Commercial strategies to promote domestic gas and electricity consumption, and the role of women (Lisbon, 1891-1970s)

Universidade de Évora- CIDEHUS

anamariacmatos[at]gmail.com

Universidad Nacional de Rosario

die.bussola[at]gmail.com

Research leading to this article was funded by FCT-Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (Portugal’s national research agency) under the project UIDB/00057/2020, and by the Ministry of Science and Innovation of the Government of Spain and FEDER under the project PID2020-112844GB-I00, “Gas in Latin Europe: A Comparative and Global Perspective (1818-1945)”. We would like to express our gratitude to Fatima Mendes and Ivone Maio, from the EDP Foundation Documentation Centre (CDFEDP), for their invaluable assistance, especially given the current pandemic circumstances. We are thankful to two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and to Léonard Laborie, JEHRHE’s managing editor, and the proof-reader.

By the 1870s the gas industry had no competitors for lighting, turning it into a near monopoly. However, by the 1880s the possibility of using electricity for street lighting changed the equation and the threat for gas industry was huge. This new promising competitor caused some people to forecast the end of the gas industry. In this context, in 1891 by the fusion of two gas companies, the Companhia Reunidas de Gás e Electricidade (CRGE) was created to produce and sell gas and electricity to Lisbon and its outskirts. In this paper we analyse the marketing strategies of this company as a particular case in which the introduction of electricity was made in complementarity (and not competition) with the gas industry. The company marketing strategies of these new energies reinforced genre stereotypes of housewives and husbands and their roles in the home. They also developed and consolidated the idea that a modern house should be equipped with gas and electricity appliances. We will show that the promotion of these new appliances was made through press advertisements, warehouses, stands and cooking courses, among others.

Plan of the article

- Introduction

- The CRGE company and its monopoly of the production and distribution of gas and electricity in the city of Lisbon

- “Gas and Electricity for everyone”: Marketing strategies for encouraging home consumption of gas and electricity, up to the late 1930s

- Gas versus electricity consumption in the Post-World War II period

- Strategies for the development of non-competing gas and electricity markets after World War II

- Washing machines and TV sets as symbols of modernity, and the new role of women up to the 1970s

- Conclusion

Introduction

From a 1946 article in the Eva magazine, containing several photos of an American kitchen designed by Jerry Fairbanks, we can perceive housewives’ desire to have a modern kitchen “as if they lived in America”:

When will we have this? (...) How many inventions contributing to the housewife’s wellbeing (...)

Pity us, still working with utensils identical to those from the Middle Ages (save for the vacuum cleaners, the flatirons and the electric stoves which only millionaires can afford) (…)

When will our electricity suppliers decide to provide us with electric power at a price fitting civilized people, who need it not for luxury but for making life easier, instead of issuing charges at every opportunity?1

The sentence above illustrates well how the American household propaganda influenced the way in which in other countries household gas and electricity consumption was looked upon as progress in terms of welfare. Nevertheless, to understand why in 1946 Eva magazine published this article, we have to understand how this symbolic universe that articulates issues of modernity, energy consumption, gender roles and domesticity was constructed.

When studying the use of gas and electric domestic appliances of Lisbon’s households, we consider it essential to analyse the role played by the city’s gas and electricity distribution company in the rise observed in their domestic consumption, through its marketing strategies aimed at promoting “modern energies” and the appliances which would facilitate women’s chores and improve life in the home.

However, an approach to the use of domestic appliances at home must take into account a series of factors, such as the availability of the energies that power those appliances; the supply of running water; the spatial reorganization of the kitchen/bathroom to receive new equipment; a commercial framework to enable their purchase; and the engineers, technicians, and industrialists who ensure the smooth operation of all the preceding elements. This is why Ruth Schwartz Cowan defends that “the concept of technological system becomes important in understanding the processes by which the American home became industrialized”.2

Ruth Schwartz Cowan’s book, which looks at how advances in technology and the use of new forms of energy translate into new ways of organising domestic work, can be considered a classic.3 The links between women and the use of different energy sources within the domestic space have also been analysed in works from other countries. In particular for the case of Barcelona we can highlight Mercedes Arroyo’s book on the gas industry until the 1930s,4 and for France the book by Alain Beltran and Patrice A. Carré, which among other aspects refers to domestic electricity consumption.5 In these two books the commercial strategies followed by the companies to promote domestic consumption of gas and electricity are also addressed. This theme had already been explored in 1987 by Jeanne Boin.6 In the same decade, Jane Busch analyses these strategies for the American case.7

In recent years several works have contributed to these themes. Anne Clendinning focuses on the British gas industry and analyses the role of women as gas workers and energy consumers.8 Also in recent years there has been a growing interest in energy consumers. The article by Yves Bouvier refers to the diversified approaches that can be made to energy consumption, even if the concepts of energy or consumers are not always clear.9

For the Portuguese case, electricity consumption is analysed in the book by Ana Cardoso de Matos et al. between the end of the 19th century and World War II, with Lisbon as the central case.10 Also for Lisbon, Diego Bussola, analyses the participation of Société Financière de Transports et d’Entreprises Industrielles (SOFINA) in Companhia Reunidas de Gás e Electricidade (CRGE) and the regulation of electricity throughout the 20th century.11 Concerning the domestic use of the energies sold by CRGE, one can refer to the book As imagens do gás where an approach is made to the evolution of gas consumption connected to domestic applications in the city of Lisbon and the strategies to encourage consumption until World War II.12 For the later period Diego Bussola addresses the issue of household appliances linked to electricity consumption, focusing on electricity tariffs.13

However, to the present day there has been no study for the Portuguese case on CRGE’s marketing strategies focusing on the place given to women and relating it to the evolution of household consumption of the energies sold by the company. Thus, in this article we seek to: analyse the marketing strategies directed mainly towards women; demonstrate that the strategy of promoting domestic consumption of gas and electricity was not competitive, but complementary, which was reflected in the marketing itself.

Two sets of documents were used for this study. On the one hand, the documentation of the company CRGE that is available at the EDP Foundation Documentation Centre (CDFEDP) - CRGE Collection: Annual Board Report, Management Board Minute Book, Statistical Elements and pictures; and, on the other hand, magazines and newspapers: EVA, O amigo do lar, Crónica feminina, Banquete and Diario de Notícias. On this documentation we performed a quantitative analysis of the production and consumption of gas and electricity, and a qualitative approach oriented towards the analysis of the commercial strategies and use of these energies in the domestic space, which enabled us to address gender issues related to the use of energies.

In the first part we analyse the household consumption of gas and electricity in the city of Lisbon from the creation of the company (1891) until the 1930s. We then discuss CRGE’s marketing strategies to sell gas and electricity to domestic consumers until the 1930s and the stereotypes reinforced by its advertising. Then, we show how the Second World War conditioned and modified domestic consumption of gas and electricity. In the fourth part, we examine the marketing strategies of the CRGE in the post-war period. Finally, we show how the post-war advertising of the CRGE reinforced family stereotypes and adjectivized the domestic use of gas and electricity.

Back to topThe CRGE company and its monopoly of the production and distribution of gas and electricity in the city of Lisbon

The company CRGE was created in 1891, resulting from a merger of the two companies which exploited the production and distribution of gas in the city of Lisbon - the Companhia Lisbonense de Iluminação a Gás, founded in 1846, and the Companhia do Gás de Lisboa, founded in 1887 -, and by the contract established with the Lisbon City Hall, by which it committed to introducing electricity to the city of Lisbon.

From 1891 onwards, then, the distribution of these two kinds of energy was exploited as a monopoly. This fact prevented competition by other players, but also forced CRGE to find different markets for these two energy types, and the marketing policies developed throughout the years always took this into account. In fact, the contract signed by CRGE with the Lisbon City Hall, in 1892, gave it the concession to supply gas for public lighting and to private customers, to introduce electric lighting on the Avenida da Liberdade and, later on, in other areas of the city, and finally to supply electricity to private customers.

On the other hand, the fact that CRGE had an important proportion of foreign capital namely French and Belgian, led foreign stakeholders to intervene in defining the company’s management – especially after 1913, when SOFINA became the owner of a large portion of the capital. Thus, many of the strategies for promoting the consumption of gas and electricity, namely in the home, saw direct or indirect intervention by SOFINA, by the transfer of publicity models.

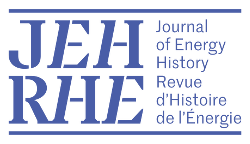

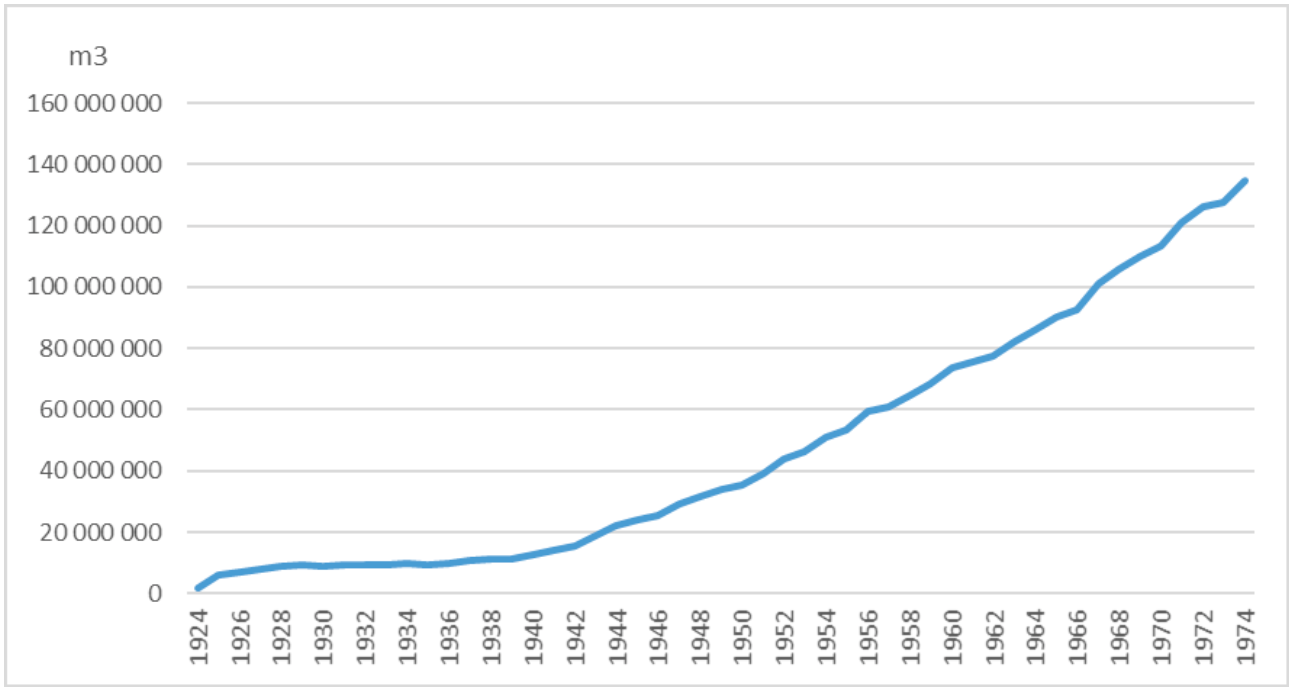

For a more global understanding of the dimension of domestic gas consumption, we have to consider it within the global evolution of gas consumption in Lisbon and relate it to the size of the capital’s population.

From the moment when CRGE started to supply gas to Lisbon and its outskirts, consumption saw a rising trend until the eve of World War I, at which time there was a sharp drop due to the scarcity of the fuel necessary to keep up production.14

At the end of the 19th century, public and private lighting still accounted for a large proportion of total gas consumption, leading CRGE in 1898-1899 to assign to the company Sociedade de Incandescência – Bec Rationel the exclusive rights, in Portugal, to utilize their nozzle which, according to that year’s board report, “so effectively contributed to the development of our consumption”.15 This rise in private consumption had been helped by the spread of kitchen stoves and the installation of new industrial engines, which in that year consumed 477.297m3 of gas.16

A wider utilization of gas-powered engines and stoves was essential to secure gas consumption during daytime, in order to make production profitable, since the use of gas for lighting was mainly reserved for the night-time hours.17 In 1905, due to the increase in gas consumption, both domestic and industrial, CRGE installed a new gasholder, with a 20,000m3 capacity.18

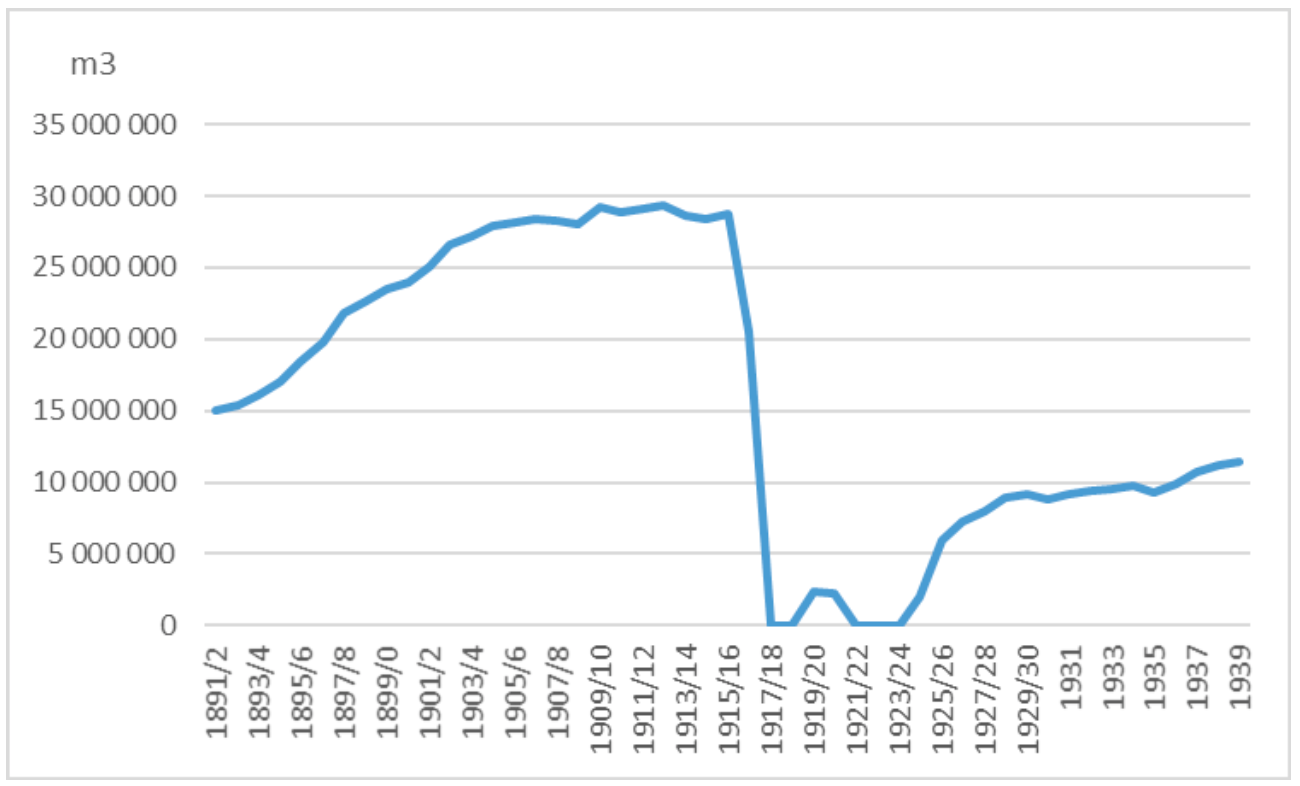

At that time, however, and until the 1930s, gas production was essentially directed to public and private lighting. Per capita consumption remained very low – there was even a reduction in the 1930s (figure 2).

Rising coal prices during World War I made it necessary to raise the price of gas in the city of Lisbon, and to impose restrictions on its consumption, e.g. by reducing commercial opening hours and delaying the time for turning on public lighting lamps19. This resulted in a 28% cut in gas consumption, although there was actually a rise in the number of consumers.20

In the war years, losses from gas supply were so big that in the economic year of 1917/1918 CRGE decided simply to cut it.21 The option to close down the gas plant was only possible because the contract signed with the City Hall allowed for gas lighting to be replaced by electric light, and CRGE exploited both energy distribution networks in Lisbon. Besides, some areas in the city were already being served by electric lighting. When gas production was reinitiated, in 1925, private consumers adhered almost instantly, causing a trend toward higher gas consumption, even though throughout the 1930s the figures stayed below those registered before the war (figure 1).22 Per capita consumption, on the other hand, remained low for almost two decades, and could not climb back even to the figures reached in 1916 (figure 2). Even if we consider that the figures before the interruption were in large part coming from public lighting, this fact still illustrates the low gas consumption levels seen from the end of World War I to the beginning of World War II.

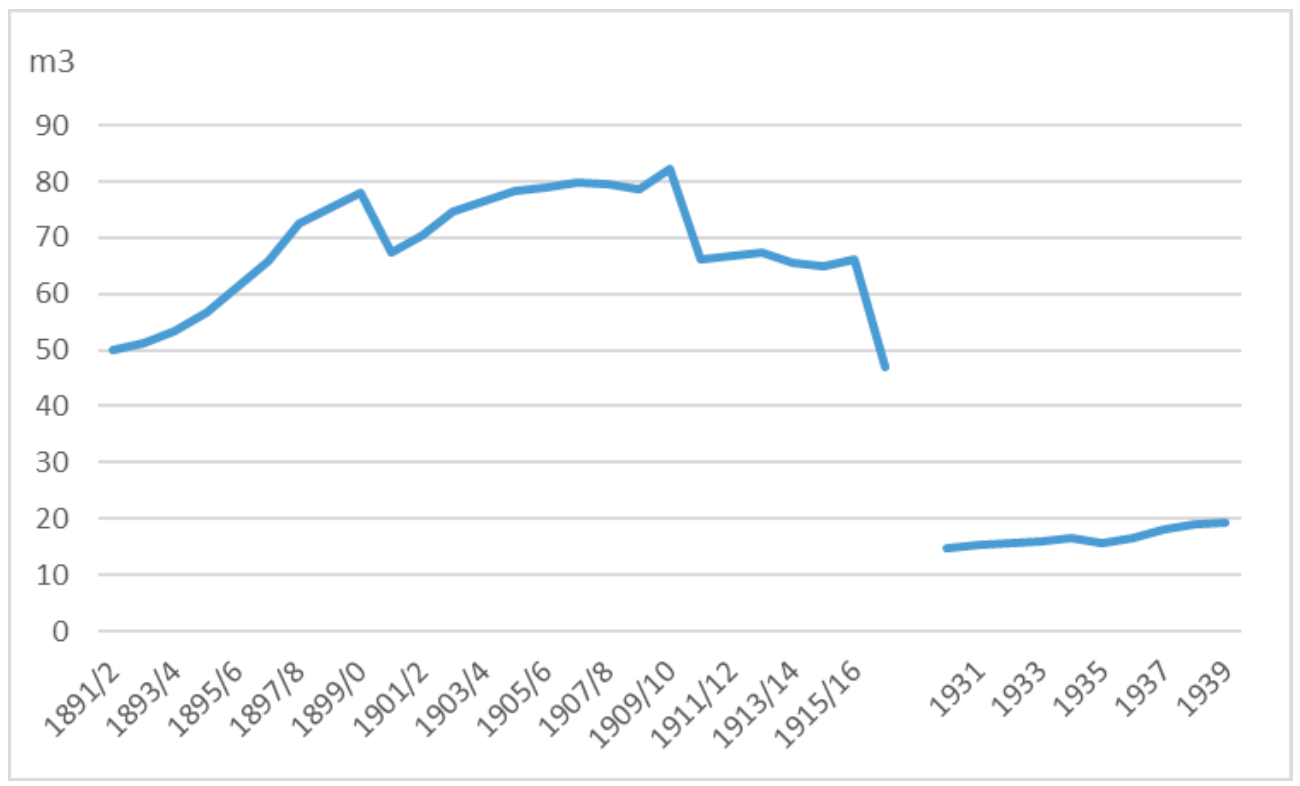

From the moment when the production and distribution of electricity in the city of Lisbon began, its inhabitants showed great interest in this novel form of energy and lighting. Despite the difficulties experienced by the company since the start of World War I, the number of electricity consumers rose - from 1,085 in 1908/1909 to 6,814 in 1916/1917 (figure 3).

Even though data on the number of consumers was available only from 1907 to 1920, the different figures reflect growth both in the quantity consumed and the number of consumers. While in 1917 there were 8,127 consumers accounting for a 6.55 GWh consumption, by 1929 those figures had risen to 77,409 consumers and a 45.48 GWh consumption. Throughout this decade, however, electricity in the home was above all used for lighting. As a matter of fact, due to World War I restrictions electricity replaced gas for home lighting.

In the period between the wars, CRGE went from being essentially a gas producer to an electricity producer. In 1936, the central government decided to allow declining block rates to come into use, with the aim of promoting electricity consumption.23 In January 1937, CRGE started to apply these rates to private consumers who requested them. The first and highest rate (1$89.6 escudos) was charged for lighting; the second (1$20 escudos) for small home appliances; and the third (0$50 escudos) for high-consumption electrical home appliances.24

The number of homes with electricity rose considerably in the 1930s, from 60% in 1935 to 73% in 1939, although consumption was essentially linked to lighting, at an average rate of 200kWh/year.25

Back to top“Gas and Electricity for everyone”: Marketing strategies for encouraging home consumption of gas and electricity, up to the late 1930s

Right from the start, CRGE developed a marketing policy aimed at encouraging the use of gas, by increasing quantity but also by diversifying utilization modes. This strategy was essential to ensure the consumption of gas in the daytime, when its use for lighting was next to zero.

Display to publicise

To encourage the use of gas in stoves and other domestic appliances, and in the industry as well, at the end of the 19th century CRGE opened in its warehouse on Rua da Boavista an exhibition “in order to let everyone know about the numerous and important uses that gas can be put to, letting people see and appreciate the best lighting, heating and ventilation appliances. Burners of the most perfect types, kitchen stoves, bath water heaters, and many other appliances can be seen, all of the greatest usefulness”.26 Other undertakings had already established a showroom to promote the usage of gas, as was the case of the English enterprise William Sugg & Cª, that had established one showroom in Liverpool and, with the aim of attracting consumers, in 1887 organised the Liverpool School of Cookery.27 In Paris also, since the 1870s, the company that explored the gas created a showroom, edited manuals for consumers and from 1892 requested the services of a cook to lead culinary conferences.28

Since most of the city’s inhabitants lacked the resources to purchase this kind of equipment, especially if the whole price had to be paid at once, CRGE decided, as early as 1892, to create “a special service to pay for the appliances in instalments, thereby giving everyone access to them”.29 With the aim of promoting the usage of gas-powered kitchen stoves, too, the company lent these appliances to its clients, even taking care of their maintenance without charge. These marketing policies made it possible to make gas stoves common in Lisbon households. In June 1893, the number of gas stoves functioning in the homes of private customers had risen to 4,970.30

Sales figures for this warehouse exhibition are not known, but the fact is that in 1912 the Board of Directors decided that the service of displaying the gas-powered home appliances was “costly” and that “the usefulness it had some years ago has now become doubtful.”, thus considering it “opportune to supress this complementary service”.31 However, in the 1930s, with the appearance of new gas appliances, this warehouse exhibition reopened to the public with a more appealing presentation of the appliances (figure 4).

The 1920s saw exhibitions linked to the electricity congresses organized in that decade to discuss the main issues surrounding the electrification of the country, which played a very important role in affirming electrotechnical engineering and the electricity industry in Portugal. During the 2nd Electricity Congress, held in the city of Porto from August 31st to September 4th 1924, there was an Exposição de Maquinismos e aplicações da electricidade [Exhibition of Mechanisms and Applications of Electricity], in which were displayed several products for domestic use such as dust suction devices; machines for making ice at home; mechanical kneading machines; electrical irons for clothes; coffee machines, heaters, ventilators; electric stoves, curling tong iron heaters, cigarette lighters and telephones. 32

As currently practised in other countries33, in 1930 was held the Exposição da Luz e da Electricidade Aplicada ao Lar [Exhibition on Light and Electricity Applied to the Home]. It opened on the 22nd of November and was open to the public for 15 days. Its goals were: to show people from trade and industry the effectiveness of light as an element in advertising, by presenting adverts and illuminated billboards, and to tell the general public about the advantages of using electricity at home.34 This exhibition brought together, side by side, the stands of electricity producers and distributors, those of companies which made electrical installations, and those of electrical home appliance retailers, clearly demonstrating the way these three sectors were connected and interdependent. While selling more electrical home appliances was essential to increase electricity consumption levels, and thus to make this business profitable, the converse was equally true. On the CRGE stand, several panels presented diagrams showing electricity consumption beside illuminated billboards and adverts.35

As we mentioned, one of this exhibition’s goals was to promote the new usage of electricity among merchants and general public. Thus the stand of Electro Reclamo Lda, for instance, showed advertisements lighted by electrical power. The various exhibitions organized throughout the 1930s, in which CRGE participated, were important to spread the new utilization modes of electricity, including the domestic ones, although these were often presented in the background.

CRGE’s advertising strategies

By the end of the 19th century, printed advertising had already taken a meaningful role, both as a way of making known the products each company offered and as a form of incentive to consumption. As the Almanach da Agencia Primitiva de Anúncios [Almanac of the Primitive Agency of Advertisements] put it, in 1873, “Nowadays it cannot be denied that advertising is a necessity of society’s economic life, being indispensable to the branches of trade, arts, and industry. An advertisement will propagate, diffuse, enlighten, describe, and allow everyone to cater to their needs, and as a consequence it enables the products relevant to the economy to become well-known”.36

Seeing clearly how important advertising could be in encouraging gas consumption, CRGE regularly posted adverts in several newspapers. As Anne Clendinning points out, gas managers directed their campaigns to female consumers, and doing so “helped to feminise the market for domestic technology by underscoring the point that (…) women were responsible for domestic labour, and, therefore, should be trusted with making important consumer choices for the home”.37

Pursuing the goal of promoting domestic use of gas in the 1890s, CRGE published a brochure called “O GAZ”38 in which, through the use of drawings of gas appliances and colloquial language, the various advantages of using gas were praised. This brochure maintained that by using gas stoves “The fire is always ready, kitchen utensils are always clean, and the servants have no excuse for any lack of cleanliness in the kitchen”. To the question “Is gas cooking expensive?”, the brochure replied “It is not. It is more economical than any other” 39, and went on to suggest that its readers visit CRGE’s exhibition on its Rua da Boavista warehouse, where they could observe how the various devices worked while the company’s employees explained their functioning. As mentioned above, to encourage the consumption of gas in the kitchen, the company supplied gas stoves, at no cost, to all its customers. The brochure also expounded the advantages of several domestic appliances powered by gas, such as a small “toillete” stove, made for heating water for tea and other drinks; coffee roasters; bathwater heaters; flat irons; washing machines; devices for heating dishes; heaters; and ventilators. In the opening decades of the 20th century, nevertheless, the use of these devices continued to be very rare.

The marketing initiatives by CRGE, begun in the 1930s, contributed to generalize the diverse uses of gas40, which remained limited to those social groups with a better financial situation.41 Those campaigns suffered a clear influence from contemporary practices in France, where the pioneering advertising campaigns on electricity had been initiated in 1928 by the Compagnie parisienne de distribution d’électricité (CPDE). They were later transferred to CRGE through SOFINA. In fact, since 1928 the French company created an Agenda de l’Électricité, a very well-illustrated publication that gave lots of advices, and the first number of it sold 60,000 copies.42

The company’s advertising services, supported by French know-how43, implemented a series of actions44: sale on credit of all gas and electricity-powered appliances in cooperation with retailers; a more systematic use of advertising through billboards, illuminated adverts, printed ads, films, radio talks45, shop windows in its sale outlets; the offer of appliances through contests; consumption bonuses or discount coupons for gas on the purchase of appliances; and cooking courses.46 As Jane Busch suggests “advertising campaigns introduced the ranges to the public at large and translated technology into desirable consumer values” as well as “the social status of owning the most modern appliance”,47 whether it was the use of gas in the kitchen or the use of electricity that was sought to promote.

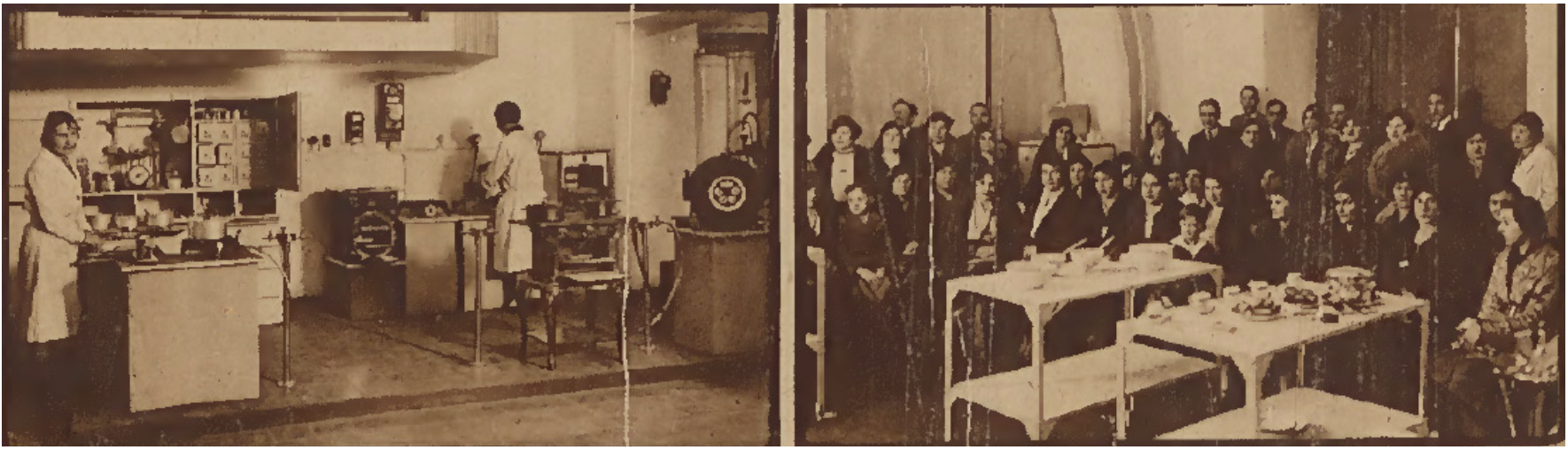

The cooking courses,48 starting in 1932, were part of a strategy for fuel substitution in the kitchen, where up to that point coal and wood had been the main fuels used, replaced during the World War II by gas. The advertisements for these courses sought to draw in upper-class housewives by saying that “Thanks to our Cooking Courses, ladies will be able to cook with gas in an economical, safe and clean way”, and offering housewives a course for their maids on “Careful handling and economical cooking processes with gas”, upon whose completion they would earn a “certificate”, attesting to the maid’s ability to safely and economically utilize the new energy and technology.49 This example lays out very clearly the differences in tasks and social status among the women in the household.

On March 28th, 1925, the newspaper Diário de Notícias advertised Eva, a new magazine dedicated to women, saying that “among us, the purely feminine interests have not been properly considered: we don’t have a newspaper for the Woman”, adding that in this magazine “our readers will find the thousand secrets of those little details which complete and enhance the education of the household companion”.50 The magazine’s first issue came out on April 25th of that year and quickly sold out. The issues that followed met with equal success.51 In the beginning, Eva was directed by a woman, although its editor was a man.

Well aware of the technical improvements and new level of comfort which the use of gas and electricity could offer women at home, notably in the kitchen, at the end of 1932 the magazine Eva set up a salon for cooking courses, which would see a great development from March 1933 onwards. This strategy was part of a new concept of women-oriented services, with the magazine stressing: “It will not merely be a secure and authoritative guide in the matters of elegance, home decoration, etc.; in this way, Eva’s Practical Courses aim to train and perfect housewives, in a modern and elegant ambiance, providing all technical requisites such as sewing, tailoring, hats, etc., all the way to cooking”.52

CRGE took part in this initiative, and the magazine mentioned that “the project, decoration, and equipment of the kitchen” of the salon where the courses were given belonged to the company.53 The innovation represented by giving cooking courses to the women charged with household chores, pioneered by CRGE (November 1932)54 and also developed by the best-selling magazine among housewives (March 1933), was a way of spreading the possibilities of gas, leading housewives to replace traditional fuels with kitchen gas, namely in the stove and in the oven.

Besides collaborating with Eva, CRGE also began to publish its own magazine – O amigo do lar. Edição mensal dos Serviços de Propaganda das Companhias Reunidas Gaz e Electricidade [The Household Friend. Monthly Magazine of CRGE’s Advertising Services]. Its first issue, in December 1932, made clear that its purpose was “to establish between this company and its clients a closer bond of relationship”, and that the publication would be “the tribune from which we will tell our clients about current progress in these two fields of prodigious activity – gas and electricity.”55 This magazine displayed the latest uses of gas and electricity in the home, with the goal of winning over new consumers to these energies. Thus, it was directed at a feminine audience from Lisbon’s urban haute bourgeoisie, the one which could really afford to acquire these novelties. As we can see from the pictures, these courses were attended by ladies of Portuguese high society and their servants (figure 5).

By 1936, the group of appliances linked to the kitchen (ovens and stoves) accounted for almost 70% of domestic consumption, while water heating made up the remaining 30% (since home heating was negligible, at only 0.2%).56

In the pages of O amigo do lar, CRGE played out its strategy of publicizing the use of the energies it sold – gas and electricity – indirectly, through the explanation of how the appliances which used those energies worked. In most cases, texts were limited to a few short notes, accompanied by pictures – expounding the advantages of this or that appliance. In those informative notes, care was taken to show that using those energies posed no dangers or hazards, using slogans such as “cooking with gas, in an economical, safe and tidy manner”.57

Some of these texts resort to fictional stories representing domestic everyday life scenes. In “O mundo não se fez para tôlos”58 [The world was not made for the foolish], for instance, we read a fictional dialogue between husband and wife, with the former showing the latter how much would have been saved if they had adhered to the new tariff scheme. The woman is represented as someone who does not care for the information received from the company, and so does not relay it to her husband, who just got to know about it at a café, “in a chat with his friends”. Male ascendance in terms of technical knowledge is represented by the fact that the husband gives his wife a lesson, while she appears as a fragile person, afraid of the unknown. The husband´s dominance in the home is also demonstrated by his having to request the new tariff scheme, since the service is subscribed by the “head of the family”. This aspect of the situation is laid out in a text in which the husband, holding power and authority, explains to his wife, inattentive and fearful, CRGE’s tariffs for using electricity.59

This kind of advertisement is rich in information and tries to approach the reader using rational explanations. Its target reader is the well-off housewife, who is projected as being rational in the management of her household. For instance, an article on refrigerators includes two pictures with the housewife using them and says: “Maybe she is inclined not to give this subject the attention it deserves. But, after a little reflection, she will surely change her mind.” (figure 6).60

Publishing this magazine was part of a strategy by CRGE, influenced by SOFINA, aimed at increasing domestic consumption of electricity, so as to compensate for the break in industrial consumption brought on by the 1929 crisis. The fundamental goal at that time was to make consumers start using electricity for other purposes, not just for lighting, such as home radios, for instance.61 Some of these ideas and strategies had been presented in the Union Internationale des Producteurs et Distributieurs d’Energie Électrique (UNIPEDE) congresses, where in 1932 it was stated that the use of radio broadcasting had made the private consumers raise their electric consumption by 30% in Strasburg and by 24% in a town in Tuscany.62

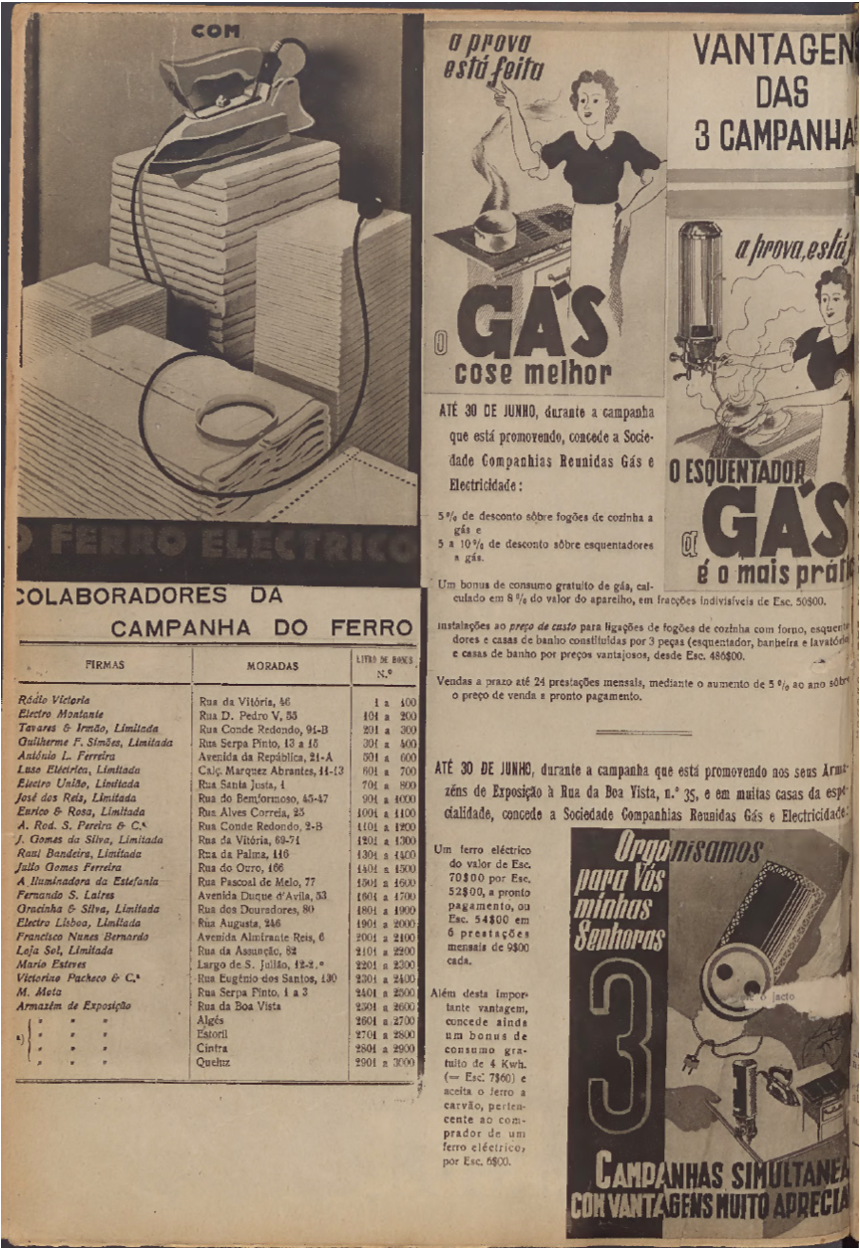

The head of marketing services at SOFINA, Michel Deutsch, took part in the 1934 congress – in the Comité V, Applications, Propagande – which dealt with issues concerning instalment sales. This committee stressed the fact that electricity distributors should guarantee the quality of the electric home appliances they sold to the public. In the 1936 UNIPEDE congress, Michel Deutsch added that they should also sell these appliances, not excluding those with low energy debit, as a strategy to give the consumer the habit of using electricity in other ways, inside the home. He added that electric utilities should organize special campaigns, on a seasonal basis, promoting the intensive sale of certain appliances,63 e.g. the Campanha do Frio [Cold Campaign] in the summer, when refrigerators would be sold at lower prices and in instalments, or the Campanha do Ferro Eléctrico [Flat Iron Campaign], with irons for sale at discounted prices, in instalments.64

CRGE incorporated all these ideas into its marketing strategies from the 1930s on, in its promotion of both gas and electricity.65 Actually, the adverts ended up helping shape the social stereotypes of the day: the husband as the “homo economicus” and his wife as a delicate, feminine and stay-at-home figure, a spouse who ensures the good harmony of the household.66

Back to topGas versus electricity consumption in the Post-World War II period

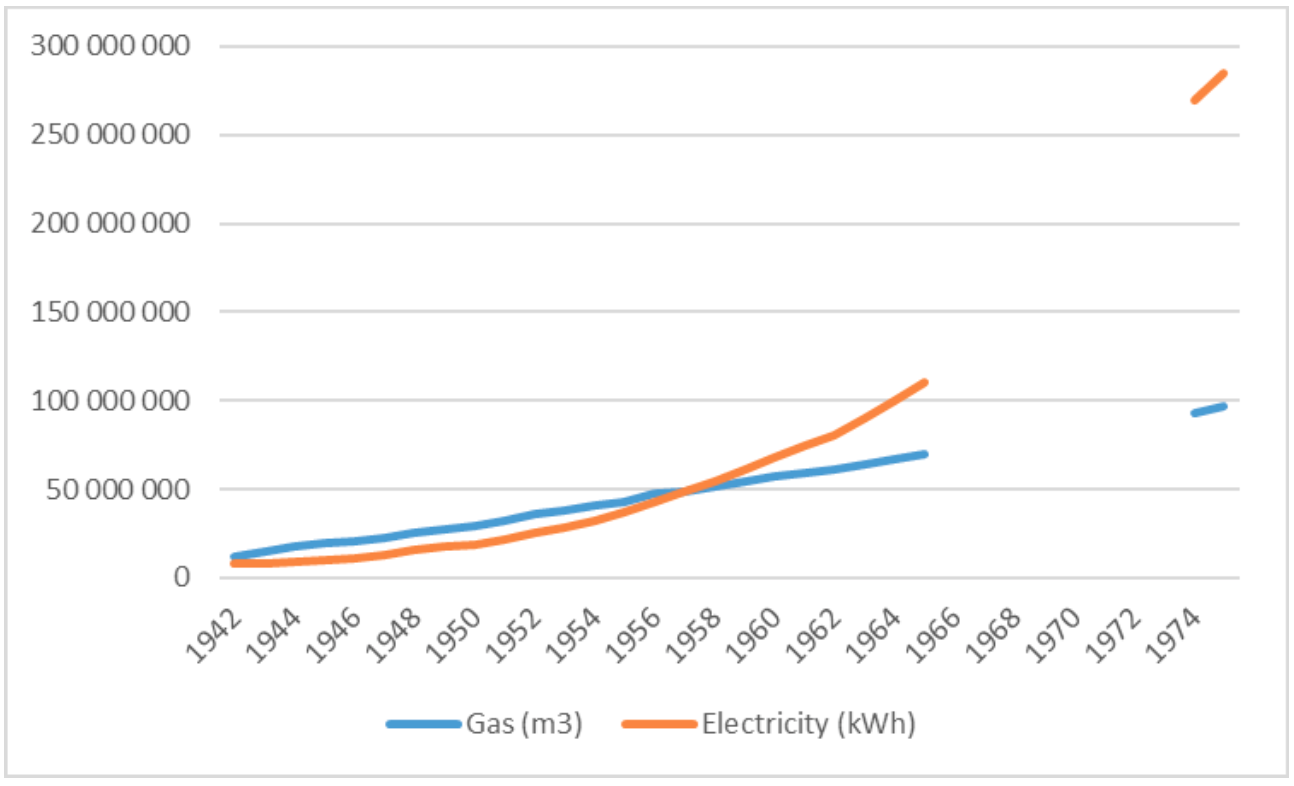

During the war period, gas consumption figures rose exponentially. In the war’s first phase (1939-42), that rise was due to the lack of alternative fuels for home use, such as firewood, hard coal, oil, or vegetal charcoal, which led to gas becoming almost their natural substitute for heating and cooking. In the second phase of the war, starting in April 1942, the lack of mineral charcoal and other energy sources led the government to impose restrictions on electricity consumption. At that stage, gas became its replacement, benefiting from the end of declining block rates and those restrictions on electricity consumption. In this context, CRGE alerted to the fact that the only cheap and available fuel would be gas, making its growing consumption easily predictable: “Currently, only one kind of fuel can be obtained in unlimited amounts, and at the same price it had before the war: gas. We should therefore expect its consumption to rise significantly”.67

These predictions were confirmed in 1943: there was in fact, starting in 1942, a steep rise in gas consumption, a trend which would hold throughout the period we are considering (figure 7).

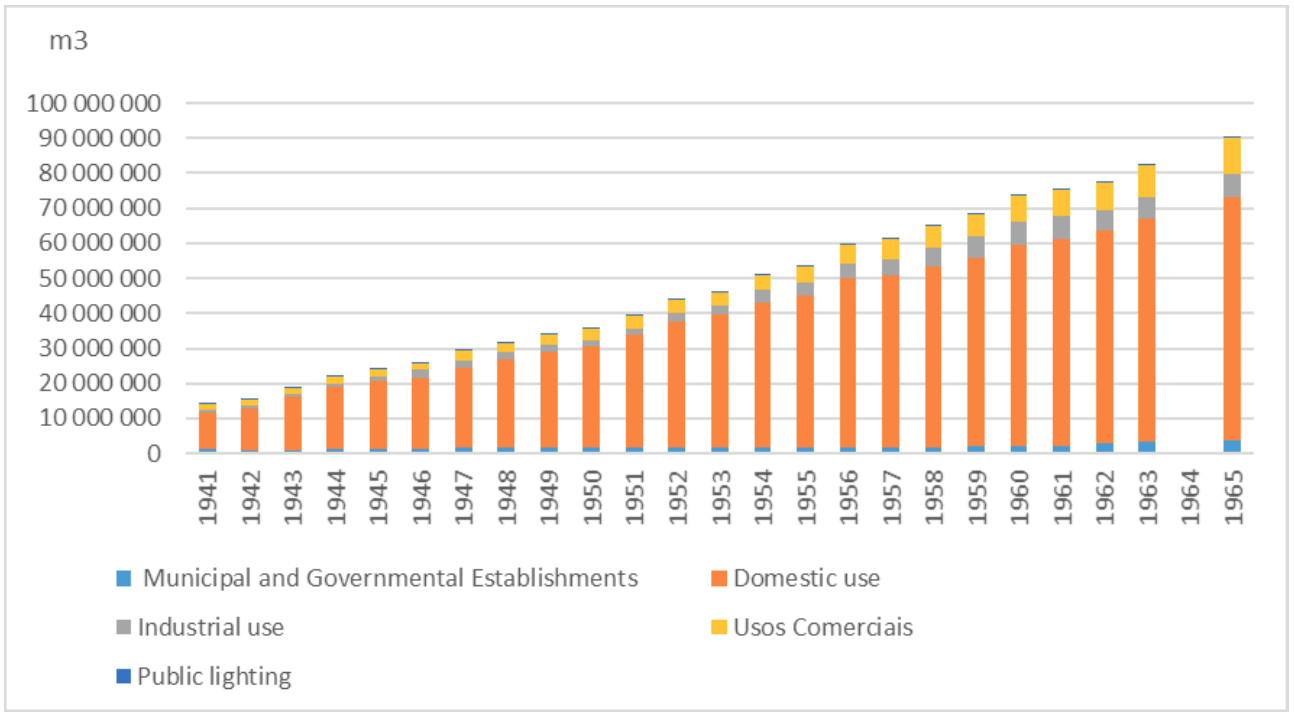

The rise in gas consumption had a considerable contribution from domestic use – and in this process the increase in consumer numbers was more relevant than the rise in per capita consumption. In 1943, for instance, the 27% increase in domestic consumption was partly due to a significant rise in new consumers (12.1%). These figures prove that those who had gas installed probably used it for most of their household activities. Average home consumption rose by 20% every year, from 1941 to 1944, and gas became the only solution used, in Lisbon, for some domestic purposes: cooking and water heating.68 Per capita gas consumption remained very low for many years, however, and only in the 1950s did it reach more significant levels.

The picture of specific gas uses, from 1941 onwards, shows that in that period domestic consumption was the most important, all other types being marginal. The growth in gas utilization until 1965 is directly linked to the rise in domestic consumption (figure 8).

The rationing of electricity consumption during World War II lasted until October 1947. In its report of that year, CRGE considered this to be very detrimental to the company, since it had altered the previous trend to increase domestic electricity consumption and created a habit of reducing electric lighting and suppressing the use of appliances, “which will be felt for a very long time”.69

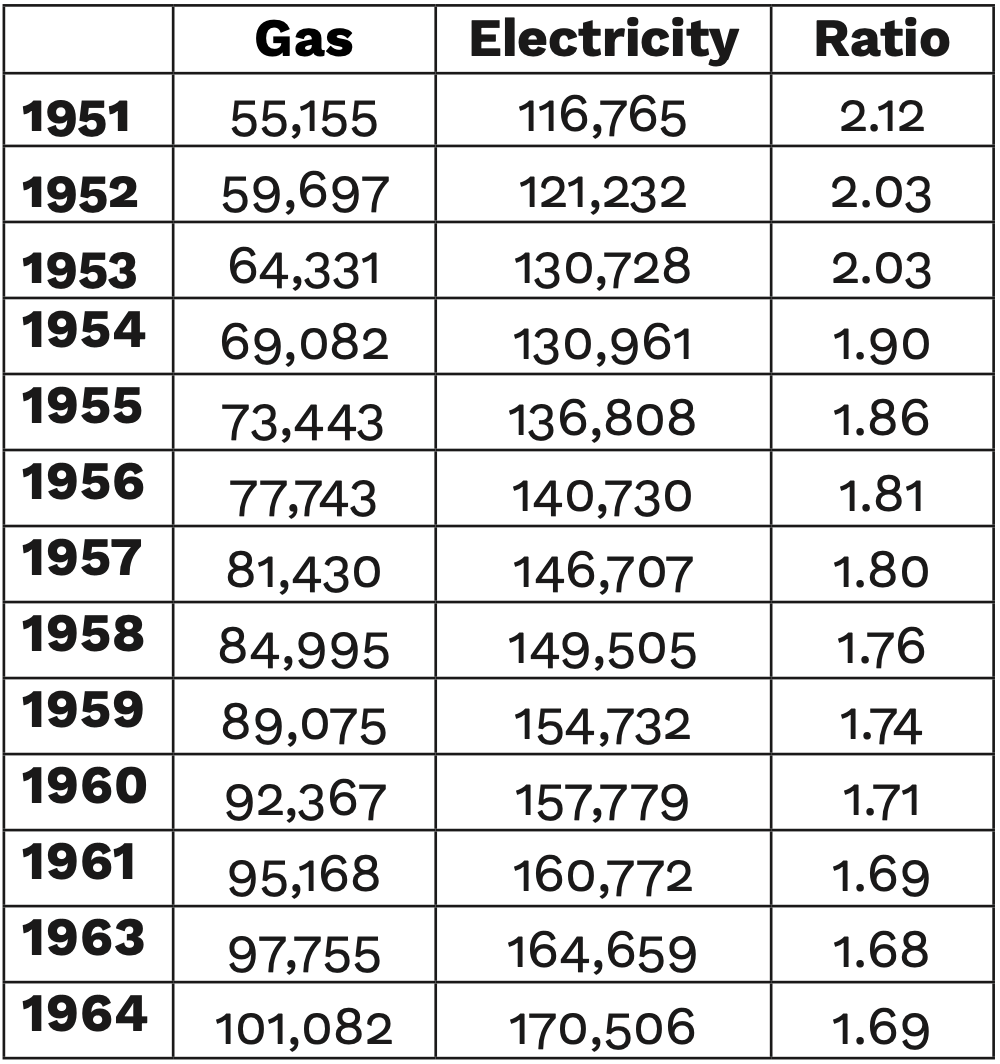

In 1951, the government decided to reintroduce declining block rates as part of its policy to make cheap electricity available, enabling consumers to electrify their homes. These rates promoted the use of electricity by lowering the average price in inverse proportion to the level of consumption and caused electricity consumption in the home to grow at an average annual rate of 11.67% from 1947 to 1975.70

Starting in the 1950s, even as electricity gained importance in the home, gas managed to keep its position due to the fact that the same company exploited both energies and so sought to find non-competing markets. Nevertheless, from the 1950s on, the gas business began to lose relevance among the various activities of CRGE (figure 9): in 1974, the revenue from gas sales was less than half of what it had been in 1955.71 This decrease was helped by the emergence of Empresa Gazcidla [Gazcidla Company], a supplier of bottled gas for domestic use.

Only in the 1960s did the use of gas for commercial and industrial purposes assume greater importance, and CRGE’s campaigns in the 50s and 60s were essentially directed toward industrial uses and big commercial establishments.

Back to topStrategies for the development of non-competing gas and electricity markets after World War II

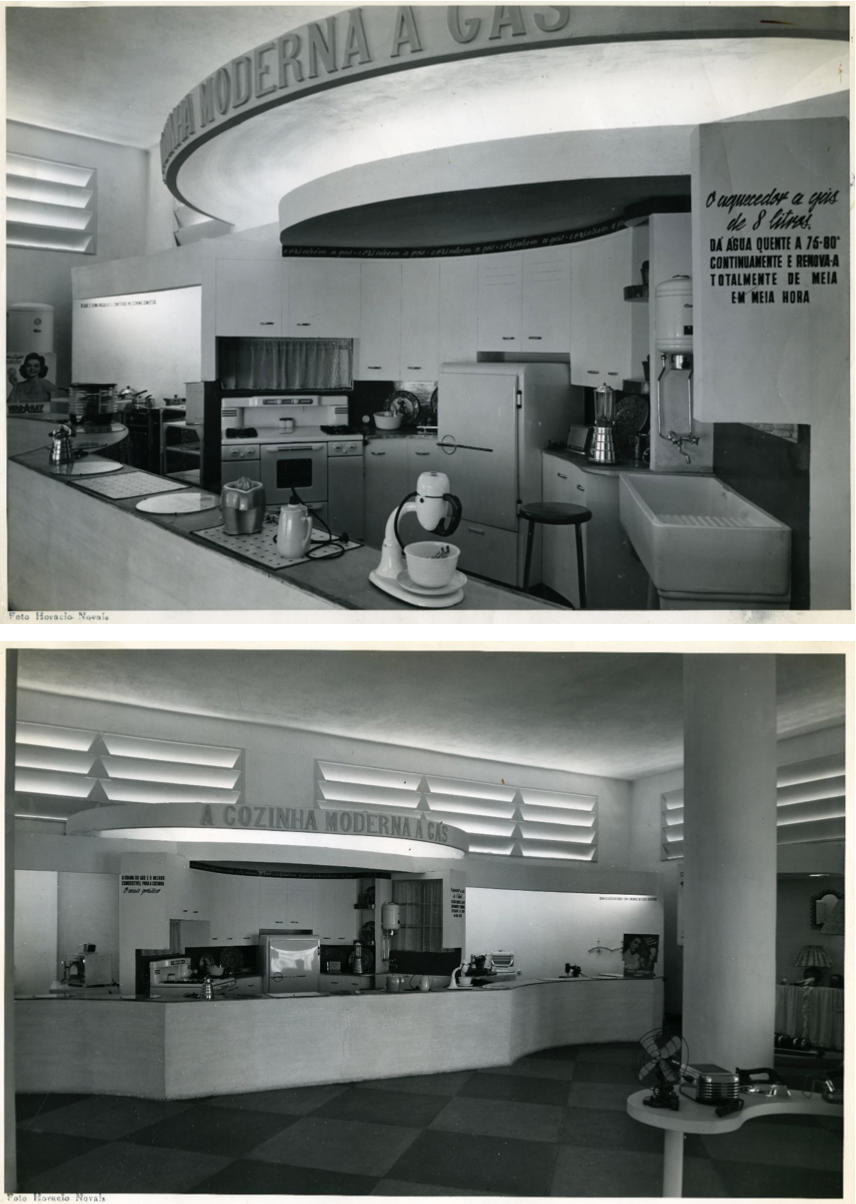

CRGE’s advertising strategy underwent changes in the post-World War II period. The publication of the magazine O amigo do lar was ended, and there was a push for promoting domestic consumption through a more widespread use of gas- and electricity-powered appliances. Although exhibitions and shop-window contests had been produced before, it was at this time that exhibitions gained added importance. Still under restrictions to electricity consumption, CRGE in 1947 set up a stand at Feira Popular de Lisboa [Lisbon Fair], which was then a major leisure and amusement space for Lisbon’s bourgeois families. In that stand were displayed different divisions of a residence with their respective electrical home appliances: living room (vacuum cleaner and floor polisher), small table (flatiron, fan, toaster, etc.), bathroom (shaver, radiator). The central spot belonged to the kitchen, fully equipped, under the slogan “A cozinha moderna a gás” [The modern gas-powered kitchen] (figure 11).

©Centro de Documentação da Fundação EDP

The central position of gas in this stand bore witness to CRGE’s adaptation to wartime conditionings, promoting gas as a symbol of modernization while avoiding any reference to electricity. Since restrictions on electricity consumption were still in place, electrical appliances were relegated to a secondary position.

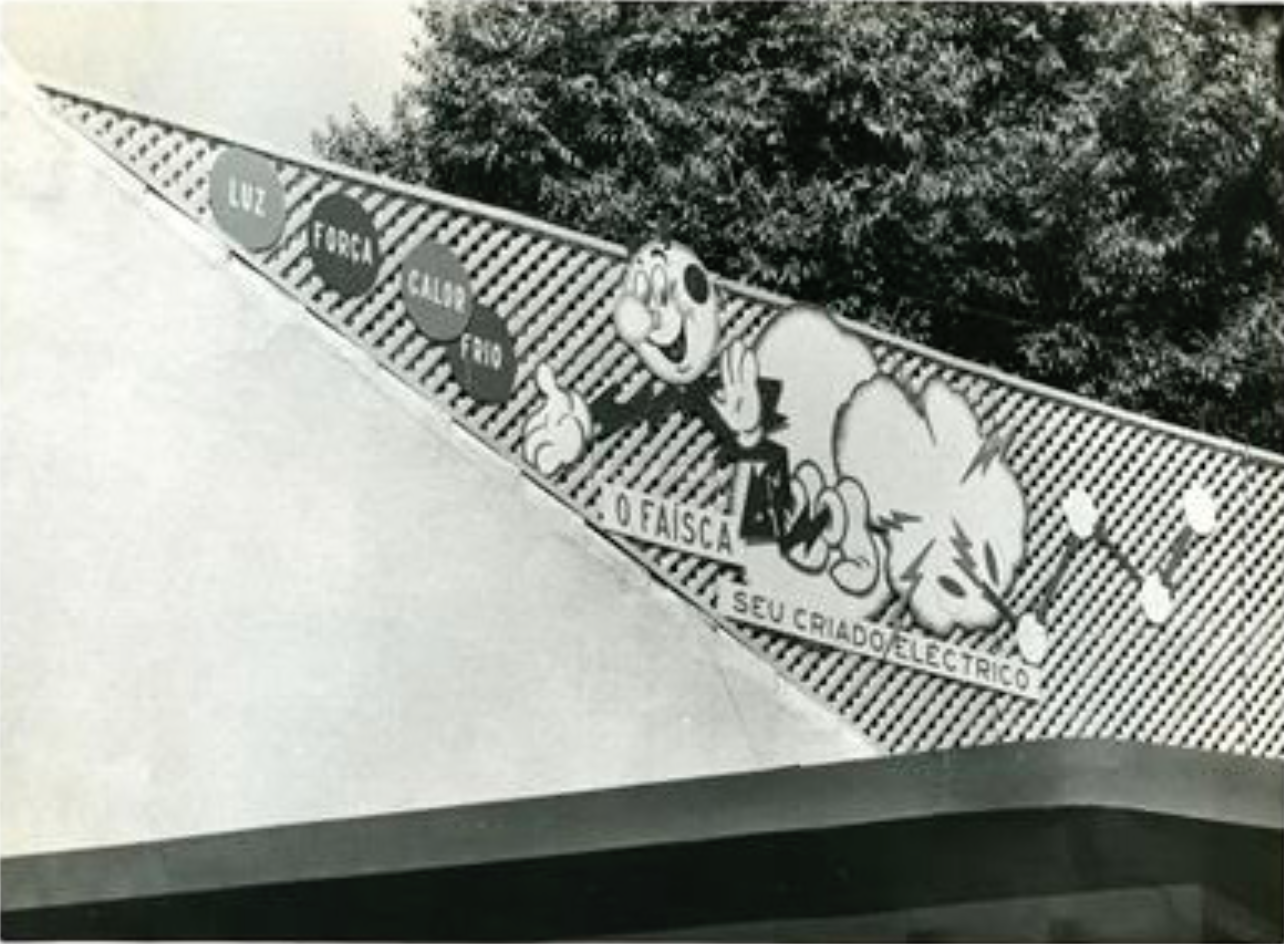

In the 1950s, CRGE put up a stand every year in Feira Popular, always displaying electrical appliances and gas-powered equipment. Beside the slogans “O gás e tão moderno como a aparelhagem que o utilizar” [Gas is only as modern as the equipment that uses it] (1951); “O gás, chama doctil e potente, é uma fonte de calor incomparável na economia doméstica” [Gas, that docile and potent flame, an incomparable source of heat in the household economy] (1951), were those connected to electricity: “Viva com toda a comodidade que a electricidade lhe pode dar” [Live with all the comfort that electricity can give you] (1953); “Rodeie-se da comodidade eléctrica. Tudo a electricidade” [Surround yourself with electrical comfort. All running on electricity] (1957). The character Faísca [Spark]72 became present in CRGE’s billboards and shop windows, with the slogan “Spark, your electrical servant”, enjoying great visibility at the entrance of the company’s shop in Feira Popular (1954) (figure 12). All these changes were directly connected to the goal of promoting electricity consumption based on the utilization of electrical home appliances.

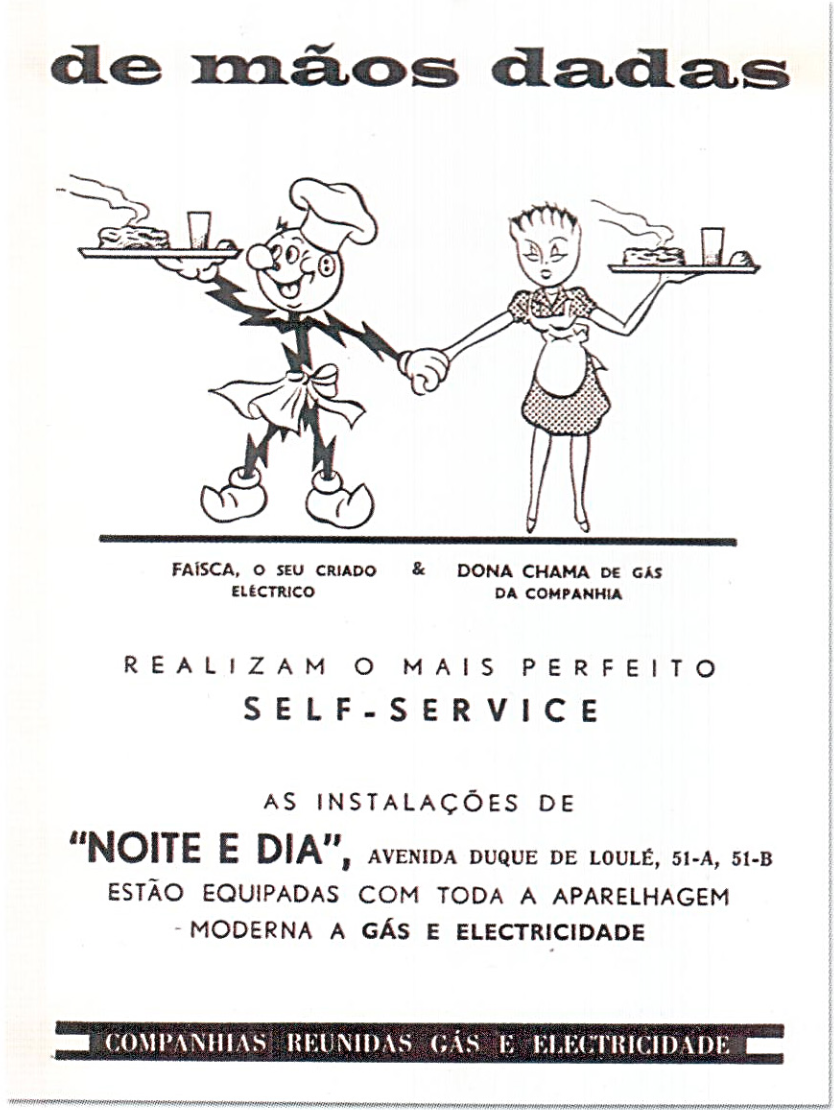

From 1957 onwards, CRGE’s advertising division was reorganized and its campaigns started to be designed for one-year periods. Aiming at a higher level of professionalism, CRGE in 1949 hired instructors for staff training courses.73 At that time, faced with competition from bottled gas, the character Faísca introduced “Dona Chama de Gás da Companhia” [The Company Gas Flame Lady] as part of its commercial strategy.

The fact that CRGE exploited gas and electricity in a market which avoided competition resulted in all advertising being made around these two different brand names - Faísca and Dona Chama -, usually appearing in billboards, adverts and brochures hand in hand or working together, so as to convey to consumers the idea that these two modes of energy were complementary, not mutually exclusive (figure 13). Although energies are represented by different genders (electricity man, gas woman) these representations were more connected to an articulated modernization between two kinds of energy, than to a division between modern and traditional. On the other hand, reacting to the appearance of bottled gas in the 1950s, CRGE developed a strategy to identify the city with the gas that it supplied, repeatedly using the slogan “Gás da Companhia – O combustível de Lisboa” [Company Gas – the Fuel of Lisbon].74 Other, less direct forms of promoting electricity consumption were developed in the Cold Campaign at Cinema Tivoli – a refrigerator exhibition made in partnership with several different brands (Westinghouse, General Electric, Siemens, Kelvinator, etc.), with refrigerators being sold in instalments. In addition, CRGE was present at other exhibitions: the Salão das Artes Domésticas [Domestic Arts Show] (1957 and 1958) organized in Junqueira, and the Exhibition at the José Alvalade Stadium75 (1958).

©Centro de Documentação da Fundação EDP

In 1960, the magazine Crónica Feminina [Women’s Chronicle] showed both the adverts of CRGE and those of some refrigerator manufacturers (Frigidaire and Siemens), complementing one another. While the CRGE ads spoke of refrigerators – with no mention of brands – and Faísca appealed to the housewife’s rationality by indicating that, with these appliances, they could buy the turkey when it was cheap and then eat it when they chose to, the ads by manufacturers in turn sometimes used information regarding the advantages of electrical home appliances, and never failed to stress the quality of their products, pointing out their brand as synonymous with quality: “Para quem exige o melhor” [For those who demand the best] (Siemens) and “Um produto da General Motors” [A General Motors product] (Frigidaire).76

In the 1960s, a significant rise in electricity consumption was accompanied by a growing use of electrical appliances in the home. CRGE’s commercial strategy of exhibitions and the Chiado showroom, plus an ever-expanding network of electrical appliance retailers - who in effect advertised these goods - contributed to a high percentage of electrified households.

Back to topWashing machines and TV sets as symbols of modernity, and the new role of women up to the 1970s

CRGE’s housewife-targeted advertising highlighted the increased speed and quality in meal preparation, easier cleaning and lower energy consumption, in the kitchen space. In the bathroom, the water heater was the main recipient of praise, while throughout the whole house the advantages of gas were publicized.

The cooking courses developed by Eva magazine and by CRGE in the 1930s sought to stress the idea that, thanks to the modernization of the kitchen by the use of gas, “diets became more varied, so cooking was more complex”.77 The existence of these courses confirms that housewives were expected to deliver increasingly elaborate meals, supposedly made easier by the use of gas stoves. From 1930 to 1959, Eva magazine kept in line with the principles propagated by the Estado Novo regime78, headed by Salazar, which upheld the traditional family and assigned to the wife “the sole responsibility over everyday family dynamics, through the timely preparation of meals, clothes maintenance and cleaning of the living spaces”.79

It is worth noting that the strategy developed by CRGE was copied by the bottled gas supplier GAZCIDLA, which from 1960 to 1977 published the magazine Banquete - Revista Portuguesa de Culinária [Banquet – Portuguese Culinary Magazine], which became a reference in Portuguese cooking. Thus, the companies that supplied energy helped construct the stereotype of the Portuguese housewife, who was supposed to devote a large amount of time to cooking meals, through the association between the utilization of modern energies and increasingly refined cooking.

In 1951, the application of declining block rates to electricity enabled a more widespread use of electrical appliances in Lisbon, and CRGE’s advertising shifted its focus to insist on tying the modernization of households to the use of both energies – gas and electricity.

From 1960 to 1973, the Portuguese economy experienced exponential growth, with GDP per capita rising at an average of 6.9% a year.80 CRGE’s efforts to promote gas and electricity were directed at housewives and insisted on the use of electrical appliances as crucial to the “modernization” of their homes. This idea came across very clearly at the Feira Popular, one of the leisure spots most frequently attended by the middle class, where electricity was presented under the slogans “Electricidade, o nervo da vida moderna” [Electricity, the nerve of modern life] (1964) and “Lar electrificado, lar moderno” (An electrified home is a modernized home) (1965).

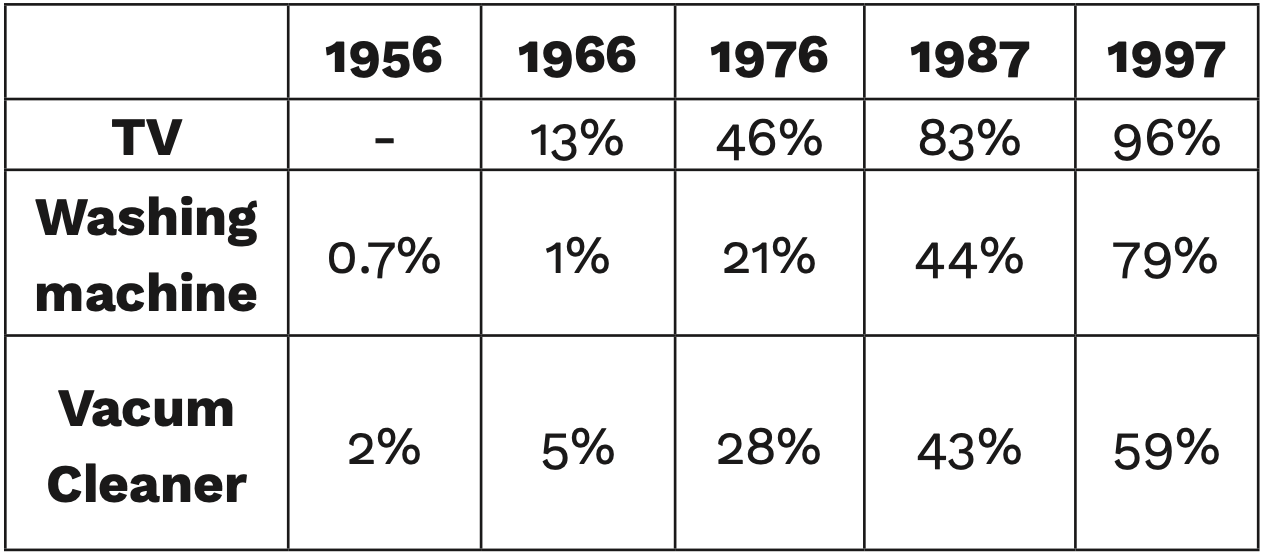

Some years earlier, in September 1956, the first television broadcast trials had taken place – not surprisingly, from a studio set up in Feira Popular.81 From that moment on, the TV became the star among domestic electrical appliances, quickly surpassing both vacuum cleaners and washing machines. As a consequence, the symbol of the home’s modernization was an appliance dedicated to leisure, instead of being designed to spare housewives some of their workload.82

Another paradigmatic example of the spread of electrical home appliances was the washing machine. In 194183, when the engineer José Ferreira Dias – the State Secretary for Trade and Industry who was the greatest promoter of the country’s electrification –carried out the experiment of “modernizing his home” with electrical appliances, he left out the washing machine, because it was too expensive.84 Price was indeed a factor that slowed down the diffusion of the washing machine; but the fact that washerwomen - who descended from old peasants and gardeners in the outskirts of Lisbon who came to town to sell bread and vegetables and took care of laundering85 - remained in existence until very late, made it possible to solve the issue of washing one’s clothes in a more economical way.

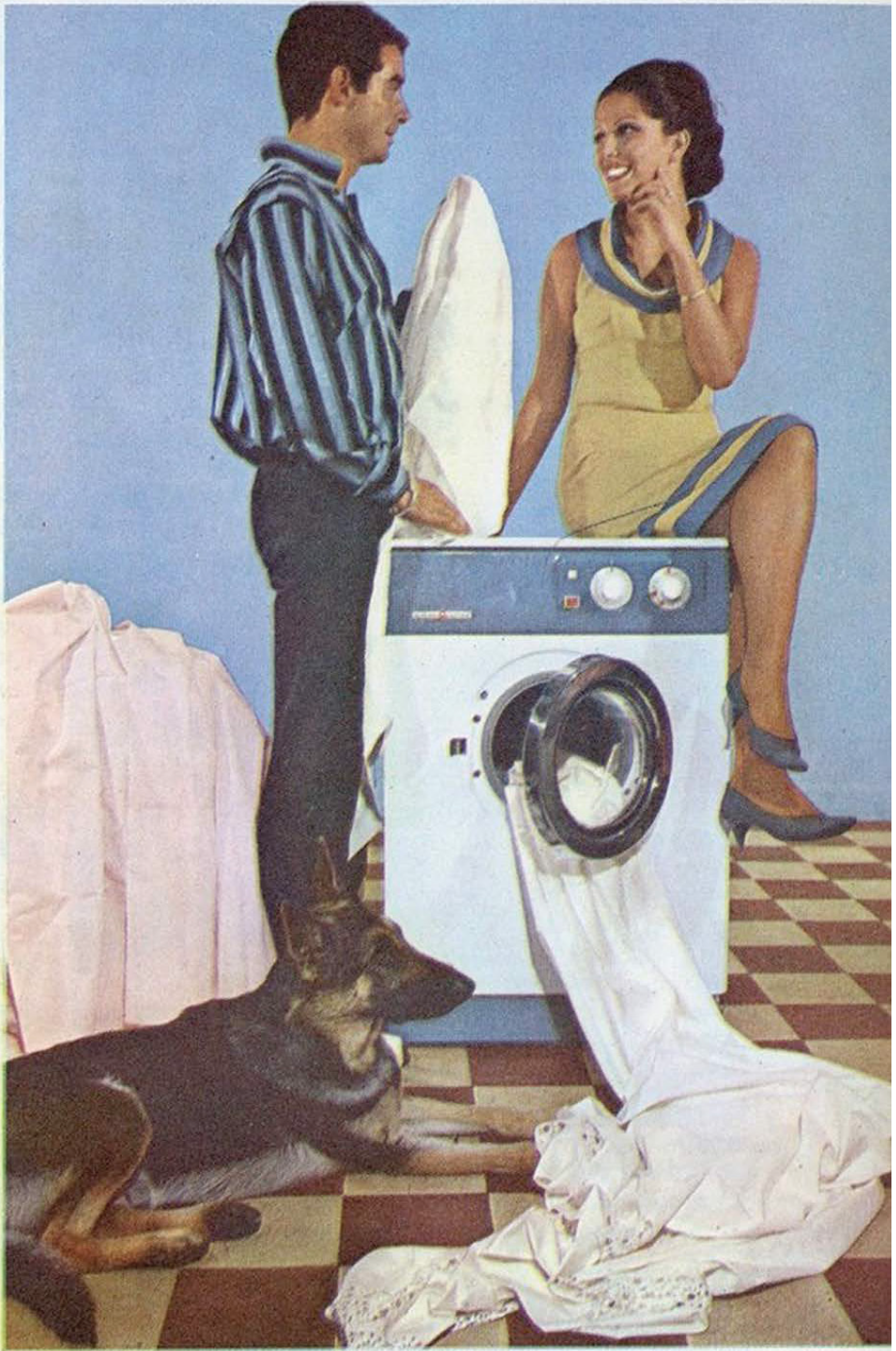

In May 1961, the CRGE shop window in the Chiado district advertised the washing machine using the slogan “O pior da lida da casa acabou-se! A máquina eléctrica lava a roupa depressa e bem” [The worst household chore is now over! The electrical machine washes your clothes quickly and efficiently].86 Despite these advertising efforts87, in 1966 only 1% of Portuguese families were in possession of this machine. The rising level of attention that this appliance got from advertising, coupled with the gradual disappearance of the traditional washerwomen, implied a very significant increase in washing machine purchases, so that by 1976, 21% of households already possessed one. Thus, only as late as the 1970s – with a delay of ten years relative to most European countries88 - the washing machine progressively made its way into middle-class homes.89 Towards the end of the century, almost every family counted one unit among its electrical appliances (figure 14). Although these figures refer to the whole country, the fact is that Lisbon, being its capital city, had a particularly high concentration.

The change from 1% to 79% in a 30-year timespan tells us that there was enough consumer desire for the washing machine. However, the quick incorporation of the TV set a decade earlier shows that first came the man’s wish to possess appliances for leisure and information, and only then, in second place, came those appliances which spared housewives some work.

Advertising records are also very explicit regarding the new reality of many Lisbon homes where, starting in the 1960s but especially midway through the 70s, housemaids were becoming scarce, a luxury only affordable by the haute bourgeoisie. This is why the maid was no longer featured in the ads, unlike previous decades whose ads showed her working with gas stoves or vacuum cleaners. Instead, the housewife herself could now be seen, in a pose of rest or ready to go out. From the 1960/70s on, a new vision of woman emerged in advertising – a sophisticated woman who carried out her household duties while at the same time dressing up impeccably, and often complementing those duties with some professional activity (figure 15). The stronger affirmation of feminist movements, the May 1968 revolution, rising levels of schooling and professionalization, all contributed to the appearance of some ads, as early as the 1960s, in which the husband collaborates, side by side with his wife, in performing household chores in perfect family harmony.

Conclusion

From 1891 onwards the distribution of gas and electricity in Lisbon was exploited as a monopoly by CRGE, which in order to increase gas consumption has developed a marketing policy creating a showroom, payments of appliances instalments and publishing advertisements in journals and magazines. However, until the 1920s the use of gas was mainly for public and private lighting and domestic gas appliances remained restricted to social groups with greater financial means, becoming an attribute of social status.

The marketing initiatives by CRGE developed in the 1930s, contributed to generalize the diverse uses of gas. Those campaigns suffered a clear influence from contemporary practices in France and led to the public’s embrace of new consumer values expressing the desire to have a modern kitchen “as if they lived in America”.

All these campaigns contributed to the very significant upward trend of the gas consumption after the World War II, and even, from the 1950s onwards, when electricity became more significant in domestic uses, gas managed to maintain its position.

The rationing of electricity consumption during World War II altered the previous trend to increase domestic electricity consumption. The text quoted in the first page of this paper, asking for lower electricity prices for “civilized people, who need it not for luxury but for making life easier”, should be understood as the effect of all the CRGE’s campaigns suggesting that a “modern home” should be equipped with “modern energy appliances” (gas and electricity).

From 1951 onwards, decreasing electricity prices made it possible to spread the use of electrical appliances widely, the TV set being the symbol of the Portuguese modern home. This was a local adaptation of the modern American home, that shows a nonlinear relationship between publicity and consumption. This opens up a path to study the diverse relationships between, on the one hand, the goals of the campaigns of gas and electricity companies and, on the other hand, public adherence to appliances powered by these energies.

The analysis of gas and electricity consumption in households in Lisbon, the capital of Portugal, led us to conclude that this consumption was not in competition but complementary, which is explained by the fact that the same company exploits the production and distribution of these two energies. This situation of complementarity is a particular case, both in Portugal and in the rest of Europe, since it does not occur in other cities in that country or in most European capitals.

This complementarity determined that marketing strategies to promote the consumption of energy in the home were oriented towards a division in which gas was mainly connected to the kitchen and bathroom and electricity was reserved for the home office space and the living room, where the radio and later the television had a prominent place oriented towards family leisure.

Thus, in symbolic terms, gas was associated with domestic chores, such as cooking and domestic hygiene (washing clothes, washing dishes and bathing the children), and is therefore represented by a female figure -Dona Chama-, while electricity was associated with lighting for reading and with information and leisure (radio and television). This complementarity is reflected in the campaigns launched simultaneously in the 1930s for the sale of electric irons, water heaters and gas cooking (figure 16).

This reinforced the stereotype of the housewife in charge of managing the home. Simultaneously, CRGE’s advertising promoted – by the adjectivisation – the idea that the use of gas and electricity symbolised a modern and comfortable home, contrary to what historiography has traditionally considered by placing the domestic use of electricity as progress in relation to the use of gas.

- 1. Eva, August 1946, 22-23.

- 2. Ruth Schwartz Cowan, More Work for Mother: The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Hearth to the Microwave (New York: Basic Books, 1983), 13.

- 3. Idem.

- 4. Mercedes Arroyo, La industria del gas en Barcelona, 1841-1933 (Barcelona: Ed. del Serbal, 1996).

- 5. Alain Beltran, Patrice A. Carré, La fée et la servante. La société française face à l’électricité XIXe-XXe siècle (Paris: Belin, 1991).

- 6. Jeanne Boin, "L’utilisation domestique de l’électricité. Soixante ans de conseils à l’utilisateur", in L’électricité et ses consommateurs. Actes du quatrième colloque de L’Association pour L’Histoire de L’Électricité en France (Paris: PUF, 1987).

- 7. Jane Busch, “Cooking Competition: Technology on the Domestic Market in the 1930s”, Technology and Culture, Vol. 24, N° 2, 1983.

- 8. Anne Clendinning, Demons of Domesticity: Women and the English Gas Industry 1889-1939 (New York: Routledge, 2004).

- 9. Yves Bouvier, "Energy consumers, a boundary concept for the history of energy", Journal of Energy History [Online], n°1, 2018, consulted 7 May 2021, URL : energyhistory.eu/en/node/86.

- 10. Ana Cardoso de Matos et al., A electricidade em Portugal. Dos primórdios à 2 Guerra Mundial, (Lisbon: EDP, 2004).

- 11. Diego Bussola, “A luz do capital. Sofina e a regulação da electricidade em Lisboa e Buenos Aires, no século XX” (Ph.D diss., University Institute of Lisbon, 2012).

- 12. Ana Cardoso de Matos et al., As imagens do gás. As Companhias Reunidas de Gás e Electricidade e a produção e distribuição de gás em Lisboa (Lisbon: EDP, 2005).

- 13. Diego Bussola, “A modernização dos lares lisboetas: consumo de energia e electrodomésticos na Lisboa de após guerra (1947-1975)” (Master thesis, University Institute of Lisbon, 2005).

- 14. Cardoso de Matos, As imagens do gás, 122.

- 15. CDFEDP, CRGE, Annual Board Report, 1898-99, 5.

- 16. Gas for engines was sold at a lower price.

- 17. It would be interesting to present a chart with gas consumption, however there´s no data available.

- 18. CDFEDP, CRGE, Annual Board Report, 1892-93 and 1904-05.

- 19. In December 1915, the scarcity and steep price of coal forced the company to raise the price of gas for lighting and engines, and to suspend the promotion by which private consumers were able to pay for cooking gas at lower rates. CDFEDP, CRGE, Management Board Minute Book, nr. 8, 1915-1922, 24.

- 20. CDFEDP, CRGE, Annual Board Report, 1916-1917, 5.

- 21. In that economic year, the company suffered losses of 767.627$614, due to the price of coal and its transportation, and to the increase in salaries and other expenses. CDFEDP, CRGE, Annual Board Report, 1917-1918.

- 22. Until the end of the 1930s the domestic use of electricity was very low, the iron being the only electric appliance with some relevance. In 1930 iron accounted for 13.1% of electrical consumers. Maria Helena de Freitas, Fernando Faria, Electricity and Modernity (Lisbon: EDP, 2000), 63.

- 23. With the same purpose the Compagnie parisienne de distribution de l’électricité (CPDE) lowered the rates by 43% for electricity. Beltran, Carré, La fée et la servante, 256.

- 24. Bussola, “A modernização dos lares lisboetas”, 27. Converting the rates from escudos to francs (fr.) and comparing with those in Paris: CPDE (Paris): 1° fr. 1.37; 2° fr. 1.00; 3° 0.237. CRGE (Lisbon): 1° fr. 3.06; 2° fr. 1.94; 3° fr. 0.81. CDFEDP, CRGE, “Commentaires sur les décret-lois concernant les nouveaux tarifs d’Energie électrique, en France”, 8 March 1939.

- 25. Sofia Teives, Diego Bussola, “O consumo doméstico de energia” in Nuno Madureira (ed.) A história da energia, Portugal 1890-1980 (Lisbon: Horizonte, 2005), 121.

- 26. CDFEDP, CRGE, Annual Board Report, 1892–1893, 6.

- 27. Francis Goodall, Burning to Serve: Selling Gas in Competitive Markets (Derbyshire: Landmark, 1999), 142.

- 28. Jean-Pierre Williot, Serge Paquier, “Stratégies entrepreneuriales et évolution des marchés des années 1840 aux années 1930”, in Serge Paquier, Jean-Pierre Williot (eds.), L’Industrie du gaz en Europe au XIXe et XXe siècles. Innovation entre marchés privés et collectivités publiques (Bruxelles: Peter Lang, 2005), 59.

- 29. CDFEDP, CRGE, Annual Board Report, 1892–1893, 6.

- 30. In Lisbon, at that point there were 13,848 gas consumers, so 36% had kitchen stoves. CDFEDP, CRGE, Annual Board Report, 1892–1893, 6-7.

- 31. CDFEDP, CRGE, Management Board Minute Book, 1907-1915, 132.

- 32. The first Electricity Congress was held in Lisbon in 1923 and its organisation came from the electricity section of the Associação Comercial de Lisboa (Lisbon Trade Association). At the end of this congress the organising committee for the 2nd congress was created and it was held in Oporto in 1924. Two other congresses were held in Coimbra in 1926 and Braga in 1930. On the subject see Ana Cardoso de Matos, “Formation, carrière et montée en puissance des ingénieurs électriciens au Portugal (de la fin du XIXe siècle aux années 1930)”, Marcela Efmertova, André Grelon (eds.), Des ingénieurs pour un monde nouveau. Histoire des enseignements électrotechniques (Europe Amériques) XIXe-XXe siècle (Bruxelles: Peter Lang, 2016), 400-402.

- 33. Beauchamp points out: “Shows in New York, in 1930s and 1940s, provided comprehensive exhibitions of electrical heating, refrigeration, air conditioning, cooking and laundry equipment, as well as radio and television” and “In the period up to 1939 a large number of small local exhibitions covering domestic appliances were held in London and the provinces”. Kenneth George Beauchamp, Exhibiting Electricity (London: IEE, 1997), 245-246.

- 34. Ana Mateus Malveiro, “Expor para divulgar. A memória das Exposicões de eletricidade e rádio e eletricidade realizadas em Portugal nas décadas de 20 e 30 do século XX” (Master thesis, Evora University, 2014), 92.

- 35. Among the various equipment representatives, we can mention the following: Singer showed electric sewing machines; Electrigia showed its Ormuz lamps; Casa Denis & Almeida exhibited the Frigidaire fridges; Siemens showed several electrical home appliances (irons, stoves, fans, loudspeakers, among others); Electro-lux exhibited its vacuum cleaners and floor polishers; Stubs & Guedes showed its cinematographic projection device Duoskop; Sampaio Baptista Lda. showed a model of an Otis elevator, just to name a few. Ibid., 93.

- 36. Almanach da Agencia Primitiva de Anúncios, Lisbon, 1873, 3.

- 37. Clendinning, Demons, 4.

- 38. Although the exact publication date of this brochure cannot be known for certain, it fell between 1895 and 1900. In the archives of the EDP Foundation there is a photocopy of the original, annexed to the work by Cunha Santos entitled “Informação sobre a Empresa”, s/d, a worksheet utilized in the company’s training initiatives.

- 39. O GAZ, Lisbon, CRGE, s/d, 2.

- 40. As Jane Busch argues “Electric ranges had not had the technological capability to compete seriously with gas until the 1920s.” Busch, “Cooking Competition”, 224.

- 41. As in other European cities too. For the Barcelona case see: Arroyo, La Industria del gas en Barcelona.

- 42. Beltran, Carré, La fée et la servante, 254.

- 43. On these campaigns in France see: Boin, “L’Utilisation domestique de l’électricité”.

- 44. Similar strategies were followed in other countries, such as the United States, where companies like General Electric, sought radio or film campaigns “were educational as well as entertaining”, Busch, “Cooking Competition", 238.

- 45. From the 1920s onwards, the number of radio sets in Portugal experienced an upward trend, rising from 20,000 in 1933 to around 100,000 in 1940. Ana Cardoso de Matos, Gonçalo Rocha Gonçalves, “A gravação sonora e a TSF em Portugal” in Nuno Luís Madureira (ed.), A História da Energia. Portugal 1890-1980 (Lisbon: Livros Horizonte, 2005), 214.

- 46. Cardoso de Matos, As imagens do gás, 153-154.

- 47. Busch, “Cooking Competition", 244.

- 48. As Scott suggests: “women were indeed present in the business world although they have been absent from the dominant narratives about it.” Joan W. Scott, “Comment: Conceptualizing Gender in American Business History,” Business History Review, vol. 72, n° 2, 1998, 244. Although it is not a central issue of our paper the female working staff of the CRGE, we can point out that the cooking courses that were part of the CRGE marketing strategies included women as a central part of promoting gas consumption: “Practical cooking courses by a specialized lady”, O amigo do lar, December 1932, 2.

- 49. O amigo do lar, January 1933, 8.

- 50. Diário de Noticias, 28th March 1925, 1. Quoted by Tânia Vanessa Araújo Gomes, “Uma revista feminina em tempo de guerra: O caso da “Eva” (1939-1945)” (Master thesis, Coimbra University, 2011), 5.

- 51. Ibid., 7. Although we do not have information about the print run for the whole period, we do know that the success of Eva continued and the print run of the Christmas special number grew from 50,000 (1939) to 120,000 (1967-1973). Bussola, “A modernização dos lares lisboetas”, 136-138.

- 52. Eva, December 1932, 47. It is worth stressing that the cooking courses, both those organized by Eva and those by CRGE, enjoyed a significant turnout.

- 53. Ibidem.

- 54. O amigo do lar, January 1933, 8. Some months before Eva’s cooking lectures, CRGE offered the same type of lectures in the Rua de Boavista at November 1932.

- 55. O amigo do lar, December 1932, 5.

- 56. Cardoso de Matos, As imagens do gás, 168.

- 57. O amigo do lar, January 1933, 8.

- 58. O amigo do lar, June 1937, 3-4.

- 59. As Joan Scott points out: “There's something going on (…) that needs thinking about in terms of how sexual difference is affirmed and produced through the creation and the service of consumer demand.” Scott, “Comment: Conceptualizing Gender”, 245.

- 60. O amigo do lar, July 1937, 16.

- 61. In 1936, 20% of electricity consumers had radios. See Freitas, Electricity and Modernity, 63.

- 62. UNIPEDE, 1932, 619-620. These were two case studies evaluating the usage of radio broadcasting.

- 63. UNIPEDE, 1936, 208.

- 64. O amigo do lar, July 1937, 3-12.

- 65. For SOFINA strategies and the role of domestic consumers see Bussola, “A luz do capital”, 145-149.

- 66. Jonas Frykman, Orvar Löfgren, Culture builders: A Historical Anthropology of Middle-class Life (New Brunswick: Rutgers, 1987), 127.

- 67. CDFEDP, CRGE, Management Board Minute Book, N°959, 27-3-1942.

- 68. Bussola, “A modernização dos lares”, 71-73.

- 69. CDFEDP, CRGE, Annual Board Report, 1947, 9.

- 70. CDFEDP, CRGE, Statistical Elements, 1947 and 1975.

- 71. Cardoso de Matos, As imagens do gás, 181-182.

- 72. This campaign was contracted by CRGE to the firm Ready, from the USA.

- 73. Cardoso de Matos, As imagens do gás, 182.

- 74. Eva, January 1959, 6.

- 75. This is the stadium of the Sporting Lisboa Football Team.

- 76. Crónica Feminina, 4-8-1960, 14; Crónica Feminina, 21-7-1960, 69; Crónica Feminina, 2-6-1960, 65.

- 77. Cowan, More Work for Mother, 99.

- 78. The “Estado Novo” was the political regime that existed in Portugal from the approval of the Constitution in 1933 until 25 April 1974. This regime also known as Salazarism, in reference to António de Oliveira Salazar, its founder, was characterised by being authoritarian, nationalist and corporatist.

- 79. Francisco Rodrigues, “O discurso da Eva: posicionamentos de uma revista feminina perante a condição social da mulher no Estado Novo (1930-1950)” (Master thesis, Porto University, 2017), 35.

- 80. In this period, Portugal’s PIB per capita as a percentage of OECD´s rose from 25% in 1960 to 37% in 1973. Edgar Rocha, “Crescimento económico em Portugal nos anos de 1960-73: alteração estrutural e ajustamento da oferta à procura de trabalho”, Análise Social, vol. 20, n° 84, 1984, 621-625. This was, therefore, a period of convergence of Portugal relative to OECD.

- 81. Fontes Carlos, “Feira Popular de Lisboa: diversão e poder” (Master thesis, University Institute of Lisbon, 1999), 137.

- 82. Bussola, “A modernização dos lares”.

- 83. In 1941, in the United States, 52 percent of the households had washing machines, and 47 percent had vacuum cleaners. Cowan, More Work for Mother, 94.

- 84. José Ferreira Dias, “Uma casa electrificada”, Boletim da Ordem dos Engenheiros, vol.50, 1941, 87.

- 85. Graça Índia Cordeiro, “Trabalho e profissões no imaginário de uma cidade: sobre os tipos populares de Lisboa”, Etnográfica, vol. 5, n°1, 2001, 18.

- 86. Note that the use of the name máquina de lavar roupa [clothes washing machine] wasn’t yet incorporated into everyday talk.

- 87. In 1953, an ad by Hoover showed the singer Amália Rodrigues using her washing machine. Eva, December 1953, 2.

- 88. In Barcelona, introduction of the washing machine was hindered by its high price. A generalized use of this appliance had to wait until the 1950/60s, “when the Barcelona marketplace saw the first automatic, Spanish-made machines, such as Tedi, Otsein, and Balay, as well as the various models of the pioneering Barcelona-made Bru washing machine”, Mercedes Tatjer Mir, “La electricidad en el lavado de la ropa doméstica y colectiva. Un lento proceso desde las lavadoras manuales hasta la difusión de las lavadoras eléctricas: Barcelona 1880-1990”, Capel Horacio, Zaar Miriam (eds.), La electricidad y la transformación de la vida urbana y social (Barcelona: UB/Geocrítica, 2019), 451. This phenomenon also took place in the 1960s in Britain when “the sale of domestic washing-machines also rose, to the extent that commercial laundries started to go out of business”, June Freeman, The Making of the Modern Kitchen: A Cultural History (Oxford: Berg, 2004), 45. As we mentioned, in these decades Portuguese families chose to buy television sets instead of washing machines.

- 89. An important aspect was the number of women per household. In Lisbon, taking into account housewives, servants and female relatives, in 1970 there was 0.92 women per household while in 1940 there was 1.5 women dedicated to housework per home. Bussola, “A modernização dos lares”, 84.

Araújo Gomes Tânia Vanessa, “Uma revista feminina em tempo de guerra: O caso da “Eva” (1939-1945)” (Master thesis, Coimbra University, 2011).

Arroyo Mercedes, La industria del gas en Barcelona, 1841-1933 (Barcelona: Ed. del Serbal, 1996).

Barreto António, A situação social em Portugal, 1960-1999 (Lisbon: ICS, 2000).

Beauchamp Kenneth George, Exhibiting Electricity (London: IEE, 1997).

Beltran Alain, Carré Patrice A., La fée et la servante. La société française face à l’électricité XIXe-XXe siècle (Paris: Belin, 1991).

Boin Jeanne, “L’utilisation domestique de l’électricité. Soixante ans de conseils à l’utilisateur”, in L’electricité et ses consommateurs. Actes du quatrième colloque de L’Association pour L’Histoire de L’Électricité en France (Paris, PUF, 1987).

Bouvier Yves, “Energy consumers, a boundary concept for the history of energy”, Journal of Energy History [Online], n°1, 2018, consulted 7 May 2021, URL: energyhistory.eu/en/node/86.

Busch Jane, “Cooking Competition: Technology on the Domestic Market in the 1930s”, Technology and Culture, vol. 24, n° 2, 1983, 222-245.

Bussola Diego, “A luz do capital. Sofina e a regulação da electricidade em Lisboa e Buenos Aires, no século XX” (Ph.D diss., University Institute of Lisbon, 2012).

Bussola Diego, “A modernização dos lares lisboetas: consumo de energia e electrodomésticos na Lisboa de após guerra (1947-1975)” (Master thesis, University Institute of Lisbon, 2005).

Cardoso de Matos Ana, “Formation, carrière et montée en puissance des ingénieurs électriciens au Portugal (de la fin du XIXe siècle aux années 1930)” in Efmertova Marcela, Grelon André (eds.), Des ingénieurs pour un monde nouveau. Histoire des enseignements électrotechniques (Europe Amériques) XIXe-XXe siècle (Bruxelles: Peter Lang, 2016), 381-406.

Cardoso de Matos Ana et al., As imagens do gás. As Companhias Reunidas de Gás e Electricidade e a produção e distribuição de gás em Lisboa (Lisbon: EDP, 2005).

Cardoso de Matos Ana, Rocha Gonçalves Gonçalo, “A gravação sonora e a TSF em Portugal” in Nuno Luís Madureira (ed.), A História da Energia. Portugal 1890-1980 (Lisbon: Livros Horizonte, 2005), 191-218.

Cardoso de Matos Ana et al., A electricidade em Portugal. Dos primórdios à 2 Guerra Mundial (Lisbon: EDP, 2004).

Clendinning Anne, Demons of Domesticity: Women and the English Gas Industry 1889-1939 (New York: Routledge, 2004).

Cordeiro Graça Índia, “Trabalho e profissões no imaginário de uma cidade: sobre os tipos populares de Lisboa”, Etnográfica, vol. 5, n°1, 2001, 7-24.

Cowan Ruth Schwartz, More Work for Mother: The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Hearth to the Microwave (New York: Basic Books, 1983).

Freitas Maria Helena de, Faria Fernando, Electricity and Modernity (Lisbon: EDP, 2000).

Ferreira Dias José, “Uma casa electrificada”, Boletim da Ordem dos Engenheiros, vol. 50, 1941, 33-43; 85-94.

Fontes Carlos, “Feira Popular de Lisboa: diversão e poder” (Master thesis, University Institute of Lisbon, 1999).

Freeman June, The Making of the Modern Kitchen: A Cultural History (Oxford: Berg, 2004).

Frykman Jonas, Löfgren Orvar, Culture Builders: A Historical Anthropology of Middle-class Life (New Brunswick: Rutgers, 1987).

Goodall Francis, Burning to Serve: Selling Gas in Competitive Markets (Derbyshire: Landmark, 1999).

Malveiro Ana Mateus, “Expor para divulgar. A memória das Exposições de eletricidade e rádio e eletricidade realizadas em Portugal nas décadas de 20 e 30 do século XX” (Master thesis, Evora University, 2014).

Rocha Edgar, “Crescimento económico em Portugal nos anos de 1960-73: alteração estrutural e ajustamento da oferta à procura de trabalho”, Análise Social, vol. 20, n° 84, 1984, 621-644.

Rodrigues Francisco, “O discurso da Eva: posicionamentos de uma revista feminina perante a condição social da mulher no Estado Novo (1930-1950)” (Master thesis, Porto University, 2017).

Scott Joan W., “Comment: Conceptualizing Gender in American Business History”, Business History Review, vol. 72, n° 2, 1998, 242-249.

Tatjer Mir Mercedes, “La electricidad en el lavado de la ropa doméstica y colectiva. Un lento proceso desde las lavadoras manuales hasta la difusión de las lavadoras eléctricas: Barcelona 1880-1990”, in Capel Horacio, Zaar Miriam (eds.), La electricidad y la transformación de la vida urbana y social (Barcelona: UB/Geocrítica, 2019), 444-459. http://www.ub.edu/geocrit/Electricidad-y-transformacion-de-la-vida-urba… (accessed 02/06/2020)

Teives Sofia, Bussola Diego, “O consumo doméstico de energia” in Nuno Madureira (ed.) A história da energia, Portugal 1890-1980 (Lisbon: Horizonte, 2005), 115-140.

Williot Jean-Pierre, Paquier Serge, “Stratégies entrepreneuriales et évolution des marchés des années 1840 aux années 1930”, in Paquier Serge, Williot Jean-Pierre (eds.), L’Industrie du gaz en Europe aux XIXe et XXe siècles. Innovation entre marchés privés et collectivités publiques (Bruxelles, Peter Lang, 2005), 53-64.