Oil pricing and the challenge of an Arab oil trans-nationalism: Abdallah al-Tariqi and Arab oil globalization

Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne University

philippe.petriat[at]univ-paris1. fr

The author wishes to thank the reviewers for their most valuable comments on the previous version of this article, as well as the careful editing of the journal’s editors. Natasha Pesaran, in particular, kindly and very tactfully edited the English version.

Economics was a major field of struggle for anti-imperialist oil experts and activists. Building on recent scholarship on oil anti-colonialism, this article argues that exploring the economic dimension of the struggle for sovereignty not only adds to our understanding of political and social movements, but also illuminates the ways in which anti-imperialist oil experts and activists have envisioned economic globalization and its challenges, as well as material struggles over oil in developing countries during the 1960s and early 1970s. “Petro-knowledge” was not limited to elite gatherings and political debates. This article provides insight into the circulation of “petro-knowledge” and its diverging echoes beyond elite networks by exploring hitherto neglected aspects of ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi’s transnational career prior to the 1973 oil shock. It sheds light on the way in which this expertise was used during the 1960s. By emphasizing the economic aspects of this knowledge and exploring the ways it has been popularized and championed, the article aims to reevaluate the development of anti-colonial oil strategies and their impact, without solely focusing on their political contents and on the 1973 oil crisis as a pivotal moment.

Introduction

In February 21, 1971, at the Kuwaiti Nadi al-Istiqlal (the Independence Society), the oil expert ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi (1918-1997) delivered a public and well-attended lecture on “Oil prices”, the content of which was published in the March issue of the leftist magazine al-Tali‘a (The Avant-garde).1 In his introduction, Tariqi stressed “there is no issue more important in Kuwait than oil, and there is no political issue more important than oil politics.” However, before addressing this important topic, he reminded his audience that it was necessary for every citizen to strive to “grasp the problems and complexities of the oil industry.” To this end, ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi, as a good pedagogue, emphasized his goal of “simplifying” the issue of oil prices for his listeners.

Since the implementation of the 50-50 formula in 1948 in Venezuela, and its subsequent adoption in Saudi Arabia in 1950 and other Gulf countries in the years that followed, the terms of compensation for oil-producing countries had remained largely unchanged. Oil in the Middle East was primarily extracted in accordance with a system of agreements known as concessions. These agreements had been concluded in the late 1920s and early 1930s in Gulf countries. They gave full control to concessionary oil companies (Aramco in Saudi Arabia and the Kuwait Oil Company in Kuwait) over levels of production and the fixing of “posted” (official) prices that served as basis for the calculation of the revenues to be paid to local governments in addition to royalties: tax on net profits declared by the companies (50% in adherence with the terms of the 50-50 agreements). Governments had limited involvement in the process as officials were not included in decision making and oil companies typically sold their output to their own parent companies (Anglo-Iranian Oil Company and Gulf Oil for Kuwait Oil Company, Standard Oil of California, Texas Oil, Standard Oil of New Jersey and Socony Vacuum for Aramco), usually at prices discounted from posted prices.

As he often did in his writings and lectures, ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi began his presentation with a historical overview that focused on the Arab and developing countries, before addressing the recent Tehran agreement that had been concluded the previous week on February 14. Tariqi highlighted the prolonged struggle of Arab oil-producing nations to raise oil prices. In 1970, Libya had set a precedent by unilaterally imposing its own terms for crude pricing and taxation on the profits of mainly foreign-owned companies operating in the country. According to Tariqi, who served as a consultant during the development of the Libyan decision, the Libyan decisions had set the stage for subsequent negotiations. In December 1970 at a meeting in Caracas, OPEC countries agreed to adopt the highest prices set by any member country, and to begin negotiations with oil companies under the direction of the Iranian minister of oil, Jamshid Amouzegar. In February 1971 at Tehran, Gulf OPEC members and representatives of the foreign oil companies operating in the Middle East reached an agreement on an unprecedented increase in both the posted prices of oil and tax rates. The negotiations culminated in April 1971, in Tripoli, where Libya, Algeria, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq secured even higher posted prices for the share of their oil production exported by pipelines to the Mediterranean.

‘Abdallah al-Tariqi hesitated when assessing the benefits and the shortcomings of the Tehran agreement. Speaking at the progressive and anti-imperialist Nadi al-Istiqlal, he took a critical approach toward the agreement, on the basis of its political effects, adopting a stance which echoed that of other Middle Eastern oil experts. Yet in other writings, Tariqi proved more positive in his assessment of the Tehran agreement as he emphasized the economic benefits that had been achieved. In this article, I argue that Tariqi’s ambiguous position and the challenges he faced in explaining economic concepts to his audience are indicative of the nuanced and fragile role of economics in the history of anti-imperialism in developing nations.

This becomes clear from his attempts to address the intricate, unappealing, and economic issue of oil prices. ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi strove to tackle this issue and make it “easier” or more comprehensible to his Kuwaiti audience of February 21, 1971, as he did in articles and lectures that he continued to deliver into the late 1970s. As he argued at the Nadi al-Istiqlal, “oil prices are not of the utmost importance when dealing with the oil industry because there are other, more important, benefits.” Indeed, prices were just one aspect of what ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi considered the overall shortcomings of the Arab oil industry. However, oil prices and the determination of prices were a primary focus due to the recent Tehran agreement and the upcoming negotiations between oil companies, Libya, and Algeria for Mediterranean crude. Tariqi also characterized prices as a clear indication of the problematic structure of the oil industry.

The pursuit of economic development funded by oil revenues was a priority for Arab States, making the issue of oil prices a driving force for achieving true independence and promoting regional solidarity. For many years, oil had been the cornerstone of transnational industrial development plans championed by ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi and a number of his colleagues. In an era of decolonization, it served as a catalyst for development and a powerful tool in the struggle for effective independence, particularly as a symbol of the corporate imperial power exercised by Western oil companies in managing the natural resources of newly decolonized countries until the early 1970s. The economics of oil played a central role in shaping the national and transnational priorities of raw material producers. However, these priorities gradually diverged after 1971 as oil operations became primarily international and control of the market shifted from consumers to producing countries. The increasing role of state officials and related traders in setting prices, as well as the disconnect between the national and transnational levels of oil-driven development schemes in producer countries, led to competition among producers and among the Third World as a whole.2 Middle Eastern producers argued for continuous increases in oil prices, putting the revenues derived from oil at the forefront of national development plans, to the disadvantage of developing countries without significant oil resources. Tariqi’s examination of the Tehran agreements highlights the advantages and disadvantages of the pinnacle of nation-state power in the Third World, demonstrated through negotiations with oil companies. At the same time, multinational corporations like oil companies were just starting to rise in the global economy.3 Recent critical literature has begun to examine the importance of oil prices and their calculation in the transformation of the global market and the growing role played by oil within it. However, the literature fails to acknowledge the insightful observations of Middle Eastern experts like Tariqi.4 The power of oil-producing states in decision-making and the shift to a producer oil market reached its height during the period of oil nationalizations, which began with Algerian nationalization of oil in 1971 and ended with Saudi Arabia’s oil nationalization in 1980. At the same time, rising prices and oil revenues or “petrodollars” supported the market’s gradual financialization. In short, the issue of oil prices as understood by ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi and his audience sheds light on the evolving nature of Arab oil globalization and their understanding of its shifting trajectory prior to the events of 1973. Tracing back these changes and viewing them through the lens of Arab oil experts and activists outside of OPEC contributes to a more qualified understanding and contextualization of the events of 1973 as a not such an abrupt “turning point.”5

This article focuses on and contextualizes ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi’s economic thought in order to knit these historical and historiographical pieces together. I do not elaborate on Tariqi’s activities as Saudi expert, oil minister, and co-founder of OPEC, which have already been the subject of historical biography.6 Instead, I examine lesser-known aspects of Tariqi’s career following his dismissal from his ministerial position, focusing in particular on his role as an travelling oil expert and consultant to Arab governments on oil matters, as well as his work as an activist and sometimes controversial editor of the journal Naft al-‘Arab (Arab Oil). By the early 1970s, ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi no longer enjoyed a comfortable position in the Saudi government but was subject to political and financial pressures in running his consultancy business and journal.7 This in part accounts for Tariqi’s distinct position among those who struggled for the sovereign rights of decolonized countries over their natural sources and whom Christopher Dietrich has termed the “anti-colonial oil elites.” As Nelida Fuccaro’s analysis has explored, the first generation of “Arab oilmen” championed radical oil politics up to the mid-1960s.8 However, the following decade was marked by a new generation of more moderate oil technocrats. Through an examination of Tariqi’s role as an anticolonial oil expert and Arab oilman between the late-1960s and early-1970s, this article adds to our understanding of anticolonial elites and their connection to popular and grassroots radicalism. In doing so, I emphasize not only the continued role of first-generation experts like Tariqi, but also the enduring legacies of their economic, rather than political, ideas.

Back to topThe economic dimensions of oil prices

In September 1970, just four months before the Tehran agreement, the Libyan government successfully negotiated its concessionary agreements and was the first country to obtain a re-evaluated posted price, in addition to an increase in the tax rate on net income from 50 to 55 per cent. Helped by external consultants like Tariqi, Libyan Prime Minister, Mahmud al-Maghribi, a naturalized Libyan of Palestinian origin and Oil Minister ‘Izz al-Din al-Mabrouk, had taken advantage of the competition between the independent companies operating the Libyan fields and the Seven Sisters in the negotiations. They had also made the most of Libya’s geographical closeness to European markets and of the low level of sulphur content, which made Libyan oil a particularly valuable product for the European refining industry. The Venezuelan government unilaterally raised the rate of income tax on oil companies to 60 per cent in December 1970, just days before hosting the OPEC conference. At Caracas, OPEC members agreed to impose an increase in posted prices and a minimal tax rate of 55 per cent on the profits of the oil companies.

Arab oil experts were unsure how to respond to the outcome of the Tehran negotiations. The hesitating and successive views of anti-colonial experts like ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi evidence the transformation of their approach to oil issues. In the lecture he gave at the Nadi al-Istiqlal, ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi was critical of three major areas of oil strategy, while recognizing that the negotiators at Tehran had managed to get a share in the pricing decision process. First, he suggested that OPEC members had failed to provide support to Libya and Algeria in their upcoming negotiations on the prices of crude in the Mediterranean. OPEC had given a very restrictive meaning to decision No. 120 taken at Caracas in December 1970 by making their support conditional on both countries’ compliance with the prices agreed on at Tehran. However, as Tariqi reminded his audience, OPEC decision no. 120 stated that oil prices should be aligned with the highest posted price applied by any other member country. This included the Venezuelan price which was much higher than Gulf prices. Secondly, OPEC Gulf countries had failed to negotiate and reach agreement as a truly international organization, as had been envisioned by decision no.120 which had called for the creation of a committee of Gulf countries to carry out negotiations with oil companies. Instead, each member country had been left to reach agreement with the oil companies alone. This added to a lack of solidarity, as discussion around oil issues moved to an international forum and away from than transnational mobilizations that had occurred in the 1950s and 1960s. Thirdly, the Gulf governments agreed to a fixed period of price stability for five years, during which they would not claim any additional increases. Al-Tariqi and other anticolonial oil experts argued that this fixed period was excessively long, and that the governments should not have conceded more than three years, a criticism that was shared by officials in the Saudi government. Hisham Nazir, director of the Development Board who had begun his career at the Saudi Ministry of Petroleum during Tariqi’s tenure, similarly suggested that Oil Minister Ahmad Zaki Yamani could have pushed OPEC’s claims at Tehran much further.9

The same day that ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi delivered his lecture in Kuwait, the Algerian journal, El-Moudjahid, a mouthpiece for the Algerian government, published an article by Hasan Bahlul describing the Tehran agreement as a minimal achievement that should not be applied to the crude of Algeria and Libya. Echoing Tariqi’s approach, Bahlul began by outlining the “important results” of the agreement and duly praising them. However, the increase of oil prices agreed on at Tehran, despite being substantial, were deemed too modest in comparison with the inflation rate of manufactured goods. Bahlul insisted that Libya and Algeria maintain a similar position in oil negotiations that was distinct from that of the other two crude exporters in the Mediterranean, Iraq and Saudi Arabia. It is important to note here that Bahlul’s article was published two days before Libya finally revised its position in light of Tehran agreement’s gains and was entrusted by the other three countries with the task of negotiating on their behalf for the Mediterranean crude. In line with their country’s diplomatic stance, the editors of El-Moudjahid continued to emphasize the global impact of oil prices and the particular complexity of this issue for developing nations. However, they failed to address the growing discrepancy between the policies of oil-producing countries and those of their co-developing but non-oil-exporting counterparts. The export price of raw materials did not rise at the same pace as oil and gas prices, while the import of manufactured products by developing countries was impacted by the increase in oil prices, putting these nations in a difficult position.10

Later in 1971, Hasan Bahlul published an interview with ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi. The interview provided a means of promoting the efforts of Algeria and Libya in the struggle for economic independence and control of the oil industry, a few months after carrying out negotiations with foreign oil companies operating in their countries for the prices of the Mediterranean crude. In the interview, Tariqi described the Tehran agreement as a further positive milestone in a gradual and cumulative series of events that began in Tripoli in September 1970, where Libyan negotiators secured a 30% hike in the price per barrel. This series continued with OPEC’s decisions in Caracas in December 1970, which further solidified the position of Gulf countries, before culminating in the Tripoli agreement of April 1971.11 This narrative of events was supported by the Algerian government’s decision to nationalize its oil industry in February, and the continuing discussions in Libya over nationalization. The first stage of Libya’s oil nationalization was made public on December 7th, 1971 and couched in terms of a retaliation to the British Government’s failure to prevent Iran from occupying the islands of Abu Musa, Greater and Lesser Tunbs in the Gulf. From the perspective of Tariqi and his Algerian interviewer, Libya and Algeria were at the forefront of the Arab effort to achieve full economic independence. In contrast, the OAPEC countries of the Gulf were hindered by political divisions over the decision to allow Iraq to join, which left Libya and Algeria isolated and vulnerable to the advantages of imperialist countries. They also considered that the pro-Western policies of the Gulf’s monarchical states exacerbated this feeling of discomfort.

The most significant and long-lasting outcome of the anti-imperialist transnationalism championed by Tariqi and others was the eventual control over oil production through the nationalization of the oil industry in the 1970s in both Arab and non-Arab producing nations. Although he advocated a prudent policy of cooperation with Western companies instead of “jumping on the existing oil industry,” in order to get experience and “grow slowly” during the 1950s, Tariqi had changed his mind by the mid-1960s.12 Free from his ministerial reservations and increasingly concerned by the reluctance of foreign oil companies in the negotiations, Tariqi now advocated nationalization as a “national obligation” for Arab countries. He did not insist on the prerequisite of Arab unity and collective organization anymore. Instead, he now considered nationalization to be the most urgent priority for the Arab nation. From 1971, Tariqi’s magazine Naft al-‘Arab duly celebrated the decisions by the Algerian, Libyan and Iraqi governments.13

Before Algeria inaugurated a wave of nationalizations of the oil industry in Arab countries in 1971, oil-producing countries had no say in oil pricing. As Timothy Mitchell has argued, something equivalent to a “market price” of crude hardly existed before that.14 In the wake of the Second World War, a double pricing system had emerged for crude. Official or “posted” prices were the prices agreed upon by the oil companies to sell their crude and were approved by the European Cooperation Administration (ECA) for oil shipments to Europe. They were calculated according to a “netback system” that ensured that exports of Arabian crude to Europe would be sold at the same price as American competitors. This system of posted prices brought significant benefits to oil companies operating in the Middle East, particularly those with low production costs compared to their American counterparts and those producing low-sulphur Libyan and Algerian oil with minimal freight costs to European markets. Alongside the posted prices, there were also much lower and secret transfer prices between parent companies of shareholder firms.15

As demand for foreign oil in the USA decreased due to a system of quotas that had been imposed in 1959 and production increased globally, the importance of posted prices evolved in the 1950s to primarily serve as a fiscal tool.16 In the USA, oil prices were shaped by quotas on oil production and imports, which were determined by the federal government from 1959. Outside of the USA, crude was either transferred by the companies to their shareholders for refining and marketing, or sold among the major oil companies under long-term contracts. Oil-producing countries primarily generated revenue from oil through taxes imposed on each barrel, which were based on the “posted” price established by the companies to calculate the 50% they were required to pay.17

Until 1971, therefore, the tax rate was the primary means for oil-producing countries to increase their revenue from oil production without depleting their reserves. To many observers in the Middle East, the oil companies’ decision to reduce posted prices in 1959 had been taken as a deterrent to the oil experts planning to meet in Cairo to discuss the ways to increase the oil income of producing countries.18 The reductions prompted experts and officials like Tariqi to travel to Caracas to consult with their Venezuelan counterpart Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonzo. The Iraqi Prime Minister ‘Abd al-Karim Qasim invited the Gulf oil producing countries and Venezuela to convene in Baghdad, leading to the creation of OPEC in September 1960. From 1960, the issue of oil prices took precedence over the revision of the concession agreements and discussions about transnational schemes of development. Tariqi addressed this issue during his lecture at the second Arab Petroleum Congress in Beirut in October 1960. Based on his deliberately provocative calculations, he claimed that the pricing system had allowed oil companies to evade paying up to 5.5 billion dollars owed to Arab countries over the last 7 years.19

Since the 1950s, oil-trained experts like Tariqi were instrumental in deciphering the methods of oil pricing by the companies and making clear the gap between the companies’ actual profits on the one hand, and the posted price they unilaterally determined on the other hand. Tariqi was particularly proud of having uncovered how oil companies had taken advantage of discounted prices to calculate the tax owed to the Saudi and Kuwaiti governments in the early 1950s.20 While OPEC members struggled to compel the oil companies to restore crude prices to their pre-1960 levels, Tariqi put forward a number of solutions: curbing production, increasing participation in the oil industry in order to capture a bigger share of profit, nationalizing the industry, or increasing taxes on oil companies’ benefits. Tariqi often focused on the issue of price fixing, particularly as a short-term solution. As demonstrated by his February 1971 lecture, he increasingly centered his analysis on the exploitation of Middle Eastern oil by Western companies. He saw this exploitation as the driving force behind the history of oil prices since World War Two, despite the fact that the oil pricing system was originally established to serve the European markets after the war and resolve competition among oil companies by equalizing crude prices in Europe, regardless of origin.21 Before they reached a stalemate that led to eventual nationalization, oil negotiations such as those that took place between Algeria and France in 1970 were focused on posted and discounted prices. Tariqi was well aware of this, and he proposed new formulas for the fair pricing of Algerian and Libyan crude in May 1970.22

Experts like Tariqi did not question the pricing system as a whole. Instead, they called for its proper implementation by ending discounting and equalizing the prices of Arabian crude with those of equivalent crudes. In addition to their preoccupation with the global market, they defended the right for oil producing countries to follow the example set by Venezuela and fix the posted prices of crude. According to the numbers Tariqi put forward at the Nadi al-Istiqlal, Middle Eastern producing countries would have earned an additional $10.4 billion had they followed Venezuela’s example.23 Until 1971, he explained, prices had not been re-evaluated in light of the depreciation of the dollar and global inflation. This depreciation in the value of crude in the 1960s not only led to the debasement of oil purchasing power in relation to the manufactured goods imported by oil-exporting countries. It undermined the taxes collected by governments and the profits of nascent national oil industries as well.

However, the sustained rise in oil prices since 1970 presented a new challenge, as it would negatively impact the development of other developing countries that relied on importing oil and its derivatives. This was a challenge to the transnational concerns of Tariqi and other anti-imperialist experts like Nicolas Sarkis, a Syrian oil expert with advanced economic knowledge, holding a PhD in economics. Sarkis had founded the Journal of Arab Oil and Gas (Majallat al-bitrul wa-l-ghaz al-‘arabi) in 1965 and had had a transnational career similar to Tariqi’s, ranging from Algeria to Iraq. Tariqi and Sarkis proactively addressed the issue of rising oil prices and their impact on developing countries that relied on oil imports. They were vocal participants in discussions at the 1972 Arab Petroleum Congress, where this issue was discussed. Tariqi had close ties with Sarkis as they shared an office building and Tariqi contributed to Sarkis’s Journal of Arab Oil and Gaz. Meanwhile, Sarkis gave a lecture at the Kuwaiti Nadi al-Istiqlal in 1972.24

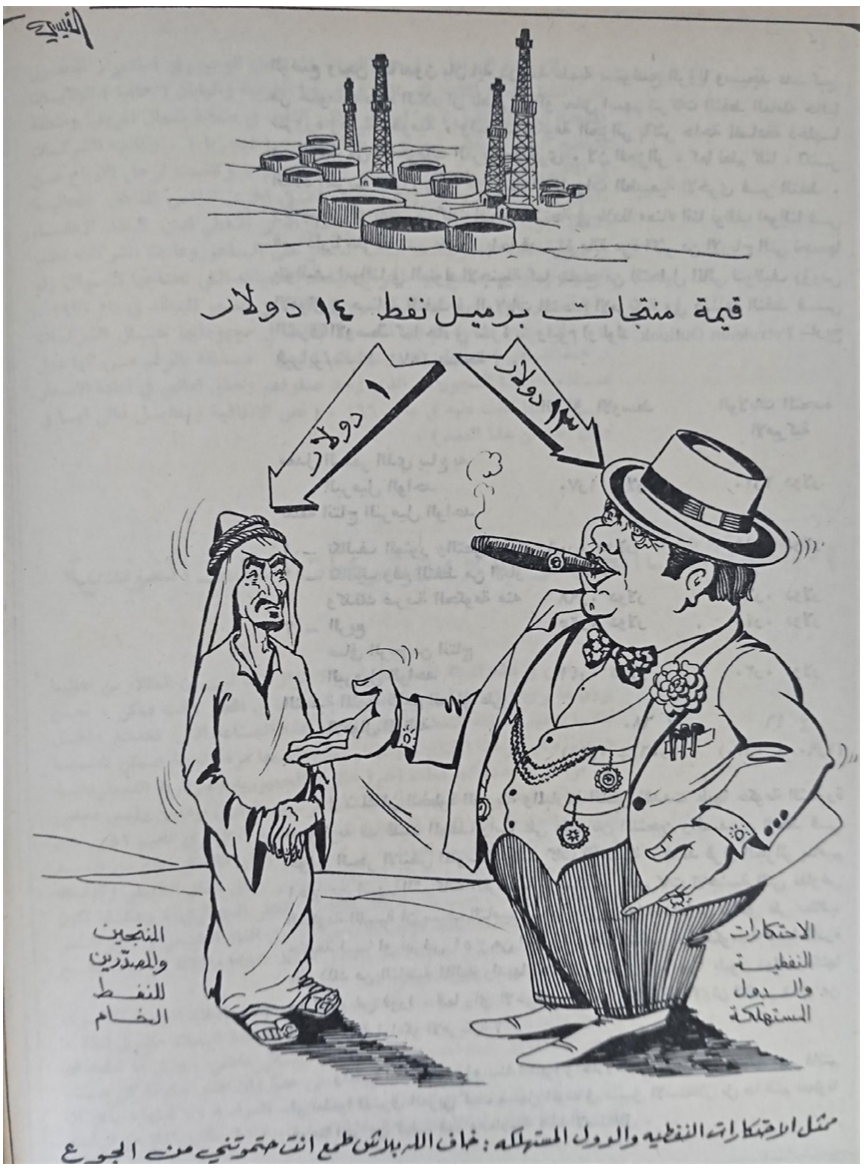

True to his earlier views, Tariqi did not approach the question of oil prices as a purely financial issue. Since the majority of the value added from oil was generated in developed countries where refining was still centralized and oil products were heavily taxed, these countries could paradoxically gain more from oil than their Middle Eastern suppliers. What is more, he argued, oil companies operating in the Middle East would invest much larger amounts in refining and downstream industries in Europe, American and Japan, than in the Middle Eastern fields which were already producing huge quantities at comparatively low costs. In his suggestions for new formulas for the “just” pricing of the Algerian and the Libyan crude in 1970, Tariqi had referred to a study by OPEC in 1969 which demonstrated the deeply unequal distribution of profits. Although, on average, the production costs accounted for only 2.7% (or $0.285) of the price of a barrel produced by an OPEC member in the late 1960s and the revenue collected by the producing countries’ governments only accounted for 7.9% of this price, the consuming countries’ governments would collect taxes accounting for 47.5% (or $10.74) of the same barrel’s price.).25 [Fig. 1] Inequality in the distribution of profit was a direct result of the poorly developed industry in producing countries. Underdeveloped industry prevented these countries from capturing more than a limited benefit from their own resources, particularly as these resources were raw materials. As he put it in February 1971, producing countries of the Middle East thus had to “to grasp the problems and intricacies of oil industry” as a whole, not to focus on the issue of price obsessively. By the early 1970s, however, Tariqi’s lecture makes clear that this issue had come to encapsulate the challenges of development and independence for countries whose participation in globalization was, to a considerable extent, driven by oil. Similar to Tariqi’s arguments about deposits in foreign banks, his persistent preoccupation with the interconnection between financial matters and a more comprehensive perspective on the global oil economy, highlights his economic approach and explains why he and similar experts and officials repeatedly vacillated between strategies that emphasized the oil industry, financial, national, Arab nationalist or transnational interests.

Popularizing an anti-imperialist oil economy

‘Abdallah al-Tariqi was not a newcomer to Kuwait in 1971. His mother-in-law and the mother of his two eldest brothers was Kuwaiti. He spent some time studying at the Kuwaiti Ahmadiyya School with one of his brothers in the 1920s, while his father Hamud would come and go for caravan trade between al-Zulfi (his place of birth in Najd) and Kuwait. Tariqi probably left Kuwait in 1929 for India where he worked as an apprentice alongside the Arab merchants of Mumbai, before moving to Cairo in 1933 to pursue his studies. In his role as a minister for the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Tariqi’s thoughts and concerns regarding oil always included Kuwait, since both countries share a common field in what was called the Neutral Zone. Tariqi played a significant role in negotiating the agreement with the Japan Petroleum Trading Company that resulted in the exploitation of shared oil under unprecedented economic and industrial conditions.26 This agreement would later be regarded as a major turning point by OPEC officials.27

After his dismissal from his position as minister in Saudi Arabia 1962, Kuwaiti companies like Kuwait Airways were major advertisers in the magazine he edited, Naft al-Arab until 1971.28 Yet, as he grew more critical of Arab governments and OPEC’s strategy during the 1960s, Tariqi’s radical views were not uncontroversial in Kuwait. In 1966, there was a dispute over Tariqi’s role as an advisor to the Kuwaiti government during the renegotiations of the Kuwait Oil Company concession agreement and its approval by the Kuwaiti Parliament. Some government officials, employees of the Kuwait National Petroleum Company, and others sought to have Tariqi dismissed or to balance his influence with that of a more moderate oil expert like the Iraqi Nadim al-Pachachi.29

Since the beginning of his career as an oil official and expert, Tariqi embodied the anti-imperialist economic and legal aspirations of a globalized world. He turned to Venezuela as an early model for oil legislation and economics in Arab countries, especially Saudi Arabia. In charge of monitoring oil companies in the Eastern province after his return to Saudi Arabia in 1948, he used Venezuela’s example in order to advocate for the implementation of the 50-50 system in the Kingdom. In 1951, it is likely that Tariqi was the Kingdom’s representative to the Caracas Petroleum Convention where oil prices were already a major topic of discussion, and the challenge presented by the opposition of powerful American and British oil companies provided a shared experience.30 In 1960, he got in touch with his Venezuelan counterpart, Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonzo, before going on to play a role in the creation of OPEC.31

The Arab Petroleum Congresses provided a suitable platform for Tariqi to express his ideas and challenge the power of oil companies. In 1959, at the first Arab Petroleum Congress in Cairo, Tariqi and Frank Hendryx, a prominent lawyer and oil expert whom he had recently recruited to work with him in Saudi Arabia, sparked intense debates by promoting the revision of concession agreements and the regulation of production to raise prices.32 Following his dismissal from the Saudi Oil Ministry in 1962, Tariqi continued to play the role of an oil advisor and a populariser of oil issues in his journal Naft al-‘Arab and in his lectures and consultancy work. His staunchly critical and often provocative views continued to provoke the anger of his opponents and the governments he often criticized, such as Saudi Arabia. In 1970, a year before the lecture in Kuwait, Tariqi had to move his office from Beirut to Cairo because the Lebanese government, under pressure, had prevented him from entering the country.33

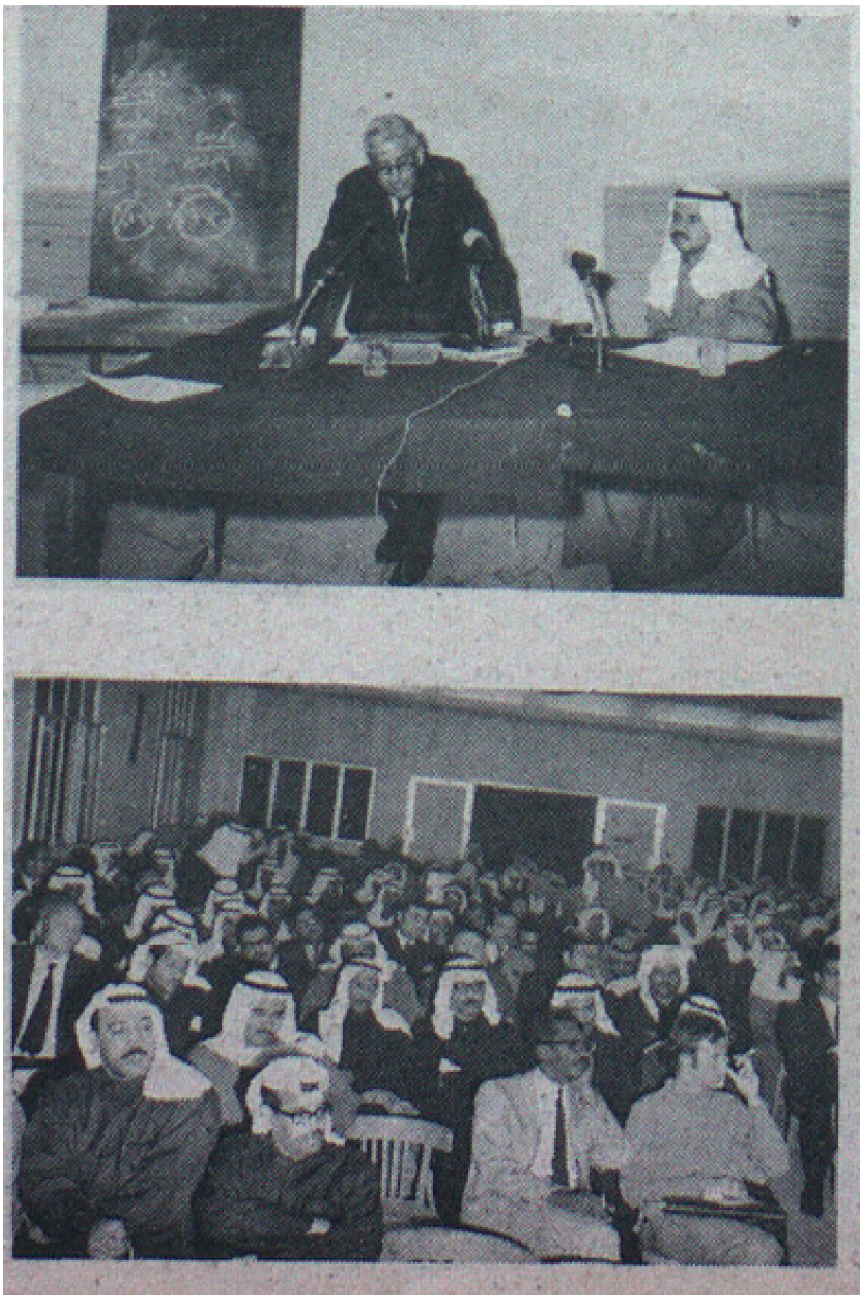

Tariqi ceaselessly emphasized the economic dimension of anti-imperialism, even while vocally opposing conservative Arab governments aligned with Western policies in the region, and passionately advocating the Palestinian cause. The struggle against imperialist countries supporting Israel and opposing Arab interests was primarily an economic struggle or, in his words, “the Arab nation possesses a weapon which is among the sharpest weapons that can be used against its enemies.”34 Even his advocacy of oil as a “weapon” was supported by data tables and graphs based on accurately sourced figures (OECD, OPEC, Oil and Gas Journal, Petroleum Intelligence Weekly, etc.). His articles typically included schemas in addition to more complex lists of figures and diagrams. Pictures of his lecture at the Nadi al-Istiqlal show him standing in front of a blackboard covered in signs, letters and numbers. [Fig. 2]

‘Abdallah al-Tariqi exemplifies the emergence of technical knowledge about the oil industry as an instrument to devise oil policy and support the producing countries’ position during negotiations with not-yet-nationalized and still-foreign-owned oil companies. In highlighting the legal dimension of this process, Christopher Dietrich has convincingly argued that such knowledge was the product of transnational networks of expertise within decolonizing countries and across international institutions. Although he would sometimes criticize OPEC strongly, the organization was still instrumental in producing many studies and data that Tariqi himself used extensively in his lectures and articles. This knowledge about oil was by no means specific to anti-colonial and Middle Eastern elites however. While Nathan Citino has argued that “internationalist oilmen” have played a critical role in shaping an unified agenda for America’s domestic and foreign policy about oil affairs in the Middle East during the Cold War, Timothy Mitchell has emphasized the intellectual transformations that supported these experts’ authority during the 1950s when an abundance of oil resources and cheap prices led to a new conception of the “economy” and of the role of experts in interpreting processes of unlimited growth. Knowledge about oil was subject to both economization and inflationary demand and supply after World War Two. In the United States and Western Europe, the need for oil expertise on the issues of oil availability and prices became even more pressing, as the oil crisis unfolded in the 1970s. In Middle Eastern oil-producing countries, experts’ predictions of economic growth secured their long-term employment and their ideas were used politically to legitimize the government’s control over oil profits and the nationalization of the oil sector.35

Tariqi’s lecture touched on the challenges of the position of the oil expert in the early 1970s, in his attempts to differentiate himself from second-generation oil experts on oil-related matters and reconcile the national and transnational oil strategies he had long advocated for. Although Tariqi had adopted a more overtly political attitude once he was dismissed from his ministerial position in Saudi Arabia in 1962, as Stephen Duguid has noted, he was still committed to an economic understanding of oil issues. He strove repeatedly to make these issues understandable in order to recommend strategies that fitted developing countries of the region, and rally supporters of Arab nationalism.

Tariqi’s articles and public lectures demonstrate the difficulty of making the economic dimension of anti-imperialism comprehensible for a wide audience. Existing scholarship towards prominent anti-imperialist elites and decolonization reverberates this difficulty. It is often narrow in its focus on the political and cultural aspects within the realm of the oil economy. By reevaluating the economic dimension of anti-imperialist mobilizations and its complexities, we gain a deeper understanding of the perspectives of “anti-colonial oil elites” (as described by Christopher Dietrich) and their reception in countries like Kuwait. This sheds light on how both experts and their audience navigated the challenges posed by oil globalization and its impact on anti-imperialist ideas of economic development.36 Although recent scholarship has also echoed the pessimistic views of anti-imperialist experts like Tariqi over political and cultural decline of the left in the Arab world, we should not overlook the legacy of the specifically economic dimension of anti-imperialism, despite the bitterness of some of Tariqi’s assessments in the 1970s and the numerous regional failures he encountered while addressing the oil industry in developing Arab countries.37

Back to topThe economic dimension of Arab oil transnationalism

Similar to the way in which Tariqi repeatedly returned to political considerations in his lecture, the current literature on the struggle for independence from imperial domination by developing countries during the 1960s and 1970s and on the opposition to the dominance of foreign oil companies only briefly touches upon economic issues. The political and social aspects of anti-imperialist mobilizations receive more attention than the economic aspects, which are usually treated as mere background information rather than as independent issues. While several insightful studies have focused on the transnational and South-South dimensions of these movements, political and cultural approaches dominate the study of developing countries and anti-imperialism during the 1960s and 1970s. The scholarship on Latin America, due to the influence of economists like Raúl Prebisch, is a rare exception to this bias.38

The lack of consideration given to economic approaches is even more noticeable in the scholarship on oil affairs. Even today, the “shock” of 1973 is primarily perceived as a political decision made by the governments of Arab oil-producing countries. Arab experts and officials sought to separate the economic reasons behind the price issue from the political motivations that led to the embargo, and from the “energy crisis” narrative presented by North American officials. As Nicolas Sarkis explains in detail, oil prices were purely an economic issue tied to global inflation, the depreciation of the dollar, the peak of oil production in the USA, and the unilateral methods for determining oil prices until the early 1970s. Arab experts attempted to disconnect these economic factors from political decisions, such as the embargo.39

The scholarship not only privileges political and cultural approaches to anti-imperialist mobilizations but has also been subject to a process of politicization which has resulted in economic issues like production levels, pricing formulae and commercialization of raw materials being viewed as the purview of a limited group of experts and secondary to broader political topics. In this regard, the existing scholarly literature is repeating the attitudes documented in contemporary sources. In the Middle East, the 1960s and early 1970s was driven by struggles for independence and state-building. Great Britain embarked on a large withdrawal from the Gulf countries after 1967, and many countries underwent political transformations such as Algerian Independence in 1962 and the 1969 Libyan Revolution, which both brought staunchly anti-imperialist elites to power. Britain had terminated its protectorate over Kuwait in 1961, and the very name of the society that hosted the lecture of February 1971 was a present reminder to ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi and his audience that independence was a continuing struggle. These ongoing processes of decolonization provided not only opportunities but also bargaining power to oil-producers.

When it is not ignored altogether, the economy is usually addressed in the literature about developing countries of the 1960s and 1970s as context in which politics takes place rather than as a primary focus of political mobilization or, as Mary Nolan put it, “one possible, but seldom the primary arena of politicization.”40 Although he primarily focuses on its legal dimension, Dietrich’s book on the “economic culture” of decolonization is a notable exception. Despite being key drivers of transnational movements, the economic aspects of anti-imperialist struggles and connections have often been overshadowed in the historical analysis, which primarily focuses on the political and cultural dimensions. However, many anti-imperialist programs, including those for economic reforms, were central to these movements and included demands for fair distribution of oil wealth. Strikes, unionism, and nationalizations of key industries also formed an important part of the anti-imperialist, progressive and leftist agenda. Furthermore, the economic context was instrumental in shaping the emergence of new generations of political leaders, militants, and experts.41

In Saudi Arabia as elsewhere in the Gulf, oil played a key role in motivating political demonstrations. In the Eastern Province of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, oil workers launched the first major strikes in the region’s history, driven by both economic demands such as better salaries and working conditions, as well as political demands. Beginning in 1945, one year prior to the major strike in Iranian oilfields, two years before similar strikes in Iraq, and two years after strikes carried out by Bahrain Petroleum Company workers, a series of strikes mobilized Saudi and non-Saudi Arab workers in the oilfields, motivated by the demand for better salaries and benefits from the American oil company, Aramco, which had been operating the Saudi oilfields since 1933. Aramco had implemented discriminatory labour practices and segregated its labour force, not unlike the labour organization used by British-managed companies in other Gulf countries, such as Iran and Iraq. The working and living conditions of Arab workers was vastly inferior to the conditions enjoyed by the American, European and Indian employees living in neighbouring camps that were separated and fenced-off. A growing number of migrant workers brought with them anti-imperialist and organizational ideals, along with a transnational outlook. For many activists, working in the oil industry was a formative experience.42

Despite his reticence on the topic, Abdallah al-Tariqi had observed a series of strikes by Arab oil workers since his return to Saudi Arabia from the USA in 1948. These strikes slowed down after 1956, when the Saudi government began to ban strikes and unions. During the major strike of 1953, around 13,000 of the company’s 15,000 workers went on strike, directing their grievances primarily at the oil company. Workers demanded better salaries and living conditions, and political demands were secondary. In 1956, oil workers in Saudi Arabia and in neighbouring oil-producing countries went on strike again. This time, economic grievances were combined with overtly progressive, nationalist and anti-imperialist political demands in support of Egypt during the Suez crisis. Although both strikes and unions were banned by the government in Saudi Arabia and Bahrain (but not in Kuwait), support for Arab nationalist causes and the Palestinian movement regularly sparked mobilizations that targeted Western policies, Western-backed authoritarian regimes in the Gulf, and the foreign oil companies that fuelled imperialism. Despite their suppression by the late 1960s, these mobilizations compelled national bureaucracies and foreign oil companies to devise reforms for working and living conditions and for the national economy. Oil played a crucial role in shaping the development of Middle Eastern states, before becoming the windfall that ultimately led to the downfall of revolutionary nationalism in the region after 1967, and the strengthening of authoritarian and monarchical regimes in the 1970s with the support of state-owned oil companies.43 Therefore, the discussion about the oil economy in 1971 was not solely a theoretical or elitist issue. It facilitated transnational connections for countries like Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, whose revolutionary potential until the early 1970s is being rediscovered, albeit from primarily a political (ideological) perspective.

It is likely that ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi observed these popular movements supportively, as one of the first Saudi geologists, who had graduated from Texas University under a Saudi scholarship and trained at Texaco before returning to Saudi Arabia and taking a position at the Ministry of Finances as an expert for oil and minerals. Tariqi seems to have conceived of his activities as part of a high-level and elite struggle taking place alongside the mobilization of oil workers. While Tariqi’s support for progressive causes was clear, he was careful not to comment on oil worker strikes in his articles while he was still in office in Saudi Arabia, navigating between King Saud and Crown Prince Faisal’s patronage.44 In private conversations however, Tariqi made clear his criticisms of Aramco’s policies towards Saudi workers. His friendship with progressive bureaucrats and more vocal opponents to Aramco’s discriminatory practices like ‘Abd al-‘Aziz Ibn Mu‘ammar (d. 1984) was also well-known. A close confidant to King Saud, Ibn Mu‘ammar was charged by the Saudi monarch with the investigation into the conditions of Aramco’s workers in the wake of the 1953 massive strike. He participated in the establishment of the National Reform Front, which criticized the imperialist policies of the American company and called for broader economic and political reforms in the country.45 By the mid-1960s, after Tariqi had left his government position, the state repression and incentives offered by oil companies effectively suppressed strikes and other forms of mobilization by oil workers. By that time, Ibn Mu‘ammar had also been ousted from his position at the Ministry of Finance’s Labour Office in Dammam and from the Saudi Court. In 1963 Crown Prince Faisal recalled Ibn Mu‘ammar from his post as ambassador to Switzerland and put him under arrest.46

One rarely finds references to oil strikes and workers’ struggles in Tariqi’s interviews and writings, either before or after his progressive views resulted in the loss of his ministerial position in Saudi Arabia in 1962. However, activists who had close connections to oil workers and union leaders remained among Tariqi’s core audience. For example, the progressive and Arab nationalist Kuwaiti leader, Ahmad al-Khatib, easily recognizable in his Western suit, was seated in the front row of the Nadi al-Istiqlal in February 1971, demonstrating Tariqi’s continued appeal. [Fig. 1]. In his Memoirs, which unfortunately do not cover the period after 1967, al-Khatib pays tribute to the role Tariqi played in 1965 when the Kuwaiti National Assembly refused to ratify the arrangement devised by OPEC and oil companies on the expensing of royalties. Many nationalist MPs had discussed the issue of royalties with ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi and took the opportunity to raise other complex topics, such as production levels, tax payments, and employment and working conditions for Kuwaitis at the Kuwait Oil Company.47

‘Abdallah al-Tariqi and most oil experts at the time spoke of “developing” countries as distinct from “industrialized” or already “developed” countries. However, the historical paths of Arab oil-producing countries were intimately connected to what today we might term the making of the “Third World” as a community of countries opposing imperialism. For countries like Algeria, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia, solidarity among developing countries was both a result of and a motivation for building connections with non-Arab countries, as evidenced by their participation in the Arab Petroleum Congresses since 1959 and the early successes of OPEC. Tariqi himself drew inspiration from the experiences of non-Arab oil-producing countries, such as Venezuela, which he visited early in his career. In his lecture at the Nadi al-Istiqlal and in other writings, he often referenced the economic experiences of Latin America and Asia as a point of comparison to the policies developed in Arab countries.

Transnational anti-imperialism was not systematically opposed to national strategies in decolonizing countries, and Tariqi certainly did not see it that way. On the contrary, it could be instrumental in state-building in countries with strongly nationalist governing parties like Algeria.48 As highlighted by James Byrne, the emphasis on global connections and transnationalism sometimes resulted in the strengthening of national sovereignty and statehood as guiding principles of post-independence policies.49 Christopher Dietrich has argued that the very principle of “sovereign rights” played a crucial role in the formation of a transnational group of “anti-colonial oil elites,” who sought national independence for their countries in a rapidly globalizing economy.50 The impact of these connections between developing countries in the South went beyond shaping their political relationships and development paths. They influenced the global order and its institutions during the Cold War and challenged the dominance of the superpowers and their European colonial allies. The establishment of OPEC, initiated by ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi and his Venezuelan colleague Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonzo in 1960, and the demand for a New International Economic Order were the epitome of Third-Worldism in the realm of economics, advocated by countries that produced raw materials.51

However, in Gulf Arab countries such as Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, linking national and transnational goals was not a straightforward task when addressing economic objectives. ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi had been advocating schemes of joint-development based on oil production for a long time. He was not alone and the Arab Petroleum Congresses, which had taken place since 1959, were the main venues for the dissemination of such proposals by Tariqi and other oil experts like Nicolas Sarkis. Oil was a key component of transnational and pan-Arab economic development plans, which focused on heavy industries relying on oil energy, oil transportation via pipelines and tankers, and the production of oil derivatives.52 It could have been the cornerstone of solidarity between oil-producing and non-producing countries through cooperation between countries rich in oil but lacking in manpower on one hand and countries rich in manpower but lacking in oil on the other.53

When they addressed the oil industry specifically, Tariqi, Sarkis, and others prioritized righting what they considered unfair rules, which had been set by big foreign companies and buttressed by infamous concession agreements. The main points of contention were levels of production, the pricing of crude oil, and the payments to the governments of producing countries in the form of taxes. These oil experts considered true independence and anti-imperialism to be primarily economic issues, embedded in the working of the global market of raw materials. Political and social projects came only second in their lectures and articles, although they were far from absent. At the Nadi al-Istiqlal, for example, once he had explained the intricacy and urgency of crude prices, ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi went on to explain why, in his view, the Gulf oil producers should keep the huge amounts of money they received from the oil companies for themselves, or deposit them in foreign (i.e., English) banks which had low rates of interest and would benefit foreign economies. Instead, Tariqi argued they should invest oil revenues in their own industries or use them to defend Arab countries, especially Palestine, from the “colonialism” of Western countries, Israel and Iran.

As this discussion suggests, prioritizing the use to which oil revenues should be put was not a clear cut. The growth of national industry, supported by oil revenues and technological training, was in conflict with the transnational development plans Tariqi had been advocating for. As Tariqi had pointed out, the scheme devised by OPEC members in Tehran was primarily an international arrangement, in which the Gulf countries negotiated with foreign companies independently from their Mediterranean partners. Each country sought to maximize its oil revenues on the global market and the allocation of raw materials would gradually move away from transnational efforts towards more selective and international cooperation.

At the Nadi al-Istiqlal, ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi mocked the “theatrical duel” between governments of the Gulf producing countries and the foreign oil companies. He emphasized that in return for agreement on the price and tax increases, the companies had insisted that no alterations would be made to the agreement for the following five years. The oil companies also required the Gulf nations to pressure the Mediterranean producers to negotiate on similar terms in the upcoming negotiations to prevent Libya and Algeria from gaining an advantage over other oil-producing countries by securing more favourable terms. The Tehran agreement, Tariqi told his audience, guaranteed access to alternative sources of oil for the foreign oil companies and strengthened their position as they opened negotiations with Libya and Algeria over the price of Mediterranean crudes. The companies had in fact managed to divide OPEC countries. However, Tariqi admitted that in the Tehran agreement, the Gulf producers finally obtained a role in the pricing decision-making process, two and a half years before Arab oil ministers made the historic decision in 1973 to raise prices unilaterally. Faced with the threat of unilateral decisions made by OPEC Gulf members, including Iran, foreign oil companies yielded to their demands and consented to a hike in posted prices of more than 35%, along with an annual increase to offset inflation. They also agreed to differentiate crude qualities and set varying premiums, favoring Arabian crudes, and set the tax rate at 55%.

Back to topConclusion

By February 1971, OPEC members had already started to regain control over prices from foreign oil companies. This presented a challenge not only to the ideas and plans that had been formulated during the 1960s by anti-imperialist experts and activists such as Tariqi and those present at the Nadi al-Istiqlal, but to the very role of transnational oil expertise. Increased oil prices and greater sovereignty over price-fixing decisions price jeopardized transnational schemes of cooperation and economic development, stirring competition both among oil producing countries, and between oil producers and the developing countries which exported raw materials.54 More inclusive schemes for industrial development gradually receded in importance, while financial concerns became paramount in determining the ways in which oil-producing countries participated in globalization.

By 1973, Arab oil producing countries had almost completed their control over oil prices and the oil industry. The historic decisions of October 1973 had established the complete sovereignty of oil producing countries over oil prices, while the wave of nationalizations that begun with Algerian nationalization in 1971 and ended with Kuwait in 1975, was well underway. This prompted both activists and officials to devise solutions for the development of oil-importing countries, particularly African nations. Due to its early independence from Great Britain in 1961 and strong Arab nationalist and anti-imperialist movements and organizations such as the Nadi al-Istiqlal, Kuwait was once again at the forefront. The Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development was founded as early as 1961 and distributed aid to non-Arab countries as well. During a summit in Algiers in November 1973, the heads of Arab states committed to providing both oil supplies and financial and technical aid to African States. In 1975, the Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa was inaugurated in Khartoum. Saudi Arabia and Kuwait were the main contributors. Yet, bilateral agreements shaped according to national interests channelled most of the aid.55

This article has focused on transformations already underway before 1973 in order to engage with the issue of oil prices and consider what this political and economic issue entailed for oil experts and their audiences. Discussions on oil prices in 1971 were not limited to a small group of educated experts and activists. They reflected and supported the broader cultural and political anti-imperialist movements of the 1960s. Tariqi’s own personal experience and the presence of notable figures from Kuwaiti progressive movements such as Ahmad al-Khatib at his lecture in Kuwait in February 1971, demonstrate the historical roots of such discussions in the long history of oil transformations and struggles in producing countries. Strikes for transnational causes, such as Palestine, and the demands of workers for very tangible benefits such as salaries and housing, oil embargoes, and debates about oil-driven development in international congresses and conferences of the 1950s and the 1960s were part of a common historical context for these struggles. The prohibition of trade unions in many Arab countries, growing political authoritarianism, and the replacement of Arab workers by Asian “temporary” workers would make Tariqi and others’ ideas gradually invisible even before the neoliberal turn in the 1980s took hold in the Middle East. At the same time, the failure to bring their long-advocated plans for international cooperation cum national development to fruition added to their disillusionment with their respective States’ economic strategies and increased competition between producers. Tariqi’s audience and his colleagues experienced the global “left-wing melancholia.”56 Despite this, they did not abandon their advocacy efforts. In fact, their legacy was far from lost. As argued by ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi in his lectures, articles, and historically-framed overviews, the gradual recapture of control over oil prices and the subsequent nationalizations in countries such as Algeria and Kuwait were tangible outcomes of their anti-imperialist advocacy. These events, along with the growing awareness among citizens in oil-producing countries, reflected the history of progress towards their goals of anti-imperialist economic reform.

- 1. ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi, “Ayna zahabat ‘uquluna?” [Where have our minds gone?], al-Tali‘a, n°317, 6/03/1971, 8-11.

- 2. Giuliano Garavani, The Rise and Fall of OPEC in the Twentieth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019); Javier Blas and Jack Farchy, The World for Sale: Money, Power and the Traders Who Barter the Earth’s Resources (London: Penguin Books, 2021).

- 3. Vernie Oliveiro, “The United States, Multinational Enterprises, and the Politics of Globalization,” in N. Ferguson, Ch. S. Maier, E. Manela and D. Sargent (eds.), The Shock of the Global: The 1970s in Perspective (Cambridge Mass.: Belknap Press, 2011), 143-155.

- 4. Adam Hanieh, Money, Markets and Monarchies: The Gulf Cooperation Council and the Political Economy of the Contemporary Middle East (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), chap. 2; Niall Ferguson, “Crisis, What Crisis? The 1970s and the Shock of the Global,” and Daniel J. Sargent, “The United States and Globalization in the 1970s,” both published in N. Ferguson, Ch. S. Maier, E. Manela and D. Sargent (eds.), The Shock of the Global: The 1970s in Perspective (Cambridge Mass.: Belknap Press, 2011), 1-21 and 49-64.

- 5. Elisabetta Bini, Giuliano Garavini and Federico Romero (eds), Oil Shock: The 1973 Crisis and Its Economic Legacy (London: I.B. Tauris, 2016), 4.

- 6. Stephen Duguid, “A Biographical Approach to the Study of Social Change in the Middle East: Abdullah Tariki as a New Man,” International Journal of Middle East Studies, vol. 1, n°3, 1970, 195-220.

- 7. Muhammad ‘Abdallah al-Sayf, ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi: Sukhur al-naft wa-rimal al-siyasa (Beirut: Riad El-Rayyes Books, 2007).

- 8. Nelida Fuccaro, « Oilmen, Petroleum Arabism and OPEC: New political and public cultures of oil in the Arab world, 1959-1964,” in Claes Dag Harald and Garavini Giuliano (eds.), Handbook of OPEC and the Global Energy Order (London: Routledge, 2020), 15-30.

- 9. British Embassy, Jeddah, 24/03/1971, Foreign Office Records (Kew Gardens), FCO 8/1756.

- 10. Hasan Bahlul, “Muhadathat al-bitrul fi Tahran: al-Sharikat al-bitruliya tardikhu li-shurut Munazzamat al-Duwal al-Musaddira li-l-bitrul” [Oil Negotiations in Tehran: Oil Companies yielded to OPEC’s conditions], El-Moudjahid, n°548, 21/02/1971, 12-13.

- 11. Interview with El-Moudjahid, by Hassan Bahlul, 28/11/1971, in ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi, al-A‘mal al-kamila, edited by Walid Khadduri (Beirut: Markaz Dirasat al-Wahda al-‘Arabiyya, 2005), 737-743.

- 12. Petroleum Week, 20/06/1958, 40, quoted by Stephen Duguid, “A Biographical Approach…,” 205.

- 13. ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi, “Ta’mim sina‘at al-bitrul al-‘arabiyya: Darura qawmiyya” [The Nationalization of Arab Oil: a National Obligation], Dirasat ‘arabiyya, n°7, May 1965, in al-Tariqi, al-A‘mal al-kamila, 158-178.

- 14. Timothy Mitchell, Carbon Democracy: Political Power in the Age of Oil (London: Verso Books, 2011), 232-233.

- 15. Nuno L. Madureira, “Squabbling Sisters: Multinational Companies and Middle East Oil Prices,” Business History Review, vol. 91, n°4, 2017, 681-706.

- 16. Robert Mabro, “The International Oil Price Regime: Origins, Rationale, and Assessment,” Journal of Energy Literature, vol. 11, n°1, 2005, 3-20.

- 17. Garavani, The Rise and Fall of OPEC, 54-62 and 74-75.

- 18. Hisham Nazer et Muhammad Jukhdar, “Oil prices in the Middle East,” Middle East Economic Survey, 23/09/1960, quoted in David Hirst, Oil and Public Opinion in the Middle East (London: Faber and Faber Ltd, 1966), 43-44.

- 19. Garavini, The Rise and Fall of the OPEC; Report by A. J. E. Eden, British Ambassador, 25/10/1960, quoted in Anita Burdett (ed.), OPEC: Origins and Strategy, vol. 2 (London: Archives Editions, 2004), 128-138.

- 20. Interview of ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi, Majallat al-Bitrul wa-l-ghaz al-‘arabi, n°6, 1966, in al-Tariqi, al-A‘mal al-kamila, 208-215.

- 21. Madureira, “Squabbling Sisters.”

- 22. ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi, “al-As‘ar al-lati yajib an yuba‘ biha al-Naft al-Libi wa-l-Jaza’iri” [The prices Libyan and Algerian oil should be sold for], Naft al-Arab, vol. 5, n°8, May 1970.

- 23. al-Tariqi, “Ayna zahabat ‘uquluna?”

- 24. Bahi Muhammad, “al-Mu’tamar al-‘arabi al-thamin li-l-bitrul,” El-Moudjahid, n°615, 04/06/1972, 6-9; author’s interview with Nicolas Sarkis, Paris, 20-04-2019; Nicolas Sarkis, “Musharakat al-Duwal al-‘Arabiyya fi Imtiyazat al-bitrul” [Participation of Arab Countries in Oil Concessions], al-Tali‘a, n°401, 25/11/1972, 8-9.

- 25. al-Tariqi, “al-As‘ar al-lati yajib an yuba‘ biha”.

- 26. ‘Abd al-‘Aziz Muhammad al-Dakhil, “‘Abdallah al-Tariqi wa-l-naft wa-l-watan,” al-Mustaqbal al-‘arabi, n°226, 1997, in al-Tariqi, al-A‘mal al-kamila, 88-89 ; interview with Akhbar al-bitrul wal-l-ma‘adin, n°2, 1961, in al-Tariqi, al-A‘mal al-kamila, 120.

- 27. OPEC, Public Relations Department, Radical Changes in the International Oil Industry During the Past Decade, IVth Arab Petroleum Congress organized by the Secretariat General of the League of Arab States (Geneva: OPEC, 1963), 7.

- 28. E.g., Naft al-‘Arab, n°12, vol. 6, 1971.

- 29. British Embassy, Kuwait, to Oil Department, Foreign Office, London, 04/09/1966 and 24/10/1966, Foreign Office Records (Kew Gardens), FO 960-15; ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi replying to the editors of the Kuwaiti al-Ra’i al-‘amm, Majallat al-Bitrul wa-l-ghaz al-‘arabi, n°6, 1966, in al-Tariqi, al-A‘mal al-kamila, 208-215.

- 30. Mazin al-Banduk, “Abu al-Ubek: ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi,” al-Jil, n°12, 1997, in al-Tariqi, al-A‘mal al-kamila, 75; ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi, “Muzzamat al-duwal al-musaddira li-l-bitrul: li maza unshi’at? Wa ma hiya al-ahdaf al-lati haqaqatha munzu insha’iha?,” Majallat al-Bitrul wa-l-ghaz al-‘arabi, n°3, 1965, in al-Tariqi, al-A‘mal al-kamila, 201-202 ; ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi replying to the editors of the Kuwaiti al-Ra’i al-‘amm, Majallat al-Bitrul wa-l-ghaz al-‘arabi, n°6, 1966, in al-Tariqi, al-A‘mal al-kamila, 211.

- 31. Abdallah al-Tariqi, “Muzzamat al-duwal al-musaddira li-l-bitrul,” Majallat al-Bitrul wa-l-ghaz al-‘arabi, n°3, 1965, in al-Tariqi, al-A‘mal al-kamila, 203.

- 32. Juan Carlos Boué, “The Road not Taken: Frank Hendryx and the proposal to restructure petroleum concession in the Middle East after the Venezuelan pattern,” in Claes and Garavini (eds.), Handbook of OPEC, 266-277.

- 33. al-Sayf, ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi, 256.

- 34. ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi, “al-Bitrul al-‘arabi: Silah fi-l-ma‘raka [Arab Oil: A Weapon in the Battle],” (Beirut: Munazzamat al-Tahrir al-filastiniyya, 1967) in al-Tariqi, al-A‘mal al-kamila, 967.

- 35. Nathan J. Citino, “International Oilmen, the Middle East, and the Remaking of American Liberalism, 1945-1953,” The Business History Review, vol. 84, n° 2, 2010, 227-251; Mitchell, Carbon Democracy, 109-143; Rüdiger Graf, Oil and Sovereignty: Petro-Knowledge and Energy Policy in the United States and Western Europe in the 1970s (New York: Berghahn, New York, 2018).

- 36. Christopher R. W. Dietrich. Oil Revolution: Anticolonial Elites, Sovereign Rights, and the Economic Culture of Decolonization (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

- 37. Laure Guirguis, “Introduction” in Guirguis L. (ed.), The Arab Lefts 1950s-1970s: Transnational Entanglements and Shifting Legacies (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020), 1-17.

- 38. Samantha Christiansen and Zachary A. Scarlett, “Introduction,” in Christiansen S. and Scarlett Z. A. (eds.), The Third World in the Global 1960s (New York: Berghahn Books, 2013), 1-20.

- 39. Nicolas Sarkis, Le pétrole à l’heure arabe: Entretiens avec Eric Laurent (Paris: Stock, 1975), 39-77; Mitchell, Carbon Democracy, chap. 7; Giuliano Garavini, After Empires: European Integration, Decolonization and the Challenge from the Global South (1957-1986) (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 162-171.

- 40. Mary Nolan, “Where was economy in the global sixties?” in Chen Jian, Martin Klimke, Masha Kirasirova, Mary Nolan, Marilyn Young, and Joanna Waley-Cohen (eds), The Routledge Handbook of the Global Sixties: Between Protest and Nation Building (New York: Routledge, 2018), 317. See also the remarks by Abdel-Razzaq Takriti, “Afterword,” in Guirguis (ed.), The Arab Lefts 1950s-1970s, 277-278. An example of this politically focused approach, in the former book, is Toby Matthiesen’s article dealing with the Arabian Peninsula during the “Global Sixties” and his description of the Palestinians as “the key link between the Gulf region and broader developments in the Middle East during the Global Sixties”: Toby Matthiesen, “Red Arabia: anti-colonialism, the Cold War, and the Long Sixties in the Gulf States,” in Chen, Klimke, Kirasirova, Nolan, Young, and Waley-Cohen (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of the Global Sixties, 98.

- 41. Hirst, Oil and Public Opinion in the Middle East; Takriti, “Afterword,” in Guirguis (ed.), The Arab Lefts 1950s-1970s, 259-282.

- 42. John Chalcraft, “Migration and Popular Protest in the Arabian Peninsula and the Gulf in the 1950s and 1960s,” International Labor and Working-Class History, n°79, 2011, 28-47; Toby Matthiesen, “Migration, Minorities, and Radical Networks: Labour Movements and Opposition Groups in Saudi Arabia, 1950-1975,” International Review of Social History, vol. 59, n°3, 2014, 473-504.

- 43. Robert Vitalis, America’s Kingdom: Mythmaking on the Saudi Oil Frontier (London: Verso, 2009), 149-153; Claudia Ghrawi, “A Tamed Urban Revolution. The 1967 Riots in Saudi Arabia’s Oil Conurbation,” in Fuccaro Nelida (ed.), Violence and the City in the Modern Middle East (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2016), 109-126; Rosie Bsheer, “A Counter-Revolutionary State: Popular Movements and the Making of Saudi Arabia,” Past and Present, vol. 238, n° 1, 2018, 233-277; Mufid al-Zaydi, al-Tayyarat al-fikriyya fi-l-Khalij al-‘arabi, 1937-1971 (Beirut: Markaz Dirasat al-Wahda al-‘Arabiyya, 2020), 62-64; Hirst, Oil and Public Opinion in the Middle East, 31; Mordechai Abir, Saudi Arabia in the Oil Era: Regimes and Elites, Conflict and Collaboration (London: Croom Helm, 1988), 89.

- 44. Interview with Akhbar al-bitrul wal-l-ma‘adin, n°2, 1961, in al-Tariqi, al-A‘mal al-kamila, 120.

- 45. Vitalis, America’s Kingdom, 141-142 and 161-162; Bsheer, “A Counter-Revolutionary State,” 233-277.

- 46. Vitalis, America’s Kingdom, 250; Bsheer, “A Counter-Revolutionary State,” 275-276.

- 47. Ahmad al-Khatib, al-Kuwayt: Min al-Imara ila al-Dawla, Zikriyyat al-‘amal al-watani wa-l-qawmi (Casablanca: al-Markaz al-thaqafi al-‘arabi, 2007), 276-280.

- 48. Matthew Connelly, A Diplomatic Revolution: Algeria’s fight for independence and the origins of the post-cold war era (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003).

- 49. Jeffrey J. Byrne, Mecca of Revolutions: Algeria, Decolonization, and the Third World Order (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

- 50. Dietrich, Oil Revolution.

- 51. Mark T. Berger, “After the Third World? History, destiny, and the fate of Third Worldism,” Third World Quaterly, vol. 25, n°1, 2004, 9-39; Massimiliano Trentin and Matteo Gerlini, “Introduction,” in Trentin M. and Gerlin M. (eds.), The Middle East and the Cold War: Between Security and Development (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012), 1-10.

- 52. Interview of ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi with al-Râ’id al-‘arabi, n°2, 1960, 13-14, in al-Tariqi, al-A‘mal al-kamila, 110-116 ; al-Muharrir, 22 et 23/09/1964.

- 53. Nicolas Sarkis, “Le rôle du pétrole dans le développement et la coopération économiques des pays du Moyen-Orient,” in Pétrole et Développement économique au Moyen-Orient (Paris: Mouton, 1968), 1-15.

- 54. Garavini, The Rise and Fall of the OPEC, 229-230.

- 55. Muhammad al-Rumayhi, al-Naft wa-l-‘alaqat al-dawliya: wajihat nazar ‘arabiyya [Oil and International Relations: An Arab View] (Kuwait: al-Majlis al-watani li-l-thaqafa wa-l-funun, 1982), 165-167; Willard R. Johnson, “Africans and Arabs: Collaboration without co-operation, change without challenge,” International Journal, vol. 35, n°4, 1980, 766-793; Willard R. Johnson, “The Role of the Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa,” The Journal of Modern African Studies, vol. 21, n°4, 1983, 625-644.

- 56. Enzo Traverso, Left-wing Melancholia: Marxism, History, and Memory (Columbia: Columbia University Press, 2017).

Abir Mordechai, Saudi Arabia in the Oil Era: Regimes and Elites, Conflict and Collaboration (London: Croom Helm, 1988).

Bahlul Hasan, “Muhadathat al-bitrul fi Tahran: al-Sharikat al-bitruliya tardikhu li-shurut Munazzamat al-Duwal al-Musaddira li-l-bitrul” [Oil Negotiations in Tehran: Oil Companies yielded to OPEC’s conditions], El-Moudjahid, n°548, 21/02/1971, 12-13.

Mark T. Berger, “After the Third World? History, destiny, and the fate of Third Worldism,” Third World Quaterly, vol. 25, n°1, 2004, 9-39.

Blas Javier and Farchy Jack, The World for Sale: Money, Power and the Traders Who Barter the Earth’s Resources (London: Penguin Books, 2021).

Bini Elisabetta, Garavini Giuliano and Romero Federico (eds.), Oil Shock: The 1973 Crisis and Its Economic Legacy (London: I.B. Tauris, 2016).

Boué Juan Carlos, “The Road not Taken: Frank Hendryx and the proposal to restructure petroleum concession in the Middle East after the Venezuelan pattern,” in Claes Dag Harald and Garavini Giuliano (eds.), Handbook of OPEC and the Global Energy Order (London: Routledge, 2020), 266-277.

Bsheer Rosie, “A Counter-Revolutionary State: Popular Movements and the Making of Saudi Arabia,” Past and Present, vol. 238, n° 1, 2018, 233-277.

Burdett Anita (ed.), OPEC: Origins and Strategy (London: Archives Editions, 2004).

Byrne Jeffrey J., Mecca of Revolutions: Algeria, Decolonization, and the Third World Order (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

Christiansen Samantha and Scarlett Zachary A. (eds.), The Third World in the Global 1960s (New York: Berghahn Books, 2013).

Chalcraft John, “Migration and Popular Protest in the Arabian Peninsula and the Gulf in the 1950s and 1960s,” International Labor and Working-Class History, n°79, 2011, 28-47.

Citino Nathan J., “International Oilmen, the Middle East, and the Remaking of American Liberalism, 1945-1953,” The Business History Review, vol. 84, n° 2, 2010, 227-251.

Connelly Matthew, A Diplomatic Revolution: Algeria’s fight for independence and the origins of the post-cold war era (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003).

Dietrich Christopher R. W., Oil Revolution: Anticolonial Elites, Sovereign Rights, and the Economic Culture of Decolonization (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

Duguid Stephen, “A Biographical Approach to the Study of Social Change in the Middle East: Abdullah Tariki as a New Man,” International Journal of Middle East Studies, vol. 1, n°3, 1970, 195-220.

Ferguson Niall, “Crisis, What Crisis? The 1970s and the Shock of the Global,” in Ferguson Niall, Maier Charles S., Manela Erez and Sargent Daniel (eds.), The Shock of the Global: The 1970s in Perspective (Cambridge Mass.: Belknap Press, 2011), 1-21.

Fuccaro Nelida, “Oilmen, Petroleum Arabism and OPEC: New political and public cultures of oil in the Arab world, 1959-1964,” in Claes Dag Harald and Garavini Giuliano (eds.), Handbook of OPEC and the Global Energy Order (London: Routledge, 2020), 15-30.

Garavini Giuliano, After Empires: European Integration, Decolonization and the Challenge from the Global South (1957-1986) (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

Garavani Giuliano, The Rise and Fall of OPEC in the Twentieth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).

Ghrawi Claudia, “A Tamed Urban Revolution. The 1967 Riots in Saudi Arabia’s Oil Conurbation,” in Fuccaro Nelida (ed.), Violence and the City in the Modern Middle East (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2016), 109-126.

Graf Rüdiger, Oil and Sovereignty: Petro-Knowledge and Energy Policy in the United States and Western Europe in the 1970s (New York: Berghahn, New York, 2018).

Guirguis Laure (ed.), The Arab Lefts 1950s-1970s: Transnational Entanglements and Shifting Legacies (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020).

Hanieh Adam, Money, Markets and Monarchies: The Gulf Cooperation Council and the Political Economy of the Contemporary Middle East (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018).

Hirst David, Oil and Public Opinion in the Middle East (London: Faber and Faber Ltd, 1966).

Johnson Willard R., “Africans and Arabs: Collaboration without co-operation, change without challenge,” International Journal, vol. 35, n°4, 1980, 766-793

Johnson Willard R., “The Role of the Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa,” The Journal of Modern African Studies, vol. 21, n°4, 1983, 625-644.

al-Khatib Ahmad, al-Kuwayt: Min al-Imara ila al-Dawla, Zikriyyat al-‘amal al-watani wa-l-qawmi (Casablanca: al-Markaz al-thaqafi al-‘arabi, 2007).

Mabro Robert, “The International Oil Price Regime: Origins, Rationale, and Assessment,” Journal of Energy Literature, vol. 11, n°1, 2005, 3-20.

Madureira Nuno L., “Squabbling Sisters: Multinational Companies and Middle East Oil Prices,” Business History Review, vol. 91, n°4, 2017, 681-706.

Matthiesen Toby, “Migration, Minorities, and Radical Networks: Labour Movements and Opposition Groups in Saudi Arabia, 1950-1975,” International Review of Social History, vol. 59, n°3, 2014, 473-504.

Mitchell Timothy, Carbon Democracy: Political Power in the Age of Oil (London: Verso Books, 2011).

Nolan Mary, “Where was economy in the global sixties?” in Jian Chen, Klimke Martin, Kirasirova Masha, Nolan Mary, Young Marilyn, and Waley-Cohen Joanna (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of the Global Sixties: Between Protest and Nation Building (New York: Routledge, 2018), 315-327.

Oliveiro Vernie, “The United States, Multinational Enterprises, and the Politics of Globalization,” in Ferguson Niall, Maier Charles S., Manela Erez and Sargent Daniel (eds.), The Shock of the Global: The 1970s in Perspective (Cambridge Mass.: Belknap Press, 2011), 143-155.

OPEC, Public Relations Department, Radical Changes in the International Oil Industry During the Past Decade, IVth Arab Petroleum Congress organized by the Secretariat General of the League of Arab States (Geneva: OPEC, 1963).

al-Rumayhi Muhammad, al-Naft wa-l-‘alaqat al-dawliya: wajihat nazar ‘arabiyya [Oil and International Relations: An Arab View] (Kuwait: al-Majlis al-watani li-l-thaqafa wa-l-funun, 1982), 165-167.

Sargent Daniel J., “The United States and Globalization in the 1970s,” in Ferguson Niall, Maier Charles S., Manela Erez and Sargent Daniel (eds.), The Shock of the Global: The 1970s in Perspective (Cambridge Mass.: Belknap Press, 2011), 49-64.

Sarkis Nicolas, Pétrole et Développement économique au Moyen-Orient (Paris: Mouton, 1968).

Sarkis Nicolas, “Musharakat al-Duwal al-‘Arabiyya fi Imtiyazat al-bitrul” [Participation of Arab Countries in Oil Concessions], al-Tali‘a, n°401, 1972, 8-9.

Sarkis Nicolas, Le pétrole à l’heure arabe: Entretiens avec Eric Laurent (Paris: Stock, 1975).

al-Sayf Muhammad ‘Abdallah, ‘Abdallah al-Tariqi: Sukhur al-naft wa-rimal al-siyasa (Beirut: Riad El-Rayyes Books, 2007).

Takriti Abdel-Razzaq, “Afterword,” in Guirguis Laure (ed.), The Arab Lefts 1950s-1970s: Transnational Entanglements and Shifting Legacies (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020), 277-278.

al-Tariqi ‘Abdallah, “Ayna zahabat ‘uquluna?” [Where have our minds gone?], al-Tali‘a, n°317, 6/03/1971, 8-11.

al-Tariqi ‘Abdallah, al-A‘mal al-kamila, edited by Walid Khadduri (Beirut: Markaz Dirasat al-Wahda al-‘Arabiyya, 2005).

Traverso Enzo, Left-wing Melancholia: Marxism, History, and Memory (Columbia: Columbia University Press, 2017).

Trentin Massimiliano and Gerlini Matteo, “Introduction,” in Trentin M. and Gerlin M. (eds.), The Middle East and the Cold War: Between Security and Development (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012), 1-10.

Vitalis Robert, America’s Kingdom: Mythmaking on the Saudi Oil Frontier (London: Verso, 2009).

al-Zaydi Mufid, al-Tayyarat al-fikriyya fi-l-Khalij al-‘arabi, 1937-1971 (Beirut: Markaz Dirasat al-Wahda al-‘Arabiyya, 2020).