 lamps in the Gorton district), is ridiculously small. This state of affairs has been outside the control of the Electricity Department for the simple reason that up to a very recent date the Gas Committee of the Corporation has been the street-lighting authority for the city of Manchester.”32 This situation was to end on 2nd October 1912, when the City Council placed the control of the street lighting under the authority of a Street Lighting Committee, comprised of five members of the Gas Committee, five members of the Electricity Committee and five members appointed by the Nomination Committee, the latter not being members of either of the former two committees.

Although this enabled a better provision of street lighting to develop, the efforts of the Street Lighting Committee, like many other organisations and authorities, were curtailed by the advent of the Second World War. Manchester was targeted for its importance as both an inland port and industrial city whilst neighbouring Trafford Park was a powerhouse for the production of munitions and armaments. Like so many cities and towns across Europe, Manchester operated blackout following the Lighting Restriction Order made under Defence Regulation No 24 and effective from 1st September 1939. The official notice reprinted in the Daily Telegraph stated, “[t]he effect of the order is that every night from sunset to sunrise all lights inside the buildings must be obscured and lights outside buildings must be extinguished, subject to certain exceptions in the case of external lighting where it is essential for the conduct of work of vital national importance. Such lights must be adequately shaded.”33 Air raids struck the city from August 1940, though the most significant damage took place on the nights of the 22nd and 23rd December 1940. It is estimated that almost 2,000 incendiaries were dropped on the city over these two nights following flares to enable the pilots to target their high explosives as accurately as possible. The stark transitions between darkness and sudden explosive light, silence and thundering noise can only have been terrifying. The Daily Despatch and Evening Chronicle estimated that the fire was the largest in England since the Great Fire of London in 1666 as the city centre lay “winged with red lightning and impetuous rage.”34 Compared to other cities, Manchester was not razed as comprehensively to the ground as it could have been, but the damage caused by the Second World War coupled with the need for considerable urban blight and poor living conditions had to be addressed. This led to extensive proposals for the city, not least the 1945 City of Manchester Plan by Rowland Nicholas.35 However, as with many comprehensive planning proposals during the period of post-war reconstruction, the vision was not delivered fully for a number of complex reasons. The emphasis on rebuilding war-damaged and run-down areas of the city resulted in some fine examples of modernist-inspired architecture during the 1960s although the most significant building in the city centre, Wilson & Womersley’s Arndale Centre constructed between 1972 and 1980, as Hartwell has observed was only memorable for its sheer size and inward-looking design.36 Development across the 1970s, 1980s and early 1990s was largely piecemeal and arguably without a coherent and clear direction, a situation considerably worsened by a major economic recession. Indeed, as Parkinson-Bailey notes, “although a number of sites in the city had been earmarked in the 1980s for potential development, most of them remained as derelict brownfield sites or car parks, and the nearest these schemes came to realisation was the artist’s vision painted on the hoardings which surrounded the site.”37

Back to topRecent development and the desire for increased urban lighting

The most recent phase of major redevelopment in Manchester followed the 1996 IRA bomb. The largest bomb detonated in the UK since the Second World War, it caused huge damage to the city centre precipitating the mass regeneration that has continued to the present day. In 2002, Manchester hosted XVII Commonwealth Games which was widely regarded a success. These two events emboldened the city to either demolish or re-develop large sections of the city centre, producing an entertainment and retail landscape that whilst contemporary perhaps is less unique than before. Most notable in these parts of the city centre is the high degree of illumination coherent with many city centres to provide a legible and safe landscape which needs to be reconsidered.38

In Planning the Night-time City, Roberts and Eldridge examine some of the challenges for planners and town/city centre managers as we move toward the 24-hour city in the early twenty-first century.39 An explicit and recurring theme in their synthesis is that the night-time is framed, developed and performed in a different manner to the quotidian activities of the day. Historical accounts have shown how the night has long been associated with pleasure, transgression and freedom. This can take many forms but may often be a type of pleasure seeking. The expectation of pleasure is a counterpoint and acts directly in opposition to day-time activities which are generally understood as relating to everyday worlds of labour, business and finance. But we also know that everyday activities such as convenience shopping or attending the gym have gradually expanded into the early morning or late into the evening. Notions of work and workplace have changed and eating out more commonplace, shifts which typically conceal the respective conditions of labour and economic status of those supporting such activities and services. For the night and timeframe of darkness is also an assemblage of uneven economic, political and social geographies since it belies a working population that reflects, to varying degrees, their ethnicity, immigration status, race and limited and/or precarious labour opportunities, as determined by their context.

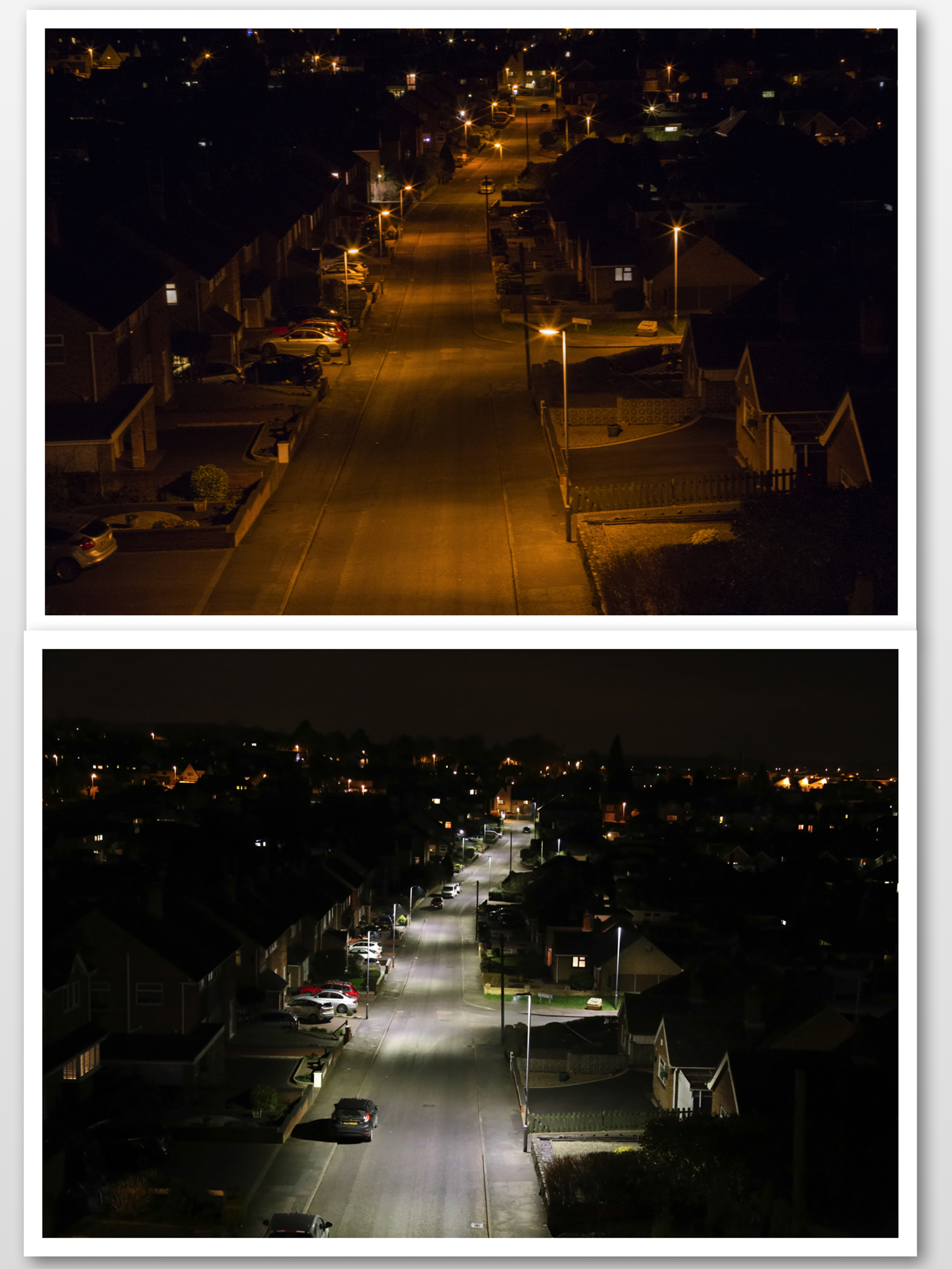

As cities such as Manchester utilise techniques of illumination to extend their commercial offer in terms of both space and time, it raises questions about the experiences available in our urban landscapes and whether it is possible to find different lights and darknesses beyond the formally sanctioned, and typically commercially driven, festivals that occur. Further, as Manchester rolls out its comprehensive replacement of 56,000 lamps with new LED lights, it is clear that the process with its significant environmental and economic benefits will also change the character of many parts of the city for the foreseeable future as illustrated in figure 1.

Having been used in a number of major streetlight replacement projects around the globe, including Copenhagen, Los Angeles, New York and Shanghai, LED street lighting is evidently a popular choice for cities wanting to reduce their lighting energy costs though their impact has positive and negative effects as Bramley has reported.40 This ongoing entanglement between different lights and darknesses and the sources that produce them in urban environments continues. Despite the supposed benefits to efficiency in lighting technologies, Kyba, Hänel, and Hölker note that energy usage for outdoor lighting and artificial night-time brightness continues to increase annually.41 A recent article by Petrusich stated that “new LED streetlights are almost universally described as unpleasant”42, yet there are emerging responses to this view as Blander argues in the quest for letting ‘night be night’ where lighting designers are now seeking to develop a “holistic view of outdoor illumination, examining diverse sources and gradations of light, and advocating more thoughtfully conceived lighting systems that work with, rather than in opposition to, night-time darkness.”43 This rethinking is timely and significant, running counter as it does to the way in which urban lighting has been developed to date. Indeed, as Bille and Sørensen observe, “we generally continue to pursue quantity at the expense of quality of illumination when technological development is offering so many new opportunities.”44 These values of light, clarity, cleanliness and coherence are Western in their origin yet have been transferred across the global experience of culture more broadly.

In Britain, the current opportunities for a plurality and significant diversity of urban lighting are at present highly constrained by regulations imposed on street lighting which must conform to British Standard 5489 1:2013 Code of practice for the design of road lighting: Lighting of roads and public amenity areas.45 Regulatory frameworks and codes of practice such as this are common in many countries and suggest how little we understand of different lights and darknesses. It is therefore my intention to record the urban landscape of Manchester with its different lights and darknesses before they are lost. This loss is not absolute but direct experience of the current variety of darknesses is likely to be obstructed, or at least hindered, by the profusion of LED street lighting. It is important to emphasise here that the comprehensive installation of ‘new’ lighting across the city, as with many strategies to establish total and uniform environments, is unlikely to produce a coherent landscape at night. This is because the planned power of completeness is illusory since the lighting technology is built over, and responds to, a longer history of partial infrastructures and contextual characteristics that shape its effects.46 As such, difference will still persist or reassert itself across the city, albeit in ways potentially unforeseen and unintended. In order to capture some of the different atmospheres and ambiances of darknesses in Manchester at present, I use the following section of the article to present a combination of my autoethnographic fieldwork (in italics) interspersed with images to assist the reader’s understanding of how the quality and quantity of lighting in these places mediate experiences of the built environment.

Back to topWalking in the city after dark

Strangeways here we come. But first: the cathedral. Gothic Perpendicular upgraded from parish church and hewn from the stone of nearby Collyhurst. Here, the subtle interplay between the sodium street light, the directional wash of coloured light up the cathedral’s tower and the white light of its clock augment its brooding presence. Beneath my feet, the nearby Victorian Arches – the prize in the urban explorer's eyes – tricky to access these days, encumbered by the river, the infrastructure and the resolute locking down of (no) entry points. Feel that? The gravitational field has been breached once again as the centripetal force of the inner ring road is crossed. Back against the Manchester Arena, the city's mouth gapes open at this point. Drawn out along Great Ducie Street and behold: the epic asterisk plan of brick. Her Majesty’s Prison Manchester will always be Strangeways to me, in the same way that for some Manchester Airport will always be Ringway, the rebranding and replaced signage never able to fully scrub the mind's palimpsest as ghost letters cling to their former sanctuary, the typescript stencilled in dirt. The streets either side of the prison are phantom escalators, feet unable to resist the upward heave of the compound's heft. A lone figure now set against a huge brick wall, multiple eyes of the surveillance cameras blankly looking back at me but unable to return any expression. My shadow grows and shrinks against the brick canvas in rhyme with the streetlights. The atmosphere here within the admixture of sodium glow foregrounded by the piercing beams of security lights, the urban environment is quiet, contemplative, almost subterranean.

I am now compressed in the wonderful push-pull of Library Walk. Perhaps the most dynamic open space in the city but not for much longer. Its nights are numbered, soon to become an impasse as the place is shielded from public feet and fettered with shiny, bulbous science-fiction adornments. This thing called progress lacerates the enchanting and favours the money. Derelict ideology requires the demolition of the cherished and savoured, all built on the shifting sands of finance. Booth Street cautions the legs past the police headquarters – nothing to see here officers. Then a dogleg across Deansgate and down towards the discordance of the Museum of Science and Industry and the excavated sets for the television show Coronation Street. Castlefield bowls out too soon to stack after stack of apartment blocks and incongruous fluorescence. Industrial heritage and its ruins crisscross around here, infrastructural behemoths of former success now speechless, corroding and beautiful as they run above sodium lamps. The origins of the city lie here, Mancunium, civic stones, the very bones of former settlements desecrated for the progress of the canal and railway, now reconstructed as heritage motifs for public acknowledgement. Eerie and vulnerable, the massiveness of the area and its artefacts is pliable and yields to the feet easily as archways and pillar frame new views and oddments of the past.

Moving across the city now, the background slish of traffic on the Mancunian Way overhead as I emerge from the subway, ears prickled by the smashing of glass somewhere behind. This is Manchester, on a cool and dry night in late May where the opacity of the city’s infrastructure loses its gravity and melds toward the neon and sodium morse code above. Indecipherable messages, these ghost texts to unknown gods and spirits hang in the air like stolen thoughts from another time – the lost future that got delayed, tied down in the bondage of bureaucracy, boredom and blame. But now the shouting is all over. Instead, this award-winning concrete serpent remains frozen against asphalt forever, undulating between buildings and woven across the landscape. My left foot skids on the masticated remains of a club flyer chewed by rain and indifference. And yet this crepuscular beast, somehow always in the twilight due to the amount of sodium lighting around to, comes alive as the beams of motor cars traverse above and underneath it; a dizzying and dynamic shadow-play stirring the creature’s geometry into motion as vehicles suddenly appear and recede with their white headlights and trails of red rear lights.

The pylon filigree makes poor company for its silver-birch brethren in the dim, clouded moonlight as the molten ebony of the Mersey River smears past below. Tonight, I am walking along the city’s edge as I navigate an arc, less precise than the orbital motorway in the distance. Pushing up the riverbank, past the flood line of winter swelling, and across the bridge toward the scanty woods. A tent in the trees seems to be losing its tautness against the weather. Somewhere in the undergrowth, a small fox stirs and then skits across the path away from the crunch of boots and human scent. The cold, wintry air brings with it an ocular sharpening as the edges of flora and the longer grasses suddenly lean into view, the murky assemblage instantly composed like decoupage. Onward towards Wythenshawe, that bastion of Garden City displacement where the pitch shifter of the landscape alters from deadened calm and occasional rustling to an altogether more eerie quiet. Emerging from the jaundiced concrete flyover that arcs a man-made swathe and announces the end of nature, the orange glow of street lighting increases in as it punctuates the way forward, suburban homes lining the perspective on either side. A car sheens its way around the corner, lights off then headlights all ablaze as its exit velocity from the estate increases exponentially into the murk beyond. Satellite lives flicker lonely blues and greens behind glass portals and the distant smeared sounds of cars over the rooftops brum and fade away. Several turns later and the edge of Wythenshawe Park cascades away either side of me. The sentry of trees are filtered through and the vast carpet of the park rolls out, a luxurious deep-pile affair, feet sinking into the soft surface, bedecked with curvaceous mirrors where the land lies low and is saturated. The puddles stare back, reflecting the clouds overhead and a damp and dishevelled silhouette. The ground offers poor resistance to leather and rubber rhythms of my footwear, instead pulling each footstep further into the quagmire and pooling rainwater with each depression. Underneath the motorway, down a charcoal grey lane, a sodium lamp signals the residence for someone. Retracing my steps, the walk home leads to the ultimate denouement as I discover the immediate effects of the city’s street light replacement programme on my own street, now a jumbled composition of directional, white LED lamps and the gradual oranges of sodium lighting.

Understanding the diversity and coexistences of darkness

What I intend to become evident through these textual and visual depictions is the rich potential of the night for our senses as a place for speculation and experience.47 Walking through Manchester at night, the city slowly but perceptibly shifts in its composition of different lights and darknesses, reflecting the history of its lighting energy landscape. Perhaps unsurprisingly, historical accounts of lighting have focused on the routine circumstances of the urban night.48 Though more recent studies have redressed this by providing investigations into unique, temporary and performative illuminations49, there may be an important overlap between these two areas of inquiry. That we can go and enjoy our nocturnal urban landscape improvisionally without recourse to consumerism suggests that by engaging with the ‘every night’ we might find ourselves open to new forms of experience and place.50 Although there is an increasing amount of research across various disciplines related to the notion of the reciprocity and nuances between light and darkness being essential to each, there are also historical clues to how we might learn to embrace this. The Japanese novelist Jun'ichirō Tanizaki in his seminal 1933 meditation on his country’s culture, In Praise of Shadows, highlighted the importance of this coexistence when he observed, “[i]f light is scarce then light is scarce; we will immerse ourselves in the darkness and there discover its own particular beauty.”51

Writing about gloom and the urban landscape, Tim Edensor provides a robust argument for embracing it, “[r]ather than being lamented, the re-emergence of urban darkness, although not akin to the medieval and early-modern gloom that pervaded city space, might be conceived as an enriching and a re-enchantment of the temporal and spatial experience of the city at night.”52 This relational understanding between lights and darknesses is crucial to how we might conceive of better ways to illuminate and engage with our cities at night. As our cities, not least Manchester, seek to evolve into 24-hour places reducing further the different types of atmospheres, lights and darknesses seems contrary to the increased diversity of their populations, cultures, social meanings and values. Understanding that darkness is “situated, partial and relational”53 is essential to recognising what may be lost in our cities since it contributes significantly to “affective atmospheres”54 of the urban. At a period in human history when so much of our activity is uploaded, categorised, tagged and compressed into moments, I contend that to sense a wider and deeper world directly through first hand encounter becomes more important than ever. Moving, quite literally, out of the glare and stare of our commoditized and structured days and into alternative modalities within the shadows of our cities may be one of the few truly sublime and beautiful practices available to us.

This is not simply a matter of replacing existing urban lighting with more energy efficient forms of it, but rather a vital and important need to examine its health implications since the distribution and intensity of urban lighting results in a detrimental and serious disruption to the circadian clocks of numerous species including human beings.55 Furthermore, important in this context is the need to better understand the value of different lights and darknesses56; their qualities and effects so that we may further appreciate the array and nuances of lighting available to us as a means of situating us in our place, whether Manchester or elsewhere.57 The methods presented here are part of a foray into examining and experimenting with the reciprocity between our senses and the built environment when the latter is experienced outside of the daytime hours. It is a nascent body of multi- and inter-disciplinary work. Yet it is also important to remember that our senses are culturally conditioned, alongside our view of darkness, being as they are bound up in specific historical, geographical and social circumstances and interrelationships. To conclude, I suggest that by building different knowledges and understandings of the complex relationships between light and darkness, their distinct qualities and their coexistences, we can also reveal the diverse meanings and experiences that not only contribute to the history of energy as manifest in illuminating our urban landscapes but also its future.

- 1. Ben Gallan, Chris Gibson, “New dawn or new dusk? Beyond the binary of day and night”, Environment and Planning A, vol. 43, n° 11, 2011. Robert Shaw, “Night as Fragmenting Frontier: Understanding the Night that Remains in an era of 24/7”, Geography Compass, vol. 9, n° 12, 2015. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12250

- 2. Nick Dunn, Dark Matters: A Manifesto for the Nocturnal City (Winchester: Zero, 2016).

- 3. Matthew Gandy, “Negative Luminescence”, Annals of the American Association of Geographers, vol. 107, n° 5, 2017. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/246944 52.2017.1308767

- 4. Roger A. Ekirch, At Day’s Close: A History of Nighttime (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2005).

- 5. Bryan D. Palmer, Cultures of Darkness: Night Travels in the Histories of Transgression (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2000).

- 6. Oliver Dunnett, “Contested landscapes: the moral geographies of light pollution in Britain”, Cultural Geographies, vol. 22, n° 4, 2015, 622.

- 7. Marion Dowd, Robert Hensey (eds.), The Archaeology of Darkness (Oxford: Oxbow, 2016). Nancy Gonlin, April Nowell (eds.), Archaeology of the Night: Life After Dark in the Ancient World (Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, 2018). Roy Sorensen, Seeing Dark Things: The Philosophy of Shadows (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

- 8. Wolfgang Schivelbusch, Disenchanted Night: The Industrialization of Light in the Nineteenth Century (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1988).

- 9. Joachim Schlör, Nights in the Big City Trans. Pierre Gottfried Imhof and Dafydd Rees Roberts (London: Reaktion Books, 1998), 57.

- 10. Peter Davidson, The Last of the Light: About Twilight (London: Reaktion, 2015).

- 11. William Chapman Sharpe, New York Nocturne: The City After Dark in Literature, Painting, and Photography, 1850-1950 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008).

- 12. Robert Williams, “Nightspaces: Darkness, Deterritorialisation, and Social Control”, Space and Culture, vol. 11, n° 4, 2008, 514. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/120633 1208320 117

- 13. Reclaim the Night, http://www.reclaimthenight.co.uk

- 14. Take Back the Night, https://takebackthenight.org

- 15. Dave Haslam, Life After Dark: A History of British Nightclubs and Music Venues (London: Simon & Schuster, 2015).

- 16. Cătălin D. Gălăţanu, “Study of Facades with Diffuse Asymmetrical Reflectance to Reduce Light Pollution”, Energy Procedia, vol. 112, March 2017. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2017.03.1100

- 17. Pierantonio Cinzano, Fabio Falchi, “The propagation of light pollution in the atmosphere”, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, vol. 427, n° 4, 2012. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21884.x

- 18. Manchester City Council, Street Lighting LED Retrofit Programme, Executive Report, 12th February 2014. Available at: http://www.manchester.gov.uk/meetings/meeting/2042/ executive/attachment/16500

- 19. Joseph Wheeler, Manchester. Its Political, Social and Commercial History, Ancient and Modern (Manchester: Simms and Dinham, 1836), 256.

- 20. Mike Williams, “The Mills of Ancoats”, Manchester Region History Review, n° 7, 1993.

- 21. Jonathan Crary, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep (London: Verso, 2013), 61-62.

- 22. Thomas Carlyle, Past and Present (London: n.d, 1843), 247.

- 23. Charles Dickens, Hard Times (London: Chapman & Hall, Ltd., 1905 [Reprint]).

- 24. Alexis de Tocqueville, Journeys to England and Ireland Ed. Jacob Peter Mayer. Trans. George Lawrence and K. P. Mayer (London: Faber and Faber, 1958 [Reprint]), 108.

- 25. Wolfgang Schivelbusch, Disenchanted Night: The Industrialization of Light in the Nineteenth Century (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1988).

- 26. Friedrich Engels, The Condition of the Working-Class in England Trans. Florence Kelley Wischnewetsky (London, 1892), 53.

- 27. Harold L. Platt, Shock Cities: The Environmental Transformation and Reform of Manchester and Chicago (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2005).

- 28. Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger: An Analysis of the Concepts of Pollution and Taboo (London: Ark Paperbacks, 1966).

- 29. Richard Brook, Manchester Modern (Manchester: The Modernist Society, 2017).

- 30. Chris Otter, “Let There Be Light: Illuminating Modern Britain”, History Today, vol. 58, n° 10, 2008, 20.

- 31. The Electrician, 7th May 1881 (London: James Gray), 325.

- 32. S. L. Pearce, H. A. Ratcliff, “Recent Developments in the Street Lighting of Manchester”, Journal of the Institution of Electrical Engineers, vol. 50, n° 219, 1913, 598.

- 33. “Black-out regulations came into force at sunset last night”, Daily Telegraph, 2 September 1939.

- 34. “Our Blitz: Red Sky over Manchester”, Daily Dispatch and Evening Chronicle (Manchester: Kemsley Newspapers), 5 January 1941, 19.

- 35. Rowland Nicholas, City of Manchester Plan (Norwich: Jarrold & Sons Ltd., 1945).

- 36. Clare Hartwell, Manchester (London: Penguin, 2001).

- 37. John J. Parkinson-Bailey, Manchester: An Architectural History (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000), 233.

- 38. ARUP, Cities Alive: Rethinking the Shades of Night (London: Arup, 2015).

- 39. Marion Roberts, Adam Eldridge, Planning the Night-time City (Oxon: Routledge, 2009). Wolfgang Schivelbusch, Disenchanted Night: The Industrialization of Light in the Nineteenth Century (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1988).

- 40. Ellie Violet Bramley, “Urban light pollution: why we’re all living with permanent ‘mini jetlag’”, The Guardian, 23 October 2014. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/ 2014/oct/23/-sp-urban-light-pollution-permanent-mini-jetlag-health-unnatural-bed

- 41. Christopher Kyba, Andreas Hänel, Franz Hölker, “Redefining efficiency for outdoor lighting”, Energy & Environmental Science, n° 7, 2014.

- 42. Amanda Petrusich, “Fear of the light: why we need darkness”, The Guardian, 23 August 2016. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/aug/23/why-we-need-darknes…

- 43. Akiva Blander, “Can Designers Combat Light Pollution by Embracing Darkness?”, Metropolis, 2 May 2018. Available at: http://www.metropolismag.com/cities/lighting-designers-fighting-back-be…

- 44. Mikkel Bille, Tim Flohr Sørensen, “An Anthropology of Luminosity: The Agency of Light”, Journal of Material Culture, vol. 12, n° 3, 2007, 271.

- 45. British Standards Institute, BS5489 1:2013 Code of practice for the design of road lighting: Lighting of roads and public amenity areas, 2013. Available at: https://www.standardsuk.com /products/BS-5489-1-2013

- 46. David E. Nye, When the Lights Went Out: A History of Blackouts in America (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2010).

- 47. Photophilos, Hints for Increasing the splendour of illumination; securing the pleasure of the spectator, and the convenience of the householder, with some remarks for the prevention of tumult and disorder. Particularly adapted to the illuminations expected to take place on the proclamation for peace with the French republic (London, 1801).

- 48. Chris Otter, The Victorian Eye: A Political History of Light and Vision in Britain, 1800-1910 (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2008). Joachim Schlör, Nights in the Big City Trans. Pierre Gottfried Imhof and Dafydd Rees Roberts (London: Reaktion Books, 1998).

- 49. Alice Barnaby, Light Touches: Cultural Practices of Illumination, London 1800-1900 (Abingdon: Routledge, 2015). Tim Edensor, “Illuminated atmospheres: anticipating and reproducing the flow of affective experience in Blackpool”, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, vol. 30, n° 6, 2012. Tim Edensor, Mikkel Bille, “’Always like never before’: learning from the lumitopia of Tivoli Gardens”, Social & Cultural Geography, 2017. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1464936 5.2017.1404120

- 50. Nick Dunn, Dark Matters: A Manifesto for the Nocturnal City (Winchester: Zero, 2016). Tim Edensor, From Light to Dark: Daylight, Illumination, and Gloom (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2017).

- 51. Jun'ichirō Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows Trans. Thomas J. Harper and Edwards G. Seidensticker (London: Vintage, 2001[1933]), 48.

- 52. Tim Edensor, “The Gloomy City: Rethinking the Relationship between Light and Dark”, Urban Studies, vol. 52, n° 3, 2015, 436.

- 53. Nina Morris, “Night walking: Darkness and sensory perception in a night-time landscape installation”, Cultural Geographies, vol. 18, n° 3, 2011, 316.

- 54. Ben Anderson, “Affective atmospheres”, Emotion, Space and Society, vol. 2, n° 2, 2009. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2009.08.005

- 55. Steve M. Pawson, Martin K.-F. Bader, “LED lighting increases the ecological impact of light pollution irrespective of color temperature”, Ecological Applications, vol. 24, n° 7, 2014. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1890/14-0468.1

- 56. Taylor Stone, “The Value of Darkness: A Moral Framework for Urban Nighttime Lighting”, Science and Engineering Ethics, vol. 24, n°2, 2018. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-9924-0

- 57. Robert Shaw, “Streetlighting in England and Wales: New technologies and uncertainty in the assemblage of streetlighting infrastructure”, Environment and Planning A, vol. 46, n° 9, 2014.

Anderson Ben, “Affective atmospheres”, Emotion, Space and Society, vol. 2, n° 2, 2009, 77-81. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2009.08.005

ARUP, Cities Alive: Rethinking the Shades of Night (London: ARUP, 2015).

Barnaby Alice, Light Touches: Cultural Practices of Illumination, London 1800-1900 (Abingdon: Routledge, 2015).

Bille Mikkel, Sørensen Tim Flohr, “An Anthropology of Luminosity: The Agency of Light”, Journal of Material Culture, vol. 12, n° 3, 2007, 263-284.

“Black-out regulations came into force at sunset last night”, Daily Telegraph, 2 September 1939.

Blander Akiva, “Can Designers Combat Light Pollution by Embracing Darkness?”, Metropolis, 2 May 2018. Available at: http://www.metropolismag.com/cities/lighting-designers-fighting-back-behalf-darkness-night/

Bramley Ellie Violet, “Urban light pollution: why we’re all living with permanent ‘mini jetlag’”, The Guardian, 23 October 2014. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2014/oct/23/-sp-urban-light-pollution-permanent-mini-jetlag-health-unnatural-bed

British Standards Institute, BS5489 1:2013 Code of practice for the design of road lighting: Lighting of roads and public amenity areas, 2013.Available at: https://www.standardsuk.com/products/BS-5489-1-2013

Brook Richard, Manchester Modern (Manchester: The Modernist Society, 2017).

Carlyle Thomas, Past and Present (London: n.d, 1843).

Cinzano Pierantonio, Falchi Fabio, “The propagation of light pollution in the atmosphere”, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, vol. 427, n°4, 2012, 3337-3357. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21884.x

Crary Jonathan, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep (London: Verso, 2013).

Davidson Peter, The Last of the Light: About Twilight (London: Reaktion, 2015).

Dickens Charles, Hard Times (London: Chapman & Hall, Ltd., 1905 [Reprint]).

Douglas Mary, Purity and Danger: An Analysis of the Concepts of Pollution and Taboo (London: Ark Paperbacks, 1966).

Dowd Marion, Hensey Robert (eds.), The Archaeology of Darkness (Oxford: Oxbow, 2016).

Dunn Nick, Dark Matters: A Manifesto for the Nocturnal City (Winchester: Zero, 2016).

Dunnett Oliver, “Contested landscapes: the moral geographies of light pollution in Britain”, Cultural Geographies, vol. 22, n° 4, 2015, 619-636.

Edensor Tim, “Illuminated atmospheres: anticipating and reproducing the flow of affective experience in Blackpool”, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, vol. 30, n° 6, 2012, 1103-1122.

Edensor Tim, “The Gloomy City: Rethinking the Relationship between Light and Dark”, Urban Studies, vol. 52, n° 3, 2015, 422-438.

Edensor Tim, From Light to Dark: Daylight, Illumination, and Gloom (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2017).

Edensor Tim, Bille Mikkel, “’Always like never before’: learning from the lumitopia of Tivoli Gardens”, Social & Cultural Geography, 2017. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1464936 5.2017.1404120

Ekirch Roger A., At Day’s Close: A History of Nighttime (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2005).

Electrician The, 7th May 1881 (London: James Gray).

Engels Friedrich, The Condition of the Working-Class in England Trans. Florence Kelley Wischnewetsky (London, 1892).

Gălăţanu Cătălin D., “Study of Facades with Diffuse Asymmetrical Reflectance to Reduce Light Pollution”, Energy Procedia, vol. 112, March 2017, 296-305. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2017.03.1100

Gallan Ben, Gibson Chris, “New dawn or new dusk? Beyond the binary of day and night”, Environment and Planning A, vol. 43, n° 11, 2011,2509-2515.

Gandy Matthew, “Negative Luminescence”, Annals of the American Association of Geographers, vol. 107, n° 5, 2017, 1090-1107. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2017.1308767

Gonlin Nancy, Nowell April (eds.), Archaeology of the Night: Life After Dark in the Ancient World (Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, 2018).

Hartwell Clare, Manchester (London: Penguin, 2001).

Haslam Dave, Life After Dark: A History of British Nightclubs and Music Venues (London: Simon & Schuster, 2015).

Kyba Christopher, Hänel Andreas, Hölker Franz, “Redefining efficiency for outdoor lighting”, Energy & Environmental Science, n°7, 2014, 1806-1809.

Manchester City Council, Street Lighting LED Retrofit Programme, Executive Report, 12thFebruary 2014. Available at: http://www.manchester.gov.uk/meetings/meeting/2042/executive/attachment/16500

Morris Nina, “Night walking: Darkness and sensory perception in a night-time landscape installation”, Cultural Geographies, vol. 18, n° 3, 2011, 315-342.

Nicholas Rowland, City of Manchester Plan (Norwich: Printed and pub. for the Manchester Corporation by Jarrold & Sons Ltd., 1945).

Nye David E., When the Lights Went Out: A History of Blackouts in America (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2010).

Otter Chris, “Let There Be Light: Illuminating Modern Britain”, History Today, vol. 58, n° 10, 2008, 16-22.

Otter Chris,The Victorian Eye: A Political History of Light and Vision in Britain, 1800-1910 (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2008).

“Our Blitz: Red Sky over Manchester”, Daily Dispatch and Evening Chronicle (Manchester: Kemsley Newspapers), 5 January 1941.

Palmer Bryan D., Cultures of Darkness: Night Travels in the Histories of Transgression (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2000).

Parkinson-Bailey John J., Manchester: An Architectural History (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000).

Pawson Steve M., Bader Martin K.-F., “LED lighting increases the ecological impact of light pollution irrespective of color temperature”, Ecological Applications, vol. 24, n° 7, 2014, 1561-1568. Available at:https://doi.org/10.1890/14-0468.1

Pearce S. L., Ratcliff H. A., “Recent Developments in the Street Lighting of Manchester”, Journal of the Institution of Electrical Engineers, vol. 50, n° 219, 1913, 596-634.

Petrusich Amanda, “Fear of the light: why we need darkness”, The Guardian, 23 August 2016. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/aug/23/why-we-need-darknes…

Photophilos, Hints for Increasing the splendour of illumination; securing the pleasure of the spectator, and the convenience of the householder, with some remarks for the prevention of tumult and disorder. Particularly adapted to the illuminations expected to take place on the proclamation for peace with the French republic (London, 1801).

Platt Harold L., Shock Cities: The Environmental Transformation and Reform of Manchester and Chicago (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2005).

Reclaim the Night, http://www.reclaimthenight.co.uk

Roberts Marion, Eldridge Adam, Planning the Night-time City (Oxon: Routledge, 2009).

Schivelbusch Wolfgang, Disenchanted Night: The Industrialization of Light in the Nineteenth Century (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1988).

Schlör Joachim, Nights in the Big City Trans. Pierre Gottfried Imhof and Dafydd Rees Roberts (London: Reaktion Books, 1998).

Sharpe William Chapman, New York Nocturne: The City After Dark in Literature, Painting, and Photography, 1850-1950 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008).

Shaw Robert, “Streetlighting in England and Wales: New technologies and uncertainty in the assemblage of streetlighting infrastructure”, Environment and Planning A, vol.46, n° 9, 2014, 2228–2242.

Shaw Robert, “Night as Fragmenting Frontier: Understanding the Night that Remains in an era of 24/7”, Geography Compass, vol. 9, n° 12, 2015, 637-647. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12250

Sorensen Roy, Seeing Dark Things: The Philosophy of Shadows (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

Stone Taylor, “The Value of Darkness: A Moral Framework for Urban Nighttime Lighting”, Science and Engineering Ethics, vol. 24, n°2, 2018, 607-628. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-9924-0

Take Back the Night, https://takebackthenight.org

Tanizaki Jun'ichirō , In Praise of ShadowsTrans. Thomas J. Harper and Edwards G. Seidensticker (London: Vintage, 2001[1933]).

Tocqueville Alexis de, Journeys to England and Ireland Ed. Jacob Peter Mayer. Trans. George Lawrence and K. P. Mayer (London: Faber and Faber, 1958 [Reprint]).

Wheeler Joseph, Manchester. Its Political, Social and Commercial History, Ancient and Modern (Manchester: Simms and Dinham, 1836).

Williams Mike, “The Mills of Ancoats”, Manchester Region History Review, n°7, 1993, 27-32.

Williams Robert, “Nightspaces: Darkness, Deterritorialisation, and Social Control”, Space and Culture, vol. 11, n° 4, 2008, 514-532. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/120633 1208320 117