Manual and Electrical Energies in the Visualisation of “Electrical Calcutta”, c. 1890-1925

Marie Sklodowska-Curie Postdoctoral Fellow, University of Stavanger

animesh.chatterjee[at]uis.no

@electricpunkah

This article owes much to support from the European Research Council (ERC) and Leeds Trinity University. I am indebted to colleagues in the ERC project “A Global History of Technology” (Project No. 742631) at Technische Universität Darmstadt, and the Electrical History Research Group based at the University of Leeds, especially Karen Sayer, Graeme Gooday and Mikael Hård, who have all been very generous with their time and feedback. The final stages of writing this article were supported by the Marie Sklodowska-Curie Postdoctoral Fellowship (Project No. 101061421) at the University of Stavanger. I also thank the archivists at the National Library, and the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences in Calcutta, the British Library in London and Boston Spa, and the Institution of Engineering and Technology in London. Finally, my thanks to the anonymous reviewers, Daniel Perez Zapico, and the journal editor Léonard Laborie for their insightful comments and suggestions.

Through examinations of domestic servants in electrical advertisements and writings this article looks at the imaginations and realities of visions of an “Electrical Calcutta” at the turn of the twentieth century. It argues that the diverse conceptions of an “Electrical Calcutta” were intimately linked to not just the technological and mechanical benefits of electrical technologies, but also the centrality of servants to societal notions of morality, class and social hierarchy, and cultures and discourses of human bodies, labour and energy within the domestic sphere.

Introduction

Electrical Calcutta is still in embryo; indeed for that matter so is electrical India. […] the coolie whose duty it is to pull the punkah o’nights, or see that the cocoanut-oil lamp is properly trimmed, or to take messages with somewhat more rapidity than an A.D.T. boy displays — slowly but surely this individual is working out his own condemnation by his infernal stupidity and laziness, and electrical appliances are taking his place.1

Writing a little more than a year after Calcutta Electric Supply Corporation’s power plant began its operations in April 1899, R. W. Ashcroft, a member of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, preached his beliefs in the foreseeable and eventual growth of the nascent electrical enterprise in Calcutta. Although the successful installation and operation of the power plant not far from the colonial centre of Calcutta marked the moment when a new electrical future became possible, for Ashcroft the future of an “electrical Calcutta” depended on educating future consumers to the conveniences and efficiencies of electricity for the most ordinary everyday purposes. While residents of Calcutta still used technologies like hand-pulled punkahs (cloth or feather fans that were either hand-held or attached to frames suspended from ceilings) or oil and gas lamps, Ashcroft envisioned a generally favourable acceptance of electric supply and appliances in public and domestic spheres. Calcutta Electric Supply Corporation, he predicted, “will pay handsome dividends, at least from that department appertaining to supplying power for electric fans.”2 Yet ultimately, the success of the electrical enterprise depended on replacing servants, especially those employed to pull punkahs or trim oil lamps, with electrical power and technologies. Too often, he lamented, servants, and their energies and labour were unreliable, inefficient, unacceptable and far removed the conveniences that defined a hygienic, disciplined and modern domestic life. Ashcroft insisted that electrical technologies were far more convenient and efficient and, importantly, did not require constant interventions from householders to keep them working. Servants such as punkah pullers or coolies, he argued, while employed to keep their employers comfortable, were known to fall asleep, resulting in admonitions or even violence: “in India, a boot-jack is used nocturnally to create activity rather than to suppress it; and, even if your aim is good, the punkah coolie will be off to sleep again in the next 15 minutes.”3 Evidently, Ashcroft surmised, householders in Calcutta would soon replace the coolies under their employ with “Western methods of breeze-manufacturing” through electric fans.4

As Ashcroft’s commentary illustrates, the possibilities of an “electrical Calcutta” were entangled with new ways of approaching questions of efficiency, servants’ bodies and labour, and violence against domestic servants. Starting in the early 1890s, traders of electrical appliances and electrical experts were responding similarly to domestic servants in their progressive advertising projects and commentaries on the outlooks of the nascent electrical enterprise in Calcutta. Such efforts were mainly directed towards elite and middle-class British and Bengali residents of Calcutta who also primarily employed servants in their households. Changing patterns of elite and middle-class consumption were also integral to the growing commercial electrical market, including both well-established organisations such as the General Electric Company and local traders, which used advertising and article spaces in newspapers and periodicals to promote domestic electrical devices in innovative ways. The electrical industry was not the first, however, to explore the commercial possibilities of shaping discourses with the elite and middle classes in mind. Recent studies of consumption in late-nineteenth and early twentieth century India have also highlighted the ways in which advertisements and writings that appeared in print and other media shaped, and were shaped by, the burgeoning British and Indian elite and middle-class consumer society. They argue that advertisers modified their themes around the buying powers and anxieties of the elite and middle classes.5

This article concentrates on particular moments in electrical writings and advertisements which registered or responded to the presence of servants in domestic and public spaces in colonial Calcutta. By exploring these moments and looking specifically for servants in visualisations of “electrical Calcutta”, this article reveals the ways in which representations, meanings, actions and politics of employer-servant relationships, class and social relations and domestic labour were irretrievably bound up with discussions about energy sources and transitions. On first glance, this article might seem to make arguments that scholars of energy and electrical histories are familiar with. For instance, an examination of the political and ethical stakes involved in promoters of domestic electrical technologies in late-nineteenth and early twentieth century Britain building their discourses around the difficulties faced by a bourgeois society failing to recruit and discipline servants is central to Graeme Gooday’s theme of “domestication” of electricity.6 A study of the ways in which advertisers and promoters both deployed and contributed to racial and class politics, and Mexicans’ sense of self by selling the idea of an “electric life” through the “so-called maid problem” can be seen in Diana J. Montaño’s Electrifying Mexico.7 Both Gooday and Montaño show that the visibility and presence of servants in the marketing of electrical futures in Britain and Mexico, respectively, went beyond simply the technological and practical values of electricity.8 Indeed, the ways in which elite and middle-class societies conceptualised the shortage of servants and the decline of domestic service were central to representations of domestic electrification during its early years. Yet, in the case of late-nineteenth and early twentieth century Calcutta (and India), electrical promoters needed to place their arguments in a social and cultural environment that was witnessing a phenomenal increase in domestic service and the number of domestic servants.9

Social histories have documented the ways in which servants’ energy-intensive labour was increasingly embedded in their British and Bengali middle-class gentlemanly, or bhadralok, employers’ notions of domestic health, well-being and social identities. Historians have elaborated a rich picture of British and bhadralok investment in the moral, social and political implications of employing native servants. In British discussions, the native servant figured as a surrogate for the colonised population, occupying a symbolic position in affirming British residents’ positions as rulers in the colonised world.10 Colonial notions of empire, order and domesticity, therefore, converged in the “Anglo-Indian” interior, offering comparisons with the administration of a colonial empire.11 For the literate bhadralok intelligentsia, native servants and the urban poor were understood and interpreted from within reformist discourses that centred around the creation of an “autonomous” and “spiritual” domain of the “home”.12 As the rich and growing literature on employer-servant relationships in the context of colonial India has shown, the growth of the Indian middle class, with a focus on gender and class hierarchies within the home, came with pressures to consume and manage domestic labour — especially that of women and servants — in a way that reflected the construction of new ideas of domesticity, self-identity and respectability. Domestic servants were central to the creation of the moral universe around the home and family. Middle-class hegemony and paternalism was usually established and maintained through analysing the housewife’s character and status in terms of the discipline and behaviours of the servants under her charge. Any acts of subordination or dishonesty committed by servants were considered to be reflections of the failures of the employers — especially the housewife — to maintain cultural values and morality within their households.13

In this article, I examine the ways in which both British and Indian electrical marketers understood British and bhadralok pursuits of identities based on definitions and differences of class and anxieties about domestic morality. I show how the place of servants in employers’ definitions of their self and class identities proliferated into diverse approaches to promote transitions from the manual labour of servants and the seemingly problematic consumption of oil and gas to electrical technologies. In doing so, this article pursues two related lines of inquiry. The first is suggested in electrical promoters’ recognition of the ubiquity and importance of employing servants and domestic service in British and bhadralok households. Within that context, they adapted, reinforced and even exacerbated the symbolic language associated with managing and shaping domestic labour and energy by equating the use of electrical technologies alongside domestic servants with visions of efficient, orderly and moral domestic spaces.

In the first section, I will examine advertisements for, and writings on electric bells and lighting that highlighted the physical limitations of human bodies and behaviours in providing efficient domestic service, and mapped human virtues of discipline and morality on to electrical technologies. Promoters and advertisers foreground electric bells and lighting as both means of economising employers’ mental and physical energies, and as tools that could appropriately shape the manner in which servants functioned and behaved in domestic spaces, ensuring that servants were productive, honest and disciplined in their service. New electrical technologies were, therefore, not simply labour-saving, but also centred around labour management.

The second line of inquiry addresses promoters’ adoption of racist and classist conceptions of domestic servants, their bodies and labour as standards by which to present the advantage of electrical technologies. Servants and their bodies were compared to machines that required constant interventions from employers to keep them working efficiently. As we have seen in Ashcroft’s article discussed in the opening of this study, the punkah-wallah encapsulated these concerns: the punkah required constant inputs from the punkah-wallah in order to function efficiently, but the punkah-wallah’s efficiency was ultimately predicated on the employer’s capacity to keep the punkah-wallah infinitely productive.

In the second section of this article, I examine discussions on the removal of punkah-wallahs and the electrification of punkah-pulling systems, especially against the colonial and nationalist politics surrounding the tragically commonplace violence on punkah-wallahs at the hands of their European and British employers. Here, I build upon recent studies in the history of labour in colonial India that have evinced a new and welcome focus to the politics surrounding the profession of punkah-pulling. I pursue some of the implications of Jordanna Bailkin’s examination of the medico-legal, racist and bodily politics engendered in cases of violence by looking at punkah-wallahs as both victims of racial violence and expendable components of ventilation systems.14 The discussion of the politicisation of the punkah-pulling “system”, which included both the machinery and the operator, also broadens the terms of discussions in Ritam Sengupta’s recent work that focuses “upon the role of regulation and law”, and localised, embodied and embedded practices that became increasingly vital to defining punkah-pulling as a regime of service work in colonial India. For Sengupta, the framing of the relations between punkah-pullers, their employers and the colonial government through the conflicts between control mechanisms of the colonial state, and the caste and social hierarchies within domestic service was crucial in moulding the nature of the initial formalisation and eventual demise of punkah-pulling through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.15 In this article, however, I examine how, through the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the protracted reevaluation and redefinition of punkah-pulling systems evolved into detailed scientific and technological programmes for transforming and deploying both human labour and liberal social agenda. I show that reducing punkah-wallahs as labouring bodies and revealing them only as components in systems of ventilation, the language of promoters’ writings and advertisements contributed significantly to social and technological ideology and debates on interracial violence.

As the first two sections of this article show, discourses on electricity and servants forwarded visions of functional domestic spaces consisting of both servant labour and electrical technologies that required little to almost no intervention from employers and householders. In an immediate sense, promoters’ discourses, though far-reaching, were contradictory. Despite the introduction of electrical technologies in homes and public spaces domestic service was still on the rise. Some forms of domestic service such as child-minding or cooking could obviously not be replaced by electrical technologies. As discussed above, the importance of servants to their employers’ social and cultural identities might also explain the persistence of servants in domestic spaces. However, I offer an alternative explanation based on the actualities of “electrical Calcutta” through the early twentieth century. Electrical technologies could enhance everyday life by bringing with themselves a sense of discipline and morality within domestic spaces. Yet ultimately, the point of using electricity to discipline servants and their labour unsettled the very notion of social and class identities that domestic lives were shaped around. While the use of electrical technologies in the home provided a kind of ordered domestic life, it also implied a failure of the employer to control and discipline servant labour and, therefore, determine their own identities based on differences of class.

In the third section of this article, I shift focus to early electrical consumers who were placed within energy regimes, sources and practices that existed before, alongside and competed for the same spaces and consumers. Of course, there was no single “type of consumer,” and no doubt the ways in which they understood and used electric supply and technologies were highly diverse. But it is possible to identify shared attitudes, practices and ideas that defined the interactions between the electrical enterprise and domestic consumption. One such set of ideas and practices surrounded middle-class domestic ideology based on consumption and thrift in the economic downturn of the early twentieth century; an approach that had a significant impact on the ways middle-class consumers discussed the incorporation of goods, services and electrical technologies into the home. Prospective consumers also had to contend with delayed connections, resulting in existing methods of lighting and ventilation, and servant labour being used often in close proximity to electric lighting and fans.

An important caveat is in order here. The use of predominantly technocratic archives and British and Bengali elite and middle-class writings raises the obvious issue of silencing subaltern voices. The technocratic archive does not speak much about the complex questions of caste and other social divisions prevalent in Indian society.16 Promoters and engineers, as we will see, tried to envisage an “electrical Calcutta” through broad categories of “servants” and “employers”, and interpret and bent the discussions and discourses on employer-servant relationships from wider contemporary literary, public and social circles in Calcutta to capitalist means.

Back to topElectrical Technologies and the Management of Manual Labour and Energy

In one of the first print advertisements of a battery-operated electric bell that appeared in a Bengali periodical in 1890, the new technology is promoted as a means of disciplining servants. The advertisement read:

Electric Bell. No longer will one need to call out to servants and murder them in anger. An approximately 2-feet long cable, a stationery dry battery, and a hook mechanism to attach them will be sent out to your home by paid-for post for a mere 6 rupees. Additional wires, if required, can be acquired at a meagre additional cost. This device, a must for every house, is very useful for people who regularly visit, and are visited by acquaintances, or to send out a message from one’s room in case of need. Whether from the third floor or the underground, this device can be used to call even deaf servants.17 [translation and emphases mine]

In its allusion to servants, the advertisement presents the electric bell’s function and position as an intermediary between the employer and the servant. The electric bell is depicted as a servant to the employer, enabling the employer to carry out his wishes when rung. But, in instructing servants to attend to the employer’s call when they hear the bell, the bell also becomes an extension of the employer’s authority.18 The advertisement also makes us think spatially about employer-servant relations within the household. The fact that servants needed to be called implies either the prevalence of, or the need for physical distance between servants and their employers.19 Efforts by the British and Bengali elite in India to use domestic and public spaces to maintain their prestige and distance from the lower classes were usually undermined by the presence of native servants in the most private spaces of their households. The open plan layout of Anglo-Indian and native domestic spaces in the colonial Indian subcontinent allowed servants to move freely in and occupy the same spaces as their employers.20 According to the advertisement, the electric bell allowed employers to enable and yet manage the physical distance between them and their servants. It suggests that at particular times, employers wished to occupy spaces away from their servants but needed them to be sufficiently close by to be able to answer the bell: “This device, a must for every house, is very useful…to send out a message from one’s room in case of need.” The electric bell, according to contemporary writings, could also save employers the physical exertion of shouting or leaving their homes to call servants who had retreated to their living quarters. In an article on “Electric Bells” in The Times of India of 5 November 1894, the author wrote:

It is to be admitted that our domestic servants in India, despite their manifold virtues, furnish us with a fair share of the sum total of petty troubles in daily life, it is not going far wide of the mark to say that a difficulty in calling them — or rather making them hear — is one of the chief amongst them. The convenience of the bell is enormous, and I am convinced that a large number of headaches and touches of sunstroke would be avoided if people used these bells instead of going outside themselves, in desperation, to call a servant who either does not or will not hear.21

The preoccupation with introducing electric bells to domestic spaces had less to do with replacing servants’ labour than it did with disciplining it. While both the advertisement and the article exemplified the idea of the electric bell as an object with agency and function, especially as a sounding object to call servants, they also suggested its importance as a system for shaping the behaviours of both the employer and the servant. In presenting the electric bell as a device that could be used to call “even deaf servants,” or “a servant who either does not or will not hear,” the writings gesture at the ways in which the bell extended the employer’s authority. While servants could until then choose to ignore their employers’ shouts and calls, the electric bell imposed a certain discipline and ensured that servants acted upon their employers’ commands.22 In solving the simple issue of calling servants, nevertheless, the bell also ensured that employers did not need to expend any energy to either shout at, or even “murder” their servants in desperation or anger.

According to promoters, electrical technologies could help manage both employers’ and servants’ energies by ensuring that employers did not need to expend any mental or physical energy to keep their servants working as they wanted them to while keeping servants active and productive. I return to this theme in the following section when discussing employers’ use of violence on punkah-wallahs who fell asleep during their work shifts.

Indeed, in claiming to enable productivity through disciplining, and sometimes even improving the behaviour of servants, electrical discourses also advanced classist and racial codes. English and Bengali domestic guidebooks warned employers, especially women, to inscribe dishonesty as a natural attribute of servants. These writings not only reflected hierarchical class systems further complicated by race, religion and gender issues as a result of the colonial encounter, but also influenced highly negative attitudes towards servants and the urban poor in general, thereby helping reinforce imperial and class discourses. For instance, Rabindranath Tagore, Swapna M. Banerjee has shown in her study of servants and theft in bhadralok households, regularly wrote about how servants in his household stole expensive yet regularly used items such as ghee (clarified butter) from the kitchen.23 That servants stole at every opportunity was also an often-repeated account in Anglo-Indian literature. In the domestic guidebook, The Englishwoman in India, published in 1864, the unknown author — only mentioned in the book as “A Lady Resident” — suggested that British women should constantly supervise their native servants and expect them to steal food items: “native servants of all classes, good or bad, and indifferent, require the most incessant supervision. […] It is but natural to expect them to pilfer small articles of food: rice, sugar, coffee, and every sort of oil are their specialties in this line.”24 Discussing how the Mussaul, or the “man of lamps,” stole most of the oil and butter he was given to fill the lamps with, Edward Hamilton Aitken, a civil servant and founding member of the Bombay Natural History Society (founded in 1883), wrote in his illustrated journal on life with Indian servants, Behind the Bungalow (1899):

The Mussaul’s name is Mukkun, which means butter, and of this commodity I believe he absorbs a much as he can honestly or dishonestly come by. How else does the surface of him acquire that glossy, oleaginous appearance, as if he would take fire easily and burn well? I wish we could do without him!25

Electrical discourses reinforced these negative attributes by coding electrical appliances as technological solutions to issues of morality and discipline. Echoing prevalent British and bhadralok attitudes towards servants, John Willoughby Meares — then the Electrical Adviser to the Government of India — noted in his book Electrical Engineering in India (1914) that while oil was commonly available and could be easily transported, electricity had “the advantage that even if stolen it cannot usually be sold.”26 To put Meares’s views into perspective, the use of electric lighting in domestic and public spaces was not just for the benefit of electrical suppliers and producers, and the general public; it also served a moral purpose. Electricity took away oil and, according to Montague Massey, a businessman who lived extensively in Calcutta and Bombay from late-nineteenth century onwards, “the great temptation it afforded Gungadeen, the Hindu farash bearer, to annex for his own daily requirements a certain percentage of his master’s [oil] supply.”27

Back to topElectrical and Manual Energies, Violence and Morality

The promotion of electrical technologies were built on several complex layers of nature of work and employer-servant relationships being mapped onto one another, and centred around the operations of existing sources of energy and electrical technologies. Electrical promoters, nevertheless, planted ideas of certain kinds of service, systems and servants as rather problematic. Unlike the images of unruly and thieving servants that could be disciplined by an electric bell or by replacing oil lamps with electric bulbs, the punkah and punkah-wallah embodied all that was wrong with domestic service and ventilation systems in general.

An intrinsically simple cooling and ventilating device, the punkah was a common presence in domestic spaces, writings and images in the Indian subcontinent. While the origins of the punkah are unclear, what we do know is that the punkah appeared and existed in several different forms depending on the spaces and occasions in which they were used. These systems ranged from small hand-held fans — to be used in close proximity — to complex systems of ropes and pulleys that pulled large cloths attached to wooden beams hung from ceilings. The punkah and, most importantly, the punkah-wallah served as mediators between their employers and the natural elements — heat, humidity and mosquitoes. While punkahs and punkah-wallahs were both necessary for cooling and comfort, in late-nineteenth century discussions however, the mechanical systems were considered far more valuable than their human operators. Despite their centrality to the functioning of punkahs, punkah-wallahs were constantly criticised in journalistic writings, memoirs and domestic guidebooks as being inefficient and indolent. A 1901 article on the “question of ventilation” in The Times of India stated that “the chief drawback of the punkah is the punkahwalla. He is dirty, unreliable, especially at night, and his work, counting day and night, costs twenty-four rupees per month for a single punkah.”28 Criticisms of the punkah-wallah were also intrinsically linked to the justification of British imperial rule over India. The punkah-wallah, presented in images and postcards as having a lazy and leisurely approach to his work was, according to colonial narratives, a representative of the “Oriental nature” of Indians who, due to their effeminacy, laziness and dishonesty were incapable of ruling over themselves.29

While employing a punkah-wallah was never expensive, most elite and middle-class households, however, required four to six punkah-wallahs working in four to six-hour shifts in order to keep the punkahs operational throughout the day. This made employing punkah-wallahs an expensive proposition for even the wealthiest households. As Ritam Sengupta has shown in his explorations of punkah-pulling in colonial India, European employers, enabled by direct and indirect mediations of the colonial state, placed greater demands on their native servants’ time and labour.30 The long shifts and demands on their manual energies meant that punkah-wallahs often fell asleep while performing their duties. In his 1896 publication Indian Sketches and Rambles, the anglican clergyman John Bowles Daly wrote about how the punkah-wallah, after a few hours of efficient service, would gradually slow down and finally stop, resulting in complaints from his employer: “For the first hour or two the punkah goes on steadily … Gradually the movement becomes intermittent, and finally ceases, while shouts, and angry complaints arise.”31 An additional cause for criticism was the fact that punkah-wallahs fell asleep during their shifts while their employers had to pay for their services, or lack of it.

The immediate concerns of several writings on the subject of punkahs and punkah-wallahs through the latter half of the nineteenth century were with advancing arguments — some distinctly didactic — that would secure the acceptance of the idea of everyday life without the punkah-wallah. The Times of India of 11 June 1891 carried a column predicting that Calcutta would soon be witness to a new, but experimental installation that “will be for the working of punkah both in large offices and in private houses.” The significance of the new mechanism is clear when we consider the closing sentence of the article: “The abolition of the punkah-wallah in Calcutta would be an important public service.”32 Efforts to “improve” the punkah were prevalent in colonial India well before the introduction of battery-operated or mains powered electric fans in the early twentieth century. This is evident in the persistent proliferation of patents granted by the Government of India to new forms of, or improvements to punkah-pulling systems through the latter half of the nineteenth century. A cursory glance at the list of patents granted between 1856 and 1887 shows that the term “improvement” was most commonly used to define what the list mentions as the “nature of invention”.33 Such “improvements” were majorly directed towards automating punkah-pulling and, therefore, either reducing the number of or completely eliminating the need for punkah-pullers.

Despite the financial savings and convenience that some of these devices claimed to bring to the question of punkah-pulling, the systems were, nevertheless, unable to resolve the problem of the punkah-wallah and issues with ventilation in domestic spaces. Efforts to automate punkah-pulling failed on two levels. Firstly, automation required adding several mechanical elements to the rather simple punkah system, thereby increasing complexity and reducing efficiency. These complex systems could only be efficiently applied to a large number of punkahs, which made them unsuitable for domestic use. Secondly, these mechanical systems, while reducing the number of punkah-wallahs, did not completely eliminate the need for the punkah-wallah.34 The introduction of battery-operated punkah machines was, therefore, seen by many commentators and inventors as the only viable solution to the presence of the punkah-wallah within the domestic sphere. In 1890, in a paper presented to the American Institute of Electrical Engineering, Wilfrid H. Fleming, an American electrical engineer, wrote that manual punkahs were both noisy and caused gas or oil lamps to flicker. Tellingly, Fleming’s only solution to the problems of noise, the flickering of lamps, and the punkah-wallah was to replace both manual punkahs and oil lamps with “noiseless motor fans and steady incandescents [respectively], thus enabling the Anglo-Indian to read and rest in comfort.”35 In early 1890, J. Agabeg, Manager of Messrs. Apcar & Co.’s Collieries at Churrunpore produced a portable electric fan which could be clamped to desks and chairs as per users’ choice. The mechanism “consisting of a motor, two geared wheels, a linked segment lever actuated by a crank and a small pinion, the whole fixed on a carved standard,” could be powered by a refillable copper sulphate battery for up to 14 hours. The fan, Agabeg claimed, could not only replace the punkah-wallah in its operation, but was also much more flexible and cheaper to run than employing a punkah-wallah to pull a punkah fixed permanently to the ceiling.36

While inventors and commentators presented the electrification of punkah-pulling machines as the best means of supplanting manual labour and the punkah-wallah from punkah-pulling systems as well as from domestic spaces, they also deployed the electric punkah and fan to defend the prerogatives of the colonial government in highly politicised issues in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Through the late-nineteenth century, the deaths of punkah-wallahs at the hands of their British and European employers had become tragically commonplace. Newspapers and journals published reports — almost on a fortnightly basis — on the victimisation of punkah-wallahs who unfortunately fell asleep while working, much to the chagrin of those they served. Amrita Bazar Patrika of 6 August 1893 reported: “Hardly a hot season in this country passes, but we read of the death from violence of one or more of that much-abused, but useful, class of menial, the Punkha coolie.”37

Such cases and their regular occurrence became a popular focal point of discussion for vernacular newspapers. What provoked the ire of the vernacular press, however, were not so much the deaths of punkah-wallahs and servants, but the rather lenient sentences handed to European offenders by European judges and juries. While the colonial government in the nineteenth century disavowed interracial white on native violence, the colonial judiciary also worked to reduce inquiries on and penalties for Britons. In colonial India, the declining murder charges against Britons in cases of interracial violence through the latter half of the nineteenth century was never simply a matter of racial inequity, but more a result of the continuing redefinition of factors such as agency and physical contact. Throughout the nineteenth century, British medical observers characterised the Indian body as a source of both legal and medical knowledge, focusing on, as Jordanna Bailkin has noted in her examination of the medico-legal complexities in such cases, “pathologies of the Indian spleen.”38 Reflecting colonial ideas of race, biology and sanitation, medico-legal scholars presented the diseased spleen as a characteristic of Indian bodies owing to malaria and high fevers due to a lack of sanitation. Any Indian person already weakened by an enlarged spleen, these scholars declared, could be killed by any assault that they believed would otherwise be inconsequential. The enlarged spleen that ruptured on account of even the slightest force provided the judicial systems an argument to term such “boot and spleen” cases as accidents instead of murder. Bailkin writes: “The ‘ruptured spleen’ defence — a joint project of colonial law and medicine—provided a compelling judicial framework within which Britons could cause the deaths of Indians without being charged with murder.”39

The colonial government in India, much concerned about the outrage over the “boot and spleen” cases, sought to be “instrumental in relieving the hardships” and reducing the risks to British lives, not the punkah-wallah, by reducing interracial contact. Bailkin explains: “if the impetus to violence was interracial contact, then Curzon saw the reduction of this contact as a humane policy.”40 On 30 March 1904, at the debate on the 1904-1905 budget by the Legislative Council at Government House, Calcutta, Lord Curzon, the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, ordered the removal of punkah-wallahs from all government offices and barracks to be replaced by electric punkahs and fans.41 Electric punkahs and fans were, for the colonial government, a technological solution to a moral and political issue. While punkah-wallahs were victims, losing both lives and employment, it helped, at least for the promoters and inventors of automated punkah machines, to use the politics surrounding the punkah-wallah to their benefit. “Boot and spleen” cases opened up new possibilities for investments in promoting them. On 23 October 1895, Amrita Bazar Patrika published an interview with Babu Bihari Lal Rajak, an employee of the public Works Department in Calcutta who had invented an automatic punkah-pulling machine. Designed to work a clock-work principle using weights, axles and toothed gears, the machine, the inventor claimed, could also be attached to an electric motor to “work a punkah or multiple punkahs from 8 to 9 hours at a time.”42 When asked what motivated his decision to invent the machine, Rajak claimed it stemmed “from the treatment which many poor punkha-coolies received at the hands of their European masters.” Further, “if he could, he thought, invent a practical automatic machine, why, it would not only contribute to the necessary comforts of many people living in the plains of India, but would be the means of saving, in many instances, the lives of poor coolies.”43

Discussions in administrative circles in the early 1890s hinted at the introduction of public electric supply in Calcutta becoming a possibility in the near future. Several inventors saw this as an opportunity to promote their electric punkah machines both as a machine that could save the lives of punkah-wallahs and as a day load for the electric supply scheme. When speaking about his own patented electric punkah machine in 1895, R. J. Browne, an electrician in the British India Steam Navigation Company, saw his machine as a solution to the problems of punkah-pulling and the punkah-wallah “on which so many inventors have worked.”44 Promoting the electric punkah as a replacement for the punkah-wallah, Browne also noted that his machine, once widely accepted by the public, could provide a day load to the upcoming power plant in Calcutta, stating: “On the Calcutta lighting station becoming an established fact this electric punkha-puller would be a boon to the Electric Supply Company as it would enable them to get a day load for their plant which otherwise would be lying idle all day.”45 Brown’s interview also hinted at his belief in his machine as one that could prevent assaults on the punkah-wallah: “this machine should, we think, have a considerable future before it for use in barracks &c., where the punkha coolie is often the cause of much irritation to the men which infrequently leads to ill-treatment of the puller himself.”46

Back to top“Electrical Calcutta” and Consumers’ Realities

While the electric fan was promoted as an effective means of social and financial control over the punkah-wallah, it is a paradox that, despite ordering the installation of electric fans in all government buildings, Lord Curzon himself preferred what he called the “measured sweep” of the manual punkah to what he termed “the hideous anachronism of the revolving blades” of the electric fan.47 While Lord Curzon allowed the installation of electric lifts and lighting in his residence, the Government House in 1900, he employed punkah-wallahs and hand-pulled fans in the Marble Hall and reception rooms in the building.48 While neither contemporary histories of colonial buildings nor Curzon’s biographies elaborate on his decisions, the presence of punkah-wallahs in the public spaces of the building could well be a means of, as discussed in the opening sections of this article, reaffirming and maintaining imperial domesticity and colonial governmentality by presenting punkah-wallahs as surrogates for the colonised.

Advertisements in newspapers and journals can also be an entry point into understanding the changes within the electrical marketplace. Through the first half of the twentieth century, advertisers of electrical goods and services gradually moved away from textual advertisements that conformed to a vocabulary of technical details interspersed with electricity’s value to mundane everyday life. The introduction of public electric supply and the emergence of a domestic consumer market, nevertheless, caused advertisers to use the impersonal voice of middle-class aspirations accompanied by an increasingly sophisticated visual appeal. Through the advertisements, the electrical marketplace now addressed the middle-class, especially men, directly appealing to their sensibilities and definitions of respectability and consumption. An advertisement in The Statesman of May 1915 for the Swan Fan, manufactured by the General Electric Company, shows two seemingly British gentlemen enjoying what the advertisement claims to be the “cool breeze” of the fan in an elite setting. In its iconography, the advertisement depicted not just the kind of consumers who bought and used expensive electric fans — costing “Rs.95 each” — but also portrayed a certain middle-class lifestyle.49

While elites like Curzon could afford to employ both punkah-wallahs and electric fans, for the British and bhadralok middle classes, however, electric supply, lighting and fans were expensive and limited propositions. Even The Electrician, in its December 1903 issue, described the electric light as “not the poor man’s light” in India.50 A battery-operated electric fan cost anywhere between Rs.55 and Rs.110, while a mains-connected overhead electric fan, introduced after 1905, cost between Rs.95 and Rs.125. There were additional costs as well. Electric fans were usually advertised with additional services like oiling, adjusting and repairs, which cost up to an extra Rs.36 per year.51 Electric fans were costly, since British and bhadralok middle-class salaries in the early 1900s averaged between Rs.150 and 200 per month.52 The costs of using electric supply and technologies were also constantly on the rise in the first three decades of the twentieth century, despite assurances by the Calcutta Electric Supply Corporation that growing demands would eventually lower prices. In 1920, in the midst of an economic downturn following the First World War, CESC advertised their inability to accommodate or allow any new installations or extensions by consumers, stating that they were “reluctantly compelled to make this announcement by reasons of the fact that plant on order from England has been held up owing to strikes and other post-War difficulties. If this warning is disregarded it will be impossible for the Corporation to guard against possible breakdowns and interruptions of the supply.”53 In 1922, the Supply Corporation announced an increase in its existing surcharge rates from 15 percent to 30 percent, owing to, as they explained, “the price of coal in Calcutta still remaining very high; and rent, freights, increased taxation in India, and low exchange all reacting unfavourably on the Company’s nett receipts.”54

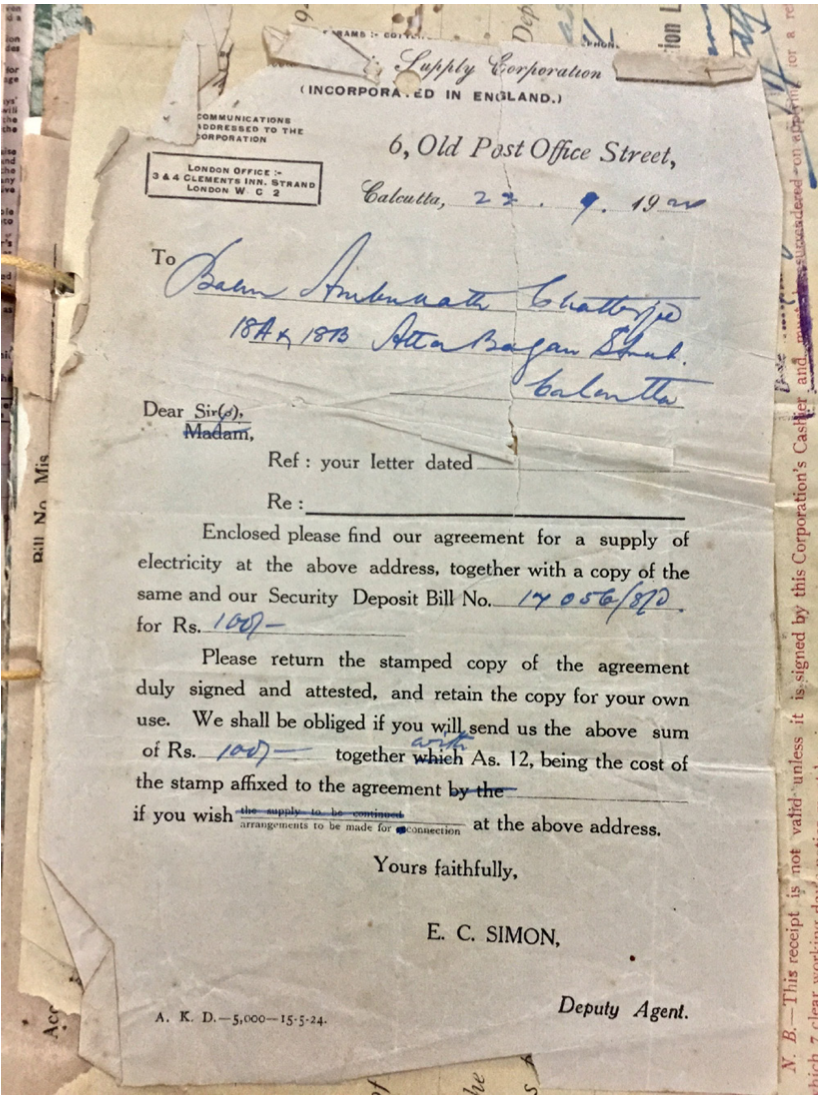

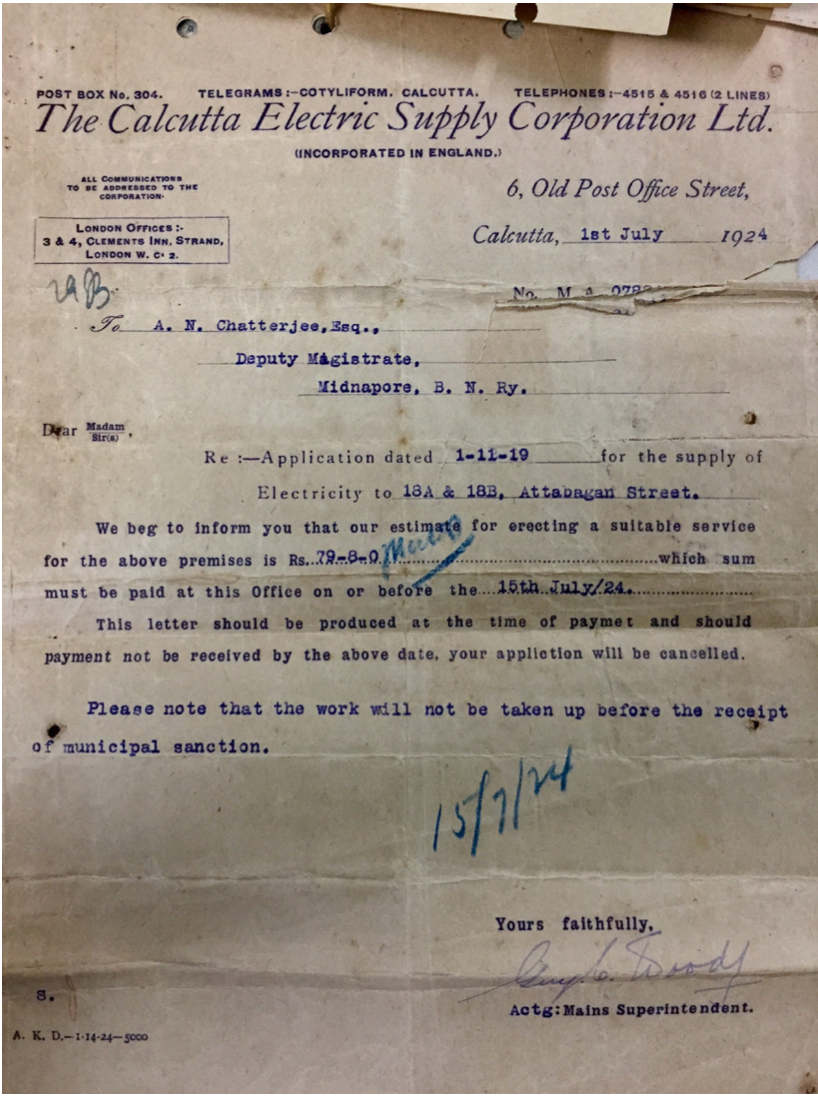

Such bureaucratic and technological factors also affected consumers’ access to electric supply in their homes. What we can infer from some incidental primary sources is how long it actually took for some areas not far outside what historians have termed the “White Town” to gain access to electric supply.55 On 1 November 1919, Ambu Nath Chatterjee, Deputy Magistrate at Midnapore, applied for an electric connection to his residence in Attabagan Street (now Chandibari Street), 3 miles north of the Government House in the colonial centre of Calcutta. After paying an initial deposit of Rs.100 on 22 September 1920 (Figure 1), the application was finally approved by the Electric Supply Corporation after four years when, on 1 July 1924, they demanded a payment of Rs.79 and 8 annas for “erecting suitable service” (Figure 2).

Personal archives such as these, in offering fleeting glimpses of the everyday experiences of electrical consumers and their interactions with suppliers, foreground the ephemeral nature of materials with which we are left to construct stories of electrical consumers and their affective relations with electric supply and technologies.56 They also help us think of the specific sites of production, consumption and practice that create specific affective relationships between materials, bodies, people, spaces and institutions. In electrical advertisements and writings, the success of “electrical Calcutta” was for the most part a matter of disciplining or simply replacing the manual labour of servants with electrical power. Any consequent changes to existing ways of living were, however, dependent on the everyday realities of consumption, class identities, and the inherent limitations of electrical technologies. While the increasing availability of goods and services, including electrical technologies and appliances, to urban dwellers meant that consumption became an essential marker of status in an urban society where caste no longer was an adequate measure of social standing, the uncertain economic and financial situations of early twentieth century resulted in the middle classes rethinking their quotidian spending. This resulted in the development of two “middle-class” viewpoints: firstly, a perception that the urban salaried classes were naturally more extravagant in their quotidian spending and consumption; and secondly, that living beyond one’s means was detrimental and thrift was, therefore, essential.57

Discussions of class, thrift, and rising expenses were, nevertheless, placed squarely within a crowded marketplace where consumers could also choose to use other mechanisms to illuminate and ventilate their homes. Alongside advertisements for, and writings on electric lighting and fans, newspapers also carried advertisements for new and more efficient gas and oil lamps till well into the second half of the twentieth century. Some of these oil lamps, which used ordinary kerosene oil, and claimed to be “punkah and wind proof,” also boasted of safety measures that prevented the theft of oil. These lamps were also much cheaper to install and use than electric lighting. Such advertisements, through their explicit claims and portrayals of oil and gas lamps as being similar to electric bulbs in their design, sought to entice consumers away from electric supply and technologies.58

While many householders considered domestic electric technologies a financial burden, several others based their decisions to continue employing servants on what they considered to be the shortcomings of electrical technologies. At the simplest level, there were questions of spaces in which these technologies were installed. In the early 1900s, expenses entailed by gas supply, plumbing fixtures and electrical wiring were exacerbated by a reduction in domestic square footage while rents increased. The introduction of electric supply came at a time when Calcutta’s population grew exponentially, especially with migrants from villages searching for jobs and opportunities. As Sumit Chakrabarty has shown in The Calcutta Kerani and the London Clerk in the Nineteenth Century, the middle-class which emerged in the nineteenth century, mostly employed in government services and salaried jobs, added to the growing population and even greater demand for already scarce housing.59 As electric supply and technologies in the home continued to be depicted as symbolic of class and social status, by the early 1910s, advertisements for rental properties mentioned electric lighting and fans as staple fixtures, allowing several landlords to ask for higher rents.60 This created economic conditions for the middle classes to continue to rely on non-electrical technologies and the increasing availability of domestic servants and their labour as means of maintaining their ideas of conspicuous consumption and class status. Those that still employed punkah-wallahs also argued that they preferred the non-uniformities of the punkah-wallah’s embodied labour to the mechanical, smooth and uniform motion of electric fans. As The Pioneer noted in an article on “The Punkah-wallah: A Threatened Occupation” published on 3 February 1908, while mechanised and electric fans had seemingly threatened the punkah-wallah’s livelihood over the past few years, the punkah-wallah had managed to, and will continue to survive mainly because all automated systems lacked one significant detail — the necessary “kick” in the punkah’s swing that the punkah-wallah provided with his wrist.61

Back to topConclusion

This article has traced the idea of an “Electrical Calcutta” centred on shifting discussions from the labour of human bodies to electrical technologies. This transition and its promotion was, however, a cultural process as much as a technical one. Discussions and visions of an “Electrical Calcutta” depended materially and discursively on the complexities and interconnectedness of employer-servant relationships, class and social identities, human bodies and labour, and sources of fuel and energy. By seeking out some of the concerns about the presence of servants within British and bhadralok lives and spaces that were articulated within and through writings and advertisements promoting electrical appliances, we find that such promotions did not simply depend on the efficiencies and comforts of said technologies as compared to existing servant labour and means of lighting and ventilation. Instead, promoters and commentators relied on presenting electric power as rhetorical and technological solutions to social and moral issues of disciplining and shaping servant labour and energy, managing and reducing employers’ efforts, and preventing interracial violence. Thus, notions of efficiency, morality, behaviour, hierarchy became central to promoters’ visions of an electrical future.

While teleological and progressive historical accounts of “electrification” have presented transitions to electrical power and appliances as moments of straightforward acceptance and dramatic move towards modernity, this article has instead also highlighted the continuities in the history of electricity and energy.62 Looking closely at periods and visions of transition gives us a much better perspective of how actors, societies, industries and institutions responded to shifts in energy regimes and practices. And so the path to “Electrical Calcutta”, especially as promoters had envisioned, was fairly complex and seldom straightforward.

- 1. R. W. Ashcroft, “Electrical Calcutta”, The Electrical World and Engineer, 7 July 1900, 14.

- 2. Id.

- 3. Id.

- 4. Id.

- 5. Douglas E. Haynes, “Creating the consumer? Advertising, Capitalism, and the Middle Class in Urban Western India”, in Douglas E. Haynes, Abigail McGowan, Tirthankar Roy and Haruka Yanagisawa (eds.), Towards a History of Consumption in South Asia (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2010), 185-223. David Arnold, Everyday Technology: Machines and the Making of India’s Modernity (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2013), 122-126, 146. In Everyday Technology, David Arnold has shown that mass advertising campaigns and their portrayal of technologies such as sewing machines, bicycles and typewriters as means to a healthy and rewarding life were crucial to their acceptance by the Indian public.

- 6. Graeme Gooday, Domesticating Electricity: Technology, Uncertainty and Gender, 1880-1914 (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2008), 33-35.

- 7. Diana J. Montaño, Electrifying Mexico: Technology and the Transformation of a Modern City (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2021), 194-195, 215-232.

- 8. For a detailed review of other discussions on domestic service in energy histories, see Ruth W. Sandwell, “Changing the Plot: Including Women in Energy History (and Explaining Why They Were Missing)”, in Abigail Harrison Moore and Ruth W. Sandwell (eds.), In a New Light: Histories of Women and Energy (London: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2021), 16-45.

- 9. Satyasikha Chakraborty, “Technologies of domestic labour” https://servantspasts.wordpress.com/2017/10/16/domestic-gadgets-and-dom…. Accessed 17 February 2021. Also see: Nitin Sinha and Nitin Varma (eds.), Servants’ Pasts: Late-Eighteenth to Twentieth-Century South Asia, Vol.II (New Delhi: Orient Blackswan, 2019)

- 10. Fae Dussart, “The Servant/Employee Relationship in Nineteenth Century England and India” (Ph.D diss., University of London, 2005), 87. Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database, UMI NO. U591979. Also see: Dussart, “That unit of civilisation and the talent peculiar to women: British employers and their servants in the nineteenth-century Indian empire”, Identities, vol. 22/6, 2015, 706-721. Robin D. Jones, Interiors of Empire: Objects, Space and Identity Within the Indian Subcontinent, c. 1800-1947 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007), 2.

- 11. Flora Annie Steel and Grace Gardiner, The Complete Indian Housekeeper and Cook, 5th edition (London: Heinemann, 1907, first published in 1877), 7-9. Nupur Chaudhuri, “Memsahibs and Motherhood in Nineteenth-Century Colonial India”, Victorian Studies, vol. 31/4, 1988, 517-535.

- 12. Partha Chatterjee, “The Nationalist Resolution of the Women Question”, in Kumkum Sangari and Sudesh Vaid (eds.), Recasting Women: Essays in Colonial History (Delhi: Kali for Women, 1989), 233-253. For a critical view on Chatterjee’s formulation of the place of women in bhadralok discourses on “home” and the “outside”, see: Tanika Sarkar, “The Hindu Wife and the Hindu Nation: Domesticity and Nationalism in Nineteenth Century Bengali”, Studies in History, vol. 8/2, 1992, 213-235.

- 13. Swapna M. Banerjee, “Debates on Domesticity and the Position of Women in Late Colonial India”, History Compass, vol. 8/6, 2010, 455-473. “Subverting the Moral Universe: ‘Narratives of Transgression’ in the Construction of Middle-class Identity in Colonial Bengal”, in Crispin Bates (ed.), Beyond Representation: Colonial and Postcolonial Construction of Indian Identity (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2006), 77-99. Men, Women, and Domestics: Articulating Middle-Class Identity in Colonial Bengal (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004). Also see: Swati Chattopadhyay, “Blurring Boundaries: The Limits of ‘White Town’ in Colonial Calcutta”, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, vol. 59/2, June 2000, 154-179.

- 14. Jordanna Bailkin, “The Boot and the Spleen: When Was Murder Possible in British India?”, Society for Comparative Study of Society and History, vol. 48/2, 2006, 462-493.

- 15. Ritam Sengupta, “Keeping the master cool, every day, all day: Punkah-pulling in colonial India”, The Indian Economic and Social History Review, 2021, 1–37, quote from 4.

- 16. See: Tanika Sarkar, “Caste-ing Servants in Colonial Calcutta”, in Nitin Sinha and Nitin Varma (eds.), Servants’ Pasts: Late Eighteenth to Twentieth-Century South Asia, Vol.2 (New Delhi: Orient Blackswan, 2019). Also: Sengupta, “Keeping the master cool”, 1–37.

- 17. Citradarsana, Vol. 1, 1890, 36. Online version of the journal hosted by CrossAsia-Repository and Heidelberg University Library, while microfilm and paper copies of the journal are held by the archives of the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Kolkata, and the Bangiya Sahitya Parishat in Kolkata, respectively.

- 18. For an analysis of the complex dynamics of material culture, the sensory dimensions of objects, and human relationships within the household, see Flora Dennis, “Material Culture and Sound: A Sixteenth Century Bell”, in Anne Gerritsen and Giorgio Riello (eds.), Writing Material Culture History (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), 151-156.

- 19. In the homes of Bengali and Anglo-Indian elites, the living spaces of employers and servants were usually separate and distant from each other. Servants in elite households in colonial India usually lived with their families in huts within the compounds of their employers’ bungalows. See: Fae Dussart, “The Servant/Employee Relationship in Nineteenth Century England and India” (Ph.D diss., University of London, 2005), 87. Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database, UMI No.: U591979. Also see: Dussart, “That unit of civilisation and the talent peculiar to women : British employers and their servants in the nineteenth-century Indian empire”, Identities, vol. 22/6, 2015, 706-721. William J. Glover, “A Feeling of Absence from Old England: The Colonial Bungalow”, Home Cultures, vol. 1/1, 2004, 61-82.

- 20. Jones, The Interiors of Empire, 81.

- 21. “Electric Bells”, The Times of India, 5 November 1894, 4.

- 22. Unfortunately, there are no studies on sounds and hearing as central to social, domestic and ritual life in colonial India. However, in their study of hearing loss in Britain c.1830-1930, Graeme Gooday and Karen Sayer have shown the ways in which the term “deaf” was an “unsympathetic representation of the hard of hearing” as those who “could in fact hear more effectively than they claimed, but simply ‘chose’ stubbornly not to hear.” Graeme Gooday and Karen Sayer, Managing the Experience of Hearing Loss in Britain, 1830-1930 (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 19.

- 23. Banerjee, Men, Women, and Domestics, 166-175. Also see: Rabindranath Tagore, Jiwansmriti (Calcutta: Vishwa-Bharti Granthabibhag, 1912), 24.

- 24. Anon. (A Lady Resident), The Englishwoman in India (London: Smith, Elder and Co., 1864), 58.

- 25. Edward Hamilton Aitken, Behind the Bungalow (Calcutta: Thacker, Spink and Co., 1889), 52.

- 26. J.W. Meares, Electrical Engineering in India - A Practical Treatise for Civil, Mechanical and Electrical Engineers (Calcutta: Thacker, Spink and Co., 1914), 102 (hereafter Electrical Engineering in India). Archived in IOR: Asia, Pacific and Africa/T 3659.

- 27. Montague Massey, Recollections of Calcutta For Over Half a Century (Calcutta: Thacker, Spink and Co., 1918), 64. Farash: “A menial servant whose proper business is to spread carpets, pitch tents, &c., and, in fact, in a house, to do housemaid's work”; definition from Henry Yule and A.C. Burnell, Hobson-Jobson: The Anglo-Indian Dictionary (Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Reference, 1996, originally published in 1886), 350.

- 28. “Buildings in Bombay: The Question of Ventilation in the New Houses, An Excellent Suggestion”, The Times of India, 2 November 1901, 7.

- 29. Steven Patterson, “Postcards from the Raj”, Patterns of Prejudice, vol. 40/2, 2006, 152-153.

- 30. Sengupta, “Keeping the master cool”, 2 and 24.

- 31. John Bowles Daly, Indian Sketches and Rambles (Calcutta: Patrick Press, 1896), 64.

- 32. The Times of India, 11 June 1891, 5.

- 33. List of Patents Granted / India (Calcutta: Government Press, 1856-1887). Archived at the British Library: Asia Pacific & Africa IOR/V/25/600, Holdings: 1856-1887.

- 34. The Bombay Gazette, 29 January 1862, 100. The Pioneer, 18 September 1875, 2.

- 35. Wilfrid H. Fleming, “Electric Lighting in the Tropics”, Transactions of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, vol. 7/1, November 1890, 168.

- 36. “Automatic Portable Electric Fan”, Amrita Bazar Patrika, July 3, 1890, 8.

- 37. Amrita Bazar Patrika, 6 August 1893, 6.

- 38. Bailkin, “The Boot and the Spleen”, 477-478 and 483.

- 39. Ibid., 481.

- 40. Ibid., 486.

- 41. George Nathaniel Curzon and T. Raleigh (eds.), Lord Curzon in India; Being a Selection from His Speeches as Viceroy and Governor-General of India, 1898-1905 (London: Macmillan, 1906), 406.

- 42. Amrita Bazar Patrika, 23 October 1895, 5.

- 43. Id.

- 44. “An Electric Punkha Machine”, The Pioneer, 5 September 1895, 4.

- 45. Id.

- 46. Id.

- 47. N. V. H. Symons, The Story of Government House (Alipore: Bengal Government Press, 1935), 35-36.

- 48. Id.

- 49. “Advertisement for Swan Fan”, The Statesman, May 1915.

- 50. The Electrician, No. 1333, vol. 7/52, 4 December 1903, 245-247.

- 51. Advertisement for a battery-operated electric fan in The Statesman, November 1901 and Advertisement for electric punkah in The Statesman, February 1900.

- 52. Massey, Recollections of Calcutta, 47-48.

- 53. Amrita Bazar Patrika, April 1920, 2.

- 54. Amrita Bazar Patrika, 29 July 1922, 2.

- 55. I borrow my definition of the colonial centre and “White Town” from Partho Datta, Planning the City: Urbanisation and Reform in Calcutta, c.1800 - c.1940 (New Delhi: Tulika Books, 2012), 13.

- 56. For a discussion on the transactional value of personal archives, see Catherine Hobbs, “The character of personal archives: Reflections on the value of records of individuals”, Archivaria, 2001, 126-135. For a discussion on bureaucratic record-keeping and the dominance of paper records in interactions with organisations, businesses or governments in colonial and postcolonial South Asia, see Bhavani Raman, Document Raj: Writing and Scribes in Early Colonial South India (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2012) and Matthew S. Hull, Government of Paper: The Materiality of Bureaucracy in Urban Pakistan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012).

- 57. Prashant Kidambi, “Consumption, Domesticity and the Idea of the ‘Middle Class’ in Late Colonial Bombay”, in Sanjay Joshi (ed.), The Middle Class in Colonial India (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2011), 132-155. Douglas Haynes, Abigail McGowan, Tirthankar Roy and Haruka Yanagisawa (eds.), Towards a History of Consumption in South Asia (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2010). Abigail McGowan, “Consuming Families: Negotiating women’s shopping in early twentieth century Western India”, in Haynes, McGowan et.al. (eds.), Towards a History of Consumption, 161.

- 58. Advertisements for “Punkah and Wind Proof Lamp” in The Statesman, August 1878 and December 1925.

- 59. Sumit Chakrabarty, The Calcutta Kerani and the London Clerk in the Nineteenth Century (New York: Routledge, 2021), 1-62.

- 60. “To-Let Listings” from The Statesman, October 1903 and June 1915, collected in Ranabir Ray Choudhury, Early Calcutta Advertisements, 1875-1925: A Selection from The Statesman (Calcutta: The Statesman Commercial Press, 1992), 298 and 308.

- 61. “The Punkah-wallah: A Threatened Occupation”, The Pioneer, 3 February 1908, 6.

- 62. This article is built on other examinations of “continuities” in electrical and energy histories, please see: Karen Sayer, “Atkinson Grimshaw, Reflections on the Thames (1880): Explorations in the Cultural History of Light and Illumination”, Annali di Ca’ Foscari Serie occidentale, vol. 51, 2017, 131. Ute Hasenöhrl, “Rural Electrification in the British Empire”, History of Retailing and Consumption, vol. 4/1, 2018, 14-15 and “Contested nightscapes: Illuminating colonial Bombay”, Journal of Energy History / Revue d’Histoire de l’Energie, vol. 2, June 2019. Animesh Chatterjee, ‘“New wine in new bottle’: class politics and the ‘uneven electrification’ of colonial India”, History of Retailing and Consumption, vol. 4/1, 2018, 94-108. Ronald R. Kline, “Resisting Consumer Technology in Rural America: The Telephone and Electrification”, in Nelly Oudshoorn and Trevor Pinch (eds.), How users matter: The co-construction of users and technologies (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003), 51-66.

Primary Sources

Aitken, Edward Hamilton, Behind the Bungalow (Calcutta: Thacker, Spink and Co., 1889).

Anon. (A Lady Resident), The Englishwoman in India (London: Smith, Elder and Co., 1864).

Ashcroft, R. W., “Electrical Calcutta”, The Electrical World and Engineer, vol. 36/ 1, 7 July 1900, 14.

Buckland, C. T., “Men-Servants In India”, The National Review (London), vol. 18/107, January 1892, 663-674.

Curzon, George Nathaniel, British Government in India 2 vols. (London: Cassell, 1925).

Curzon, George Nathaniel and Raleigh, T. (eds.), Lord Curzon in India; Being a Selection from His Speeches as Viceroy and Governor-General of India, 1898-1905 (London: Macmillan, 1906).

Daly, John Bowles, Indian Sketches and Rambles (Calcutta: Patrick Press, 1896).

Duncan, Sara Jeannette, On the Other Side of the Latch (London, 1901).

Fleming, Wilfrid H., “Electric Lighting in the Tropics,” Transactions of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, vol. 7/1, November 1890, 168-174a.

Massey, Montague, Recollections of Calcutta For Over Half a Century (Calcutta: Thacker, Spink and Co., 1918).

Meares, J. W., Electrical Engineering with particular references to Conditions in Bengal (Six Lectures delivered in March 1900 at the Civil Engineering College, Sibpur) (Calcutta: Bengal Secretariat Press, 1900). British Library India Office Records IOR: Asia, Pacific & Africa/V9417.

Meares, J. W., Electrical Engineering in India - A Practical Treatise for Civil, Mechanical and Electrical Engineers (Calcutta: Thacker, Spink and Co., 1914). IOR: Asia, Pacific and Africa/T 3659.

Meares, J. W., Electrical Engineering Practice: A Practical Treatise for Civil, Mechanical and Electrical Engineers (London: E. & F. N. Soon Ltd., 1917). IOR: General Reference Collection 08755.C.I.

Meares, J. W., List of Patents Granted / India (Calcutta : Government Press, 1856-1887). Archived at the British Library: Asia Pacific & Africa IOR/V/25/600, Holdings: 1856-1887.

Steel, Flora Annie and Gardiner, Grace, The Complete Indian Housekeeper and Cook, 5th edition (London: Heinemann, 1907).

Symons, N. V. H., The Story of Government House (Alipore: Bengal Government Press, 1935).

Yule, Henry and Burnell, A. C., Hobson-Jobson: The Anglo-Indian Dictionary (Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Reference, 1996, originally published in 1886).

Bengali Periodicals / Journals

Online versions of the following periodicals/journals are hosted by CrossAsia-Repository and Heidelberg University Library.

Amrita Bazar Patrika (Calcutta, Patrika Press, c. 1868-1905). Also published in English.

Bamabodhini Patrika (Calcutta: Bamabodhini Sabha, c. 1863-1922).

Basntak (Calcutta: Board of Principals, Chorbagan Balika Bidyalaya, c. 1874-1875).

Chitradarsana (Calcutta: Artist Press, c. 1890-1891).

English Periodicals / Journals

The Bombay Gazette (Bombay).

The Calcutta Gazette (Calcutta).

The Calcutta Review (Calcutta: Thacker, Spink & Co.).

The Electrician (London).

The Electrical Review (London).

The Hindoo Patriot (Calcutta).

Journal of Electricity, Power and Gas (San Francisco).

The Journal of Gas Lighting, Water Supply & Sanitary Improvement (London).

Popular Electricity (Chicago).

The Pioneer (Allahabad).

The Statesman (Calcutta).

The Times of India (Bombay).

Secondary Sources

Arnold, David, Everyday Technology: Machines and the Making of India’s Modernity (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2013).

Bailkin, Jordanna, “The Boot and the Spleen: When Was Murder Possible in British India?”, Society for Comparative Study of Society and History, vol. 48/2, 2006, 462-493.

Banerjee, Swapna M., “Debates on Domesticity and the Position of Women in Late Colonial India”, History Compass, vol. 8/6, 2010, 455-473.

Banerjee, Swapna M., “Subverting the Moral Universe: ‘Narratives of Transgression’ in the Construction of Middle-class Identity in Colonial Bengal”, in Crispin Bates, ed., Beyond Representation: Colonial and Postcolonial Construction of Indian Identity (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2006), 77-99.

Banerjee, Swapna M., Men, Women, and Domestics: Articulating Middle-Class Identity in Colonial Bengal (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004).

Banerjee, Swapna M., “DownMemory Lane: Representation of Domestic Workers in Middle-Class Personal Narratives of Colonial Bengal”, The Journal of Social History, vol. 37/3, Spring 2004, 681-708.

Basu, Sudipto, “Spatial Imagination and Development in Colonial Calcutta, c 1850-1900”, History and Sociology of South Asia, vol. 10:1, 2016, 35-52.

Chakraborty, Bidisha and De, Sarmistha, Calcutta in the Nineteenth Century: An Archival Exploration (New Delhi: Niyogi Books, 2013).

Chatterjee, Animesh, “‘New wine in new bottles’: class politics and the ‘uneven electrification’ of colonial India”, History of Retailing and Consumption, vol. 4/1, 2018, 94-108.

Chatterjee, Partha, “The Nationalist Resolution of the Women Question”, in Kumkum Sangari and Sudesh Vaid (eds.), Recasting Women: Essays in Colonial History (Delhi: Kali for Women, 1989), 233-253.

Chattopadhyay, Swati, Representing Calcutta: Modernity, Nationalism, and the Colonial Uncanny (London and New York: Routledge, 2005).

Chattopadhyay, Swati, “Blurring Boundaries: The Limits of ‘White Town’ in Colonial Calcutta”, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, vol. 59/2, June 2000, 154-179.

Chaudhuri, Nupur, “Memsahibs and Motherhood in Nineteenth-Century Colonial India”, Victorian Studies, vol. 31/4, 1988, 517-535.

Chaudhuri, Sukanta (ed.), Calcutta: The Living City, Vols.I and II (Calcutta: Oxford University Press, 1990).

Coleman, Leo, A Moral Technology: Electrification as Political Ritual in New Delhi (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2017).

D’Souza, Rohan, Drowned and Dammed: Colonial capitalism and flood control in Eastern India (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2006).

Datta, Partho, “How Modern Planning Came to Calcutta”, Planning Perspectives, vol. 28/1, 2013, 139-147.

Datta, Partho, Planning the City: Urbanisation and Reform in Calcutta, c.1800 — c.1940 (New Delhi: Tulika Books, 2012).

Dennis, Flora, “Material Culture and Sound: A Sixteenth Century Bell”, in Anne Gerritsen and Giorgio Riello (eds.), Writing Material Culture History (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), 151-156.

Dussart, Fae, “The Servant/Employee Relationship in Nineteenth Century England and India” (Ph.D diss., University of London, 2005). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database, UMI No.: U591979.

Dussart, Fae, “That unit of civilisation and the talent peculiar to women : British employers and their servants in the nineteenth-century Indian empire”, Identities, vol. 22/6, 2015, 706-721.

Fernandes, Leela, “The Politics of Forgetting: Class Politics, State Power and the Restructuring of Urban Space in India”, Urban Studies, vol. 41/12, November 2004, 2415-2430.

Glover, William J., “A Feeling of Absence from Old England: The Colonial Bungalow”, Home Cultures, vol. 1/1, 2004, 61-82.

Gooday, Graeme, Domesticating Electricity: Technology, Uncertainty and Gender, 1880-1914 (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2008).

Gooday, Graeme and Sayer, Karen, Managing the Experience of Hearing Loss in Britain, 1830-1930 (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017).

Hasenöhrl, Ute, “Rural Electrification in the British Empire”, History of Retailing and Consumption, vol. 4/1, 2018, 10-27.

Hasenöhrl, Ute, “Contested nightscapes: Illuminating colonial Bombay”, Journal of Energy History / Revue d’Histoire de l’Energie, vol. 2, June 2019.

Haynes, Douglas E., “Advertising and the History of South Asia 1880-195”, History Compass, vol. 13/8, 2015, 361-374.

Haynes, Douglas E., “Creating the consumer? Advertising, Capitalism, and the Middle Class in Urban Western India”, in Douglas E. Haynes, Abigail McGowan, Tirthankar Roy and Haruka Yanagisawa (eds.), Towards a History of Consumption in South Asia (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2010), 185-223.

Haynes, Douglas E., McGowan, Abigail, Roy, Tirthankar and Yanagisawa, Haruka (eds.), Towards a History of Consumption in South Asia (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2010).

Hobbs, Catherine, “The character of personal archives: Reflections on the value of records of individuals”, Archivaria, 2001, 126-135.

Hull, Matthew S., Government of Paper: The Materiality of Bureaucracy in Urban Pakistan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012).

Jain, Sarandha, “Building ‘oil’ in British India: a category, an infrastructure”, Journal of Energy History [online], vol. 3, April 2020, url: energyhistory.eu/en/node/185.

Jones, Robin D., Interiors of Empire: Objects, Space and identity within the Indian Subcontinent, c.1800–1947 (Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 2007).

Joshi, Sanjay (ed.), The Middle Class in Colonial India (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2011).

Joshi, Sanjay (ed.), Fractured Modernity: Making of a Middle Class in Colonial North India (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2001).

Joyce, Patrick (ed.), The Middle Class in Colonial India (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2010).

Kale, Sunila S., Electrifying India: Regional Political Economies of Development (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2014).

Kale, Sunila S., “Structures of Power: Electrification in Colonial India,” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, vol. 34/3, 2014, 454-475.

Kidambi, Prashant, “Consumption, Domesticity and the Idea of the ‘Middle Class’ in Late Colonial Bombay”, in Sanjay Joshi (ed.), The Middle Class in Colonial India (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2011), 132-155.

Kline, Ronald R., Consumers in the Country: Technology and Social Change in Rural America (London: The Johns Hopkins Press, 2000).

Kline, Ronald R., “Resisting Consumer Technology in Rural America: The Telephone and Electrification”, in Nelly Oudshoorn and Trevor Pinch (eds.), How users matter: The co-construction of users and technologies (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003), 51-66.

McGowan, Abigail, “Consuming Families: Negotiating women’s shopping in early twentieth century Western India”, in Haynes, McGowan et.al. (eds.), Towards a History of Consumption, 155-184.

Montaño, Diana J., Electrifying Mexico: Technology and the Transformation of a Modern City (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2021).

Moore, Abigail Harrison and Sandwell, Ruth W. (eds.), In a New Light: Histories of Women and Energy (London: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2021).

New Daggett, Cara, The Birth of Energy: Fossil Fuels, Thermodynamics and the Politics of Work (London: Duke University Press, 2019).

Nye, David E., American Illuminations: Urban Lighting, 1800-1920 (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2018).

Nye, David E., Electrifying America: Social Meanings of a New Technology, 1880-1940 (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1990).

Osterhammel, Jürgen, The Transformation of the World: A Global History of the Nineteenth Century, translated by Patrick Camiller (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014).

Oudshoorn, Nelly and Pinch, Trevor (eds.), How users matter: The co-construction of users and technologies (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003).

Patterson, Steven, “Postcards from the Raj”, Patterns of Prejudice, vol. 40/2, 2006, 142-158.

Raman, Bhavani, Document Raj: Writing and Scribes in Early Colonial South India (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2012).

Srinivasa, Rao Yenda, “Electricity, Politics and Regional Economic Imbalance in Madras Presidency, 1900-1947”, Economic & Political Weekly, vol. 14/23, 5 June 2010, 59-66.

Srinivasa, Rao Yenda and Lourdusamy, John, “Colonialism and the Development of Electricity: The Case of Madras Presidency, 1900-47,” Science, Technology and Society, vol. 15/27, 2010, 27-54.

Ray, Choudhury Ranabir, Early Calcutta Advertisements 1875-1925: A Selection from The Statesman (Calcutta: The Statesman Commercial Press, 1992).

Ray, Choudhury Ranabir, Calcutta: A Hundred Years Ago (Calcutta: The Statesman Commercial Press, 1987).

Sandwell, Ruth W., “Changing the Plot: Including Women in Energy History (and Explaining Why They Were Missing)”, in Abigail Harrison Moore and Ruth W. Sandwell (eds.), In a New Light: Histories of Women and Energy (London: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2021), 16-45.

Sarkar, Suvobrata, “Electrification of Colonial Calcutta: A Social Perspective”, Indian Journal of History of Science, vol. 53/4, 2018, 211-216.

Sarkar, Suvobrata, “The Electrification of Colonial Calcutta: Role of the Innovators, Bureaucrats and Foreign Business Organization, 1880–1940”, Studies in History, vol. 34/1, 2018, 48–76.

Sarkar, Suvobrata, “Domesticating electric power: Growth of industry, utilities and research in colonial Calcutta”, The Indian Economic and Social History Review, vol. 52/3, 2015, 357-389.

Sarkar, Tanika, “The Hindu Wife and the Hindu Nation: Domesticity and Nationalism in Nineteenth Century Bengal”, Studies in History, vol. 8, 1992, 213–235.

Sengupta, Ritam, “Keeping the master cool, every day, all day: Punkah-pulling in colonial India”, The Indian Economic and Social History Review, 2021, 1–37.

Sharma, Madhuri, “Creating a Consumer: Exploring Medical Advertisements in Colonial India,” in Biswamoy Pati and Mark Harrison (eds.), The Social History of Health and Medicine in Colonial India (Oxon: Routledge, 2009).

Shutzer, Matthew, “Energy in South Asian history”, History Compass, vol. 18/e12635, 2020. url: https://doi.org/10.1111/hic3.12635.

Sinha, Nitin, “Who Is (Not) a Servant, Anyway? Domestic servants and service in early colonial India”, Modern Asian Studies, 2020, 1-55.

Sinha, Nitin and Verma, Nitin (eds.), Servants’ Pasts: Late-Eighteenth to Twentieth-Century South Asia, Vol. 2 (New Delhi: Orient Blackswan, 2019).

Walsh, Judith E., Domesticity in Colonial India: What Women Learned when Men Gave Them Advice (Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004).