Relieving the housewife: Gender and the promise of geothermal district heating in Reykjavík, 1930s–1970s

Maastricht University

o.melsted[at]maastrichtuniversity.nl

twitter : @odinnmelsted

This article builds on research funded by a DOC-fellowship of the Austrian Academy of the Sciences at the Institute of History and European Ethnology of the University of Innsbruck during 2017–2020, and a scholarship of the Landsvirkjun Energy Research Fund (Orkurannsóknasjóður) in 2017.

Between 1939 and 1944, the City of Reykjavík in Iceland built a geothermal district heating utility that enabled the inhabitants to transition from coal to geothermal heating. One of the promises that geothermal proponents made to the inhabitants was that the utility would relieve the housewives of their coal stoking duties. In this article, I examine the gender and energy justice implications of the changes in residential energy use in Reykjavík between the 1930s and 1970s. In particular, the role of women in the use of local biofuels and imported coal for household energy needs, the use of hot springs for laundry, and how the introduction of geothermal heating changed the lives of the inhabitants. Housewives mattered for the geothermal transition, which improved their work and lives. Yet the geothermal transition also created new challenges, new injustices among connected and unconnected households, and did not necessarily reduce the workload for women or revolutionize their societal roles.

Introduction

In 1943–1944, the City of Reykjavík completed one of the largest infrastructure project in its history: the construction of a city-wide geothermal district heating utility. District heating infrastructures to transmit hot water or steam via a grid were built in many cities in the late 19th and early 20th C., for instance New York or Copenhagen, and later spread even to the smallest villages.1 Today, millions of people rely on district heating, especially in Eastern Europe, the Baltics and Scandinavia, where more than half of the population is connected to district heating, topped by Iceland, with about 90 percent of the population.2 Those district heating utilities were generally built and operated by communal governments or publicly owned utility companies, and intended to replace individual heating with coal ovens, which were labour-intensive in handling and caused alarming smoke pollution in residential areas. District heating served to increase energy efficiency in urban heating, and to provide equal access to reliable and affordable heating. Most district heating utilities burn fuel (and waste) to heat up water, whereas Icelandic systems are unique because they are generally supplied with hot water from geothermal wells.3 During the 1930s, the proponents of district heating in Reykjavík also made a special promise to the housewives: that it would relieve them of their coal stoking duties. Those tasks were indeed disliked among women and made the geothermal project highly popular with them. Its proponents even framed the geothermal project as a “housewives’ cause” – or rather a “housemothers’ cause” (málefni húsmæðranna), as Icelanders called it at the time.4

Iceland is often considered a model country in renewable (or low-carbon) energy use. Today, 9 out of 10 houses – particularly in Reykjavík and the surrounding Capital Area – are supplied by geothermal district heating utilities, and the remainder is heated with electricity. In addition, nearly all of the island’s electricity is supplied by hydroelectric and geothermal power plants.5 Most Icelandic households therefore benefit from relatively cheap communal energy services, as geothermal energy has generally become much cheaper than fuel-based heating. The annual cost of heating in Reykjavík, for example, is much lower than in other Nordic Capitals, only one third of that in Oslo, Stockholm or Copenhagen, and one fifth of that in Helsinki.6 The historical shift to geothermal heating is generally thought of as having been beneficial for Icelanders, as has been argued with calculations of the accumulated savings of fuel imports and CO2 emissions avoided in the space heating sector.7 Iceland is also often considered a model country in terms of gender equality. Iceland was fairly early to introduce female voting rights in parliamentary elections in 1915 and elected Vigdís Finnbogadóttir as president in 1980, who was the world’s first female and democratically elected head of state at the time.8 Nowadays, Iceland often ranks first regarding equal pay, women’s rights and participation of women in the workforce.9 What exactly was it that the city’s engineers and politicians – all male, of course – were promising to the female population of Reykjavík in the 1930s? Did geothermal district heating serve the goal of emancipating women in society? What was the role of women in the introduction of geothermal heating?

In dealing with those questions, I draw from two strands of scholarly inquiry: the historiography of residential energy use and the social scientific study of energy justice. The international historiography of energy has long tended to represent production and distribution of energy more than consumption perspectives, as most research has been done on energy companies and supply policies, but less about the consumers of energy. The relatively little work that has been done on district heating is a case in point. Most works on the history of (geothermal) district heating in Iceland, for instance, are typical utility histories, commissioned to document the history of a particular utility company.10 In doing so, they deal with mayors, engineers and infrastructure projects, but devote less attention to consumers of geothermal heating and even less to women as energy consumers.11 Internationally, there has been considerable research on consumers of energy, and with it the role of women in different forms of residential energy use and their role in transitions. Gender aspects of energy history have thereby been explored for various forms of residential energy use with electric appliances as well as space heating practices.12 As that work has shown, the agency of women – like that of consumers in general – might not be obvious, and harder to trace in the historical evidence, but should nevertheless be included in historical analysis. The most essential sources for this case study are contemporary newspapers and magazines, and the Icelandic National Museum’s questionnaires preserving memories of everyday life (mainly compiled in the 2010s). Those sources confirm that it is not only interesting but also necessary to examine the role of women in the history of geothermal heating. The introduction of geothermal heating changed the lives and work of housewives and the promise to relieve them of their unpopular coal stoking duties was an integral part of the campaign for the geothermal project.

The second strand I draw from is the literature on energy justice. This social scientific research field has highlighted the disparities in energy use, particularly distributive (in)justice, as not all members of society have equal access to the same energies.13 Gender injustices have been identified as an important issue next to class or ethnicity, but scholarship has mainly focused on the under-representation of women in energy companies and energy-related policy and decision-making, rather than energy use itself.14 Similar to the historiography of energy, the historical evolution of district heating has been little represented in the energy justice literature, and with it questions of gender roles and inequalities regarding heating utilities.15 In addition, energy justice scholarship tends to be normative, seeking to identify prevailing injustices and prevent them from being reproduced in ongoing and future energy transitions, thereby providing guides to make “better” energy policy.16 An empirical analysis of historical energy use, however, can reveal the complexities of those questions and the role of historical path dependencies on specific energy technologies like heating equipment or utilities. I therefore propose to look at gender in energy history as an additional analytic category of energy (in)justice – next to distributional, procedural and recognition justice – that mattered and matters for energy constellations and transitions between them.

In this article, I examine the gender and energy justice implications in the changes in residential energy use in Reykjavík from the 1930s to the 1970s. The first part deals with the role of women in Reykjavík before the introduction of geothermal heating. The earlier uses of local biofuels, coal and hot springs for laundry as well as household electrification had many implications for women’s lives and work as housewives and influenced the planning and early development of geothermal heating. The second part deals with the promise of district heating during the 1930s, when a small geothermal utility for public buildings and town houses was constructed, while engineers and municipal politicians planned the construction of a city-wide geothermal utility. Consumers and particularly women played a central role in the discussions about a city-wide utility. Housewives were the ones who handled coal on a daily basis on who the utility promised to relieve, and the utility users had to refund the public investments with their payments for the district heating service. The third part of the article deals with the reality of geothermal heating after the city-wide utility was completed in 1943–1944. Geothermal heating changed much inside the homes and did relieve the housewives, but not necessarily reduce their workload. At the same time, the utility created new injustices between connected and unconnected inhabitants in the new suburbs of Reykjavík, where people continued to use imported fuels for heating. Until the 1970s, the geothermal utility therefore had to be extended to eliminate those injustices, and continued to be framed as a housewives’ cause. Finally, I will explore the question of whether or not the promise of relieving the housewife via an energy transition actually aided the emancipation of women in society.

Back to topThe Gender Implications of Residential Energy Use

The current Icelandic energy reality, with seemingly abundant and cheap heating energy from geothermal and hydroelectric sources, is in stark contrast to the pre-industrial forms of energy use. Iceland has vast hydroelectric resources owing to high precipitation and large glaciers that feed meltwater rivers, as well as hydrothermal resources under the surface owing to the high volcanic activity, which heats up the bedrock and with it the rainwater that seeps into the ground and is turned into hot water and steam. Yet without suitable energy technologies and infrastructures like geothermal wells, electric pumps, hydroelectric power plants or transmission lines, those could rarely be turned into useful energy for the inhabitants. Through most of Iceland’s history, the inhabitants used a variety of locally available solid fuels for their residential energy needs: peat was extracted from local fields; the dung of livestock like sheep and horses was collected and dried; brushwood, shrubs, seaweed, driftwood were gathered and burned; and in some areas also timber from the few forests or lignite coal from a few easily accessible mines.17

Biofuels were the mainstay of the Icelandic fuel economy into the 20th C., when imported coal – superior to Icelandic fuels in terms of energy density – took over as the main household fuel. Before the early 20th C., coal was a luxury fuel that was unaffordable to most Icelanders. Yet when British coal started being imported for steam ships and fish processing, it was likewise widely adopted as a household fuel.18 In 1910, the municipality of Reykjavík also built a coal-based town gas plant and distribution grid, which supplied gas for outdoor and indoor lighting. Town gas predated the electric grid in Reykjavík, as the municipality did not build a centralized grid until the Elliðaár hydroelectric power station went into operation in 1920.19 Town gas was soon marginalized by the electric alternative for lighting, but nevertheless persisted and was used for cooking with gas stoves in the connected households. Gas use in Reykjavík peaked in 1937, when roughly half of all households were connected to the utility,20 while the other half continued to use coal and other solid fuels for cooking stoves.21 For space heating, however, virtually all households used coal and solid fuels, as town gas was rarely used for heating in Reykjavík. By the 1930s, most houses were equipped with water-based central heating systems designed to burn coal, where a coal boiler was usually located in the cellar and hot water distributed through the house’s pipes and radiators, while some older houses still used coal ovens in the apartments.22 In the 1930s, almost all households in Reykjavík therefore relied on coal in one form or another; above all the coal-fired central heating systems that worked poorly with other fuels, but also the many forms of coal or gas stoves and ovens, wherefore coal was the fuel of choice but also mixed with domestic biofuels or whatever paper, wood sticks and household litter there was available.23

For women, most of whom worked as “housewives”, the use of solid fuels meant hard work. It was typically women’s work stoke the ovens and stoves during the day. While coal was considered superior to peat or dung, there was still much work necessary to heat and cook with it. For cooking, the housewife needed to kindle coal in the stove each morning. During the colder months of the year, she also needed to kindle coal for heating. Central heating systems, which had been installed in many homes by the 1930s, changed much in that regard. Instead of burning coal in the kitchen or living room, the fuel was stored in the cellar and shovelled directly into a boiler to heat up water. Coal boilers were perceived as cleaner than ovens, as the coal dust was kept in the cellar, while they increased comfort by saving the housewives the work of carrying coal around the house. Coal stoking nevertheless remained women’s work, as they had to attend to the coal boiler regularly to keep the system running.24

Be it for a stove, oven or boiler, getting coal to burn was everything but easy, as simply lighting matches was usually not enough. The housewife needed to find small sticks, or cleave them from a block of scrap timber, or other easily flammable kindling material like wood shavings or chips to bring the coal to glow. If they had them, they also used newspapers for kindling, or drowned a cloth in kerosene, which many households still kept for (backup) lamps even in the age of electric lighting.25 If the coal chunks were too big, the women had to pound them into smaller pieces with a hammer. And before all that, they had to take out the ashes from the day before and clean out the oven, or else all kindling efforts would be for nothing. If the coal was kept in the cellar but the oven in the upstairs apartment, the women would have to carry the coal along narrow and steep stairways. Heating with coal also meant that homes were notoriously dusty and much women’s work was required to keep them reasonably clean.26 It was women who handled the coal during the day, and it was them who assessed the quality, as apparent from complaints by women to their coal merchants if the coal pieces were too small or too big, or produced too much soot and dust around the house. Coal advertisements therefore addressed the “housemothers” (and not the “housefathers”) when promising to meet their needs for high-quality coal.27

Knowing that Reykjavík is located atop an extinct volcano that still heats up the rock under the city and the water in it might suggest that it was inevitable that the inhabitants would sooner or later tap into that resource. But in reality it was a long process and not necessarily predetermined that the inhabitants would one day use geothermal water instead of fuels for heating. Natural hot springs are quite frequent in Iceland, for instance the springs at Laugarnes around 3 km east of central Reykjavík. The use of geothermal water or steam for space heating, however, required the construction of infrastructures to harness subterraneous hydrothermal reservoirs and distribute the water where it was needed. Many inhabitants were nevertheless users of geothermal energy and had been so for centuries. The hot springs near Reykjavík had been used for bathing and swimming by people living at nearby farms and the village of Reykjavík that took shape from the 18th century. For many women in and around Reykjavík, however, those hot springs were not for bathing but meant hard work. After all, they were not called “bathing springs”, but known as the “Laundry Springs” (Þvottalaugar).28 The “laundry women” (þvottakonur) carried the laundry on their backs or with carriages along the 3 km long “spring path” Laugavegur (today Reykjavík’s main shopping street). There they washed the laundry in a basin with around 80°C hot water, rubbing it on their washboards in between.29 These were both older and younger women who served others by doing laundry for relatively low wages, but also housewives who took their household laundry to the springs themselves. Most of those who did it professionally, however, were older women, who had few other choices of earning a living.30 While some things could obviously be washed with cold water from other sources, the hot springs were essential for sterilizing laundry.31

In the early decades of the 20th C., the act of doing laundry was gradually transferred from the hot springs into the homes, as domestic laundry appliances spread. After freshwater became available from a utility in 1909, many homes in Reykjavík had coal-fired wash pots.32 Those were often replaced with electric wash pots or washing machines from the 1930s, but also washing devices with oil burners in remote areas from the 1940s.33 Despite the spread of washing appliances, many women still used the Laundry Springs, particularly those who could not afford wash pots and the fuel and electricity for them.34 The introduction of washing appliances in the homes saved the housewives of Reykjavík the carrying to the Laundry Springs. Yet it did not mean that the women had no more work with laundry, as coal and electric washing pots were still not automated and required manual work.35 Somewhat paradoxically, the shift from hot spring to indoor laundry meant more work for some housewives, since the profession of laundry women was slowly dying out in the 1940s, and better-off housewives could no longer hire them as easily. The household laundry with washing pots was so much work that some demanded public washing facilities where housewives could have their laundry done for low fees.36

The first infrastructures to utilize the hot spring water beyond bathing and laundry were not in Reykjavík, but by farmers and entrepreneurs in the countryside who laid pipes to use the water for indoor heating and cooking as well as for washing wool.37 Ideas of using the hot springs near Reykjavík were put forward occasionally in the first decades of the 20th C., but concrete plans for district heating infrastructures were not made until 1926, when Icelandic engineers proposed to use the water to heat public buildings and possibly also residential houses.38 To supply more hot water, the engineers started drilling wells around the Laundry Springs in 1928, which were connected to three public buildings – a school, hospital and indoor swimming pool – via a 3 km long pipeline from 1930. Due to the long history of the hot springs’ use for laundry, the experimental utility for the public buildings from 1930 was called the “Laundry Springs Utility”.39 The boreholes were drilled around the two basins with hot water that the women used for washing, and had the effect that the water no longer flowed naturally into the spring, thereby drying up the laundry facility.40 While the lower of the two basins was filled with concrete and no longer used after that, the upper basin was supplied with hot water from the boreholes, allowing the laundry women could continue their work there.41

Meanwhile, the experiment of heating the public buildings with geothermal water was successful. From 1934, the municipality extended the utility to nearby residential houses, which received a connection that allowed them to have geothermal water flow through the houses’ central heating systems. Until 1937, a total of 50 private and 8 public buildings were supplied with geothermal hot water, while the rest of the city’s ca. 3.000 houses continued to be heated with coal. As the existing utility reached its capacity limits and additional wells around the springs did not bring the desired additions, the engineers turned their focus to a much larger geothermal area at Reykir, 15 km outside of the city. Drilling there started in 1933 and soon promised substantially more hot water. The further discussions about district heating were therefore about building a city-wide utility, which required high investments in pipeline and grid infrastructures.42

The planning for a geothermal utility from Reykir, coincided with the construction of a hydroelectric power plant at the Ljósafoss waterfall in the Sog River around 30 km east of Reykjavík, which was built during 1934–1937. The project was intended to provide additional electric capacities for the growing city, and enable the use of electricity for manufacturing and household purposes beyond lighting.43 The discussions about the construction of a large hydroelectric power plant had many implications for Reykjavík households, as well as similarities with the later district heating project. Like heating, cooking and other household tasks were women’s work, and while a wide range of electric appliances would come into focus later on, the discussions in the 1930s concentrated on electric stoves. The promise that proponents of developing the Sog River for Reykjavík made to the housewives was that it would enable them to replace the unpopular coal stoves with electric stoves. In the 1930s, virtually all housewives in Reykjavík used coal for cooking, roughly half in the form of town gas stoves and the other half with coal stoves. As many already used gas for cooking, which was considered much cleaner and higher in comfort than coal stoves, the discussions about the advantages of electricity centred on the dusty, sooty and smoky coal stoves. Electric proponents promised the housewives that once sufficient electricity was available, they could replace the coal stoves with clean and reliable electric stoves. The project’s most vocal opponent, Jónas Jónsson of Hrifla, Minister of Justice and one of the most influential politicians at the time, questioned just that promise. In 1931, his Progressive Party (Framsóknarflokkur) blocked a national government guarantee for the construction loan for the power plant. He did not consider electric stoves necessary: “It is most unlikely, that this question on whether women in Reykjavík would be able to cook with electricity and not with coal, is so important that it requires a 7 million loan with government guarantee.”44 Those comments were later held against him in a caricature, which shows a woman cooking with coal, waiting for that “blessed” electricity to arrive one day (figure 1). The caricature had clear political aims, as it was published by the Conservative Party to highlight the Progressive Party’s opposition at the time, but nevertheless reveals how the unpopularity of coal stoves was reinforced with promises of relieving the housewives with electric stoves.45

The promise to relieve the housewives of their coal stoking duties was one of the main reasons for the broad societal support of the Ljósafoss project. The housewives were also influenced by Reykjavík’s electric utility, as additional residential consumption from cooking was an integral part of the business plan to repay the investment cost for the power plant and transmission system. The boom of electric stoves was also driven by the Icelandic electric equipment producer Rafha and retail salesmen, who promoted the electric stove as cleaner, safer and more convenient for housewives than coal and gas stoves.46 With them, the housewife no longer had to handle coal or kindling sticks. It always worked and obeyed the housewife’s wishes by the turning of a knob, unlike coal fires.47 As it turned out, both those households that used coal stoves and gas stoves almost entirely switched to electric stoves within just a few years after the Ljósafoss plant started supplying electricity in 1937.48

Back to topThe Housewives and the Promise of Geothermal District Heating

Once the Ljósafoss plant was in operation, the city-wide geothermal utility became the most important energy infrastructure project for Reykjavík. In 1937, after four years of exploration, the municipal engineers presented a plan for a utility from the geothermal area at Reykir.49 It envisioned the construction of a 15 km long pipeline and an urban distribution grid to almost all houses in Reykjavík, which at the time was primarily the area within the Ring Road (Hringbraut). Much like with the hydroelectric project, the City of Reykjavík needed foreign know-how, materials and above all a loan in hard currency to implement the geothermal project. The following two years until the utility went into construction in 1939 would therefore mainly consist of a quest for a foreign currency loan and a suitable construction partner.50

To be built, however, the geothermal project needed broad societal support. On the one hand, politicians, engineers and the inhabitants needed to agree on the public expenditures, since the municipal government needed to take up a high loan in foreign currency. On the other hand, the inhabitants needed to be willing to abandon coal and become paying customers of the geothermal utility. It was them who would have to create a return on the investments by paying for the initial house connection and the hot water service according to the utility’s tariffs. The prospective users therefore needed to be convinced both of the feasibility and the desirability of geothermal heating. Acceptance or demand for geothermal heating cannot be assumed a given; particularly not when it meant subordinating to a grid infrastructure, where the users have to trust the operators and the technological infrastructures to provide them with a reliable service. Transitioning from decentral heating with fuel to a centralized form of thermal energy distribution involved a major change for energy users. They had to be assured that the utility would provide them with comparable or better heating than if they continued to burn coal themselves.51

The proponents of geothermal heating – mainly politicians and engineers – promised that it would liberate the inhabitants from their dependency on dirty and expensive coal. Given that coal meant soot, dust and ash, geothermal heating was framed as a clean and smokeless alternative.52 Proponents praised the project as an effort to make Reykjavík the cleanest and most liveable city in the world, without chimneys, soot and smoke.53 It would also save the inhabitants millions of Icelandic kronas in foreign currency spending for imported coal, thereby liberating them from the uncertainty stemming from currency exchange rates. With widespread fears of coal supply disruptions in case of a new world war in the 1930s, the geothermal alternative was valued for the energy independence it promised.54 The promise of equal access to reliable and affordable heating was especially popular with the poorer inhabitants of Reykjavík. The city’s political Left therefore embraced district heating as a social justice issue during the 1930s and blamed the ruling Conservatives (who originally made geothermal heating a prestige project) for not building the city-wide utility.55 District heating was expected to eliminate prevailing energy injustices related to coal,56 as residential heating had become less affordable for working class households due to rising coal prices during the 1930s, causing many to despise coal merchants for their price policies. Geothermal heating would make adequate indoor heating affordable for everyone.57 Owing to those high expectations, constructing a geothermal utility for the entire city became the prestige project, which both camps in municipal politics blamed each other for blocking or not implementing.58

The proponents of geothermal heating, particularly from the Conservatives, went beyond praising geothermal heating as a clean and cheap energy alternative. Similar to the promise of electricity just years earlier, they specifically addressed the female inhabitants and framed it as a “housemothers’ cause”. As with the demand for energy alternatives in general, women’s demand for or even acceptance of a new form of energy distribution could not be taken for granted at the time (and should not be assumed a given by historians either). The housewives’ overwhelming support was created in the context of the debates about a city-wide geothermal utility in the 1930s. Since it was typically housewives who had to stoke the coal ovens, the geothermal alternative was framed as a housewives’ cause.59 In a 1938 political campaign depiction, handling the coal oven is portrayed as dark, sooty, dusty and labour-intensive for the housewife. With district heating, which is portrayed as bright and blue, the housewife would only have to regulate the radiators and could devote her time and energy to other tasks, like cooking or cultivating exotic fruits, flowers and vegetables in geothermally heated greenhouses (figure 2).

One of the most vocal public proponents of district heating was the women’s organization of the conservative Independence Party (Sjálfstæðisflokkur). As prominent female party soldier Soffía M. Ólafsdóttir put it in 1938: “The heating utility is the housemothers’ cause.” Aiming to mobilize housewives to vote for the Conservatives in the 1938 municipal elections, she argued that the geothermal utility would change most for the poorer housemothers who had to carry coal over longer distances to get them into the oven. In those households, Soffía asserted, the utility would not only save money and the arduous work and trouble with coal, but also shorten housewives’ working days. It would make their household heating and cleaning tasks much easier, both because there was less dust and dirt, and because they would always have hot water available. In the conclusion of her 1938 article, she condemned the Leftists for their alternative proposals that she believed sabotaged the project, making it clear that housewives should only trust her Independence Party to build the geothermal utility.60

The debate about the advantages of district heating for women went beyond the mentioned political campaigns in relation with the 1938 municipal elections. Many women replicated the promise of everything becoming better in Reykjavík when the geothermal utility would be built. This can clearly be seen in contemporary articles in the New Women’s Magazine (Nýja kvennablaðið). In 1942, a woman by the name of María J. Knudsen wrote about her high expectations of the heating utility. The hot water would heat the homes, banish the coal smoke and clear the air, and put an end to all the work and dust of handling coal and ash. It would mean no less than “enormous work reductions and comforts”, and in fact amount to a “revolution of household work”.61 Many others saw the advantage for housewives to always have hot or warm water ready on tap whenever it was needed to clean around the house.62 In 1944, an unknown woman wrote to the magazine and expressed how much she was looking forward to geothermal Reykjavík. She found it exiting how the hot water would just flow into the houses, clean and clear. All the dirt from coal would vanish, and with it the coldness in the homes. She even speculated about the effect on humans in general: “Whether we would not also become better humans too?”63

Overall, the housewives of Reykjavík were an essential part of the city’s inhabitants – both as consumers and voters – who had to be convinced for the district heating project to be implemented. They were in charge of coal stoking and key to condemning coal and creating a societal demand for the geothermal alternative. While it was often their husbands who earned the household income, and thereby provided the funds to repay the city’s investments through utility payments, women were the ones handling the coal during the day and had strong influence on household decisions. There is little evidence of husbands opposing the geothermal cause simply because it aided their housewives. By the time the City of Reykjavík obtained a foreign currency loan from the Danish Handelsbanken and partnered with the Copenhagen contracting firm Højgaard & Schultz to build the utility in 1939, there was overwhelming public support for the project. While the construction process was complicated and delayed by the events of the Second World War, the utility could nevertheless be completed in 1943–1944 (figure 3). Thereby, around 3.000 buildings received a connection, and soon thereafter the first utility bills to help repay for the investments.64

The Reality of Geothermal District Heating

With houses connected to the geothermal grid, coal heating was indeed eliminated as the main form of heating in the utility area, and with it – at least at first sight – the fuel poverty and gender injustices that stemmed from the use of imported coal. Yet the historical reality was more complicated. Connecting to the heating grid meant major changes for energy consumers, as they transitioned from burning fuel individually to consuming heat from the utility. This socio-technical context of connecting to geothermal heating is essential to assess inasmuch the new system eliminated or reproduced prevailing injustices. In theory, district heating created a high potential for equalizing the distribution injustices and fuel poverty found in fuel-based individual heating. It also meant the end of housewives’ chores attached to individual heating with coal, as it had generally been the housewives’ responsibility to stoke the coal ovens to keep houses warm. How did that work out in reality in Reykjavík?

The geothermal utility did indeed relieve the housewives in connected houses of their coal stoking responsibilities. Keeping dwellings warm henceforth only involved regulating the radiators to control the hot water flow. Most households had transitioned directly from central heating with coal boilers to district heating, wherefore the geothermal hot water was simply pumped into the pre-installed coal-based heating system. Many still had functioning coal boilers when connecting to the heating utility. Some of those were kept and maintained as a backup heating option, others were disassembled and some just left to rust as the years went by.65 Those households that decided to keep coal as a backup fuel could put them to good use, as the geothermal utility frequently failed during cold spells in the early years. Most days in the year, the utility worked, but when temperatures dropped too far, it tended to fail, as the hot water storage tanks were depleted and took time to fill up again. When that happened, the housewives called the utility director “frost man” (kuldaboli).66 To prevent such cold spell failures, the utility started using oil-fired heating plants from 1948 to increase the temperature of the geothermal water when needed.67

Apart from those coldest days, however, the utility provided a reliable hot water service, which the housewives used both for the heating of their homes and a variety of other household uses. The work day changed as the housewives no longer needed to worry about stoking coal, but they had to find solutions to work with the mineral-rich hot water that came out of their taps. Particularly silver cutlery and jewellery had to be treated with care. Many had to find out in an unpleasant manner that the geothermal water damaged the silver coating of their fine Sunday dining cutlery. The only solution was to clean the silver cutlery with heated freshwater instead, as one housewife advised others in 1951.68 With hot water always readily available on tap, many housewives were inclined to use the geothermal water also for tea and coffee. While opinions on that were divided – the geothermal water did have a slight but noticeable sulfuric smell to it – many did drink and cook with the utility water. The utility even encouraged people to drink and cook with the geothermal water, as it was classified as harmless and even healthy because it contained fluorine, which was said to strengthen the kids’ teeth.69 Those views towards the healthiness of geothermal water changed in the 1990s, as slight but traceable contents of heavy metals and potentially harmful concentrations of fluorine were discovered. Since the problematic minerals could not be filtered out of the water easily, the inhabitants were discouraged from drinking the geothermal water that came directly from the boreholes. From the 1990s, however, most of the utility started being supplied with geothermally heated freshwater, which made the utility water harmless again.70

The utility changed much for the housewives regarding bathing water. As mentioned, most homes already had central heating systems with coal boilers in which water could be heated for bathing, but depending on the size of those boilers, that water was limited as well as expensive. Some homes also still had kitchen stoves with small boilers for bathing water, or no central heating system at all. For the housewives, having steady and reliable hot water from the utility meant that they no longer had to worry about the availability and cost of bathing water. In the long run, the ample availability of hot water led to a culture of hot water abundance, as long showers, warm apartments and running hot water became negligible household expenses.71 For the average household in the utility area, it did bring significant savings. The inhabitants also felt healthier due to less respiratory irritation from coal smoke and fewer colds, which were associated with more reliable indoor heating. The general perception that people got healthier with district heating is reflected in health statistics, which – coincidentally or not – reveal significantly lower rates of colds in Reykjavík from 1943, while those in the rest of the country remained similar.72

The geothermal water was used for cleaning around the house and for (manual) dishwashing, which many started doing under running hot water, as there were few reasons to save the hot water anymore. Reykjavík’s housewives also used the readily available utility water for handwashing the household laundry. For the big laundry days, however, they did not shift to the geothermal alternative, but continued to use coal, oil or electricity-based washing pots. In those pots, using the already hot utility water was not considered an issue, as the minerals in the water did not damage the pots.73 As for the automated washing machines, which became common from the 1960s, most used freshwater, since the geothermal water could cause clogging or damages due to the minerals.74 With most households having washing pots and some already washing machines, the Laundry Springs – by then within the city – were no longer essential to housewives. They nevertheless continued to be used into the district heating age, especially by women from the unconnected outer districts of the city, and remained open for housewives to do their laundry into the 1970s.75

District heating, however, did not only have advantages for the housewives. The end of coal-firing created a new problem: what to do with all the trash? While few missed handling coal and ash, many did miss the fire, as they could no longer burn the household waste. Now the waste bins, then still called “ash bins” (öskutunnur), were no longer filled with ash but overfilled with trash. Instead of coal smoke, the inhabitants now had to endure the foul smell of rotting food scraps, which the lids of the overfilled bins could not contain.76 What had never been an issue while all houses had coal fires became a problem that the public authorities had to deal with. A woman named Sigríður Arnlaugsdóttir proposed to build chicken stables all over town to put the food scraps to good use and receive eggs in return.77 Yet this common practice on farms rarely became the reality in urban Reykjavík, as the authorities found solutions with larger trash bins.

Overall, the heating utility did relieve the housewives of their coal stoking tasks and the readily available hot water brought several other advantages for household work. Regarding the societal role of the housewife, however, the heating transition changed little existential, as it was not like there was no more work for the housewife. Instead, it resulted in shifting tasks within the home, thereby reproducing the prevailing gender roles of working males and stay-at-home females. With geothermal heating, housewives had more time to focus on other tasks like cooking, washing and cleaning – just as promised in the 1938 advertisement depicted above (figure 2). Similar to electric household technologies, the innovations in heating had a revolutionary effect on the work of the housewife, but not on the role of the housewife itself. The societal gender injustices, above all unequal pay and unequal access to education and waged labour, remained and were not eradicated by electric appliances or district heating alone.

District heating could, on the other hand, resolve the energy injustices among those living in the utility area. Yet it also created new distribution injustices between those who were connected to the grid, and those who were not. In the 1930s, the utility had been planned for all inhabitants of Reykjavík, who mainly lived within the Ring Road, but not the new districts that spread outside of this area during and after the Second World War.78 As a result, the geothermal utility soon excluded almost half of the city’s inhabitants in the new and growing suburbs, as only 55 % of the city’s dwellings received district heating in 1950 and still only 53 % in 1960 – and that despite the number of connected dwellings having increased from 7.025 to 9.437 in 1960 (figure 4).

In those suburbs, like in most other areas of Iceland, coal was replaced with oil. Already before the 1940s, small kerosene ovens had been used to heat individual rooms or as a backup heating option.79 Most oil heating systems installed from the mid-1940s, however, were central heating systems. Oil was stored in a tank and pumped automatically into a burner and water boiler, from where it was circulated through pipes and radiators.80 Already by 1950, more than half of Reykjavík’s fuel-heating households used oil-fired central heating (figure 4).81 Soon after the city-wide geothermal utility went into service, there were thousands of people living right next to it in the new suburbs, who continued to rely on imported fuels for heating.82 Unlike coal, automated oil heating offered similar advantages in terms of comfort and cleanliness as geothermal district heating. The thermostat took over the labour of adding fuel to regulate the temperature and resulted in less heating-related work for the housewife.83 The smoke was not as black and there was no soot, ash and dust left inside the house. Oil was fluid and had a higher carbon concentration and therefore energy density, which meant it required less space in transportation and storage than coal.84 Like with electric appliances and district heating, advertisements for oil heating were made with the coal-stoking tasks of housewives in mind, promising them unprecedented comforts. A 1946 advertisement for oil heating communicated the advantages as follows: “Why does everybody choose automated oil heating? It is clean; it is smoke-free, it is balanced and healthy, it is cheapest. It saves much work, it saves trips down to the cellar, it saves coal shovelling, it saves ash carrying, it saves coal storage room, it lowers the danger of fire.”85

Given the higher cost of fuel heating compared to the geothermal utility, the inhabitants of unconnected districts complained about the situation and petitioned to receive access. They lamented that the utility created unequal living standards for the inhabitants because connected households enjoyed better and cheaper heating.86 It was particularly from those unconnected suburbs that housewives would continue to use the Laundry Springs. The question for the utility managers was not if, but how and when the grid would be extended to the new districts. But since it was unrealistic to extend it to all at once, the closest districts to the present utility area in the Western half of the city were connected first (Melar and Hlíðar). Yet as the disparity between East and West in Reykjavík became ever more apparent, the politicians from Left and Right made “district heating for everyone” political campaign material and extending it became a prestige project for mayor Gunnar Thoroddsen (1947–1959) and his successor Geir Hallgrímsson (1959–1972).87

In the course of the 1960s, the unconnected districts of Reykjavík were gradually integrated in the utility grid, primarily funded with a World Bank loan from 1960. The extension could be implemented with additional drilling for hot water, efficiency improvements in the present production and distribution systems, and the strategic use of oil-fired heat plants to provide backup heating during cold spells. Owing to the extension of the utility grid during the 1960s, the number of geothermal users increased by around 30.000 to 74.000 by 1970, when only 4.000 inhabitants remained unconnected.88 Yet while the disparity within Reykjavík grew less apparent, that within the greater Capital Area – by then seven municipalities that had practically grown together – became ever more apparent. Given that in 1970, the cost of heating from the utility in Reykjavík was only about half of what other inhabitants paid for electric or oil heating, there was much dissatisfaction among the inhabitants who remained unconnected.89 For this reason, the governments of the seven municipalities established a joint committee in 1969 to plan for the extension of Reykjavík’s heating utility to the entire Capital Area. While already prepared before, the extension was accelerated by the oil price increases from late 1973, which served as a powerful economic incentive to extend the utility as quickly as possible, since all involved assumed that oil prices would not decrease again in the near future.90 Until 1979, all suburbs and neighbouring towns of Reykjavík – particularly the towns of Kópavogur and Hafnarfjörður – were integrated in one large geothermal utility for the Capital Area.91 Already from 1976, most inhabitants in the Capital Area (92.5 % in 1976) enjoyed the comforts and the economic savings of geothermal district heating.92 Thereby, distribution injustices within Reykjavík and the greater urban area were eliminated, and with it the fuel poverty associated with decentral coal and oil heating.

During all this time, geothermal heating continued to be framed not only as a social justice issue but also as a housewives’ cause. As the ones who managed household work, women remained vocal proponents of extending the geothermal utility to the suburbs. It would improve their lives and lower household spending, even though it involved few actual changes for the housewife in terms of labour associated with space heating, as most unconnected houses were already heated with automated oil systems. In unconnected Hafnarfjörður, for instance, a local woman once called district heating the “dearest dream of all housewives”, which would increase comfort and liberate them from having to attend the fires of their heating systems.93 The promise to the “housemothers” can also be seen in a representation of two women inspecting the new pipeline being laid to their borough at Otrateigur in Eastern Reykjavík in 1962 (figure 5). The article included a calculation that district heating for an exemplary apartment only cost half as much as oil heating (3.800 kronas compared to 7.000), which was considered a blessing for the housewives of Reykjavík.94

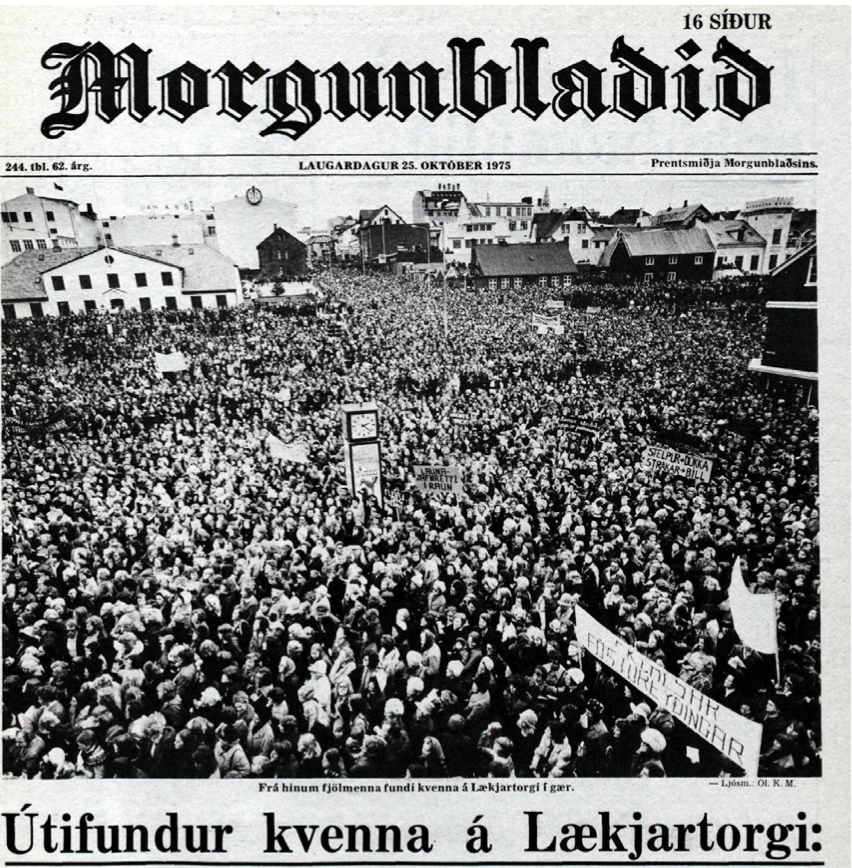

In the end, the socio-technical changes in the Reykjavík heating sector, with the transition from decentral heating with coal to geothermal heating, and the shifts from coal to oil in unconnected suburbs and later to geothermal heating, did relieve the housewives as promised. Yet the new forms of heating ended up reproducing the prevailing gender roles. While it would be compelling to attribute Iceland’s high level of gender equality to the introduction of geothermal heating, the historical evidence suggests otherwise. With regard to geothermal heating, women had important roles as consumers as well as voters, but those roles need to be distinguished from their roles as citizens struggling for societal emancipation. The societal roles of women were not changed by heating technologies, but by political activism of the women’s movement. Particularly from the mid-1970s, the Icelandic women’s movement had brought about many advances for women’s rights with iconic protests like the “Women’s day off” (Kvennafrídagurinn) first held on 24 October 1975, where an estimated 90 percent of the female population went on strike for the day and turned out at public protests against unequal pay.95 On that Friday in late fall, thousands of women (as well as men) left their comfortable, geothermally heated homes and went to the smoke-free city centre of Reykjavík to demand equal pay and rights for women, which helped Iceland becoming a model country in gender equality over the following decades (figure 6).

Conclusion

This article set out to examine the gender and energy justice implications of geothermal district heating in Reykjavík. Starting as an experiment with public buildings in the 1930s, geothermal heating became the primary form of heating with the construction of a utility for the central districts in 1939–1944, which was gradually extended to the suburbs until the 1970s. The adoption of geothermal district heating entailed a shift from decentral heating with fuels to a centralized form of heat distribution. Handling fuel around the house for heating, cooking, and washing – be it with coal, peat or other biofuels – had typically been the responsibility of the housewives. Similarly, the washing of laundry in the hot springs of Reykjavík had been women’s work. It was therefore crucial for the proponents of geothermal heating, and similarly for those of large-scale electrification, to promise to relieve the housewives of their coal stoking duties and frame the geothermal project as a housewives’ cause. To understand the history of the adoption of geothermal heating in Reykjavík, it is necessary to examine gender relations and injustices linked to the use of energy. Women not only mattered as consumers of energy, but also as voters and as managers of household energy use, whose negative views of handling coal and other fuels aided the transition to the geothermal alternative. They needed to be convinced of the geothermal cause, which depended on broad public acceptance and support to refund investments with utility payments.

The long-term view on the gender and energy justice implications of residential energy use, however, reveals a divergence between the promise and the reality of geothermal heating. The adoption of geothermal heating indeed changed many things for the housewives. They no longer needed to handle coal and could use the hot water for a variety of household tasks. Yet it also created new problems. Silver cutlery could be damaged by geothermal water and household waste could no longer be burned. And while district heating eliminated energy injustices related to the use of fuels in the utility area, it created new injustices between connected and unconnected districts (and housewives). Those injustices could only be overcome with the gradual extension of the utility to the suburbs between the 1950s and 1970s. Reykjavík’s adoption of geothermal heating therefore had many implications for women and did relieve them in their work. Yet it did not by itself amount to a societal liberation of housewives. Geothermal heating did not revolutionize their societal roles but rather reproduced prevailing gender relationships. Housewives remained housewives, and the comforts of geothermal heating did not necessarily reduce the overall workload inside the home. The roles of women as consumers and voters, by which they influenced the geothermal history, need to be distinguished from their role as citizens striving for emancipation. Iceland becoming a model country for gender equality was the result of a broader societal process. Still, gender relations did play an important role in the history of geothermal heating that must not be overlooked.

- 1. On the cases of New York and Copenhagen, see: “The Distribution of Light and Heat in New York City”, Scientific American, vol. 45, n° 21, 1881, 319–320; A.K. Bak, Johannes Hansen, “District Heating in Copenhagen”, District Heating, vol. 44, n° 4, 1959, 143–147.

- 2. Euroheat and Power, “Statistical Overview: TOP District Heating and Cooling Indicators 2013”, euroheat.org, 03/2016. Url: http://www.euroheat.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/2015-Country-by-coun… (accessed 06/07/2021). For an international comparison, see Sven Werner, “International Review of District Heating and Cooling”, Energy, vol. 137, n° 15, 2017, 617–631.

- 3. For an overview, see Svend Frederiksen, District Heating and Cooling (Lund: Studentlitteratur, 2013).

- 4. The most commonly used terms were “housemother” next to “húsfrú” (house-wife) or “húsfreyja” (house-keeper/mistress).

- 5. For current numbers, see: Orkustofnun, Húshitun eftir orkugjafa, OS-2018-T010-02 (Dataset, 2018). In terms of total heated space in 2016, 89,2 % were heated with geothermal district heating, 3,6 % with district heating based on electric/oil-fired heat plants, 7% with electricity, and 0,2 % with oil. On electricity production, see Orkustofnun, Uppsett rafafl og raforkuframleiðsla í virkjunum á Íslandi, OS-2019-T006-01 (Dataset, 2019).

- 6. See a 2016 comparison of utility heating costs: Samorka, “Húshitunarkostnaður langlægstur í Reykjavík”, samorka.is, 16/08/2016. Url: https://www.samorka.is/hushitunarkostnadur-langlaegstur-i-reykjavik/ (accessed 06/07/2021).

- 7. See e.g. Ingimar G. Haraldsson, Þóra H. Þórisdóttir and Jónas Ketilsson, Efnahagslegur samanburður húshitunar með jarðhita og olíu árin 1970–2009 (Reykjavík: Orkustofnun, 2010).

- 8. For an overview, see: Erla Hulda Halldórsdóttir et al., Konur sem kjósa: aldarsaga (Reykjavík: Sögufélag, 2020).

- 9. See e.g. the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index: Magnea Marínósdóttir, Rósa Erlingsdóttir, “This Is Why Iceland Ranks First for Gender Equality”, weforum.org, 01/11/2017. Url: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/11/why-iceland-ranks-first-gender-e… (accessed 06/07/2021).

- 10. For instance Lýður Björnsson, Saga Hitaveitu Reykjavíkur 1928–1998 (Reykjavík: Orkuveita Reykjavíkur, 2007). One of the few comprehensive studies of the socio-technical making of a district heating utility can be found in Jane Summerton, District Heating Comes to Town: The Social Shaping of an Energy System (Linköping: Linköpings universitet, 1996).

- 11. Beyond historiography, geothermal energy and district heating have been examined in energy studies and engineering sciences, albeit often with a contemporary viewpoint or a mainly documentary approach to including historical “backgrounds”, which has rarely engaged with the role of geothermal consumers or gender relations. See e.g. the recent edited volume on geothermal “energy and society”, which deals with many aspects of energy use but only marginally looks at consumers or gender aspects: Adele Manzella, Agnes Allansdottir, Anna Pellizzone (eds.), Geothermal Energy and Society (Cham: Springer, 2019).

- 12. To name a few: Ruth Cowan, More Work for Mother: The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Hearth to the Microwave (New York: Basic Books, 1983); Shelley Nickles, “‘Preserving Women’: Refrigerator Design as Social Process in the 1930s”, Technology and Culture, vol. 43, n° 3, 2002, 693–727; Karin Zachmann, “A Socialist Consumption Junction: Debating the Mechanization of Housework in East Germany, 1956–1957”, Technology and Culture, vol. 43, n° 1, 2002, 73–99; Graeme Gooday, Domesticating Electricity: Technology, Uncertainty and Gender, 1880–1914 (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2008); Sophie Gerber, Küche, Kühlschrank, Kilowatt: Zur Geschichte des privaten Energiekonsums in Deutschland, 1945–1990 (Bielefeld: Transcript, 2015); Vanessa Taylor, Heather Chappells (eds.), “Energizing the Spaces of Everyday Life: Learning from the Past for a Sustainable Future”, Special Issue of RCC Perspectives, n° 2, 2019; Abigail Harrison Moore and Ruth Sandwell (eds.), “Women and Energy”, Special Issue of RCC Perspectives, n° 1, 2020; and most recently: Abigail Harrison Moore and Ruth W. Sandwell, In a New Light: Histories of Women and Energy (Montreal et al.: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2021).

- 13. See particularly on the three “tenets” of energy justice (distributional, procedural and recognition justice): Kirsten Jenkins, Darren McCauley, Raphael Heffron, Hannes Stephan, Robert Rehner, “Energy Justice: A Conceptual Review”, Energy Research & Social Science, n° 11, 2016, 174–182; Darren McCauley, Raphael Heffron, Hannes Stephan, Kirsten Jenkins, “Advancing Energy Justice: The Triumvirate of Tenets”, International Energy Law Review, n° 32, 2013, 107–110.

- 14. Jenkins et al. see gender differences as a “recognition justice” issue, as certain societal groups are underrepresented in energy decision making: Jenkins et al., “Energy Justice”, 177–178. Cherp et al. similarly acknowledge “entrenched gender bias” as a justice issue in energy decision making: Aleh Cherp, Vadim Vinichenkoa, Elina Brutschin Benjamin Sovacool, “Integrating Techno-Economic, Socio-Technical and Political Perspectives on National Energy Transitions: A Meta-Theoretical Framework”, Energy Research & Social Science, n° 37, 2018, 175–190. The unequal effect of “energy poverty” on men and women has also been documented by the UN and several scholars: Benjamin K. Sovacool, Matthew Burke, Lucy Baker, Chaitanya Kumar Kotikalapudi, Holle Wlokas, “New Frontiers and Conceptual Frameworks for Energy Justice”, Energy Policy, n° 105, 2017, 677–691, here 588. For a study with a focus on gendered geographies, see: Susan Buckingham, Rakibe Kulcur, “Gendered Geographies of Environmental Injustice”, Antipode, vol. 41, n° 4, 2009, 659–683.

- 15. For a study of Eastern European energy poverty and district heating, see: Sergio Tirado Herrero, Diana Ürge-Vorsatz, “Trapped in the Heat: A Post-Communist Type of Fuel Poverty”, Energy Policy, n° 49, 2012, 60–68. In most studies of energy justice, however, district heating is little more than a side note. See e.g. Michael Carnegie LaBelle, “In Pursuit of Energy Justice”, Energy Policy, n° 107, 2017, 615–620, here 618.

- 16. Jenkins et al., “Energy Justice”, 174–182; Raphael J. Heffron, Darren McCauley, “The Concept of Energy Justice across the Disciplines”, Energy Policy, n° 105, 2017, 658–667.

- 17. Ian A. Simpson, Orri Vésteinsson, W. Paul Adderley, Thomas H. McGovern, “Fuel Resource Utilisation in Landscapes of Settlement”, Journal of Archaeological Science, n° 30, 2003, 1401–1420; Gunnar Bjarnason, “Höfum við gengið til góðs”, Búfræðingurinn, vol. 14, n° 1, 1948, 106–119, here 108–109.

- 18. Helgi Skúli Kjartansson, Halldór Bjarnason, “Fríhöndlun og frelsi, 1830–1914”, in Sumarliði Ísleifsson (ed.), Líftaug landsins – saga íslenskrar utanlandsverslunar 900–2010 II (Reykjavík: Skrudda, 2017), 11–109, here 70–71.

- 19. Stefán Pálsson, “Af þjóðlegum orkugjöfum og óþjóðlegum: Nauðhyggja í íslenskri orkusögu”, in Erla Hulda Halldórsdóttir (ed.), 2. íslenska söguþingið 2002 (Reykjavík: Sagnfræðistofnun Háskóla Íslands & Sagnfræðingafélag Íslands, 2002), 254–267.

- 20. “Gasstöðin hefir kol í 25 daga: 4462 heimili í bænum nota gas til suðu”, Vísir, 28/09/1937, 3.

- 21. Guðjón Friðriksson, Saga Reykjavíkur: Bærinn vaknar, 1870–1940 I–II (Reykjavík: Iðunn, 1991–1994), 381–383.

- 22. See the census data on household amenities for 1940 in Hagskýrslur um húsnæðismál, 1950, 59.

- 23. See numerous references to the use of multiple fuels even in central heating systems in the following questionnaire by the Icelandic National Museum (Þjóðminjasafn Íslands): Spurningaskrá 117: Híbili, húsbúnaður og hversdagslíf.

- 24. For a detailed description of women’s kindling and stoking tasks, see: Anna Sigurðardóttir, Störf kvenna í 1100 ár (Reykjavík: Kvennasögusafn Íslands, 1985), 98–99. Sometimes the husbands help cleaving coal or the kindling sticks, but attending to the fire was mainly women’s work.

- 25. On the use of kerosene to incinerate coal, see: Jón Þ. Þór, Svartagull: Olíufélagið hf. 1946–1996 (Reykjavík: Olíufélagið, 1996), 56.

- 26. Kristín Marselíusardóttir, ’Ég hef engan svikið með mínum verkum, allt var þetta skóli’: Vinnukonur í þéttbýli á 2.–4. áratug 20. aldar (BA thesis, University of Iceland, 2019), 16.

- 27. See e.g. “K-O-L”, Verkamaðurinn, n° 18, 1928, 4.

- 28. Sveinn Þórðarson, Auður úr iðrum jarðar: saga hitaveitna og jarðhitanýtingar á Íslandi (Reykjavík: Hið íslenska bókmenntafélag, 1998), 81–87 and 94–112.

- 29. Óskar Guðmundsson, “Þvottalaugarnar í Laugardal”, Þjóðlíf, n° 9, 1990, 58–59; Gyða Gunnarsdóttir, “Þarna var einu sinni líf í tuskunum”, Vera, n° 2, 1986, 20–21.

- 30. On the use of hot springs and laundry women, see: Þórðarson, Auður úr iðrum jarðar, 98–112; Sigurðardóttir, Störf kvenna í 1100 ár, 67–84.

- 31. Margrét Gunnarsdóttir, “Þvottalaugarnar í Reykjavík: heilsulind Reykvíking”, Vera, n° 4, 1995, 14–15.

- 32. See frequent references to washing pots in the following questionnaire: Icelandic National Museum, Spurningaskrá 64: Hreingerningar og þvottur.

- 33. On electric washing machines, see: Sigrún Pálsdóttir, “Húsmæður og haftasamfélag: Hvað var á boðstólum í verslunum Reykjavíkur á árunum 1947 til 1950?”, Sagnir, n° 12, 1991, 50–57, here 56. On coal and oil pots, see several references in this questionnaire: Icelandic National Museum, Spurningaskrá 117 Híbili, húsbúnaður og hversdagslíf; and advertisements like “Sparnaðar-Þvottapottur”, Fálkinn, n° 20, 1934, 20.

- 34. “Þvottalaugarnar”, Fálkinn, n° 34, 1934, 1.

- 35. Husbands sometimes offered a helping hand on the big laundry days once or twice a month, see the account of a woman (b. 1947) from Reykjavík, in the following questionnaire: Icelandic National Museum, Spurningaskrá 122: Aðstæður kynjanna.

- 36. María J. Knudsen, “Almenningsþvottahús”, Nýtt kvennablað, n° 5–6, 1942, 1–3.

- 37. Benedikt Gröndal, “Hagnýting á hveraorku”, Tímarit VFÍ, vol. 13, n° 4, 1928, 33–35.

- 38. See the lectures published in Tímarit VFÍ, vol. 11, n° 6, 1926.

- 39. Hitaveitan frá Þvottalaugunum, or in short Laugaveitan.

- 40. “Hneyksli, sem aldrei var afhjúpað”, Alþýðublaðið, 17/07/1933, 2.

- 41. Þórðarson, Auður úr iðrum jarðar, 106–107.

- 42. Skýrslur og áætlanir um Hitaveitu Reykjavíkur (Reykjavík: Hitaveita Reykjavíkur, 1937).

- 43. Steingrímur Jónsson, “Sogsvirkjunin”, Tímarit VFÍ vol. 23, n° 3, 1938, 21–50.

- 44. See the comments by Jónas Jónsson in Alþingistíðindi, 44. þing (aukaþing), C, Umræður um fallin mál á aukaþingi, 1931, 355: “Það er í mesta máta óliklegt, að þetta spursmál um það, hvort konur í Reykjavík geti soðið við rafmagn, en ekki við kol, sé svo stórt, að það þurfi að taka 7 millj. að láni með ríkisábyrgð.”

- 45. Sumarliði Ísleifsson, Í straumsamband: Rafmagnsveita Reykjavíkur 75 ára (Reykjavík: Rafmagnsveita Reykjavíkur, 1996), 80.

- 46. See advertisements for electric stoves: “Það getur sparað yður stúlku”, Sjómannadagsblaðið, n° 1, 1939, 10; “Ný tegund af rafsuðuvélum”, Alþýðublaðið, 30/04/1932, 3. See also numerous references to domestically produced electric appliances by Rafha in the following questionnaire: Icelandic National Museum, Spurningaskrá 96, Rafvæðingin I. Þegar rafmagnið kom.

- 47. See e.g. an advertisement: “Langþráð ósk, sem loks er að rætast”, Siglfirðingur, n° 26, 1936, 4. On the popularity of household appliances among Reykjavík’s housewives, see also: Nanna Ólafsdóttir, “Húsmæðurnar og miljónin og atkvæðin”, Melkorka, vol. 5, n° 2, 1949, 67–69.

- 48. Árni Óla, “Úr sögu Reykjavíkur: Gasstöðin kveður”, Lesbók Morgunblaðsins, 27/04/1958, 217–223. Ísleifsson, Í straumsamband, 143–153.

- 49. Skýrslur og áætlanir um Hitaveitu Reykjavíkur.

- 50. Lýður Björnsson, “Í lánsfjárleit 1937–1939”, SAGA, n° 28, 1990, 63–85.

- 51. For a detailed discussion on the creation of user demand, see Odinn Melsted, “Who Generates Demand for Sustainability Transitions? Geothermal Heating in Reykjavík”, RCC Perspectives, n° 2 (2019), 31–38. The argumentation that builders of infrastructures have to help create demand for the energy alternatives draws from Christopher Jones, Routes of Power: Energy and Modern America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014), 232.

- 52. “Reyklausi bærinn”, Morgunblaðið, 28/12/1943, 6.

- 53. Árni Óla, “Hitaveita Reykjavíkur“, Lesbók Morgunblaðsins, 07/06/1936, 177–181.

- 54. There were debates about whether Reykjavík should shift from coal to electric heating instead. Electric heating offered similar benefits over coal as a locally available and smokeless alternative, and did not require additional investments in transmission infrastructures. Yet proponents of geothermal heating succeeded with their argument that it would be more efficient and cheaper than electric heating in the long run. See the most vocal electric proponent: Sigurður Jónasson, “Hitun Reykjavíkur”, Nýja dagblaðið, 21/08/1938, 1 and 4, and (cont.) 26/08/1938, 1 and 4.

- 55. For the Leftist position, see: “Hitaveitan á að vera þjóðþrifamál”, Þjóðviljinn, 07/12/1937, 3; “Hvenær kemur hitaveitan?”, Verkalýðsblaðið, vol. 7, n° 29, 1936, 4.

- 56. On fuel poverty issues in heating, see e.g. LaBelle, “In Pursuit of Energy Justice”, 618.

- 57. “Kolahækkunin er hrein okurtilraun af hálfu verzlanna”, Alþýðublaðið, 30/07/1937, 1.

- 58. “Hitaveitan á að vera þjóðþrifamál”, 3.

- 59. Soffía M. Ólafsdóttir, “Hitaveitan er málefni húsmæðranna”, Morgunblaðið, 21/01/1938, 6.

- 60. Ólafsdóttir, “Hitaveitan er málefni húsmæðranna”, 6.

- 61. Knudsen, “Almenningsþvottahús”, 1–3: “Og nú síðast eigum við von á hitaveitunni, heitu vatni, sem hitar upp híbýli okkar, svo að við ekki þurfum að basla með kol og ösku, reykurinn hverfur úr bænum, en loftið verður hreint og tært. Þetta allt er geysilegur vinnusparnaður og þægindi, og svo mikil bylting á heimilisháttum, að þeir, sem ekki þekkja annað en nútímann, munu vart geta skilið þann mun.”

- 62. “Hitaveitan”, Morgunblaðið, 02/07/1933, 3.

- 63. “Úr öðru bréfi”, Nýtt kvennablað, n° 4, 1944, 12: “Ætli við hljótum ekki að verða betri menn líka?”

- 64. Björnsson, Saga Hitaveitu Reykjavíkur, 79–139. For a technical description, see Sigurðsson, “Hitaveita Reykjavíkur”, 26–39.

- 65. For accounts on coal heating being kept as a backup, see the following questionnaire, particularly the account of a woman (b. 1938): Icelandic National Museum, Spurningaskrá 117: Híbili, húsbúnaður og hversdagslíf: woman (b. 1938), 191.

- 66. For references to “kulaboli” see e.g.: “Á föstu kaupi”, Morgunblaðið, 27/02/1966, 4; “Reykjavík mótmælir! Þolir hitaveitan ekki nema 6 stiga frost?”, Alþýðublaðið, 08/12/1967, 1.

- 67. Steingrímur Jónsson, “Varastöð Rafmagnsveitu Reykjavíkur”, Tímarit VFÍ, vol. 33, n° 3, 1948, 29–51.

- 68. “Þetta var minn heimur”, Húsfreyjan, n° 2, 1951, 25–29, here 29.

- 69. On encouragement to drink and cook with geothermal water, see: “Hitaveituvatn síður en svo óhollt”, Vísir, 10/05/1976, 4; “Alvitur svarar bréfum”, Heimilistíminn, n° 19, 1978, 3.

- 70. Hrefna Kristmannsdóttir, Halldór Ármansson, “Vinnslueiginleikar Hitaveituvatns,” Lesbók Morgunblaðsins, 07/12/1996, 17.

- 71. See the account of a male (b. 1926) from Reykjavík in: Icelandic National Museum, Spurningaskrá 117: Híbýli, húsbúnaður og hversdagslíf.

- 72. See an overview of registered cases of colds in and outside Reykjavík during 1937–1948: “Hitaveitan og hvefið”, Heilbrigðismál, n° 4, 1962, 10–11, here 11.

- 73. “Húsmæðraþáttur: í þvottahúsinu”, Freyr, n° 4–5, 1954, 75–78.

- 74. Using geothermal water in electric dishwashers could damage machines and dishes: Anna Bjarnason, “Hitaveituvatnið eyðileggur bæði uppþvottavélina og leirinn”, DV, 01/11/1978, 4. There were experiments with special dishwashers for geothermal water, which did not spread widely. See the comments by two men (b. 1922 and 1932) on engineer Gísli Halldórsson’s geothermal dishwasher: Icelandic National Museum, Spurningaskrá 97: Rafvæðing II. Raftæki.

- 75. By the 1960s, many housewives who had no laundry rooms in their homes came with their own washing pots and machines instead of the old washing boards, or kept them in a storage facility on site: “Nú koma þær í bílum með þvottavélarnar sínar”, Morgunblaðið, 06/08/1960, 3.

- 76. The comment was published on the women’s page (kvennasíða) of the newspaper Þjóðviljinn: Sigríður Arnlaugsdóttir, “Hitaveita – hænsnabú”, Þjóðviljinn, 10/01/1945, 3.

- 77. Ibid.

- 78. My own family has a history of living outside the utility area, as my father (b. 1942) lived several years of his childhood in the 1950s in a “perpetually cold” house with a coal oven at Grímsstaðir in Western Reykjavík.

- 79. See e.g. an advertisement for kerosene ovens: “H.Í.S. Perfection steinolíuofnar”, Tímarit VFÍ, vol. 8, n° 3, 1923, 14.

- 80. See advertising campaigns for oil burners: “Hvers vegna nota allir sjálfvirka olíukyndingu?”, Fálkinn, vol. 19, n° 22, 1946, 16; “Olíukynding”, Morgunblaðið, 06/03/1945, 3.

- 81. Hagskýrslur um húsnæðismál, 1950, 33.

- 82. On the primary form of heating in Reykjavík dwelling units, see census data as visualized in Figure 4.

- 83. What people valued most about oil heating was the thermostat. See the account of a male (b. 1939) in the following questionnaire: Icelandic National Museum, Spurningaskrá 117: Híbili, húsbúnaður og hversdagslíf.

- 84. “Hvers vegna nota allir sjálfvirka olíukyndingu?”, 16. On the advantages of oil over coal heating, see also: Odinn Melsted, Pallua, Irene, “The Historical Transition from Coal to Hydrocarbons: Previous Explanations and the Need for an Integrative Perspective”, Canadian Journal of History, vol. 53, n° 3, 2018, 395–422, here 411–416.

- 85. “Hvers vegna nota allir sjálfvirka olíukyndingu?”, 16.

- 86. “Samskot fyrir borgarstjórnina”, Tíminn, 01/11/1957, 6; Guðmundur Vigfússon, “Tryggja veður öllum Reykvíkingum afnot hitaveitunnar”, Þjóðviljinn, 18/01/1958, 7–10.

- 87. Already in 1954, Gunnar Thoroddsen declared “district heating into every house” as his party’s main goal: “Hitaveita í hvert hús, er takmark Sjálfstæðismanna”, Morgunblaðið, 24/01/1954, 1–2. See also: “Hitaveita í allri Reykjavík eftir rúm 4 ár”, Morgunblaðið, 9/06/1961, 1–11; “Stærsta verkefnið næsta kjörtímabil að allir Reykvíkingar njóti hitaveitu”, Morgunblaðið, 24/05/1962, 35–36.

- 88. See the chapter “Hitaveita allra Reykvíkinga” in Björnsson, Saga Hitaveitu Reykjavíkur, 169–167.

- 89. Reykjavík Municipal Archives, Hitaveita Reykjavíkur I-138, Samanburður á kostnaði við hitun húsa með hitaveitu og gasolíukyndingu, 11/1970.

- 90. “Skýrsla iðnaðarráðherra um nýtingu innlendra orkugjafa í stað olíu“, Alþingistíðindi A, 1973–1974, 1766–1790, here 1767.

- 91. Björnsson, Saga Hitaveitu Reykjavíkur, 199–211.

- 92. Reykjavík Municipal Archives, Hitaveita Reykjavíkur I-134, Tölfræðilegar upplýsingar 1961–1980.

- 93. “Sjómannskonan sem situr í bæjarstjórn Hafnarfjarðar: viðtal við Elínu Jósefsdóttur”, Morgunblaðið, 24/05/1959, 9.

- 94. “Sparar fjölskyldu 3200: Húsmæður og hitaveitan”, Vísir, 25/05/1962, 16.

- 95. Later known as “equal pay day”, but generally seen more as a strike than a “day off”. See: Kristín Svava Tómasdóttir, “24. október 1975 – kvennafrí eða kvennaverkfall?”, Sagnir, vol. 29, n° 1, 2009, 19–25.

“Alvitur svarar bréfum”, Heimilistíminn, n° 19, 1978, 3.

Alþingistíðindi, 44. þing (aukaþing), C, 1931.

Arnlaugsdóttir Sigríður ,“Hitaveita – hænsnabú”, Þjóðviljinn, 10/01/1945, 3.

“Á föstu kaupi”, Morgunblaðið, 27/02/1966, 4.

Bak A.K., Johannes Hansen, “District Heating in Copenhagen”, District Heating, vol. 44, n° 4, 1959, 143–147.

Bjarnason Anna, “Hitaveituvatnið eyðileggur bæði uppþvottavélina og leirinn”, DV, 01/11/1978, 4.

Bjarnason Gunnar, “Höfum við gengið til góðs”, Búfræðingurinn, vol. 14, n° 1, 1948, 106–119.

Björnsson Lýður, “Í lánsfjárleit 1937–1939”, SAGA, n° 28, 1990, 63–85.

Björnsson Lýður, Saga Hitaveitu Reykjavíkur 1928–1998 (Reykjavík: Orkuveita Reykjavíkur, 2007).

Buckingham Susan, Rakibe Kulcur, “Gendered Geographies of Environmental Injustice”, Antipode, vol. 41, n° 4, 2009, 659–683.

Cherp Aleh, Vadim Vinichenkoa, Elina Brutschin, Benjamin Sovacool, “Integrating Techno-Economic, Socio-Technical and Political Perspectives on National Energy Transitions: A Meta-Theoretical Framework”, Energy Research & Social Science, n° 37, 2018, 175–190.

Cowan Ruth, More Work for Mother: The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Hearth to the Microwave (New York: Basic Books, 1983).

Euroheat and Power, “Statistical Overview: TOP District Heating and Cooling Indicators 2013”, euroheat.org, 03/2016. Url: http://www.euroheat.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/2015-Country-by-coun… (accessed 06/07/2021).

Frederiksen Svend, District Heating and Cooling (Lund: Studentlitteratur, 2013).

Friðriksson Guðjón, Saga Reykjavíkur: Bærinn vaknar, 1870–1940 I–II (Reykjavík: Iðunn, 1991–1994).

“Gasstöðin hefir kol í 25 daga: 4462 heimili í bænum nota gas til suðu”, Vísir, 28/09/1937, 3.

Gerber Sophie, Küche, Kühlschrank, Kilowatt: Zur Geschichte des privaten Energiekonsums in Deutschland, 1945–1990 (Bielefeld: Transcript, 2015).

Gooday Graeme, Domesticating Electricity: Technology, Uncertainty and Gender, 1880–1914 (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2008).

Gröndal Benedikt, “Hagnýting á hveraorku”, Tímarit VFÍ, vol. 13, n° 4, 1928, 33–35.

Guðmundsson Óskar, “Þvottalaugarnar í Laugardal”, Þjóðlíf, n° 9, 1990, 58–59.

Gunnarsdóttir Gyða, “Þarna var einu sinni líf í tuskunum”, Vera, n° 2, 1986, 20–21.

Gunnarsdóttir Margrét, “Þvottalaugarnar í Reykjavík: heilsulind Reykvíking”, Vera, n° 4, 1995, 14–15.

Halldórsdóttir Erla Hulda, Kristín Svava Tómasdóttir, Ragnheiður Kristjánsdóttir, Þorgerður Hrönn Þorvaldsdóttir, Helga Jóna Eiríksdóttir (ed.), Konur sem kjósa: aldarsaga (Reykjavík: Sögufélag, 2020).

Haraldsson Ingimar G., Þóra H. Þórisdóttir and Jónas Ketilsson, Efnahagslegur samanburður húshitunar með jarðhita og olíu árin 1970–2009 (Reykjavík: Orkustofnun, 2010).

Harrison Moore Abigail, Ruth W. Sandwell, In a New Light: Histories of Women and Energy (Montréal et al.: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2021).

Harrison Moore Abigail, Ruth W. Sandwell (eds.), “Women and Energy”, Special Issue of RCC Perspectives, n° 1, 2020.

Heffron Raphael J., Darren McCauley, “The Concept of Energy Justice across the Disciplines”, Energy Policy, n° 105, 2017, 658–667.

Herrero Sergio Tirado, Diana Ürge-Vorsatz, “Trapped in the Heat: A Post-Communist Type of Fuel Poverty”, Energy Policy, n° 49, 2012, 60–68.

“Hitaveitan”, Morgunblaðið, 02/07/1933, 3.

“Hitaveita í allri Reykjavík eftir rúm 4 ár”, Morgunblaðið, 9/06/1961, 1–11.

“Hitaveita í hvert hús, er takmark Sjálfstæðismanna”, Morgunblaðið, 24/01/1954, 1–2.

“Hitaveitan á að vera þjóðþrifamál”, Þjóðviljinn, 07/12/1937, 3.

“Hitaveitan og hvefið”, Heilbrigðismál, n° 4, 1962, 10–11.

“Hitaveituvatn síður en svo óhollt”, Vísir, 10/05/1976, 4.

“H.Í.S. Perfection steinolíuofnar”, Tímarit VFÍ, vol. 8, n° 3, 1923, 14.

“Hneyksli, sem aldrei var afhjúpað”, Alþýðublaðið, 17/07/1933, 2.

“Húsmæðraþáttur: í þvottahúsinu”, Freyr, n° 4–5, 1954, 75–78.

Hagskýrslur um húsnæðismál, 1950 & 1960.

“Hvenær kemur hitaveitan?”, Verkalýðsblaðið, vol. 7, n° 29, 1936, 4.

“Hvers vegna nota allir sjálfvirka olíukyndingu?”, Fálkinn, vol. 19, n° 22, 1946, 16.

Icelandic National Museum, Spurningaskrá 64: Hreingerningar og þvottur, 1986.

Icelandic National Museum, Spurningaskrá 96, Rafvæðingin I. Þegar rafmagnið kom, 1999.

Icelandic National Museum, Spurningaskrá 97: Rafvæðing II. Raftæki, 1999.

Icelandic National Museum, Spurningaskrá 117: Híbili, húsbúnaður og hversdagslíf, 2012.

Icelandic National Museum, Spurningaskrá 122: Aðstæður kynjanna, 2015.

Ísleifsson Sumarliði, Í straumsamband: Rafmagnsveita Reykjavíkur 75 ára (Reykjavík: Rafmagnsveita Reykjavíkur, 1996).

Jenkins Kirsten, Darren McCauley, Raphael Heffron, Hannes Stephan, Robert Rehner, “Energy Justice: A Conceptual Review”, Energy Research & Social Science, n° 11, 2016, 174–182.

Jones Christopher, Routes of Power: Energy and Modern America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014).

Jónasson Sigurður, “Hitun Reykjavíkur”, Nýja dagblaðið, 21/08/1938, 1 and 4, and (cont.) 26/08/1938, 1 and 4.

Jónsson Steingrímur, “Varastöð Rafmagnsveitu Reykjavíkur”, Tímarit VFÍ, vol. 33, n° 3, 1948, 29–51.

“Sogsvirkjunin”, Tímarit VFÍ vol. 23, n° 3, 1938, 21–50.

Kjartansson Helgi Skúli, Halldór Bjarnason, “Fríhöndlun og frelsi, 1830–1914”, in Sumarliði Ísleifsson (ed.), Líftaug landsins – saga íslenskrar utanlandsverslunar 900–2010 II (Reykjavík: Skrudda, 2017), 11–109.

“Kjósið hitaveituna í dag”, Morgunblaðið, 30/01/1938, 1.

Knudsen María J., “Almenningsþvottahús”, Nýtt kvennablað, n° 5–6, 1942, 1–3.

“Kolahækkunin er hrein okurtilraun af hálfu verzlanna”, Alþýðublaðið, 30/07/1937, 1.

“K-O-L”, Verkamaðurinn, n° 18, 1928, 4.

Kristmannsdóttir Hrefna, Halldór Ármansson, “Vinnslueiginleikar Hitaveituvatns,” Lesbók Morgunblaðsins, 07/12/1996, 17.

LaBelle Michael Carnegie, “In Pursuit of Energy Justice”, Energy Policy, n° 107, 2017, 615–620.

“Langþráð ósk, sem loks er að rætast”, Siglfirðingur, n° 26, 1936, 4.

Manzella Adele, Agnes Allansdottir, Anna Pellizzone (eds.), Geothermal Energy and Society (Cham: Springer, 2019).