Labour and social protection in the Romanian oil industry during the Interwar

Petroleum-Gas University of Ploiești, România

calcangheorghe[at]yahoo.com

This paper analyses employee needs in the Romanian oil industry during the interwar period. Three distinct periods will be explored: the aftermath of the First World War, the economic crisis of 1929-1933, and the outbreak of the Second World War. I will also present several pol- icies implemented by oil companies to ensure the well-being of their employees, as well as data on the number of workers in this industry.

Introduction

Romania was an important European oil producing country,1 and began its presence in the industry in 1857 with three world firsts: the first officially recorded oil production, the first modern refinery, and the first oil-lit capital, Bucharest.2 Romanian oil production increased from 275 tons in 1857 to approximately 1.9 million tons in 1913, and 8.7 million tons in 1936.3 During the interwar period, Romania ranked between 4th and 6th in world oil production and exports, and the 2nd in Europe after the former Soviet Union.

While the amount of oil exported was not high in percentage terms on the global level, it was considerable on the regional level. For example, in 1931 nine states from the region and the Near East procured over 50% of their domestic oil needs from Romania.4 In 1936, Romania exported petroleum products to almost 50 countries across the globe. Its geostrategic importance was highlighted in the context of the two World Wars, when the oil industry was subject to unprecedented internal and external strategies.5

During the interwar period, the government sought to increase national influence over this industry, which at the time was dominated by foreign capital. In 1914, Romanian capital represented only 8.10%, compared to 27.32% for German capital, 24.26% for Dutch capital, and 23.63% for British capital, among others. After targeted legislative policy, Romanian capital increased towards the end of the interwar period to 26.16%, as compared to 20.62% for British capital, 16.21% for Anglo-Dutch, 15.49% for French, 10.10% for American, 6.44% for Belgian, 3.47% for Italian, and 0.38% for German capital, among others.6

In the period following the Second World War, Romania reached its peak oil production of 15 million tons between 1975-1977.7 After the collapse of the communist regime in Romania, oil production fell steadily, reaching around 3.5 million tons of crude oil per year today.8

This paper highlights several aspects connected to the personal and collective needs and aspirations of employees in the Romanian oil industry during the interwar period. It addresses the issue of social protection in three different periods. The first part of this study examines social regulations in the oil industry after the First World War, focusing on three distinct issues as detailed below. The second part analyses the general economic crisis of 1929-1933, with its effects on employees in the oil field. The third part is devoted to the context of the Second World War, which led to the impoverishment of most employees.

This study is based on the Moniteur du pétrole roumain, the most important publication of the Romanian oil industry of that time,9 the archival collections of the main oil companies in the National Archives, as well as the relevant literature.

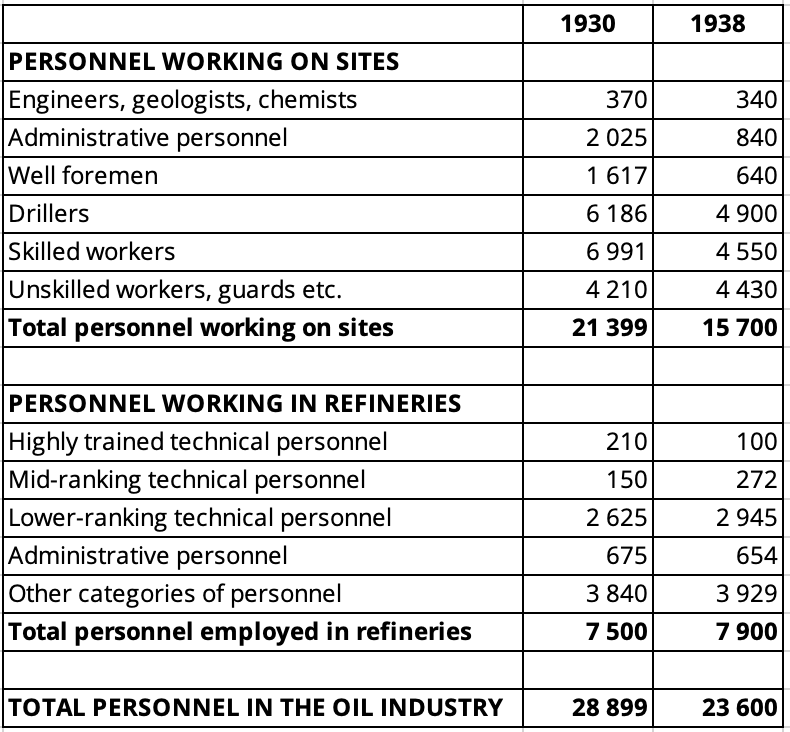

An accurate picture of the number of employees working in the interwar Romanian oil industry can be established using the data in the following table, with 1930 and 1938 serving as reference points (Figure 1).

The number of employees decreased from 28,899 in 1930 to 23,600 in 1938. This number continued to fall during the Second World War, reaching 18,500 people in 1940. The maximum number of employees in the interwar period was in 1929, with a total of 30,170 employees working in the oil industry.10

Back to topSocial regulations after the First World War

The period following the First World War was generally characterized by a more democratic society, a trend that manifested itself in the oil industry as well. The Law of Universal Suffrage of 1918, the right to ownership for peasants provided by the law of 1921,11 and the new Constitution of 1923—which enumerated the civil rights and freedoms specific to any democratic state—are some of the essential landmarks of this democratic process.12 Others include the regulations codified in Sunday rest laws, as well as the establishment of the Chambers of Labour (a national institution regulating the employee–employer relationship) and social security norms. These laws were applicable to the entire national economy, and not just the oil industry. We will analyse these policies and their impact on the Romanian oil industry.

Reactions from oil industry representatives to the Sunday Rest Law

The first Sunday rest law in Romania was adopted in 1897, and provided for an exemption from work for the first half of Sunday morning. The law underwent several changes throughout the years. Following the recommendations of the International Labour Conference in 1921, partial regulations were implemented in 1923, and more profound ones via the Law regarding the Regulation of Sunday Rest and of Legal Holidays dated June 18, 1925. The law required all industrial and commercial enterprises to grant their employees a 24-hour rest every Sunday.13

On June 26, 1925, the Association of Petroleum Industrialists of Romania addressed a memorandum, signed by its president, the engineer Constantin Osiceanu, to the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare regarding the effects of the Sunday rest law on the oil industry.

The Association operated throughout the interwar period, representing all companies from the oil industry. It actively promoted the interests of oil companies in their struggle with the state, and regularly organized conferences, drafted petitions, solicited hearings at the ministry, and requested facilities for oil exploitation, trade, and export, among other things. No legislative initiatives, decisions, or regulations were adopted by the ministry, or laws passed by the Parliament, without a reaction or intervention on the part of this association. It constantly demanded that the state reduce various taxes imposed on the industry, asking it not to see the oil industry as the “goose that laid the golden egg.” The association spoke on behalf of the entire industry, which ensured its status as a social partner that could not be ignored by the state.

However, a division occurred with the adoption of the main mining laws in 1924, 1929, and 1937: companies with majority foreign capital and those with majority Romanian capital chose to form separate groups with separate reports. For example, in connection with the draft of the new mining law of 1924, which provided for the nationalization of subsoil resources and incentives for Romanian capital and personnel, the memorandum issued by the foreign-owned companies was signed by 25 oil companies, including “Astra Română,” “Româno-Americană,” “Aquila Franco-Română,” “Colombia,” “Petrol Block,” “Româno-Belgiana,” etc., while the memorandum issued by companies with Romanian capital was signed by 23 oil companies, including “Creditul Minier,” “România Petroliferă,” “I.R.D.P.,” “Petrolul Românesc,” and “Prahova.”14 However, with respect to social insurance, there were no differences between the position of companies with foreign capital and those with Romanian capital.

The law of 1925 completely banned work on Sundays and public holidays, except for certain enterprises specified in the law (art. 7). Oil exploration was not included among these exceptions. The memorandum included relevant examples of several activities relating to the extraction of oil, such as the handling of well pipes, which could not be performed on rest days. However, a provision in the law allowed for swapping Sunday or a public holiday with another day of the week for those employees required to work on those days, with authorization from the Chambers of Labour (art. 11).

The report by the Association of Petroleum Industrialists noted that the Chambers of Labour had not yet been established. Administrative authorities were nevertheless expected to comply with the provisions of the new law, and to therefore prohibit work on Sundays and public holidays. The association subsequently requested permission to operate oil facilities and carry out emergency operations, all while complying with the provisions in article 11 of the law. It is noteworthy that this memorandum was addressed to the ministry shortly after publication of the law in the Official Gazette.15

It should be pointed out that for activities and industries requiring permanent activity, exemptions from the principle of legal rest periods were perfectly justifiable; we should therefore consider the approach adopted by the Association as being appropriate. The oil industry successfully obtained such exemptions throughout the interwar period.

The adoption of Sunday rest was a necessity, and was embraced by Romanian society. The National Liberal Party (PNL), which was the party in power at that time, included it among its democratic achievements, and the National Peasants Party (PNȚ) defended the law when it was part of the government, while the socialist movement and employees saw this law as “a conquest.” Employers understood the necessity of the law, respecting it and its principle.16

Reactions of oil industry representatives to the establishment of Chambers of Labour

In post-war Romania, several attempts were made to regulate relations between workers and their employers, including the establishment of Chambers of Labour. In addition to founding such relations on new principles, consideration was also given to alignment with European legislation in the field, as Chambers of Labour had already been created in France, England, and Italy in the late nineteenth century, and in Austria in the early twentieth.17

The first consistent initiatives came from the liberals, who had already pursued a strategy of gaining the trust of the working class. When they were in charge of the government from 1922-1926, two bills establishing Chambers of Labour were developed, in 1923 and 1925, with involvement from various Ministers of Labour. Neither of the bills became law, as they garnered support neither from workers nor employers.18

The debates connected to bills proposing the establishment of Chambers of Labour generated serious concern from the Association of Petroleum Industrialists in 1925. On June 9, 1925, the association submitted a substantial memorandum to the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare, shortly after the draft version of the new law had been debated and passed by the Senate. The Association indicated that it “had not been informed about the bill,” a statement that carried weight, as it came from the most important industry in the country.

During its initial objections, the Association seemed sympathetic, agreeing with the idea proposed by the Ministry in its Explanatory Memorandum, namely that there should be collaboration between employees and employers with respect to labour legislation. The association realised that continuing democratic change called for laws to be validated by those to whom they apply. Moreover, the interest of the state with respect to all its citizens was not to be neglected.

However, there was confusion surrounding the creation of “ad hoc bodies, without the consent of interested parties,” such as the Chambers of Labour and their governing boards. As institutions founded on the national level, these new Chambers had the advantage of being coherent in how they were established and operated. Nevertheless, according to the memorandum, there were many disadvantages, the most important one being “a total lack of homogeneity,” as the new bodies included “workers from industry, agriculture, trade, as well as manual labourers and intellectuals; these people, apart from the fact that they work to earn a living, have nothing in common.” The Association therefore wondered, “what kind of discussions could be held, and especially what kind of decisions could be made by such a heterogeneous group?”

Later remarks from the Association became extremely harsh, ultimately stating at the end that “your project, meant to enshrine harmony and social peace, will lead to a state of almost permanent agitation among our working classes.”19 Further comments emphasized a scenario characterized by instability: when workers were called to designate their representatives every four years, ideas, discussions, and conflicts would eventually be transferred to the general councils. As a consequence, the activity of the governing bodies would be blocked, and the ministry would intervene by organizing new elections after an interval of three months, thereby shattering social harmony.

Distrust of the association extended to the provision stipulating that, in the event of disputes between employees and employers, they would be resolved by the General Council of the Chambers of Labour, with the issued being discussed and solved by an equal number of workers and employers. The association believed that “such discussions will rarely lead to anything but a worsening of relations.”

In addition to these drawbacks, which the Association recapitulated in its memorandum, was the fact that the new Chambers of Labour established by law “will represent a heavy financial burden” for the industry. “All these elections, all these general councils and their sections and directorate committees, all the dynamics created by such a complex activity, will require considerable budget expenditure, which will ultimately have to be borne by oil producing companies.”20

The association believed that the professional associations existing at the time—organizations representing employers and employees—could very well carry out the activity and responsibilities provided for in the draft law for Chambers of Labour.

The memorandum concluded with the hope that the ministry “will consider the matter still worthy of discussion and reflection,”21 and would give the association the possibility to return with much more developed proposals, as the oil industry was experiencing difficulty at the time, and could put the money to more useful purposes.

Obviously, the memorandum voiced the association’s conservative and reluctant position towards the bill establishing the Chambers of Labour. The association was responsible for the bill not being adopted and for a lack of political consensus, in addition to the divergent interests of industrialists and employees.

In 1927, The Party of the People, the ruling party at the time, drafted a new bill for the establishment of Chambers of Labour, with contributions from the ministry. Although this bill did not substantially differ from that of the Liberals’, it was passed and became a law. Nevertheless, it could not be implemented due to financial reasons, as the budget came exclusively from employee contributions, with none from the state or employers.

The Chambers of Labour were established in 1932, by the law of 10 October, whose author, D. R. Ioanițescu, was a representative of the ruling party, The National Peasants Party. The chambers consisted “exclusively” of worker representatives and had consultative powers, under which it could inform authorities about the situation of employees, as well as administrative powers, under which it could collaborate with public authorities in the enforcement of labour laws. The law of 1932 provided for the representation of the Chambers of Labour in the Senate, the upper house of the Parliament. The 1932 law surpassed not only earlier Romanian bills, but through the representation of chambers in Parliament, also many similar laws abroad.22

The Liberals modified the law in 1934 by enlarging the social and professional categories included in the Chambers of Labour, as well as by changing the election process to subordinate management bodies. Furthermore, in 1936, they limited the unconditional right of Chambers to take part in Labour inspections. The establishment in 1938 of the authoritarian regime of King Charles II visibly diminished the powers and role of Chambers of Labour, and oriented all of Romanian society on a fairly corporate basis.23

The activity of Chambers of Labour was consistent with the provisions of the law, and oversaw the application of labour legislation, in addition to the observance of Sunday rest, albeit without generating spectacular improvement in the oil industry.

Reactions of the oil industry to social security

Another area affecting employees in which professional associations expressed their points of view was social security. In 1918, the Romanian provinces under foreign domination, namely Bessarabia, Bukovina, and Transylvania, united with Romania, which generated a vast process of administrative and legislative unification.24

An important chapter of this unification was that of social insurance. Until legislative unification was finally achieved, each united province continued to apply the legislation of the states to which it previsously belonged. Hungarian and Austrian laws were applied in Transylvania and Bukovina, Russian laws in Bessarabia, and old Romanian laws in the former Romanian Principalities, resulting in a wide variety of social insurance systems. Transylvania and Bukovina benefited from more advantageous provisions for employees that were closer to European standards than those of old Romania,25 while Bessarabia had legislation that was even more restrictive than that of Romania.

Domestic political life could not skirt the issue of labour legislation and social protection. On the contrary, as the working class played a major role in supporting the war effort and the process of restoring the country’s economy, the precarious material conditions after the war gave rise to broad protests and strikes in both Romania and Europe.26 Political parties played the role of working class “allies”: the PNL,27 the PNȚ, and the Party of the People,28 which had been mostly responsible for governing in interwar Romania, proceeded in a similar manner.

The legislative unification of social insurance in Romania was completed in 1933 (after unsuccessful attempts in 1925 and 1930). However, a series of laws had been adopted prior to 1933, and represented important steps towards the definitive unification of legislation in this field. The most significant of these were the following: the Law for the Regulation of Collective Labour Conflicts (1920), the Law on Trade Unions (1921), the General Pensions Act (1925), the Law for the Organization of the Labour Inspection Service (1927), the Law on Children’s and Women’s Labour Protection and Working Hours (i.e. 8-hour workday, 1928), etc. The unification process can be directly linked to the establishment of the new Ministry of Labour and Social Protection (30 March, 1920),29 a first in Romanian governmental activity.30

Information regarding social conflicts in the oil industry is scarce and disparate, and there is no work focusing on this topic in the specialized literature. Occasional information provided by the Moniteur du pétrole roumain gives the reader certain orientations and nuances.

In early 1926, the Ministry of Labour and Social Protection drafted a bill to this effect, triggering an instant reaction from interested parties and public opinion. On 10 February, 1926, shortly after the publication of this draft, the Association of Petroleum Industrialists addressed a memorandum to the Ministry of Labour and Social Protection. The prompt reaction was due to the fact that oil industry representatives believed they were “unfairly treated” compared to other industries, as “this industry has to face incomparably greater difficulties.”

The memorandum stated that both the bill and accompanying explanatory statements were already familiar to the sector. The oil industry was already supporting workers protection, stating that “we have made and are making great sacrifices to raise their standard of living, considering that the working class is an indispensable element for the development of the oil industry and, consequently, of national prosperity.”31

While everything seemed fine in principle and according to public statements, analysis of details and concrete activities suggests otherwise. The Association of Petroleum Industrialists felt that the bill would ascribe “major and multiple tasks” to the industry. If such obligations were to take effect, “we must definitely prove” that the oil industry cannot bear them “without endangering its very existence.” According to the memorandum, the oil industry was going through difficult times, due to the increased costs for materials and labour, as well as “enormous taxes.” In addition, the industry could not offset the newly imposed obligations by setting appropriate prices for petroleum products. One argument that it would be impossible to recover social protection expenses was based on the fact that 70% of petroleum products were destined for export, with prices in this segment “[being] dictated” by the external market. The potential losses were considered effective and irrecoverable. In turn, domestic consumption could not bear higher prices, as this would ultimately lead, according to the memorandum, to a higher cost of living in Romania.

With respect to the situation, the association proposed the following demands:

1- for accident insurance, authorities in the oil industry would have full autonomy, and they requested “the broadest possible autonomy” for insurance for sickness, old age, and disability, both under state control;

2- in order to establish insurance, employers must be in direct contact with workers, with no intervention by any other institutional body;

3- employers should be represented by delegates in all insurance committees and councils, according to their financial contribution;

4- insurance would apply only to manual workers;

5- the excessive financial obligations imposed on the oil industry should, in particular, be reduced “significantly”.

The memorandum calculated the money to be paid by the oil industry for sickness, disability, and accident insurance, giving concrete figures. The total sums would increase under the law’s extended coverage for accidents outside of actual working hours, as well as “various diseases considered to be accidents.” The increased maximum limits for pensions and annuities, along with higher administrative costs relating to the management of these new types of insurance, which would be borne by new bureaucratic structures, would ultimately lead to higher expenses.

In conclusion, the memorandum demanded that the draft law on social security be amended according to recommendations expressed by the Association of Petroleum Industrialists, as “its application in the current form will represent a serious shock for all of the country’s industry, and especially for our oil industry.”32 The memorandum was signed by engineer Constantin Osiceanu, the president of the association, and, as reported by Monitorul Petrolului/ Oil Gazzette, by the country’s main oil companies as well, which remained unnamed in the document.

The memorandum gives a strong sense of the reluctance and even opposition of oil industry employers towards the bill’s provisions. The bill was apparently driven by a much more open spirit, covering a wider range of employees from the oil sector and related activities. However, the issue of oil industry taxation was not new,33 as the state sought to cover as much of its needs as possible at the expense of industry in general, and at the expense of the most profitable and expanding one in particular. The oil sector was undoubtedly profitable, and, in this context, the state would become the arbiter balancing and harmonizing the interests of all its citizens.

With respect to employee protection policy, the tension between oil companies and the state was obvious, as both parties tried to conserve their financial resources and to obtain advantages. In the dynamics of this relationship, the state proved closer to the interests of oil industry workers.

In connection with debates on social protection, it is important to note the initiative of engineers from the Câmpina oil centre, who extended an invitation to their colleagues from Ploiești to hold a discussion on old-age insurance for engineers. The debate took place in Câmpina on 20 March 1926. The aim was to reach a joint approach for engineers in both the petroleum and mining industries, members of the Association of Mining Engineers. The goal was to increase their chances of success, since the two fields were so closely related. It was finally decided that these engineers would draft a variant of the bill and submit it to the Association of Petroleum Industrialists for further action.34

Several bills were drafted during the debate on social protection, including those submitted by the Association of Oil Industrialists, the General Union of Industrialists, the Ministry of Labour and Social Protection, as well as proposals on behalf of workers and employers in the oil industry. The Monitorul Petrolului/ Oil Gazzette presented the project co-authored by the Association of Oil Industrialists.

This project was carried out by a commission of the Bucharest Chamber of Commerce and delegates from the oil industry (engineers Eugen Saladin, Page, and M. Zentler).35 The commission was active for four months, from February to May 1926.

The bill consisted of two parts. The former included the Organization of Social Insurance, and provided for participation from both employers and the working class in organizational activity. All collective bodies (councils, committees etc.) would include representatives of workers, employers, and the state. Wherever it was deemed necessary, Social Insurance Houses or Insurance Offices could be established. In case of litigation, the draft provided for the existence of two courts.

The latter part of the bill dealt with social security and included three chapters, as follows: a) Sickness, maternity, and death insurance; b) Invalidity and old-age pension insurance; c) Accident insurance.36

After considerable efforts, a law authored by D. R. Ioanițescu regarding the unification of social insurance was passed. It was welcomed across the country’s political spectrum, including employers. It introduced the principle of compulsory insurance, and standardized risk categories at the provincial level (such as illness, maternity, death, accidents). It also unified the contribution to be paid, equally imposed the creation of the insurance fund on workers, employers, and the state, and enlarged the field of insurance, among others.37

The provisions of the law reflected the spirit of the debates on social insurance that had been held over the years in Geneva (1921, 1925, 1927, 1932). They aimed to align Romanian legislation with the “principles of more advanced countries, and with a more developed social culture.” It is also worth mentioning that the International Labour Office was especially consulted for the law of 1933, with this law preserving the advantages provided for in the international conventions that Romania had already ratified.38

There is not a great deal of information about the effects of the social security law, but it is possible to get some idea by looking at the analysis conducted in 1936 regarding the insurance situation in the mining field. By analogy, one can deduce that the situation was similar in the oil industry, as the two sectors were very close, and often intersected. Moreover, the same figures were present in the activity and management of both.

On 26 March 1936, as part of a series of conferences organized by the Ploiești regional branch of the Association of Mining Engineers, the engineer D. Filipescu, who was the director of the Concordia Oil Company, held a conference on social security in the mining industry. The speaker pointed out that the proposal made during debates connected to the law (1920-1926), namely that both employers and workers should contribute to the establishment of the Insurance House, did not become a reality.

Filipescu deemed the activity of the Houses of Economy, Pension, and Aid as being satisfactory. The presentation shows that the Houses that were created and operated alongside big companies had better results, which is logical given that more funds were raised by these companies. The way these houses used the funds (and the deposits) was considered very advantageous, “as a pension could be provided to the insured and their family, even reaching 60% of basic salaries.”39

In the same presentation, Filipescu highlighted the disadvantages of private pension funds in the event an employee changed jobs. Moreover, he considered it regrettable that not all industrial companies had set up Pension Houses. D. Filipescu also suggested setting up other forms of insurance, such as Support and Pension Houses within existing insurance and reinsurance companies. “The insurance policies would be owned by the employee, who would pay 50% of the respective premiums, the rest being paid by the employer. When leaving the service, the employee would keep his policy and would continue to pay the contribution.”40

Such efforts sought to improve the situation for old-age insurance and family members in case the insured person died.

Two important conclusions can be drawn from Filipescu’s presentation in 1936, The former stated that social security policy had positive effects, amounting to up to 60% of the pensioner’s salary, and the latter was that the social security system was not sufficiently developed, and therefore, called for other forms of organizing.

In 1938, a new law was adopted whose provisions were more generous than those from 1933, although the international context did not allow for its effects to be felt.41

While there was a significant disparity between legal provisions and the real situation,42 the adoption of social protection legislation was carried out within the international spirit of the time, as well as within its limits.43 It was a positive fact, as it helped to significantly improve working conditions and the lives of employees in general, and of employees in the oil industry in particular.

Back to topEffects of the 1929-1933 economic crisis on oil industry employees

The second period that will be addressed in this paper is the general economic crisis of 1929-1933, with particular focus on the personal needs of oil industry employees. Despite increasing oil production during that time, oil prices fell drastically, as follows: in 1931-1932, they were four times lower than those from 1927, and almost five and a half times lower than those from 1924. Unemployment enrolled 2,368 people in 1931, and in the same year, the total number of employees working in the oil industry represented only 45% of total staff from 1924,44 which gives an idea of the poor material conditions in which people lived. The multitude of dismissals generated a series of conflicts, first of an administrative and legal nature, and afterwards in the forms of strikes, riots, and physical violence.

For example, the oil monitor reported the dissatisfaction of those who had been temporarily hired for masonry works or road maintenance. Arbitration proceedings were not decided in their favour, and they were subsequently dismissed. On 1 February 1933, some of them were part of a group that caused material damage at the Romanian-American Company in Ploiești, where “the excessively irritated crowd destroyed the furniture at the company’s offices in Ploiești Teleajen.” Such violent actions spread, leading to the “decreeing [of] a state of siege for the entire oil region.”45

The dramatic situation was reflected in people’s desperate demands to be employed or to return to work at oil companies. The following are two examples of such requests: “I am the son of a widow, with 7 younger brothers. I am a graduate of the School of Arts and Crafts […]. Even though I am skilled in carpentry and wheel-craft, and I know mechanical carpentry very well and have all the legal documents […], I have not had a job for five months, and have been ignored at the factory gate for 2 weeks. I respectfully ask to be given any service that exists in the factory, and I will perform it.” Another person wrote: “I have been out of work for almost 3 months, I have run out of money and have no support other than my occupation. I have been looking for work at all of the factories in Ploiești, and could find no job.”46

This period was also marked by a tendency to dismiss employees at the slightest mistake: “The undersigned, being dismissed from my job after having worked for 21 years at this company, although I have showed nothing but honesty and hard work, as any boss and colleague of mine may confirm, I am going to be so severely punished for a reckless mistake in these difficult times. Given that I am the head of a large family, which has no other means of subsistence, please...”47

Via the voice of its president, the engineer Constantin Osiceanu, the Association of Petroleum Industrialists proposed establishing a fund to help the unemployed during the winter months. To create this fund, enterprises were asked to contribute a daily amount of 2 lei for each worker in service, and the worker himself 1 leu. The aid consisted of food that would be provided by oil companies and trade unions from this industrial sector. When publishing the information, the Moniteur du pétrole roumain deemed the decision “very fair,” and expressed the hope that both oil companies and employees would be supportive, and would “contribute to helping all those who had no work.”48

Administrators were very careful when setting wage levels, and made extremely detailed analyses of minimum needs and products indispensable for daily life. Specialized services in oil companies conducted highly detailed analyses of prices changes and increases in the cost of living, considering parameters such as food, clothing, average monthly income, etc.49 The annual assessment of each employee was also considered when setting the salary.50

When assessing an employee, a wide range of criteria was taken into account: their aptitude for the position, sense of responsibility, accuracy, hard work, energy, skill, initiative, professional knowledge, general culture, conduct towards superiors, conduct towards inferiors, conduct with equals, behaviour, and punctuality. The final grade could be either very good, good, satisfactory, or unsatisfactory. Language skills, such as writing and speaking foreign languages, were also included in the personal skills assessment grid. The following languages were considered: English, French, German, and Romanian (for foreign employees).51

Notes on an employee’s physical condition were also included, and employees were considered for more senior positions as appropriate. The observation sheet was signed by either the head of the administration department or by the head of the oil scaffolding. The latter formulated the final conclusion, which could sometimes end with very dry assessments, such as: “a mediocre manager who cannot be recommended for a higher position.”52

Nevertheless, alongside their regular activity, oil companies were concerned with improving the lives of their employees and addressing their needs. Major companies sought to build houses and homes for their managers and employees. These were sometimes concentrated in architectural ensembles (colonies), which grouped several real estate buildings located around the company (refineries). For example in 1933, Concordia provided houses for 528 of the 751 managers and workers from the oil scaffolding. For some engineers, houses were built varying from 150-170 m2 in size, while workers were provided two-bedroom apartments with a kitchen and a bathroom.53

To raise the level of satisfaction among employees and their families, salary bonuses were awarded on holidays or on the closing of yearly financial statements. For instance, Concordia gave its employees a bonus of a 13th month for Christmas and New Year’s, and another month or two of salary at the close of the annual financial statement. The bonuses awarded to senior managers whose work involved greater responsibility were higher.54 In addition to salary, bonus categories could include (for the company Astra Română) frequency, production, or footage awards for foremen etc.55

Back to topEffects of the outbreak of the Second World War on the lives of oil field workers

The third and final period in this analysis will explore the outbreak of the Second World War, during which the impoverishment of workers became extremely worrying. Specialized services within oil companies conducted analyses and made proposals for improving the well-being of their employees. One such analysis, made by the social service and presented to the administration of the Brazi Refinery near Ploiești two months after Romania entered the Second World War on 21 August 1941, emphasized the gloomy outlook. The author indicated, among other things, that: “I feel obliged to reveal the increasing dissatisfaction of personnel […], due to the excessive increase of prices, and to the fact that they are forced into malnutrition.

A lack of food has led to a permanent state of weakness, and frequent cases of anaemia with predispositions to pulmonary tuberculosis have been reported.” The document included a proposal to support families with a guaranteed minimum via a card-based rationing of food, a method that had already been adopted by other oil companies. The rising cost of products was becoming more and more alarming, and generated speculation. According to the same analysis, the average salary had increased by 60% compared to September 1939, while the increase in the price of basic foodstuffs was 600%.

Another document also highlighted the state of poverty in which most of the employees lived. Due to the increasing cost of shoes and leather, “workers come to work with wooden planks fastened with straps to their feet.” It was therefore proposed that footwear be purchased and distributed to workers in the enterprise, thereby avoiding the risk of employees not coming to work during the winter.56

In December 1941, oil companies introduced cards that were distributed to employees for a certain fee, and that ensured the distribution of bread, corn, meat, sugar, vegetables (potatoes, onions, beans), jam, firewood, etc.

War was undoubtedly a major burden on the entire economy, and the launch of a national loan to bear it meant a substantial contribution from the oil industry.57 Employees had to make mandatory contributions in an amount consistent with their income.58 There were also charitable actions in which oil workers felt obliged to show solidarity with those in great distress. For example, managers from a refinery in Ploiești offered one day’s salary for the wounded, a gesture that was certainly not unique. Oil companies became involved in supporting and creating camps for refugees,59 in helping the wounded, sending presents to soldiers at the front, etc.

Social problems were compounded by those arising from the great earthquake of November 1940. Oil companies were involved in the relief effort by covering 40% of the expenses needed to rebuild employee homes that were the most affected.

Despite material difficulties, oil industry employees were involved in various cultural and educational programmes during the period. Some adhered to the spirit of the time, namely to cultivate patriotism and to mobilize for the war effort. There were significant festivities on holidays such as January 24, the day of the Union of the Romanian Principalities in 1859, and December 1, the Day of the Union of all Romanians in 1918. At the presentation of the play “I Order You to Cross the Prut River”, a title based on the order that the Romanian head of state gave when declaring war on the USSR, oil industry employees were invited to participate along with members of their family.60

Focus on medical matters and health care provides a better understanding of the generally complex context of the time. Oil companies set up medical dispensaries directly at oil sites, and in 1941 central authorities intervened to demand that all oil companies with 1,000 employees or more set up dispensaries with at least two rooms and all of the necessary medical equipment.61 In 1940, a Social Fund was created within the Ministry of Economy, which allowed companies to send hundreds of employees to spas each year to restore their health. The employees were provided financial support for rail transportation and accomodations at the resort.62

To conclude, the situation of oil industry employees was fairly complex and diverse, ranging from severe material shortage to financial contribution in support of the war effort and a social life adapted to the time.

Back to topConclusion

This paper has covered a wide range of social issues relating to employees in the Romanian oil industry during the interwar period. Each of the three identified periods were presented, as were their distinctive features. Firstly, due to a trend toward greater democracy that emerged after the First World War, state authorities initiated a vast legislative process to establish a social protection policy, which was to be achieved either by granting universally recognized rights, or by setting up institutions to implement social protection mechanisms.

At the level of the oil industry, the interests of employees were generically represented by the Association of Petroleum Industrialists of Romania. However, the best representation was provided for the interests of employees with higher education, board managers, and employers within oil companies, whereas the interests of employers with secondary education, skilled workers, and unskilled workers were not a major preoccupation. This explains why the above-mentioned association often did not embrace and even rejected proposals in favour of its many ordinary employees. The association welcomed democratic principles, but wanted to apply them according to the logic and interests of employers. For all that, social protection for oil industry employees was established via a slow but steady process of improvement.

The global crisis between 1929 and 1933 was a dramatic time, characterized by negative economic effects on the oil industry, and hence on its employees. Personal hardship sometimes led to riots, which spread to the entire oil region. The criteria for paying salaries involved extremely detailed monitoring of employees.

After the general economic easing brought by the years 1934-1938, the Second World War represented another stage with multiple constraints of an economic, financial, and social nature. Most oil industry employees ate and dressed poorly, and, even had to provide financial support for the war. The situation was of course similar across the national economy, although the standard of living of oil industry employees was higher than in other industries or in agriculture. During the entire interwar period, oil industry employees formed a professional, economic, and social elite within Romanian society, with higher training and qualifications.

- 1. This paper is a revised and updated version of the presentation I gave at the conference entitled “Hydrocarbons and societies: labour, social relations and industrial culture in the 19th and 20th centuries” which was organized by Total, the Comité d’Histoire de l’électricité et de l’énergie, UMR SIRICE, Sorbonne Université, and EOGAN, Paris on 5 February 2021. (See Gheorghe Calcan, În universul petrolului românesc/ In the Universe of the Romanian Oil Industry (Cluj-Napoca: Mega Publishing House, 2022), 171-188. I would like to thank the reviewers from The Journal of Energy History for their helpful suggestions.

- 2. Gheorghe Ivănuş et al., The Petroleum and Gas History of Romania (Bucharest: AGIR Publishing House, 2017), 77 – 85. See also Constantin M. Boncu, Contribuții la istoria petrolului românesc/ Contributions to the History of the Romanian Oil Industry, (Bucharest: Academiei Publishing House, 1971), 98-102; Gheorghe Calcan, “160 de ani de industrie petrolieră românească/ 160 Years of Romanian Petroleum Industry”, in Mihail Minescu et al. (coordinators), 2017 – Prahova Capitală Mondială a Petrolului. 160 de ani de industrie petrolieră în România. 50 de ani de învățământ superior la Ploiești/ World Capital of Petroleum, 1967 – 2017: 160 Years of Romanian Petroleum Industry, 50 Years of Superior Education at Ploiesti (Ploiești: Petroleum-Gas University Press of Ploieşti, 2017), 21- 35.

- 3. Gh. Buzatu, O istorie a petrolului românesc/ A History of the Romanian Oil Industry (Bucharest: Enciclopedică Publishing House, 1998), 12, 255.

- 4. “L’exportation des produits pétrolifères de la Roumanie pendant l’année 1936”/ “The Export of the Romanian Oil Products starting with 1936”, Moniteur du pétrole roumain (M.P.R.), no 6, 1937, 372; Gh. Calcan, Industria petrolieră din România în perioada interbelică. Confruntări şi opţiuni în cercurile de specialişti/ Oil Industry in Romania in the Inter-war Period. Confrontations and Options in the Specialists Circles (Bucharest: Tehnică Publishing House, 1997), 152.

- 5. For the First World War, see Gheorghe Calcan, “La destruction de l’industrie pétrolière roumaine pendant la Première Guerre mondiale”, in Alain Beltran (ed), Le pétrole et la guerre, Oil and War, Conference organized by the CNRS and the Total Company, 11-12 February, 2010, Paris (Brussels: P. I. E., Peter Lang, 2012), 21-36, and for the Second World War, see Gavriil Preda, Importanța strategică a petrolului românesc 1939-1947/ The Strategic Importance of the Romanian Oil (Ploiesti: PrintEuro Publishing House, 2001).

- 6. For the policy in connection with the Romanian oil industry, as well as the relation between Romanian and foreign capital, see: Gheorghe Buzatu, România şi trusturile petroliere internaţionale până la 1929/ Romania and the International Oil Trusts prior to 1929 (Iași: Junimea Publishing House, 1981); Gh. Buzatu, A History of the Romanian Oil, vol. I, (Bucharest: Mica Valahie Publishing House, 2004), 325-434; Gheorghe Calcan, “Concerning the Nationalisation of the Rumanian Oil Industry. The Mining Law of 1924 and its Rejoinders of 1929 and 1937”, in Alain Beltran (ed), Oil Producing Countries and Oils Companies. From the Nineteenth Century to the Twenty-First Century, Conference organized by CNRS and the Total Company, 18-19 September 2006, Paris (Brussels: P. I. E., Peter Lang, 2011), 245-265; Gheorghe Stănescu, Gabriel Octavian Nicolae, Mihail Minescu, Petrolul Românesc – 160 de ani de istorie ilustrată/ Romanian Oil. 160 years of history by pictures (Boldaș Publishing House, 2017), 176.

- 7. Gh. Ivănuş, et al., Industria petrolului în România/ Oil Industry in Romania (Bucharest: AGIR Publishing House, 2004), 469 – 470.

- 8. Gheorghe Calcan, “160 lat rumunskiego przemyslu naftowego (1857-2017)”, Wiek Nafty, vol. XXVII, no 1 (100) 2018, 24-37.

- 9. See Calcan, În universul petrolului românesc/ In the Universe of the Romanian Oil Industry, 78-85 (cf. note 1).

- 10. Calcan, Industria petrolieră din România/ Oil Industry from Romania, 232 (cf. note 4).

- 11. Ion Agrigoroaiei, România interbelică, vol. I/ The Interwar Romania, vol. I, (Iași: “Alexandru Ioan Cuza” University Publishing House, 2001), 90-110.

- 12. Ioan Scurtu (coord), Istoria românilor, vol. VIII, România întregită (1918-1940)/ The History of the Romanians, vol III, Reunited Romania (1918-1940 (Bucharest: Enciclopedică Publishing House, 2003), 183.

- 13. Agrigoroaiei, România interbelică/ The Interwar Romania, 242 (cf. note 11); “120 de ani de la intrarea în vigoare a Legii repausului în zilele de duminică şi sărbători”/ “120 Years since the Adoption of the Law of Rest on Sundays and Legal Holidays”, http://stiri.tvr.ro/120-de-ani-de-la-intrarea-in-vigoare-a-legii-repaus…, (accessed 18/03/2020).

- 14. See Calcan, Industria petrolieră din România/ Oil Industry from Romania, 35, 38, 62-64, 77-78, 108 (cf. note 4).

- 15. “Legea repausului duminical și industria de petrol”/ “The Law of Sunday Rest and Oil Industry”, M.P.R., no 13, 1925, 1128-1129.

- 16. Tudor Rățoi, Din modernizarea României interbelice. Legislația socială a muncii/ From the Modernization of the Interwar Romania. Social labour Legislation (Iași: Antheros Publishing House, 1998), 117-120.

- 17. Ion Țuțuianu, “Camerele de muncă – etapă în dezvoltarea Dreptului muncii în România”/ “Chambers of Labour: Stage in the Development of the Labour Law in Romania”, Revista Națională de Drept/ National Law Journal, no 12, 2012, 43-45, (https://ibn.idsi.md/sites/default/files/imag_file/43_45_Camerele%20de%2… (accessed 20/11/2022).

- 18. Rățoi, Din modernizarea României interbelice/ From the Modernization of the Interwar Romania, 61-62 (cf. note 15).

- 19. “Industria de petrol și Camerele de Muncă”/ “Oil Industry and Chambers of Labour”, M.P.R., no 13, 1925, 1126-1128.

- 20. Id.

- 21. Id.

- 22. Rățoi, Din modernizarea României interbelice/ From the Modernization of the Interwar Romania, 63-64 (cf. note 15).

- 23. Țuțuianu, “Camerele de muncă”/ “Chambers of Labour”, 43 (cf. note 16).

- 24. See, for example, Andrei Rădulescu, Unificarea legislativă/ Legislative Unification (Bucharest: Cultura Naţională Publishing House, 1927); C. Hamangiu, Unificarea legislativă a României. Proiect de lege şi expunere de motive întocmit de C. Hamangiu, ministrul Justiţiei/ The Legislative Unification of Romania. Draft Law and Statement of Reasons drawn up by C. Hamangiu, Minister of Justice (Bucharest: Imprimeria Naţională Publishing House, 1931); Gh. Iancu, “Unificarea legislativă. Sistemul administrativ al României (1919 – 1939)”/ “Legislative Unification. The Administrative System of Romania (1919 – 1939)”, in Vasile Puşcaş, Vasile Vesa (dir.), Dezvoltare şi modernizare în România interbelică, 1919 – 1939/ Development and modernization in interwar Romania, 1919 – 1939 (Bucharest: Politică Publishing House, 1988), 39 – 67; Gheorghe Calcan, The Administrative Unification of Greater Romania. Integrating Bessarabia, Bukovina and Transylvania into the Romanian Government Structures, 1918-1925 (Saarbrücken: Universitaires Européennes Publishing House, 2017).

- 25. Agrigoroaiei, România interbelică/ The Interwar Romania, 237-238, 243 (cf. note 11).

- 26. See, for example, Morgane Labbé, “Social movement and economic statistics in interwar Poland: building an alternative expert on the condition of the working class”, in Fabio Giomi et al., (dir.), Public and Private Welfare in Modern Europe. Productive Entanglements (London and New Iork: Routlege, Taylor & Francis Group, 2022), 79, 83 https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/oa-edit/10.4324/9781003275459/publi… (accessed 30/11/2022).

- 27. Agrigoroaiei, România interbelică/ The Interwar Romania, 132-133 (cf. note 11).

- 28. Ioan Scurtu, “Viața politică din România în anii 1918-1923”/ “Political life in Romania in the years 1918-1923", in Ioan Scurtu (dir.), Marea Unire din 1918 în context european/ The Great Union of 1918 in a European context (Bucharest: Enciclopedică & Academiei Române Publishing House, 2003), 291-346.

- 29. See Rățoi, Din modernizarea României interbelice/ From the Modernization of Interwar Romania, (cf. note 15; Agrigoroaiei, România interbelică/ Interwar Romania, 238-246 (cf. note 11).

- 30. The process of establishing such ministries was part of a wider trend, specific to the changes brought about by the Fisrt World War. For example, in Poland the Ministry of Social Protection was established in 1918. Labbé, “Social movement and economic statistisc”, 79 (cf. note 26).

- 31. “În chestia proiectului de lege al asigurărilor sociale”/ “With Respect to the Draft Law of Social Security”, M.P.R., no 5, 1926, 448-450.

- 32. Id.

- 33. Collection Moniteur du pétrole roumain (1900 – 1947) includes numerous articles on the taxes applied in the petroleum industry. See, among others, “Două intervențiuni”/ “Two Interventions”, M.P.R, no 22, 1924, 1770 – 1773; “Industria de petrol la d. ministru al Industriei”/ “Oil Industry and Its Ministry”, M.P.R., no 22, 1924, 1809; “Asociația Industriașilor de Petrol din România și reducerea taxelor de export”/ “The Association of Oil Industrialists from Romania and the Reduction of Export Taxes”, M.P.R., no 1, 1925, 45 – 59; “Reducerea taxelor de export”/ “The Reduction of Export Taxes”, M.P.R., no 15, 1926, 1573 etc.

- 34. “O întrunire a inginerilor din industria de petrol”/ “A Meeting of Engineers in the Oil Industry”, M.P.R. no 5, 1926, 455.

- 35. “Proiectul de lege al asigurărilor sociale”/ “Draft of the Social Insurance Law”, M.P.R., no 14, 1926, 1471.

- 36. Id. According to statistics, between 1923 and 1929 the number of work accidents doubled in the extractive industry. In 1929, 1,100 accidents were registered, of which 64 were fatal, and in 1929, the number of accidents reached 2,329, of which 109 were fatal. (Dan Ovidiu Pintilie, Istoricul societății “Concordia”, 1907-1948/ The History of “Concordia” Society (Ploiești: Petroleum-Gas University Press of Ploiești, 2007), 63-64. For details on uncontrolled wells eruptions and the accidents they caused, see Constantin Șerban, Astra Română, societate de prestigiu a petrolului românesc din perioada interbelică/Astra Română: A Prestigious Romanian Oil Company from the Interwar period (Association of the Society of Petroleum and Gas Engineers Publishing House, 2014), 218-244.

- 37. Rățoi, Din modernizarea României interbelice/ From the Modernization of Interwar Romania, 146-151 (cf. note 15).

- 38. Ibid., 146, 152.

- 39. “Asigurările sociale și salariații din industria minieră”/ “Social Insurance and the Employees in the Mining Industry”, M.P.R., no 7, 1936, 541 – 542.

- 40. Id.

- 41. Rățoi, Din modernizarea României interbelice/ From the Modernization of Interwar Romania, 154-155 (cf. note 15).

- 42. Ibid., 409-420.

- 43. For a comparative perspective of the process of social protection in Europe, see: Giomi et al., (dir.), Public and Private Welfare in Modern Europe (cf. note 26); Gisela Hauss, Dagmar Schulte (eds), Amid Social Contradictions. Towards a History of Social Work in Europe (Michigan: Barbara Budrich Publishers, Opladen & Farmington Hills, 2009), http://www.blickinsbuch.de/item/fb1c12168add3a5f2f7e9ecdc09f37c5 (accessed 25/11/2022).

- 44. Calcan, Industria petrolieră din România/ Oil Industry from Romania, 115-116 (cf. note 4).

- 45. “Conflicte de muncă în industria petrolieră”/ “Work Conflicts in the Oil Industry”, M.P.R, no 4, 1933, 195 -196.

- 46. Arhivele Naționale ale României, Direcția Județeană Prahova, Fond Astra Română (ANR)/ National Archives of Romania. Prahova County Directorate, Astra Română Fund, vol. 9,1931, 9, 28.

- 47. Ibid., p. 29.

- 48. “Pentru șomerii din industria petrolieră”/ “For the Unemployed in the Oil Industry”, M.P.R., no 24, 1930, 1396.

- 49. ANR, vol . 10, 1931 - 1932 (cf. note 46).

- 50. Calcan, Industria petrolieră din România/ Oil Industry from Romania, 177 (cf. note 4).

- 51. ANR, vol .8, 1936-1938, 9 (cf. note 46).

- 52. Calcan, Industria petrolieră din România/ Oil Industry from Romania, 177 (cf. note 4).

- 53. Pintilie, Istoricul societății “Concordia”/ The History of the Concordia Company, 64 (cf. note 36).

- 54. Ibid., 66.

- 55. Constantin Dobrescu, Istoricul societății “Astra Română”/ The History of the Astra Română Company, 1880-1948 (Cerașu: Scrisul Prahovean Publishing House, 2002), 90-91.

- 56. ANR, Fond Societatea Creditul Minier/ Mining Credit Society Fund, Bucharest, Brazi Refinery, vol. 22, 1941, 25-26, 77-80, 89; 1940, 44 (cf. note 46); ANR, Ploiești Refinery, vol. 11, 1940–1942, 26, 83, 172,192–283 (cf. note 46); Calcan, Industria petrolieră din România/ Oil Industry from Romania, 246 (cf. note 4).

- 57. “Subscrierile societăților petroliere la Împrumutul Reîntregirii”/ “The Subscriptions of the Oil Companies to the Reunion Loan”, M.P.R., no 24, 1941, 965.

- 58. Calcan, Industria petrolieră din România/ Oil Industry from Romania, 245 (cf. note 4).

- 59. Dobrescu, Istoricul societății “Astra Română”/ The History of the Astra Română Company, 98 (cf. note 55).

- 60. Ibid., 246.

- 61. Pintilie, Istoricul societății “Concordia”/ The History of the Concordia Company, 67 (cf. note 36).

- 62. Ibid., 66-67.

National Archives of Romania, Prahova County Directorate, Astra Română Fund, vol. 8-10,1931-1938.

National Archives of Romania, Prahova County Directorate, Astra Română Fund, Ploiești Refinery, vol. 11, 1940 – 1942.

National Archives of Romania, Prahova County Directorate, Creditul Minier Society Fund, Bucharest, Brazi Refinery, vol. 22, 1941.

Agrigoroaiei Ion, România interbelică, vol. I/ The Interwar Romania, vol. I (Iași: “Alexandru Ioan Cuza” University Publishing House, 2001).

Agrigoroaiei Ion, “Asigurările sociale și salariații din industria minieră”/ “Social Security and Mining Employees”, Moniteur du pétrole roumain, no 7, 1936, 541 – 542.

Agrigoroaiei Ion, “Asociația Industriașilor de Petrol din România și reducerea taxelor de export”/ “The Association of Oil Industrialists from Romania and the Reduction of Export Taxes”, Moniteur du pétrole roumain, no 1, 1925, 45 – 59.

Boncu Constantin M., Contribuții la istoria petrolului românesc/ Constributions to the History of the Romanian Oil Industry (Bucharest: Academiei Publishing House, 1971).

Buzatu Gheorghe, România şi trusturile petroliere internaţionale până la 1929/ Romania and the International Oil Trusts prior to 1929 (Iași: Junimea Publishing House, 1981).

Buzatu Gheorghe, O istorie a petrolului românesc/ A History of the Romanian Oil Industry (Bucharest: Enciclopedică Publishing House, 1998).

Buzatu Gheorghe, A History of the Romanian Oil, vol. I, (Bucharest: Mica Valahie Publishing House, 2004).

Calcan Gheorghe, Industria petrolieră din România în perioada interbelică. Confruntări şi opţiuni în cercurile de specialişti/ The Oil Industry in Romania in the Interwar period: Confrontations and Options in the Circles of Specialists (Bucharest: Technică Publishing House, 1997).

Calcan Gheorghe, “Concerning the Nationalisation of the Rumanian Oil Industry. The Mining Law of 1924 and its Rejoinders of 1929 and 1937”, in Beltran Alain (ed), Oil Producing Countries and Oils Companies. From the Nineteenth Century to the Twenty-First Century (Brussels: P. I. E., Peter Lang, 2011), 245-265.

Calcan Gheorghe, “La destruction de l’industrie pétrolière roumaine pendant la Première Guerre mondiale”, in Beltran Alain (ed), Le pétrole et la guerre, Oil and War (Brussels: P. I. E., Peter Lang, 2012), 21-36.

Calcan Gheorghe, “160 de ani de industrie petrolieră românească/ 160 Years of Romanian Petroleum Industry”, in Minescu Mihail, Cursaru Diana Luciana, Albulescu Mihai Adrian, Neagu Ionela, (coordinators), 2017 – Prahova Capitală Mondială a Petrolului/ World Capital of Petroleum, 1967 – 2017, 160 de ani de industrie petrolieră în România. 50 de ani de învățământ superior la Ploiești (Ploiești: Petroleum-Gas University Press of Ploieşti, 2017), 21- 35.

Calcan Gheorghe, The Administrative Unification of Greater Romania. Integrating Bessarabia, Bukovina and Transylvania into the Romanian Government Structures, 1918-1925 (Saarbrücken: Universitaires Européennes Publishing House, 2017).

Calcan Gheorghe, “160 lat rumunskiego przemyslu naftowego (1857-2017)”, Wiek Nafty, vol. XXVII, no 1 (100) 2018, 24-37.

Calcan Gheorghe, În universul petrolului românesc/ In the Universe of the Romanian Oil Industry (Cluj-Napoca: Mega Publishing House, 2022).

Calcan Gheorghe, “Conflicte de muncă în industria petrolieră”/ “Work Conflicts in the Oil Industry”, Moniteur du pétrole roumain, no 4, 1933, 195 -196.

Dobrescu Constantin, Istoricul societății “Astra Română”/ The History of “Astra Română” Society, 1880-1948 (Cerașu: Scrisul Prahovean Publishing House, 2002).

Dobrescu Constantin, “Două intervențiuni”/ “Two Interventions”, Moniteur du pétrole roumain, no 22, 1924, 1770 – 1773.

Giomi Fabio, Keren Célia, Labbé Morgane, (dir.), Public and Private Welfare in Modern Europe. Productive Entanglements (London and New Iork: Routlege, Taylor & Francis Group, 2022).

Hamangiu C., Unificarea legislativă a României. Proiect de lege şi expunere de motive întocmit de C. Hamangiu, ministrul Justiţiei/ The Legislative Unification of Romania. Draft Law and Statement of Reasons Drawn up by C. Hamangiu, Minister of Justice (Bucharest: Imprimeria Naţională Publishing House, 1931).

Hauss Gisela, Schulte Dagmar (eds), Amid Social Contradictions: Towards a History of Social Work in Europe (Michigan: Barbara Budrich Publishers, Opladen & Farmington Hills, 2009).

Iancu, Gh., “Unificarea legislativă. Sistemul administrativ al României (1919 – 1939)”/ “Legislative unification. The Administrative System of Romania (1919 – 1939)”, in Vasile Puşcaş, Vasile Vesa (dir.), Dezvoltare şi modernizare în România interbelică, 1919 – 1939/ Development and Modernization in Interwar Romania, 1919 – 1939 (Bucharest: Politică Publishing House, 1988).

Iancu, Gh., “Industria de petrol la d. ministru al Industriei”/ “Oil Industry in the View of Ministry of Industry, Moniteur du pétrole roumain, no 22, 1924, 1809.

Iancu, Gh., “Industria de petrol și Camerele de Muncă”/ “Oil Industry and Chambers of Labour” Moniteur du pétrole roumain, no 13, 1925, 1126-1128.

Iancu, Gh., “În chestia proiectului de lege al asigurărilor sociale”/ “On the Social Insurance Draft Law” Moniteur du pétrole roumain”, no 5, 1926, 448-450.

Ivănuş Gheorghe, Antonescu Niculae Napoleon, Ştefănescu Ion Ștefan, Coloja Mihai Pascu, Mocuța Ștefan-Traian, Stirimin Ştefan, The Petroleum and Gas History of Romania (Bucharest: AGIR Publishing House, 2017).

Ivănuş Gh., Ştefănescu, I., Mocuţa, Şt.-Tr., Stirimin, Şt. N., Coloja, M. P., Industria petrolului în România/ Oil Industry in Romania (Bucharest: AGIR Publishing House, 2004).

Labbé Morganen, “Social Movement and Economic Statistisc in Interwar Poland: Building an Alternative Expert on the Condition of the Working Class”, in Fabio Giomi, Célia Keren, Morgane Labbé (dir.), Public and Private Welfare in Modern Europe. Productive Entanglements (London and New Iork: Routlege, Taylor & Francis Group, 2022), 79-106.

Labbé Morganen, “Legea repausului duminical și industria de petrol”/ “The Law of Sunday Rest and Oil Industry” Moniteur du pétrole roumain, no 13, 1925, 1128-1129.

Labbé Morganen, “L’exportation des produits pétrolifères de la Roumanie pendant l’année 1936”/ “The Export of the Romanian Oil Products starting from 1936”, Moniteur du pétrole roumain, no 6, 1937, 372.

Labbé Morganen, “O întrunire a inginerilor din industria de petrol”/ “A Reunion of Oil Industry Engineers” Moniteur du pétrole roumain, no 5, 1926, 455.

Labbé Morganen, “Pentru șomerii din industria petrolieră”/ “For the Unemployed in the Oil Industry” Moniteur du pétrole roumain, no 24, 1930, 1396.

Labbé Morganen, Pintilie Dan Ovidiu, Istoricul societății “Concordia”/ The History of “Concordia” Society, 1907-1948 (Ploiești: Petroleum-Gas University Press of Ploiești, 2007).

Preda Gavriil, Importanța strategică a petrolului românesc 1939-1947/ The Strategic Importance of the Romanian Oil 1939-1947 (Ploiești: PrintEuro Publishing House, 2001).

Preda Gavriil, “Proiectul de lege al asigurărilor sociale”/ “The Draft Law of Social Insurance” Moniteur du pétrole roumain, no 14, 1926, 1471.

Rădulescu Andrei, Unificarea legislativă/ Legislative Unification (Bucharest: Cultura Naţională Publishing House, 1927).

Rățoi Tudor, Din modernizarea României interbelice. Legislația socială a muncii/ From the Modernization of the Interwar Romania. Social labour Legislation (Iași: Antheros Publishing House, 1998).

Rățoi Tudor, “Reducerea taxelor de export”/ “Reducing Export Taxes”, Moniteur du pétrole roumain, no 15, 1926, 1573.

Scurtu Ioan (dir.), Istoria românilor, vol. VIII, România întregită (1918-1940)/ The History of the Romanians, vol. VIII, Reunited Romania (1918-1940) (Bucharest: Enciclopedică Publishing House, 2003).

Scurtu Ioan, “Viața politică din România în anii 1918-1923”/ “Political Life in Romania in the years 1918-1923”, in Ioan Scurtu (dir.), Marea Unire din 1918 în context european/ The Great Union of 1918 in the European context (Bucharest: Enciclopedică & Academiei Române Publishing House, 2003), 291-346.

Scurtu Ioan, “Statistica personalului din industria petrolieră”/ “The Statistics of the Personnel in the Oil Industry” Moniteur du pétrole roumain, no 20, 1939, 1297- 1301.

Stănescu Gheorghe, Nicolae Gabriel Octavian, Minescu Mihail, Petrolul românesc – 160 de ani de istorie ilustrată/ The Romanian Oil: 160 Years of History by Pictures (Boldaș Publishing House, 2017).

Stănescu Gheorghe, Nicolae Gabriel Octavian, Minescu Mihail, “Subscrierile societăților petroliere la Împrumutul Reîntregirii”/ “The Subscriptions of the Oil Companies to the Reunion Loan”, Moniteur du pétrole roumain, no 24, 1941, 965.

Șerban Constantin, Astra Română, societate de prestigiu a petrolului românesc din perioada interbelică/ Astra Română, A Prestigious Romanian Oil Company from the Interwar Period (Association of the Society of Petroleum and Gas Engineers Publishing House, 2014).

Țuțuianu Ion, “Camerele de muncă – etapă în dezvoltarea Dreptului muncii în România”/ “Chambers of Labour: a Stage in Implementing the Labour Law in Romania”, in Revista Națională de Drept/ Law National Journal, no 12, 2012, 43-45, https://ibn.idsi.md/sites/default/files/imag_file/43_45_Camerele%20de%2…, (accessed 19/03/2022).

Țuțuianu Ion, “120 de ani de la intrarea în vigoare a Legii repausului în zilele de duminică şi sărbători”/ “120 Years since the Adoption of the Law of Rest on Sundays and Legal Holidays”, http://stiri.tvr.ro/120-de-ani-de-la-intrarea-in-vigoare-a-legii-repaus…, (accessed 18/03/2022).