Documentary sources on hydrocarbon exploitation in Franco’s Spain: The ENCASO archives

Universidad de Alcalá, Spain

The Empresa Nacional Calvo Sotelo de Combustibles Líquidos y Lubricantes (ENCASO) was a company created in 1942 within Spain’s National Institute of Industry (INI) by Minister Juan Antonio Suanzes, in an effort to control the country’s strategic energy sector. Established after the Spanish Civil War, it was created to produce hydrocarbons and energy-related products during the first phase of the Franco regime. Synthetic fuels and energy production became national political priorities during the postwar period due to Spain’s policies of economic and industrial autarchy. This paper focuses on the rediscovery of the ENCASO archives, which are conserved at the General Archive of the Administration (AGA), and have only recently begun to be examined. They have received very little attention from researchers, despite being central to studying the social, political, economic, and industrial production of hydrocarbons in Spain during the twentieth Century. The ENCASO archive has not yet been consulted mostly due to a lack of archival processing; until very recently, it was kept in the original office filing boxes, with generic descriptions of its content, and major conservation problems. It has now been appraised—its documentary series have been identified and assessed—and classified, thereby allowing for future access for the purpose of historical research.

Origin of ENCASO

La Empresa Nacional Calvo Sotelo de Combustibles Líquidos y Lubricantes, s.a. (ENCASO) was created as a public limited company by notarial deed on 24 November 1942, in the context of the post-civil war period and the uncertainties of the Second World War1. The Franco government needed to revive the economy and rebuild the country after the armed conflict. However, it was isolated on the international scene, with this loss of confidence translating into an autarchic approach that lasted until 1959. ENCASO was created to cope with this challenge, in order to prospect for and exploit the mineral resources and hydrocarbons that the country could not import due to its international isolationism.

Energy production and the manufacture of synthetic fuels became national monopolies, and were controlled by another institution of the Franco regime, the Instituto Nacional de Industria (INI). The INI was created to provide institutional support for developing industrial activity in Spain; it operated between 1941 and 1980, and its functions were ultimately assumed by the Sociedad Española de Participaciones Industriales (SEPI) in 1995. The idea of making energy production an industrial priority and a national defence strategy—casting aside private initiative—arose during the civil war, and was carried out by the Minister Juan Antonio Suanzes, the director of the INI.

The company was launched through the National Plan for the Manufacture of Liquid Fuels and Lubricants and Related Industries,” which was approved on 26 May 1944. The initial infrastructure was created, and major contracts were awarded to build large complexes in Cartagena, Puertollano, Ebro, and As Pontes de García Rodríguez. A research centre was also created in Madrid to study shale oil distillation and fertilizer manufacturing. Facilities for manufacturing liquid fuels, lubricants, and nitrogen fertilizers from resources extracted from national mines were put into operation in the 1950s. Self-sufficiency in raw materials drove growth in industrial production until the 1960s. The Cartagena branch split in 1958, creating its own group under the name of Refinería de Petróleos de Escombreras s.a. (REPESA), leaving distribution and sales to the company operating the concession, which at that time was the Compañía Arrendataria de Petroleos, s.a. (CAMPSA).

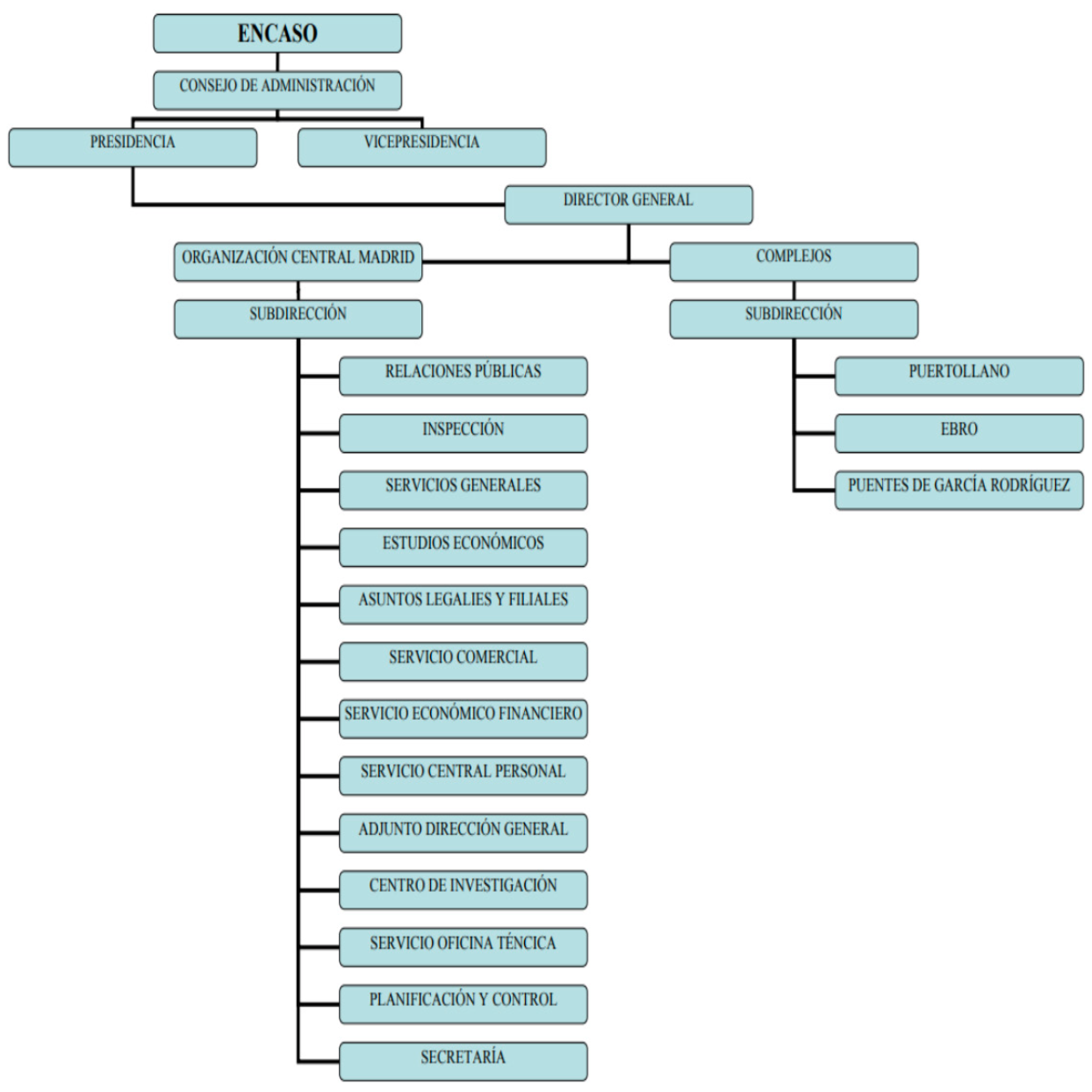

Up through the 1970s, ENCASO’s structure was defined by three main production complexes specializing in mineral extraction and the manufacture of derived products, along with the Madrid Research Centre:

- The Ebro Complex (Zaragoza and Teruel) was built by Grupo Minero de Andorra, an important actor in lignite mining, and included a thermal power plant in Escatrón for coal-based energy production;

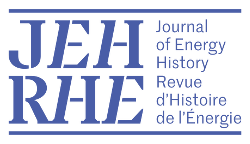

- The As Pontes de García Rodríguez Complex (La Coruña) had an open-pit coal mine, now closed. Once extracted and gasified, the lignite was used to obtain ammonia and calcium ammonium nitrate to produce fertilizers and to produce energy in its thermal power plant;

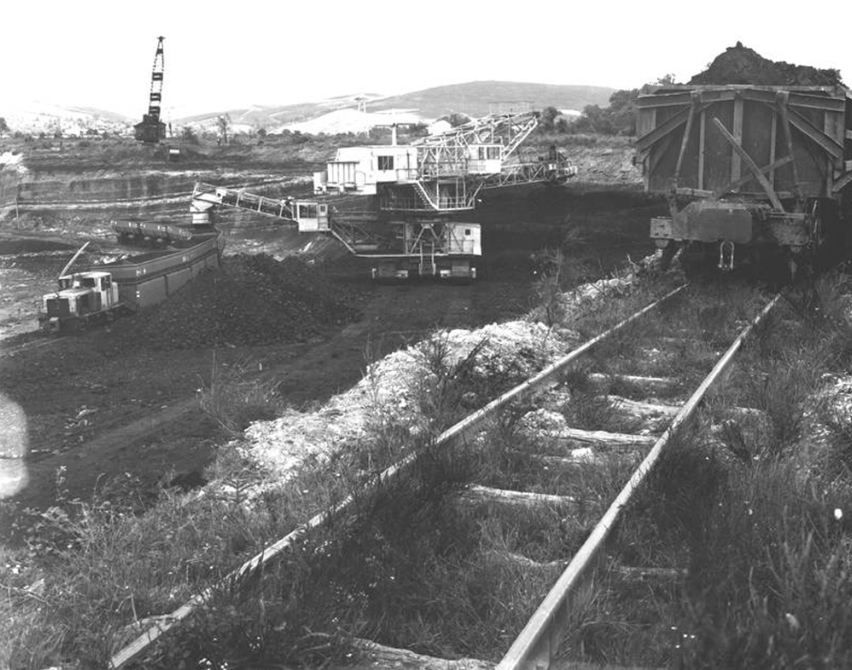

- The Puertollano Industrial Complex (Ciudad Real) was built to exploit bituminous shale, from which nitrogen and hydrogen were obtained to manufacture ammonia and nitrogen fertilizers. This industrial centre was the main supplier of lubricants in Spain. It was reconverted in 1965 by order of the government, once autarchic policies came to an end. It expanded so widely that the area’s shale mines were closed in order to focus on refining oil and its derivatives. Important engineering works were carried out, and a 264-kilometer pipeline was built from the complex to the port of Malaga to transport the oil. These engineering works made the Puertollano Complex one of the Spain’s most important and modern industrial centres, a benchmark for its petrochemical industry. The Puertollano Petrochemical Complex specialized in the production of petrochemical products, gasoline, kerosene, and diesel, as well as the prestigious CS lubricants and to a lesser extent fertilizers. The group diversified into other related activities by integrating the subsidiaries Alcudia, Calatrava, Paular, Montoro, Oxycros, Plásticos Vanguardia, and Bioquímica Española, which specialized in manufacturing polyethylene, plastics, polypropylene, oxide, ethylene glycol, styrene, propylene oxide, and vinyl chloride. These subsidiaries and the refinery itself collaborated with large and prestigious national and international companies for the manufacture and distribution of their products;

- The Research Centre in Madrid was in charge of improving production processes and products, studying and solving the main problems that arose during the production and commercial processes.

The 1970s marked the end of ENCASO as an independent group. The final years of the Franco regime were characterised by the 1973 economic crisis and by a more liberal economy, with privatizations and the concentration of strategic industries, especially those related to energy. Two events marked the end of ENCASO as an independent group during this decade. The first was the merger of Empresa Nacional de Electricidad (ENDESA), also funded in the postwar years by the INI with Hidrogalicia; this created one of the most important electricity production groups in Spain, with the subsequent acquisition of numerous mining operations, and the creation of thermal power plants. This group acquired the Puentes Complexes by García Rodríguez and Ebro. The second was the merger on 28 November 1974 of ENCASO—specifically the Puertollano Petrochemical Complex—with Refinería de Petróleos de Escombreras SA (REPESA) and Empresa Nacional de Petróleos de Tarragona (ENTASA), creating the National Company of Petroleo group (ENPETRO). The entire petrochemical industry and related activities were thus merged into one large group, with the state owning 70% and the private sector 30%. This was the beginning of the liberalization process, which would continue with Spain’s accession to the European Union in 1986, as well as the creation of REPSOL in 1987 by the Spanish Hydrocarbons Institute. This later led to the complete privatization of the sector, and its division between the oil companies CAMPSA, CEPSA, REPSOL, and PETRONOR.

Organisation of ENCASO

The organisation of ENCASO mirrored the typical structure of any state company of the time. ENCASO’s document production was closely connected to its organisational structure. Article 15 of ENCASO’s by-laws indicated that its governance and administration would be entrusted to two bodies: the General Assembly and the Board of Directors. The General Assembly consisted of the shareholders, and was organized through ordinary and special meetings called by the Board of Directors. Ordinary meetings were held during the first six months of each fiscal year to review the company’s management, and to approve, where appropriate, the previous fiscal year’s accounts and balances. Special meetings could be called by the Board of Directors, or upon the request of partners representing at least one tenth of the capital. The General Assembly redistributed profits, and was in control of appointing and removing directors. Other functions included decisions involving issuing bonds; increasing or decreasing capital; transforming, merging or dissolving the Company; and modifying its by-laws. The minutes, which detailed what occurred during the meetings and what resolutions were adopted, were signed by the President and the Secretary. Shareholders could request reports or information on the matters discussed during meetings, and some agreements were also recorded in the national Company Register.

The Board of Directors administered the company and represented it. It consisted of a minimum of 8 and a maximum of 16 directors, appointed by the General Assembly. The Board elected a President, Vice President, and Secretary, who may or may not be a director. The powers of the Board were, among others, to represent the Company in agreements and contracts; to appoint and remove the directors, managers, or administrators of the company’s activities and facilities, as well as to determine their duties; to appoint staff and determine their duties; to organize, direct, and oversee the Company’s progress and to propose internal regulations; to conduct an overview of the company’s operations based on its by-laws; to agree to credit or loan operations; to establish budgets, authorize expenses, and appoint proxies and representatives of the Company; to present to the General Assembly the accounts, balance sheets, and explanatory reports of the Board’s management; to schedule ordinary and special meetings; and to execute all agreements.

Back to topThe archival history of the documentary collection

The General Archive of the Administration (AGA) is the records management institution of the Spanish state, created by decree in the 1970s. The original collections were those of the Franco government’s administration, along with the collections of the Francoist institutions that were liquidated during the reorganisation that followed the arrival of democracy. As an intermediate archive, the AGA’s functions included identifying and appraising the documentary collections that entered its deposits. ENCASO was a company of Francoist origin that ceased to depend on the INI, passing into the hands of private capital in 1974. Funds from the Franco era were also sent to the AGA.

The ENCASO archive was delivered to the AGA in the 1980s by its successor company REPSOL. Although the state of conservation for the documentation is generally good, part of the archive was in a highly advanced state of deterioration. The documents were organised according to the company’s internal records retention policy; they came in the original office boxes, each with a label containing a brief description of the contents. ENCASO had its own filing system and record retention policy, which regulated the lifecycle for the company’s documents, as well as rules for appraisal and descriptions. According to these standards, ENCASO’s documents had four main subdivisions:

- Office Archive: documents used very frequently by the job holder.

- Workgroup Archive: documents used by a group on a frequent basis, at least once a month.

- Central Archive: deposit site for documentation produced by the central offices, and subject to retention requirements; documents could be accessed frequently, but were not essential to have on site in the offices.

- External archives: documentation created and used outside of the central offices, and sent to headquarters when no longer used, in accordance with record retention requirements under law or internal guidelines.

ENCASO created a system of transfers from the offices to the Central Archive. A record was kept for any documents that were sent, including the following fields in an effort to keep track of the files sent to the Central Archive: subject number, subject, shipment date, service, employee, foreign shipment date, destruction date, and general observations. The Central Archive administrators who received the documents checked that the description was duly completed, paying special attention to the destruction date or the shipment date to the external archive. The archive manager would then file the record by shipment date. The Central Archive also established a process for requesting records: an employee seeking to recover documents in the Central Archive had to fill in a request form with the following fields: subject number, subject, shipment date, service, observations, employee name, and request date. Once this was done, the archive administrator located the record, noted the name of the employee’s service and the request date on the envelope, and then sent it to the requester, ensuring to always be aware of what records were outside the the Central Archive, and periodically requesting their return. When the documents were returned, request forms were also archived for future statistics.

There is no evidence of an historical archive in the company itself. The only intervention on the archive was carried out when the company moved headquarters, at which time it analysed the state of its documentation, and submitted a report to the AGA that has survived. In such situations, the documentation of institutions usually suffers irreparable losses; from what is indicated in the report, this was probably also the case for the ENCASO documentary collections. The report indicates that before the move, the company had never carried out an organised document destruction effort, which meant that there was a huge volume; individual offices were subsequently tasked with conducting the effort themselves. Despite the existence of reference guidelines, the hasty and unsupervised destruction presumably led to the loss of documentation that should have been preserved. Furthermore, many documents that have survived were slated for destruction under the guidelines issued as part of the company’s move, showing the challenges of carrying out a proper document destruction process without specific archival expertise. The guidelines stated the following for each type of document:

- Correspondence relating to agreements or legal affairs should be kept for 2 years after completion of the relevant process.

- Studies, reports, and internal correspondence should be kept while relevant, and for an additional 5 years if of great importance.

- Other documents relating to projects, or plans connected to works, facilities, or products should be kept only while relevant.

- Publications and unofficial newspapers should be kept for 5 years, only for interesting articles.

- Statistics should be kept for 5 years after being used and summarized.

- Statistical summaries should be kept permanently.

- Price rates and circulars should be kept for 5 years once their validity has expired.

- Official periodicals should be kept for 2 years from the date of publication.

The rules of the Commercial Code (Real Decreto de 22 de agosto de 1885 por el que se publica el Código de Comercio) also applied:

- The company’s official books: 15 years from the date of the last entry.

- Correspondence, business papers, sales documentation affecting legal transactions: 15 years.

- Minutes from Board of Directors meetings and company agreements: while the legal subject they represent continues to exist.

- Contracts and deeds: 15 years after taking effect.

Documents whose retention status was uncertain were sent to the service heads for each department in order to relieve the burden on the central office.

There was no subsequent archival treatment for the documentation in the Central Archive. The archive was stored at the AGA for almost thirty years with no intervention whatsoever, until in 2017 when I was appointed by the AGA to proceed with appraisal and to grant access. Because of its historical interest and deteriorating state, I undertook several archival efforts. The Identification and Appraisal Service of the Department of References performed three tasks:

- Identification of divisions and documentary series (According to ENCASO’s organisational structure)

- Appraisal of each documentary series to determine what parts should be destroyed or preserved.

- Reorganisation of the documentation to separate those in a poor state of preservation from those in a good state of preservation.

Appraisal and Identification of Documentary Series

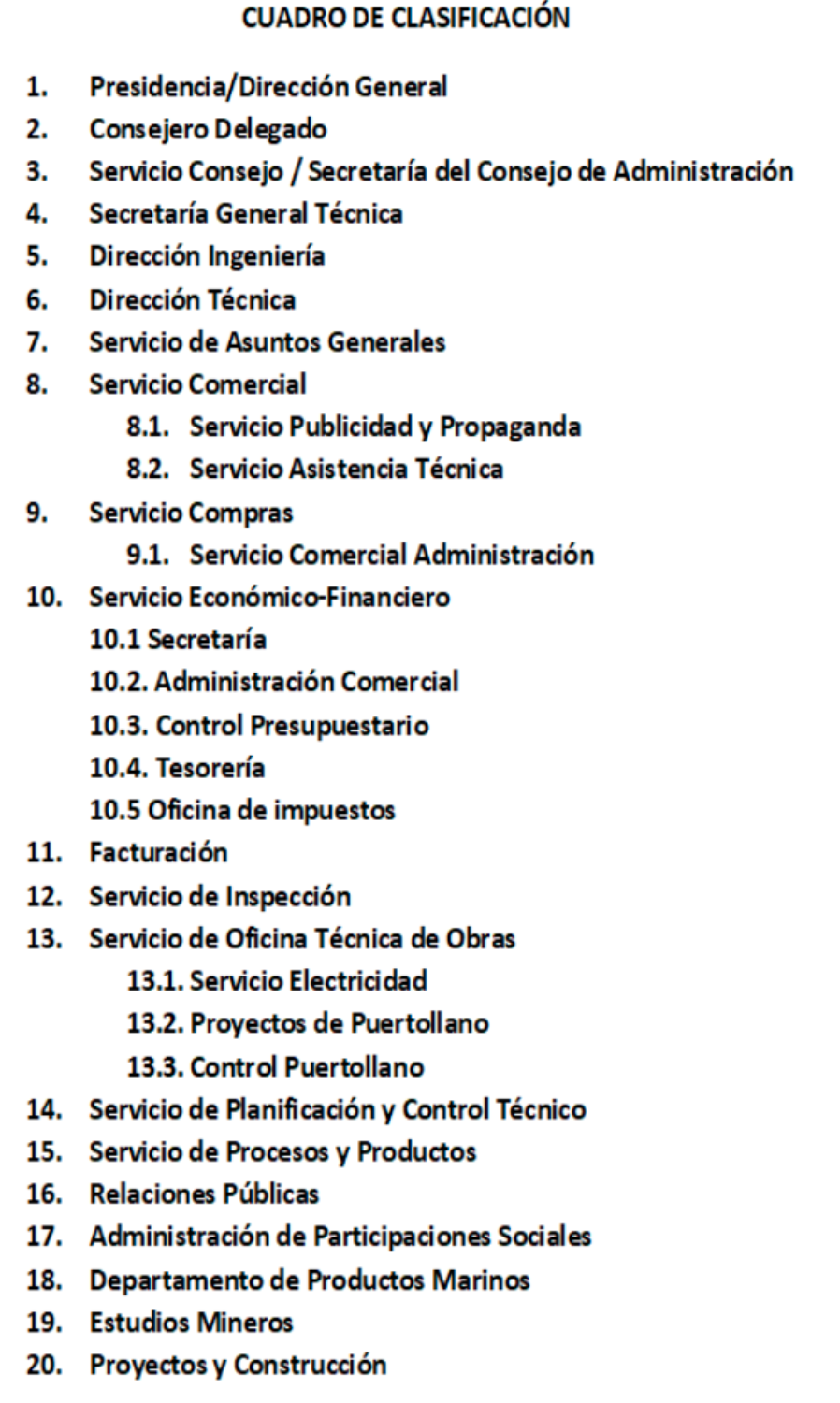

As we saw in the previous section, the archive did not identify or evaluate the documentary series, but only proceeded with the destruction of records while they were still in the offices, based on the criteria established by the aforementioned guidelines. For this reason, the Identification and Appraisal Service of the Department of References at the AGA completed the study of the documentary collections, with a view to establishing adequate identification based on the information attached to the boxes. It also carried out an assessment on access to the collections, determining which documentary series should be permanently preserved and opened to the public, and which should be destroyed. The assessment was submitted to the Higher Qualifying Commission for Administrative Documents, and is currently awaiting a response. Over 2,600 boxes were analysed, with each document contained in the units being identified and classified according to the organisational chart (see fig.1) and functional structure of ENCASO. As the various documentary series were identified, the documents selected for permanent preservation were evaluated and separated from those slated for destruction; some documents were purged by nature, due to their poor state of conservation following degradation from fungi or dirt. The identification and assessment sheets were prepared according to the model of the Higher Qualifying Commission for Administrative Documents. The identification and appraisal process allowed us to generate a classification table for the various types of documents in the archive:

A list of suggested items for conservation and destruction was also created.

Documentary series identified for possible conservation

- Presidency / General Directorate: correspondence (1974-1975); budget reports (1973-1974).

- Secretary of the Board of Directors: proposals presented to the Board and the Permanent Commission (1947-1974); projects presented to the Board and the Permanent Commission (1951-1974); Board Meeting agendas (1972-1973); Permanent Commission Meeting agendas (1972-1973); Directors’ Committee Meeting agendas (1972-1973); agreements of the Board of Directors (1957-1971); Board and Permanent Commission Meeting minutes (1969-1974); Extraordinary General Assembly Meeting minutes (1953-1974); outgoing correspondence from the Board of Directors (1952-1973); correspondence exchanged with the INI (1968-1973); correspondence exchanged with various councillors (1968-1973); incoming correspondence (1967-1973); Board agreements relating to the As Pontes y Escatrón Complex (no date).

- Chief Executive Officer: reports and correspondence between various departments and for the Board (1963-1974).

- Control Puertollano: studies (1967-1971), reports (1969-1973), payment proposals (1969-1973).

- General Directorate of Engineering: supply contracts (1972-1975); correspondence (1972-1975); reports (1971-1974); reports (1970-1971); inventory of planning archive (1975-1977); summaries of activities (1971-1974).

- Technical Direction: minutes (1972-1973); conferences (S.F.); employment contracts (1972-1973); supply contracts (1974); correspondence (1972-1973); information files (1959-1973); reports (1972-1973); economic reports (1970-1974); technical reports (1970-1980); reports (1972); economic offers (1973-1974); business agendas (1973-1974); proposal to the Board (1973); technical projects (1969); internal claims (1972-1973).

- Administration of company shares: correspondence with various companies (Alcudia, Paular, Bioquímica Española, Calatrava, Electro, Termoeléctrica del Ebro, Elaboración de Plásticos Españoles, Plásticos Vanguardia, Montoro, Cydeplas, Macaya Lubricantes, Oxycros, as well as with the INI) (1953-1972).

- Department of Marine Products: correspondence with various services (1969-1975).

- Mining Studies: contracts (1950-1970); correspondence (1967-1971); mining reports (1962-1973).

- Puertollano Project: photographs of the construction project (1972-1973).

- Advertising and Propaganda: correspondence about participation in various events and championships (1967-1973); correspondence with representations and delegations (1969-1973).

- Public Relations: correspondence of visits, inaugurations, anniversaries (1962-1972); photographs (1960-1970).

- General Technical Secretariat: Board of Director meeting minutes (1942-1954); project control (1974); correspondence (1957-1960); reports (1943-1973); activity summary reports (1945-1972); national manufacturing plans (no date); proposals to the Permanent Commission (1945-1958); projects (1946-1972).

- General Affairs Service: meeting minutes (1969-1970); economic agreements (1970); conferences (1944-1971); contracts (1952-1974); correspondence (1948-1973); deeds of purchase and sale (1942-1958); personnel files (1963-1970); reports (1959-1972); economic reports (1963-1970); technical reports (1941-1972); instruction manuals (1970); economic and social development plans (1965-1966); correspondence (1966-1972); requests (S.F.), economic-administrative decisions (1965); supplies of inventoried materials (1966-1967).

- Technical Assistance Service: correspondence (1966-1973); travel accounts (1968-1972); reimbursements (1971-1972); reports (1971-1973).

- Commercial Service: correspondence (1962-1973); memories (1966); reports (1965-1972); planes (1971); works projects (1961); activity summary reports (1969); expenditure records (1968).

- Commercial-Administration Service: correspondence (1960-1974); budgets (1968-1972); insurance policy transactions (1959-1975); reports (1970-1972).

- Budget Control Service: correspondence (1966-1972); technical-economic reports (1964-1970); technical plans (1971-1972); financing files (1968-1974); contract liquidations (1972).

- Purchasing Service: expense records (1964-1973); activity reports (1971).

- Economic-Financial Service/Treasury: correspondence (1965-1974).

- Economic-Financial Service/Accounting: correspondence (1963-1973), technical-economic reports (1969); reports (1972-1973).

- Economic-Financial Service/Secretariat: meeting minutes (1970-1971); correspondence (1953-1973); financial contracts (1964); service contracts (1963-1965); reports (1957-1966); technical-economic reports (1963); record books (1969-1973).

- Economic-Financial Service/Tax Office: correspondence (1962-1974); tax records (1953-1973).

- Electricity Service: meeting minutes (1971-1974); inspection certificates (1953-1973); service contracts (1967-1973); technical-economic reports (1957-1975); technical-economic projects (1965-1971); thermal energy settlements (1963-1973); thermal compensation statements (1967-1970); electric tributes (1973-1974).

- Inspection Service: Permanent Commission meeting minutes (1942-1963); travel accounts (1972-1973); daily cash and bank bulletin (1972-1973); inspection reports (1947-1973); balance sheets (1964-1970); studies (1972-1974).

- Works Technical Office Service: meeting minutes (1969-1973); contracts (1969-1972); work contracts (1951-1973), service contracts (1956-1970); correspondence (1964-1975); information files (1962-1969); records of works (1958-1972); acquisition records of inventories (1971-1973); records of award proposals (1970-1971); supply files; meeting reports (1967-1971); economic reports (1967); technical reports (1959-1972); annual reports (1968-1969); economic offers (1968-1973); start-up parts (1970-1971); budgets for works and facilities (1970); reports of incidents of facilities (1970-1971); technical plans (1952-1972); construction projects (1967-1974); correspondence register (1967-1971); facilities repairs (1970-1971).

- Planning and Technical Control Service: correspondence (1964-1970); reports (1965-1967).

- Processes and Products Service: correspondence (1968-1971); reports (1963-1973); production statistics (1957-1964), manufacturing plans (1970-1971).

Documentary series for possible destruction

- Control of Puertollano: offers not selected for hiring (1969-1972).

- Billing: invoices (1972-1973); quality certificates for facilities and appliances (1965-1970); material shipment notifications (1968); production parts (1973); delivery notes for monopolized products (1972-1973); dispatch notices (1971-1973); credit notes (1972-1973); billing orders (1972-1973); packaging movements (1973); invoice summaries (1972-1973).

- Technical Office/Projects and Construction: orders for the different facilities and projects (1965-1974), timesheets (1972), copies of isometric plans (1968-1971), spare parts (1968-1972), invoices (1967-1972), quality certificates (1968-1974), expenditure certifications (1971-1973), material shipment notifications (1968-1970), production parts (1972-1974), production summaries (1973-1974), accounting notification minutes (1973), expenditure distributions (1971), warehouse stock parts (1972-1974), credit notes (1973), billing orders (1970-1973).

- Economic-Financial Service: invoices (1966-1974), timesheets (1972), production summaries (1973), delivery notes (1971-1974), shipment notices (1973-1974), credit notes (1973 -1974), billing orders (1970-1975).

- Commercial Service: orders for the different facilities and projects (1964-1974), invoices (1966-1975), production parts (1972), production summaries (1972), delivery notes for monopolized products (1972-1974), warehouse stock reports (1974), dispatch notices (1971-1974), credit notes (1974), billing orders (1974), container movements (1972-1974), transport settlements (1964-1970), insurance premium payments (1965-1975).

- Engineering Directorate: spare parts (1973), production parts (1970-1975).

- Advertising and Propaganda: invoices (1970-1974).

- Budgetary Control: invoices (1968-1972), quality certifications of facilities and fixtures (1972).

- General Affairs Service: magazine subscription and cancellation records and invoices (1948-1977), files with translation registrations (1956).

- Planning and Technical Control Service: production parts (1970-1971), production summaries (1970-1972).

- General Secretariat/Production Department: production parts (1949-1960).

- Distribution: production parts (1973-1974).

- Processes and Products Service: production summaries (1968-1972).

Sources for Research on the History of Hydrocarbons in Spain

The ENCASO archives are of interest for researchers because they cover various subjects in Spanish contemporary history. The documents are of particular interest because they provide the researcher not only with primary sources generated by the institution in the exercise of its functions, but also with reports and projects summarizing the institution’s overall activity over the years, with assessments of the company itself as well as the sector, the economy, and broader society. These reports were produced on a monthly or annual basis. Some of them were published as monographs, and they were also sent to the INI, so that a copy is now available at the library of the Sociedad Española de Participaciones Industriales, which is extremely important given that many of the reports given to the AGA had suffered irreparable damage.

The ENCASO archive also has a special place within the larger landscape of the historical heritage of Spanish energy complexes due to its photographic and audio-visual archives, and architectural heritage. The ENCASO archive itself holds a photographic collection capturing the construction phases and inauguration of the company’s industrial complexes. Similar material can be found in the archives of the news agency EFE, which was active throughout the Franco regime; in the municipal archives where these facilities were located; and in private documental collections. With regard to audio-visual heritage, it is also important to mention the archives of the Noticiario y Documentales (No-Do), the state company that produced newsreels from 1943 to 1981, which reflected Francoist propaganda and ascribed great importance to state infrastructure, including energy.2

As the industrial heritage of cities is often being repurposed today for a second life by ascribing new uses to facilities, documents relating to industrial architecture are of particular importance. In the case of ENCASO, the architectural historian Felipe Carmona Arriaga wrote a doctoral thesis on the architecture and urban planning generated by ENCASO’s activities3. His research is based on documentation for construction work, meeting minutes, agreements, technical reports, and photographic and audio-visual documents, in an effort to reconstruct the evolution of industrial buildings over time. Arriaga consulted ENCASO’s documentary collection prior to the AGA’s conservation interventions, and his thesis is also interesting from an archival point of view, as he comments on his experience accessing ENCASO’s documentation, highlighting its poor state of conservation.

Another interesting line of research for the history of ENCASO is the relationship between the company and its personnel, although the records of the central personnel service where personnel files would be found are unfortunately not available. It is nevertheless possible to find information on this subject inside other documentary series, making it possible to reconstruct the company’s permanent and contract staff. This reveals, for example, the broad participation of specialized technical personnel from the United States in the construction of facilities, which is striking due to the isolation endured by Spain during the Franco regime. Another interesting discovery in the archives is the workplace practice, during the dictatorship years, of employment recommendations. Evidence of this can be found in ENCASO correspondence, which includes numerous letters to leadership requesting access to a job, showing the extent to which this custom was ingrained in Spanish business culture. Finally, there is also news on personnel management, labour negotiations, retired personnel, and mutual insurance companies, among others, in the minutes and proposals submitted to the Board and the Commission, as well as in correspondence and reports. One example is personal loans for staff to finance the purchase of a home. ENCASO itself built large complexes that included services for workers, as well as affordable housing for which workers could get a loan directly from the company.

All in all, the ENCASO archives provide an important overview of Spain’s society and economy during these years. The archives are now available for consultation for researchers, while efforts to establish the collections continue.

- 1. Paola Massa, Los empresarios de Franco: política y economía en España, 1936-1957 (Barcelona : Crítica, 2003).

- 2. One example is this file on the establishment of the Cartagena refinery can be consulted online: Archivo Historico RTVE, Rafineria de Escombrera (1950), available at <https://www.rtve.es/alacarta/videos/archivo-historico/refineria-escombr…;.

- 3. Felipe Arriaga Carmona, Teoría y práctica del urbanismo y la arquitectura promovidos por las empresas públicas en la España de la autarquía (PhD thesis, Universidad de Castilla La Mancha, 2017).

Arias Fernández Modesto, La etapa del franquismo en Puertollano (1939-1975) (Puertollano: Intuición Grupo Editorial, 2005).

Arriaga Carmona Felipe, Teoría y práctica del urbanismo y la arquitectura promovidos por las empresas públicas en la España de la autarquía (PhD thesis, Universidad de Castilla La Mancha, 2017).

Asenjo Conde Elena, Marta Santarmía Alday, FEFASA, (1940-1972): un gran complejo industrial en Miranda de Ebro: (análisis económico y social de una empresa durante el franquismo) (Miranda de Ebro: Instituto Municipal de la Historia, D.L. 1988).

Cruz Mundet, La gestión de documentos en las organizaciones (Madrid: Ediciones Pirámide, 2006).

Díaz Fernández José Luis, “Los hidrocarburos en España: Cincuenta años de historia”, Economía industrial. Cincuenta años de economía industrial, nº 394, 2014, 103-115.

García García Rafael, “Un paisaje de hormigón. La estructura de FEFASA en Miranda de Ebro de Eduardo Torroja”, in Miguel Ángel Álvarez Areces (coord.), Resiliencia, innovación y sostenibilidad en el Patrimonio Industrial (Gijón : Centro de Iniciativas Culturales y Sociales, 2019).

García Ruiz José Luis (coord.), Políticas Industriales en España: Pasado, Presente y Futuro (Madrid: Paraninfo, 2019).

González Pedraza José Andrés, Los archivos de empresas: qué son y cómo se tratan (Gijon: Trea, 2009).

Martín Aceña Pablo, Francisco Comín Comín, INI: 50 años de industrialización en España (Madrid: Espasa Calpe, 1991).

Massa Paola, Los empresarios de Franco: política y economía en España, 1936-1957 (Barcelona: Crítica, 2003).

Núñez Orjales Marina, Manuel Souto López, “El poblado industrial das Veigas en As Pontes de García Rodríguez (A Coruña) evolución histórica, problemática urbanística y jurídica”, De Re Metallica (Madrid): revista de la Sociedad Española para la Defensa del Patrimonio Geológico y Minero, nº 18, 2012, 43-54.