Transnational capital markets and development policies: the OPEC countries, the Eurocurrency markets, and the LDCs from the 1960s to the 1970s

University of Naples L'Orientale

sselva[at]unior.it

In the wake of a recent literature in international banking and financial history focused on the role of western commercial banks in placing the OPEC nations' assets with international borrowers, this article examines the role of leading Wall Street American banks in reflowing the investments of the OPEC oil producing nations to finance the external disequilibria of the non-oil-producing LDCs as a tool of U.S. foreign economic policy during the 1970s. The article suggests that that such a policy aimed at the same time at propping up American development assistance programs to the LDCs and at fixing the decline of the dollar in the foreign exchange markets.

Against this backdrop, the article explores the shift of international financial assistance to the non-OPEC LDCs, from dollar-denominated assets mostly allocated by the IBRD before the end of the 1960s, to a set of new international financial arrangements based both on deposits from the OPEC countries with the Eurocurrency markets, and on the intermediary role of the leading American banks specializing in trading these non-resident markets to channel the revenues of the OPEC oil producers to the non-oil LDCs.

Plan de l'article

- Introduction

- Oil, dollar and the financing of U.S. development policies from the 1960s to the 1970s: an overview

- Teetering U.S. dollar, oil price hike and short-term Euromarket development: setting the stage for the early rise of U.S. private banks in international lending during the 1960s

- Reducing dollar-denominated assets before the end of cheap oil: the IBRD and the early ascendancy of international private capital markets on development finance

- U.S. private banks and the Eurocurrency markets: international loans to the LDCs amid the two oil price hikes of the 1970s

- Conclusion

Introduction

The leading literature on the first oil crisis of the 1970s, along with that on the history of development assistance implemented by the advanced industrial economies towards the least developed countries (LDCs), as well as the few works on the U.S. foreign financial and monetary policies toward the LDCs since the 1970s thereafter,1 all point to a set of widely-shared views on the energy crises of that decade and their link to the history of development assistance. First of all, they all point to the 1973 oil shock as the seminal event that lay at the origin of the decade's worldwide inflation. They make the argument that the first oil crisis triggered centrifugal effects on both the strength of the dollar in international markets and on the international trade and payments system that revolved around it.2 This research trajectory has pinpointed the financial implications of the first and second oil crises on the international capital markets during that decade. The oil revenues accruing to the oil-producing nations united in the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) as a result of the oil price hikes bolstered the role of OPEC countries as leading international lenders. Based on this premise, this literature has pinpointed varying hypotheses and negotiations conducted at the time between the industrial democracies, first and foremost the United States, and the OPEC countries on the recycling of their financial assets in the international economy. In particular, David Spiro focused attention on the U.S.-Saudi negotiations to trigger the investment of Saudis oil revenues in U.S. securities.3 Secondly, the literature on development assistance and U.S. foreign economic relations conveys a widely-shared view about the pivotal role of international economic institutions. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), as well as the regional development banks, shaped and nurtured the architecture of international financial assistance to the LDCs, not only in the first two post-war decades but also amid the gloomy 1970s, particularly at the turn of the decade.4 These two research trajectories tackled the history of how the oil-producing countries reinvested abroad their financial assets. They analyze either their investments in Western nations' public debt’s issues and securities, or their loans to the non-oil developing countries through the intermediary role of Bretton Woods international economic institutions and that of development banks. More recently, along the way of longstanding research interest on the role of western commercial banks in placing the OPEC nations assets with international borrowers,5 a strand of studies in banking and financial history has reversed this research pathway. This line of research has started exploring contributions by the European commercial banks to the international investments of the oil-producing nations, from the end of Bretton Woods international monetary regime to the outbreak of the second oil crisis at the turn of the 1970s.6 Continuing along this line of research, this article offers a first and partial reconstruction of the involvement of Wall Street commercial and investment banks in reflowing the OPEC financial assets to the non-oil LDCs from the first oil crisis up to the eve of the second oil shock. This exploration of the involvement of American private banking institutions in that recycling process is premised over two developments that featured the decade of the 1960s in international finance. On the one side the involvement of U.S. banks in the growth of short-term highly unregulated non-resident money markets on the European financial centres. The decade-long outflow of capital from American banks led U.S. bankers to soar their investment in non-resident currencies on European markets, the Eurodollar and other Eurocurrency markets, which offered easier borrowing conditions and more lucrative lending terms. On the other hand, the late 1960s pressure on the value of the dollar in exchange markets stemmed in part from a large-scale inflow of dollars in world money supply. This was the result of dollar-denominated assistance programs allocated by the IBRD and the IMF to the non-oil LDCs. To U.S. policymakers it was a pressing need to provide the LDCs with continued economic assistance without straining the dollar in the foreign exchange markets. A wide variety of late-1960s U.S. initiatives in international monetary relations that included the setting up of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), the currency of the IMF, and the involvement of largest American commercial banks in placing with international lenders the bonds and certificates issued by the World Bank to finance its development assistance programs, signalled this increased U.S. attention to the weakening of the American currency in foreign markets. They also point to Washington’s search for measures to reduce the dollar’s share in world money supply. This contribution pinpoints the shift of financial assistance to the non-OPEC LDCs, particularly the Latin American economies, from dollar-denominated assets allocated by the IBRD, the IMF and some federal agencies before the end of the 1960s, to a set of new international financial arrangements. These new arrangements were fuelled by deposits from the OPEC countries with the Eurocurrency markets and by the borrowing of the leading American commercial banks from these non-resident markets. These new financial dynamics are linked to both the increased U.S. attention to face up to the decline of the dollar in the foreign exchange markets and to continued American search to reduce the dollar’s share in world supply.

Therefore, the article focuses on the staggeringly crucial role of U.S. banks in promoting such a shift from LDCs borrowing from international economic institutions to international lending by private banks during the decade of the 1970s. In so doing, owing to the stunning increase in the OPEC countries' deposits with the Eurocurrency markets after both the first and the second oil crisis, this contribution makes the argument that the OPEC oil producers financed the sovereign debt, the current account deficit, and international trade of the non-OPEC LDCs. They did so through a decisive intermediary role by the leading U.S. commercial and investment banks that specialized in trading Eurocurrency assets. Therefore, this article establishes a linkage between the investment of OPEC's oil revenues in high interest-sensitive and largely non-regulated international markets on the one hand and the increased exposure of U.S. commercial and investment banks to financing the foreign debt, balance of payments deficit, international trade and foreign currency reserves of the LDCs over the decade on the other hand. According to this reconstruction, during the 1970s the Eurocurrency markets, first and foremost their Eurodollar component, which accounted for the largest share in total Euro-loans, became the point of intersection between the OPEC countries' international investments and the international intermediary activities of the largest U.S. banks committed to financing the LDCs. Such a new role of non-resident Euromarkets and U.S. banks brought the American financial community to a center stage in shaping the foreign financial relations of the United States way before the meteoric rise of non-OPEC LDCs' liabilities to the 8 largest U.S. commercial banks at the beginning of the 1980s. Therefore this contribution suggests that America’s largest commercial and investment banks were deeply involved in injecting money into the LDCs and overexposed to them way before the international debt crisis erupted. In other words, from the late 1960s through to the inauguration of monetary stringency by the newly appointed President of the U.S. Federal Reserve System Paul Volcker at the beginning of the 1980s, U.S. commercial and investment banks offered a critical contribution to the setting up and implementation of international financial arrangements alternative to U.S. currency-centered development assistance programs to the LDCs. This article explores the role of American commercial banks from the late 1960s through to the following decade to pinpoint the early overexposure of U.S. banks to the LDCs. However, it does not tackle the period following the 1979 historical decision of the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank to uptick interest rates. At the time the U.S. banks overexposure to the LDCs borrowers soared as a result of peaking interest rates.

Back to topOil, dollar and the financing of U.S. development policies from the 1960s to the 1970s: an overview

Before reconstructing the details of the story it is worth providing an overview of the macroeconomic developments of the time. From the second half of the 1960s through to the two oil crises of the 1970s it was registered a combined crumbling of stable oil and raw material prices in the world trade market, and an unfettered drop of the dollar in exchange markets with ever-growing U.S. balance of payments deficit and soaring U.S. foreign trade deficit. Moreover, this period featured continued outflow of dollar-denominated capital from the U.S. money markets to the very lucrative Eurocurrency markets.7 Though in 1969 the U.S. government instituted a 10 percent reserve requirement on lending by the overseas branches of U.S. banks to U.S. resident banks and companies,8 on the eve of the new decade capital outflows from the United States had hit hard the U.S. capital account. On the other hand, the weakening of the dollar in the foreign exchange markets and the appreciation of other leading currencies against the green currency increased the cost of U.S. imports and plunged the U.S. trade balance into deficit.9 Against this framework the system of world trade and payments revolving around the U.S. dollar as a means of payment began floating: a weakened dollar reduced dollar-earnings for the oil and raw material exporting developing nations. These countries were pushed on the periphery of world trade and forced to accumulate rising debts to reward their foreign suppliers of goods and services.

These different developments and America’s pressing need to search for diversifying international financial assistance to the LDCs out of dollar-denominated assets represent the broad framework in which took place the involvement of American banks, used to trading in the Eurocurrency markets and in channeling OPEC resources to the developing world. Prior to focusing on such role of U.S. banks, this article pinpoints the interconnection between the depreciation of the dollar in the foreign exchange markets and the long-lasting worsening of the U.S. balance of payments deficit, the growth of oil and other commodities prices, on the one side and American reaction to these developments. Accordingly, this contribution focuses on the U.S. search for international financial arrangements alternative to dollar-denominated assistance programs designed to help the non-oil LDCs resurrect their current account deficit. From the very late 1960s throughout the following decade, the U.S. government and the largest U.S. banks worked on establishing a set of development assistance policies toward the non-oil-producing LDCs and the highest capital absorbing Middle Eastern OPEC member states. These arrangements were designed to prevent the LDCs and Middle Eastern oil producers from falling apart from the international trade and payments system. Such search for establishing brand-new financial mechanisms was thought to be an alternative to official dollar-denominated development assistance programs carried out over the postwar decades by Bretton Woods development institutions such as the IBRD.10 Along this line of reasoning, section 3 briefly charts the combined development of declining U.S. dollar induced by short-term capital outflows from the United States. Besides, it pinpoints the growth of non-resident Eurocurrency markets and oil price rise in world trade markets in the second half of the 1960s. All these developments contributed to undermining dollar-denominated official assistance programs to developing countries. Through the case study of the IBRD, section 4 sums up the main features of development assistance during the late 1960s: at the time the weakening of the dollar caused by the two-fold crumbling of U.S. currency in exchange markets and rising instability in international oil prices prompted the United States to devise new development assistance programs to the non-oil LDCs. As these new arrangements were thought to be based on a currency diversification out of the dollar from the 1960s to the 1970s, the U.S. private banks were charged with pursuing this objective. Accordingly, at the end of the 1960s, they began placing bonds issued by the IBRD with several different national credit markets. During the 1970s, they bet on the Eurocurrency markets as a new form of currency diversification out of the dollar and as a way to sustain the value of the U.S. currency in the foreign exchange markets.11 Section 5 pinpoints this commitment of the largest American commercial and investment banks: it makes the argument that since the first oil crisis, the bulk of the economic assistance to the non-oil LDCs was made of deposits by the OPEC oil producers with the Eurocurrency markets. The U.S. banks, used to trading in the Eurocurrency markets, played a crucial role in channeling such deposits to the non-oil LDCs. The epicentre of these lending activities were the Latin American developing countries, first and foremost Brazil and Mexico. This section provides fresh-new archival data about such interlocking between the oil producers' international financial investments, U.S. banking, and the Latin American borrowing nations. In the Conclusion, we round off by stressing continuities and discontinuities from the 1960s to the 1970s. In either decade, the pivot that underpinned the involvement of U.S. commercial banks in financing multiple and different development assistance programs such as the IBRD projects and international lending by transnational financial markets, was devising financial arrangements based on currency units or baskets of currencies alternative to the U.S. currency. This objective was pursued to align the financing of development policies with the support for the U.S. currency in international markets. On the other hand, this article stresses that the Eurodollar and other Eurocurrency markets had a strikingly different impact on the U.S. currency in the context of development assistance. During the late 1960s they contributed to weaken the U.S. currency. In contrast to it, by the mid-1970s, within the framework of the recycling of the OPEC international investments, the Euromarkets fit into the plot of financing the external position of the non-OPEC LDCs, without pressurizing the U.S. dollar and its value in exchange markets.

Back to topTeetering U.S. dollar, oil price hike and short-term Euromarket development: setting the stage for the early rise of U.S. private banks in international lending during the 1960s

All along the 1960s the United States showed intractable incapability to resurrect the U.S. current account component of the U.S. balance of payments deficit. Under way since the very late 1950s, during the following decade the U.S. balance of payments deficit plunged the dollar into a seemingly intractable decline in exchange markets. The staggering expansion in short-term highly-liquid Eurodollar and Eurocurrency markets highly contributed to the downward spiralling value of the U.S. currency. Under the Kennedy administration and throughout the 1960s, the United States set up a variety of measures to resurrect the U.S. balance of payments deficit. These measures mainly revolved around targeting the current account deficit and included discouraging U.S. overseas military expenditures to reduce the liabilities on the U.S. current account deficit. Likewise, the U.S. governments made arrangements to increase the assets of the current account position through export-promoting policies. On the other hand, federal authorities tackled the U.S. capital account position. They struggled to fix it up through preventing capital outflows for which they used measures such as the Voluntary Foreign Credit Restraint Program (VFCR), an initiative seeking to limit the increase of foreign loans and investments of U.S. private financial institutions. Established in 1965 as a balance of payments deficit-correcting measure, the VFCR was strengthened in 1968, and still under operation in the early 1970s.12 This string of measures on both the current and the capital account failed to reduce the outflow of U.S. dollar-denominated assets and to stabilize the U.S. balance of payments. This failure can be blamed on the parallel growth of the Eurocurrency markets. The Euromarkets were assets denominated in currencies other than that of the country where they were traded. As non-resident currencies, they were neither bound to reserve requirements or interest ceilings, nor did they have to pay local or federal taxes in the United States. They took advantage from such condition of non-resident assets to increase their competitive edge on financial assets and transactions subject to national regulations and costs. During the late 1960s and for most the 1970s they could profit from an exceptionally performing competitive advantage over the interbank markets and other resident-currency national markets. Besides, in the case of U.S. investors and the overseas branches of U.S. banks trading in the Euromarkets, they were not subject to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) regulations.13 As such, the Eurocurrency markets could at the same time offer lucrative interest rates on depositors and concede very competitive loan rates to borrowers. Owing to growing international investments of U.S. corporations, increased U.S. military spending overseas, and large holdings of dollar assets by non U.S. residents in Europe and elsewhere, the dollar component of the Euromarkets, the so called Eurodollars, accounted for the largest share in total Eurocurrency assets. Since the early development and expansion of the Eurocurrency markets in the first half of the 1960s, Eurodollar deposits, excluding interbank Eurodollar placements, reached a total of some $ 5 billion out of an aggregate Eurocurrency market of roughly $ 7 billion.14 In the second half of the decade, U.S. measures to discourage foreign investments of U.S. resident banks and companies, and loans of U.S. banks to foreign borrowers, stimulated short-term capital flows from the United States to the Eurodollar markets. Monetary tightening in the United States in 1967, wide-spread rise in U.S. domestic interest rates, and the parallel credit crunch the following year prompted U.S. banks to increase their borrowings from the Eurodollar markets to finance the U.S. economy, thus leading to temporarily reverting such outflow of dollar assets from the United States.15

The U.S. Federal Reserve was aware of these dynamics: the American central banks’ policymakers noticed that monetary tightening could cause a credit crunch and prompt U.S. domestic banks to borrow even larger amount of money from the Eurodollar markets. According to the Fed this increased borrowing by U.S. banks from the Eurocurrency markets could push up the Eurodollar rates. In turn this upswing in demand for unregulated European money markets could make the Euromarkets an investment outlet attractive to American and other international investors.16 During the decade of the 1960s and into the first half of the following decade, this combined capital outflow from the United States of short-term dollar-denominated assets and rising borrowing from the Eurodollar market by U.S. resident banks coincided with a period of shrinking U.S. balance of payments deficit. Besides, during that decade, capital flight from the United States hit further the value of the U.S. dollar in exchange markets.17

Such sequential capital outflow, increased borrowing by U.S. banks in foreign capital markets, plunging dollar in exchange markets, and sinking U.S. balance of payments deficit paired with a steady rise in oil prices way before the quadrupling of oil prices since 1973. A first substantial increase in the posted price of oil occurred as early as 1967;18 then, free-market crude petroleum prices hiked up in 1971.19 Certainly, there was a linkage between these trends: the unfettered weakening of confidence in and depreciation of the U.S. dollar, the currency in which most oil transactions and payments were traded, critically contributed to the early increase in petroleum prices. On the other hand, a variety of events crucial to the history of international monetary and financial relations in the late 1960s as the Suez Crisis, the 1968 gold crisis and the 1967 devaluation of the British Pound added to the inflationary impact of such combined oil price hikes and capital flight from the U.S. money market already underway.20 These events added to the increase in the dollar component in world money supply and overlapped with ongoing shifts in money markets from fixed or adjustable assets to short-term, largely unregulated and inflation-sensitive Eurocurrency instruments. These transformations went all in the same direction of hurting the dollar's rate in exchange markets, ravaging the U.S. balance of payments and setting conditions for inflationary strains across the international economy. Neither policies implemented throughout the 1960s by the Kennedy and Johnson administrations to resurrect the capital and current account positions of the U.S. balance of payments proved to be effective. Neither measures to curb capital outflow nor initiatives to cut overseas military expenditures while increasing foreign military sales halted the sinking of the U.S. balance of payments. The resulting weakening of the dollar in exchange markets and soaring U.S. balance of payments deficit brought the issue of reducing the dollar component in world money supply to center stage both in the late decade debate on the reform of the international monetary system21 and in the discussions on the creation and use of the IMF's currency, the Special Drawing Rights (SDRs). The SDRs, established in 1968, were to cope with the monetary and financial consequences on the dollar and international payments of wobbling fixed exchange rates and soaring posted prices of commodities in international markets. Their creation stemmed from widespread U.S. concerns in international monetary affairs to devise a new international reserve unit to supplement dollar-denominated international liquidity. The creation of a new reserve unit was supposed to reduce the share of the U.S. dollar in world money supply and push up the value of the U.S. currency in exchange markets.22 Increased American concern for the decline of confidence in and value of the dollar in international exchange markets not only underpinned the debate on the reorganization of the international monetary system. Indeed, it also prompted American elites to seek means of payment alternative to the U.S. currency to forestall such rise of the dollar share in world money supply and to prevent its role of reserve currency from fading away. It is worth placing against this new backdrop of international monetary relations both the rapid ascendancy of U.S. commercial and investment banks in shaping the late 1960s official development assistance programs implemented under the aegis of the World Bank and, more importantly, the critical contribution of the largest U.S. private banks since 1974 to the recycling of the OPEC countries dollar-denominated oil revenues. In the first case, the American banking system and some European private commercial banks financed the IBRD development assistance programs. They pursued this objective by placing bonds and securities issued by the IBRD with international investors used to trading financial assets denominated in currencies other than the U.S dollar. On the other hand, during the 1970s the U.S. and European private banks financed the international trade, foreign debt and current account deficit of the Latin American debtor nations by drawing on the OPEC countries' oil revenues invested in non-resident Eurocurrency markets. In either case, the functioning of these financing mechanisms permitted to finance development assistance without pulling liquidity from dollar-denominated assets, thus helping to reduce the share of dollars in world money supply. Unmistakably the U.S. commercial and investment banks played a critical and pivotal role in the pursuit of this objective. The growing share of commercial bank lending and the decline in export credit and Official Development Assistance (ODA) from 1960 to 1983 tracks this development in the medium term.23 The next two sections explore the critical role of U.S. commercial and investment banks in trying to resurrect the value of the U.S. currency in the foreign exchange markets first through the aforementioned new fund-raising policy carried forward by the IBRD, and later on through their full involvement in channeling the OPEC financial assets to the largest debtor nations via the Eurocurrency markets.

Back to topReducing dollar-denominated assets before the end of cheap oil: the IBRD and the early ascendancy of international private capital markets on development finance

From the postwar decade to the 1960s both U.S. government's official assistance, and the widespread financial involvement of the IBRD in nurturing development assistance programs to the non-oil-producing LDCs had rested on two linchpins: the stability of posted prices of oil in world trade markets and that of the dollar in exchange markets. Based on these two conditions, during those decades neither the non-oil LDCs current account deficit grew staggeringly owed to sudden changes in oil prices, nor were the institutional financial assistance programs established at international level in support for the LDCs reshaped to reflect any changing value of the U.S. currency in exchange markets. As a proxy for this it is worth mentioning that until the 1960s the dollar was by and large the currency of denomination for most financial assistance programs to the LDCs. The IBRD programs were the most remarkable example of this development: until the second half of the 1960s the IBRD raised dollar-denominated funds in its advanced industrial nations member states. At the time the Washington-based Bretton Woods institution pursued this fund-raising policy by drawing on its members' Central Banks and quotas without resorting to currency diversifications to finance its assistance programs. All this changed in the second half of the 1960s. The combined decline of the dollar in exchange markets and the crumbling oil prices in world trade markets forced the IBRD to reshuffle its development assistance programs to the non-oil LDCs. At the same time these developments led U.S. authorities to bring the American financial community to center stage in the American effort to help abating the non-oil LDCs current account deficits and sovereign debt. After charting the plunging of the U.S. dollar in exchange markets and the teetering of oil prices prior to 1973, it is worth briefly investigating -through the case study of the IBRD's changing borrowing patterns- this historical turn from dollar-denominated assets to the new mechanisms that U.S. authorities devised to provide the non-oil LDCs with continued financial assistance packages against the framework of teetering dollar in exchange markets and wobbling oil prices. The increasing tendency of the OPEC countries to deposit their oil revenues with the Eurocurrency markets during the decade of the 1970s brought about two landmark transformations in the shaping of assistance to the non-oil LDCs. In the first instance the U.S. commercial banks and other private intermediaries got involved in the process at impaired level. Secondly, it was registered a fundamental shift from dollar-denominated assets to Eurocurrency assets, mostly denominated in non-resident Eurodollars, and other non dollar assets. The reshaping of the IBRD official development assistance in the late 1960s came about exactly along these two lines of development: since the appointment of McNamara to the presidency of the IBRD, the bank reorganised its official development assistance to the LDCs by charging the largest U.S. commercial banks with borrowing on its behalf on international markets according to a strict currency diversification principle.

All along the two decades from its establishment to the years before the launching of McNamara's ambitious war on poverty, the Washington based institution had resorted to borrowing from private financial institutions and from currency areas other than the U.S. dollar only to a rather limited extent.

From the early 1950s to the early 1960s, under the Presidency of Eugene Black, former senior Vice President of Chase National Bank, the IBRD established and expanded the market for its securities in the world's investment centers. President Black committed himself to place bonds issued by the IBRD with the European investment centers. For instance, at the start of the 1950s, the IBRD and the Swiss government entered an agreement under which the Washington-based institution was granted tax reductions in connection with the issue of IBRD bonds in the Swiss private capital market.24 By coupling such expansion of the World Bank's borrowing from the international financial centers with the sales of returns on its loans, under the presidency of Black the IBRD could raise funds in the private markets for a total of up to roughly the equivalent of $ 2 billion, with more than half of its borrowing outside of the United States.25

Within the framework of this struggle to issue a growing number of bonds and securities in the private markets, at the time the IBRD tried to diversify the currency composition of its borrowing.

Notwithstanding these attempts, by the early 1960s the IBRD still substantially relied on the U.S. capital markets and largely borrowed from U.S. investors and dollar-denominated credit lines. For instance, at the beginning of that decade, the IBRD failed in placing some bonds with west European national capital markets.26 Furthermore, tellingly, in 1964 U.S. private investors snapped up the largest portion of $ 200 million offerings of bonds issued by the IBRD that year.27 Therefore, from the time the U.S. balance of payments plunged in the late 1950s to the attempts conducted under the Kennedy administration to restore equilibrium through the implementation of balance of payments deficit financing policies on the current account position, the IBRD financial relations with the international capital markets did not clearly contribute to a diversification of its investment out of the dollar area. Rather, the Bank attracted American investors and other investors used to trading dollar-denominated assets.

By contrast, from around 1967 to the eve of the new decade, the borrowing policies of the IBRD changed staggeringly: it was registered a markedly turn in its borrowing from the U.S. dollar to other currency areas. The Bank increasingly placed its bonds and securities with private commercial and investment banks that offered investment portfolios based on a basket of different currencies. This diversification of the IBRD investment portfolio eased off pressure on the U.S. currency for bearing the cost of financing development finance. From the appointment of former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara to the presidency of the IBRD to the end of the decade the Washington-based institution repeatedly resorted to West European capital markets to finance its development assistance programs.28 This new borrowing pattern led the Bank to center stage in shaping development assistance policies.29

A few months after the appointment of McNamara to the head of the IBRD, some of the World Bank's high-ranking officials met representatives from the largest U.S. banks to discuss their participation in financing the new president's ambitious plans to expand the World Bank’s lending operation to finance development policies across the globe. Along with fierce criticism on the part of American bankers as for the very low lending rate offered by the IBRD to the American banking system, the very topic at the center of these conversations was the currency denomination of the Bank's bonds and securities offered. Bank of America's representatives and officials of Brown Brothers Harriman, for instance, called attention to the implications of the U.S. balance of payments deficit on the bankability of U.S. dollar-denominated bonds issued by the IBRD.30 One year later, while leading U.S. financial institutions as Morgan Stanley stressed “the need for the Bank to renew and broaden its contacts in the investment community in the United States; and for McNamara to become better known to that community”,31 the IBRD had issued a substantial portfolio of bonds in currency markets other than the dollar. In particular, from late summer 1968 to late summer 1969 the Bank conducted a currency diversification policy by offering both public and private issues in the German markets and in the Swiss capital market.32

Later on, favored by the United Kingdom and other Western European partners, McNamara turned to draw on the oil-producing countries of OPEC to finance the bonds issued by the IBRD.33 As of 1968, the IBRD had borrowed in the London market on three occasions,34 while by fiscal year-end 1969 over half of the Bank's gross borrowing had been raised in the German and U.S. private capital markets.35 The case of German private capital markets is particularly noteworthy. Over the decade some world-class German banks purchased an increasing volume of bonds issued by the IBRD. For instance, Giro Zentrale (GZ) and Deutsch Bank bought significant portions of World Bank-issued bonds and securities and pledged to make public and private placements in the German markets.36 The involvement of German banks in financing the IBRD programs was a means of easing the burden of the IBRD development assistance programs on the U.S. balance of payments, as well as of supporting the value of the dollar in the foreign exchange markets.

This growing involvement of private western commercial banks in financing McNamara's war on poverty provided a critical contribution to the promotion of development assistance on a world scale. A rough estimation of the increase in private funding for the developing countries before the 1970s reports a surge in private capital flows from 40 percent of the total in the period 1964-1966 to 44 percent in 1970. 37

This significant change that featured the borrowing patterns of the IBRD helps tracking the two landmark transformations that shaped development assistance programs to the non-OPEC LDCs since the U.S. currency began teetering and the international trade and payments system was ravaged by unstable exchange markets, creeping oil prices and sinking U.S. balance of payments deficit. In the first instance, the search for means of payments and a currency unit to price raw materials and goods exchanged in international trade alternative to the dollar. Secondly, the stunningly central contribution that the western private commercial banks gave to this transformative process. In the case of the World Bank, the involvement of private commercial banks let the IBRD issue bonds and securities that could be financed by raising money in money markets other than the U.S. dollar area and could be pegged to a basket of currencies. This process could not only reduce the amount of dollar-denominated assets traded in international money markets. It was also useful in minimizing the exchange risk for investors and to defend the U.S. currency in the foreign exchange markets, thus propping up the U.S. balance of payments.

The next section suggests that amid the two oil crises of the 1970s these same objectives be pursued. At that point, the unregulated Euro-dollar and other Eurocurrency markets became a new instrument to finance development assistance to the non-OPEC LDCs. Resorting to the Eurocurrency markets and to the OPEC countries’ deposits in them made it possible to finance the battle of the LDCs against the decade’s international inflation. They also partially offset the impact of the mid-1970s economic recession that plagued the advanced industrial economies on their terms of trade without straining further the U.S. currency and balance of payments through dollar-financing official development assistance.

Back to topU.S. private banks and the Eurocurrency markets: international loans to the LDCs amid the two oil price hikes of the 1970s

As pointed out in section 4, at the turn from the 1960s to the 1970s the IBRD development assistance programs took place in connection with this increased involvement of international private intermediaries in fuelling development assistance to the LDCs. This also helped to reduce U.S. federal transfers to the World Bank and the strains they caused on the U.S. government deficit. Most importantly, the involvement of U.S. and other Western commercial banks was aimed to reduce the dollar share in world money supply. This diminished dollar share helped sustaining the purchasing power of the dollar in international trade and financial transactions. Likewise, in Washington the debate on the implementation of Special Drawing Rights was intended to prop up the U.S. currency in exchange markets by substituting the dollar as the unit of international accounts. The objective was to lessen the effects of a weakening U.S currency on international trade.38 Therefore, way before the first oil crisis erupted, two key components in the shaping of international financial assistance to the developing countries during the 1970s -U.S. commercial banks and transnational financial markets intended as means of payments and units of accounts alternative to the U.S. dollar- were already under operation. The first oil shock made way for a new player to emerge: the OPEC countries, itself a giant group of international investors. This section outlines how the OPEC countries and their international financial might did play out in this process and tries to assess whether or not they contributed to decreasing the dollar component in world money supply.

At the end of 1974, many months after the outbreak of the first oil price hike, the OPEC countries oil surplus had strikingly surged close to $ 70 billion.39 By that time the LDCs run a combined trade deficit of about $ 25 billion.40 The way the OPEC oil producers distributed their international investments sheds light on the importance of oil producers, transnational financial markets, and western commercial banks, in reshaping the structure of development assistance to the non-oil LDCs since as early as the first oil shock. By December 1974 the OPEC countries placed as many as 40 percent out of their total foreign investments with non-resident Eurocurrency assets. From 1974 to 1975 the OPEC member countries' placements with the Euromarkets jumped from just over 30 percent to about 45 percent of their total overseas investments.41 At the same time, during the two years up to mid-1975, their direct loans to the non-oil LDCs rose substantially, whereas their investments in long-term U.S. and U.K. government securities declined.42 These data highlight a substantial shift in the direction of the OPEC countries’ international investments from long-term securities to short-term highly liquid assets as the Eurodollar markets. In the meantime, not coincidentally, according to IMF estimates, gross commercial bank lending to the non-oil LDCs increased from $ 9 billion in 1973 to $ 22 billion at year-end 1975, rising from 38 percent of total borrowings to 50 percent.43 Furthermore, at year-end 1975 the western banking system accounted for the largest amount of claims on the developing countries' private sector debt, which amounted to $ 66 billion. On the other hand, the public sector debt of the non-oil LDCs were liabilities to western governments or to private foreign banks warranted by their national governments. In order to understand to what extent western banks lending came to center stage in the process of financing the non-OPEC Latin American LDCs it is worth mentioning that by 1975 U.S. private banks were reported to hold two-third of total $ 66 billion private sector debt. At the same time, Mexico and Brazil owed to western banks nearly one-half or almost $ 30 billion out of total $ 66 billion private sector debt. The remaining largest Latin American debtors (Argentina, Chile, Perù and Colombia) accounted for one eight or about $ 8 billion of total liabilities owed to western banks.44 Therefore, from as early as the years 1973 to 1975, U.S. banks held the largest share of the Latin American countries' private sector debt. On the other hand, from 1971 to 1975 the LDCs had increasingly borrowed short-term assets from Western banks.45 As at the time most of the western banks’ short-term investments were in the Euromarkets, this borrowing pattern helps establishing a linkage between the increased dependence of the LDCs on western commercial banks and the latter ones capability to trade in the Eurodollar and other short-term Eurocurrency markets. The American and other western commercial banks borrowed in the Eurocurrency markets to lend to the LDCs. Furthermore, this occurred even as the OPEC oil producers shifted their investments from long-term assets to short-term Euromarkets. Thus, it is worth establishing a connection between placements by the OPEC with short-term Euromarkets, increased trading by the Western commercial banks in the Euromarkets, and the strikingly rise of LDCs’ borrowings from the American and other western banks specialised in trading short-term Eurocurrency assets.

One more point is noteworthy to complete this overview of the increasing involvement of American commercial and investment banks in international financial markets and in financing international development policies. Way before 1973 the largest U.S. banks had established overseas branches across the Mediterranean and Middle Eastern oil producers featuring the largest consumer markets: countries as Iran and Libya had become market outlets for U.S. manufacturing and service industry. Within this framework, the U.S. commercial banks had served as export-promoting or import-financing intermediaries long before the outbreak of the first oil crisis.46 Therefore, by the time the 1975 worldwide recession broke out, the largest U.S. commercial and investment banks had long served as a point of connection between the OPEC oil-producing countries and the industrial world.

However, it was only shortly after the first oil price hike that American banks became a critical point of intersection between the OPEC oil revenues, the new highly unregulated transnational Euromarkets, and the financing of the non-OPEC LDCs' external disequilibria. The U.S. monetary authorities played a decisive role in bringing U.S. commercial banks to center stage in channeling the OPEC oil revenues to finance the LDCs current account deficit. As of 1974, notwithstanding repeated reluctance by U.S. bankers to reinvest the OPEC financial assets in the LDCs due to the poor creditworthiness germane to the developing countries,47 the overseas branches of U.S. banks used to trading non-resident Eurocurrency assets, financed a growing share of the LDCs current account deficit. On the whole, the international banking system financed approximately half of the current account deficits of the oil imported from OPEC by the developing countries.48 This contribution of U.S. commercial banks to finance the balance of payment on the current account of the non-OPEC LDCs begun way before the first oil shock, developed further at mid-decade, and grew even larger in the second half of the decade. This widespread American involvement in financing the LDCs external deficit continued up to the outbreak of the turn-of-the-decade debt crisis since 1980.49 Before briefly assessing the increasing involvement of American banks in the second half of the 1970s it is worth pinpointing the string of causes that pushed them forward. To account for this decade-long involvement of the largest U.S. banks in financing the current account position and foreign debt of the Latin American non-OPEC LDCs it is worth pointing out three factors. In the first instance, the developing countries accounted for 40 percent of total U.S. export. This factor continuously prompted the United States to promote financial assistance to the LDCs, and particularly to the Latin American economies, all along the decade of the 1960s and 1970s. This U.S. export-promoting policy continued until the second oil crisis brutally squeezed commercial relations between the United States and Latin America. It is worth recalling that by 1982 -amid the Latin American debt crisis- U.S. total export fell by 5 percent, whereas American export to Latin America was down by 8 percent, to Mexico by 20 percent and to Brazil by 13 percent.50 Consider the impact of the first oil price hike and the international inflationary spiral triggered by the expansionary policies of the Nixon administration and the UK government on the current account position of the non-OPEC LDCs.51 From 1974 to 1975 the non-OPEC Latin American developing nations suffered from both a worsening current account deficit and a decline in their current account assets. The shrinking of the current account deficit was caused by the increased cost of consumer goods that Latin American countries imported from oil price hike-hit advanced industrial nations. Furthermore, a decline in export of raw material to Western Europe as a result of the 1975 recession lays at the origins of the non-oil LDCs diminished assets, on the current account position that those economies suffered from at the time.52 Therefore, within the framework of the recession that followed the first oil price shock, not only did the LDCs reduce imports from the United States and other advanced industrial nations. They also suffered from shrinking export in raw material and other strategic products to the industrial economies. At the time U.S. monetary authorities, and particularly the Fed, exerted pressure on the American bankers to commit fully on financing the LDCs, and particularly the non-oil LDCs, in order to prevent them from falling into a plaguing recession and to avoid a decline in U.S. export.53 The second development that explains the increased centrality of U.S. commercial and investment banks in shaping and financing development assistance to the LDCs traces back to 1972. At the time the expansionary monetary and fiscal policies inaugurated by the Nixon administration stimulated a rise in international demand for consumer and investment goods as well as for raw and strategic material. As a result of such dynamics, the price of raw materials produced in the LDCs surged substantially. This development made the non-OPEC LDCs more appealing to western commercial banks: American and other western banks improved their rating of the LDCs creditworthiness and opened new credit lines to the LDCs. This process triggered an increase in the liabilities of the LDCs to western banks and laid at the origins of an inflationary spiral caused by both an upsurge of raw material prices and expanding world money supply.54 In the third instance, by the mid-1970s the Latin American LDCs resorted to western private banks for three institutional reasons. The first reason was the easiness of pleading for funds from private banks compared to the lengthy and uncertain process of filing requests for borrowing from international economic institutions like the IMF, the multilateral development banks or the IBRD. Not coincidentally, in the second half of the decade, some of the largest U.S. private banks ventured on offering extensive lending to Latin American borrowers.55 The second institutional reason that since the mid-1970s drove the non-OPEC LDCs to borrow large amounts of funds from the western banking system, and particularly from the 8 largest U.S. commercial banks, was the ill-functioning and unequal distribution of the OPEC oil revenues after the first oil price hike. At year-end 1975 the largest amount of the OPEC oil revenues that the oil producers had placed with the international money markets were put to finance the balance of payments deficit of the advanced industrial nations. This was the case for both the project to establish an OECD financial arrangement to finance its member countries, and the IMF oil facility, a financial arrangement designed to help countries whose balance of payments had been hit the most by the first oil price hike. According to statistical data, the oil facility devoted the bulk of its assistance to advanced industrial nations suffering from shrinking current account deficits.56 The third institutional reason that prompted the LDCs to borrow from western banks extensively, was unmistakably the fact that by the time the 1975 recession hit the advanced industrial nations, most of them had stretched to the limits of holding the debt of the LDCs. Much the same was the case of the IMF: the Bretton Woods institution increased its member quotas precisely in order to finance the external debt of developing countries. Unlike the importance given in the economics and historical literature to the role of the IMF and the World Bank in nurturing the external equilibrium of the LDCs in the second half of the decade, the IMF lagged behind its official lending commitment all along the decade. At the beginning of the 1980s, within the framework of a turn-of-the-decade Washington debate about the feasibility of making the Fund directly borrow from the private capital markets and commercial banks,57 the Fund made arrangements with the U.S. government to borrow from it a financial assistance package that the Washington government had borrowed from private capital markets. In exchange for such credit lines, the U.S. government could draw on the IMF SDRs, and the IMF was supposed to repay the loan at the current Eurodollar loan rates.58

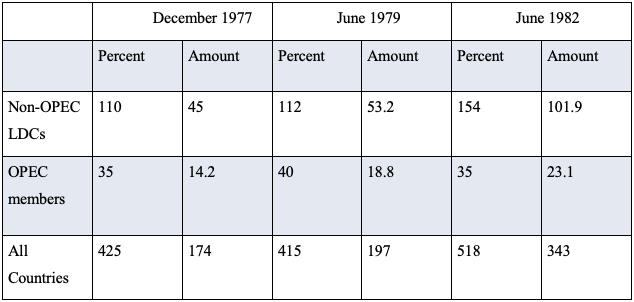

These multiple factors led U.S. commercial and investment banks to get increasingly involved in financing the current account deficit and the sovereign debt of the non-OPEC LDCs, first and foremost the Latin American nations. This involvement began before 1973 when private commercial banks began trading bonds and securities issued by the IBRD. Then, this new role of American banks mounted out of the striking international economic imbalances in world trade and payments after the first oil crisis and continued unfettered in the second half of the decade. A close look at unpublished archival data helps making a quantitative assessment of this development in the second half of the 1970s. From 1977 to 1979 the ratio of international lending to capital assets of the 8 largest U.S. banks increased constantly. However, the turning point on the way down to the overexposure of U.S. banks to poor-creditworthy developing nations occurred in June 1979. At that time, spurred in part by the second oil price hike, the rate of growth in lending outstripped the growth in capital assets. Noticeably, such increase in lending relative to capital funds was particularly intense in respect to the non-OPEC LDCs, where the bulk of U.S. banks exposure was concentrated (see table 1).

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, "Concentrations of Country Risks", 17.02.1983, in FRBNYA, b. 553726

Within the framework of this increased exposure in international lending, the geographic distribution and destination-specific of these lending activities of U.S. banks changed substantially. Until 1974, Eurocurrency lending was concentrated in the 9 Bank for International Settlements (BIS) reporting countries and mostly distributed with banking institutions: in 1974 the Eurocurrency market shared the largest percentage out of total credit supply to European borrowers. However, since 1975 onwards, Eurocurrency lending came through a historical shift: at the time it was reported a landmark increase in Eurocurrency claims against domestic and foreign non-banks,59 and the bulk of claims were against non-BIS member countries, including the developing countries. This trend sheds light on the changing trajectories of Eurocurrency lending by western banks even as, since the first oil shock, the OPEC countries increased their financial assets and began massive investments with the Eurocurrency markets.

At the same time, against this broad framework, each of the eight largest U.S. banks (Bankers Trust, Chase Manhattan Bank, Chemical Bank, Citicorp, Irving, Morgan, Manufacturers Hanover, Marine Midland) increased their lending to the three largest Latin American debtor nations: Brazil, Mexico and Argentina.60

Back to topConclusion

The first part of this contribution has pinpointed the late 1960s and early 1970s outflow of short-term financial assets from the United States to the highly unregulated Eurocurrency markets. As pointed out in section 3 this process substantially contributed to the shrinking U.S. balance of payments deficit on the capital account that the United States experienced at the time. Neither U.S. laws devised to revert such capital outflows, nor measures implemented to prop up the current account position, were successful in stabilising either the U.S. balance of payments in the aggregate or the U.S. trade deficit. In the light of this late-1960s striking external imbalance, the U.S. commercial and investment banks got involved in propping up the U.S. balance of payments and in supporting the value of the U.S. currency in the foreign exchange markets in different ways. In so far as the foreign economic and financial assistance programs to the developing nations had an impact on total U.S. balance of payments deficit, this contribution has focused on the U.S. specific strategy devised to lessen such impact of U.S. economic assistance to the non-oil LDCs through full involvement of the American banking system both from the second half of the 1960s to the first oil price hike and later on during the 1970s. In either case, the involvement of American commercial banks was based on the idea that U.S. financial capitalism could contribute to a policy of currency diversification of American development assistance programs out of the dollar intended to ease the ongoing strains of foreign economic assistance on the value of U.S. dollar in the foreign exchange markets. A policy of currency diversification out of the U.S. currency would prop up the dollar by reducing its share in world money supply.61

Section 4 has investigated how American banks got increasingly involved in diversifying the basket of currencies in which the bonds and securities issued by the IBRD to finance its development assistance programs were denominated. The involvement of American commercial banks in the pursuit of this objective was clearly intended to reduce the share of dollar assets in world money supply and to ease the pressure of IBRD official development assistance on the U.S. balance of payments. Measures undertaken by U.S. authorities to forestall the outflow of capital from the United States and the overlapping of multiple developments in the international monetary and energy markets, that occurred from the second half of the 1960s to the beginning of the new decade, were ill-functioning, as highlighted in the first part of this contribution. It led U.S. authorities to get involved further U.S. private capital in trying to ease the pressure of capital outflows on the balance of payments and the standing of the American currency against other major currencies. Along this line of researching, section 5 has explored the continuance of this policy to abate unfettered plunging of U.S. balance of payments and U.S. currency. It did so by resorting to the American banking system in the new international economic environment that followed the first oil price hike. As detailed in section 5, since the first oil crisis a new chain of international investments and borrowings materialized. The first oil price hike triggered a surge in the oil revenues and financial assets of the OPEC oil producers. This surge led Middle Eastern countries to become global investors by massively placing funds with unregulated and highly profitable short-term Eurocurrency markets, most of which were at the time Eurodollars. By the mid-1970s 40 percent of the OPEC countries' international placements were with the Eurocurrency markets, and by year-end 1977 as much as 70 percent of new yearly placements with the Euromarkets came from the OPEC countries.62 More specifically, this process took place through increased OPEC placements with the most important Wall Street banks, which in turn reflowed these assets to their overseas branches specialised in trading in the Eurocurrency markets, and to other international banking institutions that traded Eurocurrency assets.63 During the 1970s at the highest U.S. foreign monetary policy level there was an intensive debate on whether or not the Eurodollars were resident dollars and contributed to money supply and inflation. This debate revolved around a dispute on the Eurodollar as a time deposit or demand deposit.64 Notwithstanding these lengthy debates within the United States on whether or not the Eurodollars could be counted to measure U.S. money supply, since 1974 U.S. authorities relied on Eurodollar and other Eurocurrency markets traded by U.S. commercial banks as a way to finance the non-oil LDCs’ pressing balance of payments deficit and import problems. The United States considered this way a strategy to continue development assistance without further straining the U.S. currency in the foreign exchange markets. All along the decade of the 1970s it was a widely-shared view among U.S. policymakers that U.S. commercial banks could play a critical role in putting Eurodollar and other Eurocurrency assets to finance the LDCs.65 Therefore, dollar-denominated assets accrued to the OPEC countries after the first oil shock were deposited with the Eurocurrency markets. Then, these Eurocurrency assets were traded by the U.S. and other western commercial and investment banks specialised in dealing Eurocurrencies to finance international lending to the non-oil LDCs struck the most by the 1975 recession in Europe on both their current account position and their foreign debt. Along this line of research, section 5 has reconstructed this new pattern of international investments and lending by also providing a quantitative assessment of lending patterns by the largest U.S. banks and other leading commercial banks from before the 1973 oil crisis to the following few years. The outcome is that after the first oil crisis American and European commercial and investment banks shifted their investment and lending activities from Europe and other developed markets to the developing world, and particularly to the Latin American non-oil LDCs. Over the following years and decade these non-oil LDCs suffered the most from the implication of the two oil crises in terms of balance of payments deficit and foreign debt. More specifically, this was the case for the hard currency requirements for import and export-financing that trapped Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina in the lost decade of the 1980s.

- 1. see for instance David E. Spiro, The Hidden Hand of American Hegemony. Petrodollar Recycling and International Markets (Ithaca, NY-London: Cornell University Press, 1999); Susan Strange, Casino Capitalism ( Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2015 [1986]); Alan R. Plotnick, "Third World Oil Problems and American Banks", American Business Review, 1, 1984, 1-7.

- 2. The literature is too vast to summarize here: see for instance Elisabetta Bini, Giuliano Garavini and Federico Romero (eds.), Oil Shock. The 1973 Crisis and Its Economic Legacy (London: IB Tauris & Co, 2016); Charles S. Maier, "Malaise. The Crisis of Capitalism in the 1970s", in Niall Ferguson, Charles S. Maier, Erez Manela and Daniel Sargent (eds.), The Shock of the Global. The 1970s in Perspective (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010), 31 ff.; Daniel Yergin, The Prize. The Epic Quest for Oil, Money and Power (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1991).

- 3. Spiro, The Hidden Hand (cf. note 1).

- 4. on the role of the IMF see Manuel Pastor Jr., "Latin America, the Debt Crisis, and the International Monetary Fund", Latin American Perspectives, vol. 16, n. 1, 1989, 79-110; Raúl García Heras, El Fondo Monetario y el Banco Mundial en la Argentina. Populismo, Liberalismo y Finanzas Internacionales (Buenos Aires: Ediciones Lumiére, 2008); ; Raúl García Heras, "Multilateral Loans, Banking Finance, and the Martinez de Hoz Plan in Argentina, 1976-1981", Revista de Historia Económica-Journal of Iberian and Latin American Economic History, vol. 36, n. 2, 2018, 215-240. Claudia Kedar, "Salvador Allende and the International Monetary Fund 1970-1973: The Depoliticisation and Technocratisation of Cold War Relations", Journal of Latin American Studies, vol. 47, n. 4, 2015, 717-747; Claudia Kedar, The International Monetary Fund and Latin America: The Argentine Puzzle in Context(Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2013): Paul Kershaw, "Averting a Global Financial Crisis: The U.S., the IMF, and the Mexican Debt Crisis of 1976", The International History Review, vol. 40, n. 2, 2018, 292-314; on the case of the IBRD see Sarah Babb, Behind the Development Banks. Washington Politics, World Poverty, and the Wealth of Nations (Chicago, IL-London: The University of Chicago Press, 2009), 102-108, 128 ff.; Patrick Allan Sharma, Robert McNamara's Other Way: The World Bank and International Development (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017), 75-95; Claudia Kedar, "The World Bank Lending and non-Lending to Latin America: The Case of Argentina 1971-1976", Revista de Historia Económica-Journal of Iberian and Latin American Economic History vol. 37, n. 1, 2019, 111-138; on IDA and multilateral banks, much less investigated than the IBRD and IMF, see Christopher G.Locke, Fredoun Z. Ahmadi-Esfahani, "The origins of the International Debt Crisis", Comparative Studies in Society and History, vol. 40, n. 2, 1998, 223-246; see also Guillermo Perry, Eduardo Garcia, "The Influence of Multilateral Development Institutions on Latin American Development Strategies", in Gilles Carbonnier, Humberto Campdónico, and Sergio Tezanos Vázquez (eds.), Alternative Pathways to Sustainable Development: Lessons from Latin America (Boston-Leiden: Brill, 2017), 199-234.

- 5. William R. Cline, International Debt Reexamined (Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics, 1995); Robert Devlin, Debt and Crisis in Latin America. The Supply Side of the Story (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016 [1990]).

- 6. Carlo Edoardo Altamura, European Banks and the Rise of International Finance. The Post Bretton Woods Era. London-New York (Abingdon-New York: Routledge, 2017). For a rather divergent approach focused on the role of private banks from developing countries in reflowing the OPEC nations assets to the LDCs through access to short-term unregulated money markets see Sebastian Alvarez, Mexican Banks and Foreign Finance. From Internationalization to Financial Crisis, 1973-1982 (London: Palgrave Macmillan 2019), 1-31.

- 7. for further details and data on the interlocking relations among these different developments see Simone Selva, Before the Neoliberal Turn. The Rise of Energy Finance and the Limits to US Foreign Economic Policy (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 91-194.

- 8. Division of International Finance of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to the Board of Governors, Office Correspondence "Eurocurrency Reserve Requirements on Loans to U.S. residents by foreign branches of US banks", 30.10.1980, 5, in Federal Reserve Bank of New York Historical Archives, New York City, NY (henceforth FRBNYA), b. 553726, fold. Foreign Lending 1982; see also 95th Congress, 1st Session, Joint Committee Print, Some Questions and Brief Answers about the Eurodollar Market. A Staff Study Prepared for the Use of the Joint Economic Committee Congress of the United States (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1977), 13.

- 9. in 1971 the U.S. balance of trade registered an historical and unprecedented deficit.

- 10. Patrick Allan Sharma, Robert McNamara's Other Way. The World Bank and International Development (Philadelphia, PA: The University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017). Devesh Kapur, John P. Lewis, Richard Webb, The World Bank: Its First Half Century. Vol. 1: History (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 1997); Katherine Marshall, The World Bank. From Reconstruction to Development to Equity (London-New York: Routledge, 2008).

- 11. though in Washington a wide-ranging debate on whether or not the Eurodollars should be counted to measure U.S. money supply, the vast majority of policymakers shared the idea that investing in the Eurodollar markets was a means of currency diversification out of the dollar; as a corollary to this interpretation, as much as any other Eurocurrency market the Eurodollar market was an instrument to contrast the decline of the dollar in the foreign exchange markets.

- 12. The literature on this and other measures signed into law in the 1960s in support for the U.S. capital account position such as the Interest Equalization Tax enacted in 1964 is abundant. On the VFCR Program see Rachel Strauber, "Voluntary Foreign Credit Restraint and the Nonbank Financial Institutions", Financial Analysts Journal, vol. 26, n. 3, 1970, 10-12, 87-89; Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Annual Report 1972 (Washington, DC: Federal Reserve System, 1973), 191-194; See also Carnegie Mellon University Archives, Allan H. Meltzer Papers, Federal Reserve Research, Board of Governors Minutes, b. 43, fold. 23.

- 13. FRBNYA, Paul Meek to Paul Volcker, Office Correspondence "The Euro-banking System: Its Relation to Monetary Policy", 18.08.1978, in FRBNYA, b. 553726, fold. Foreign Lending 1982.

- 14. Norris O. Johnson, Eurodollars in the New International Money Market (New York: First National City Bank, 1964), 8.

- 15. see Morgan Guaranty Trust Co., Business Week, 21.02.1970: monographic issue on "The Money Machine Magic of Eurodollars”.

- 16. FRBNYA, b. 553726, fold. Foreign Lending 1982.

- 17. see unpublished statistical data in Federal Reserve Bank of New York, "Statistical Background Material", 09.08.1976, in FRBNYA, Central Files, b. 616276, fold. Financing Facility OPEC 1974.

- 18. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Annual Report 1974 (Washington, DC: Federal Reserve System, 1975), table A 66.

- 19. UNCTADstat, "Free market commodity price indices, annual, 1960-2010" (price indices 2000=100). Url: http://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/TableViewer/tableView.aspx?ReportId=30… (accessed May 20/5/2015).

- 20. for further details on these events and how they played out in the development of inflationary strains in the international economy see Selva, Before the Neoliberal Turn, 91-194 (cf. note 7).

- 21. on the lengthy discussions on the reform of the international monetary system the literature is abundant. A key reference work is Harold James, International Monetary Cooperation since Bretton Woods (Washington, DC-New York-Oxford: IMF-Oxford University Press, 1996), 228-259.

- 22. Howard M. Wachtel, The Money Mandarins. The Making of a Supranational Economic Order (London: Pluto Press, 1990), 78; James, International Monetary Cooperation since Bretton Woods, 172 (cf. note 21). Graham Bird, The IMF and the Future. Issues and Options Facing the Fund (London-New York: Routledge, 2003), 267 ff.; Christopher Wilkie, Special Drawing Rights (SDRs). The First International Money (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 34 ff.

- 23. see statistical data in OECD, "Development Cooperation Report 1984", 1984, cited and reproduced in Donald R Lessard, John Williamson, Financial Intermediation Beyond the Debt Crisis (Washington, D.C.: Institute for International Economics, 1985), 10.

- 24. R. McNamara, Memorandum for the Record "Switzerland", 15.05.1968, in World Bank Group Archive, Washington, DC (henceforth WBGA), Records of the Office of the President, Records of President Robert S. McNamara, Contacts-Member Countries Files, Contacts with member countries: Switzerland-Correspondence 01.

- 25. IBRD Press Release n. 541, 27.06.1958, "Background Statement", in WBGA, Records of the Office of the President, Records of President Eugene R. Black, President Eugene R. Black Papers-Congratulations Correspondence-Volume 6-1953, 1958.

- 26. WBGA, Records of President Eugene Black, (cf. note 25).

- 27. The Staff of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, "Current Economic and Financial Conditions. Prepared for the Federal Open Market Committee", 27.01.1965, III-8, in National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD (henceforth NARA), Record Group 82, General Records of the Federal Reserve System, (RG82), Division of International Finance and Predecessors, International Subject Files 1907–1974, b. 327.

- 28. Memorandum of Conversation Lipfart-Schneider-Schmidt-Anders-Aldewereld, 10.06.1968, in WBGA, Records of the Office of the Presidents, Records of President Robert S. McNamara 1968, Correspondence with Member Countries: Germany. Correspondence 01, fold. Contacts Germany 1968.

- 29. National Advisory Council Alternates Meeting Minutes, Meeting 75-1, "Review of IBRD/IDA Program and Financial Policies", 16.01.1975, in NARA, Record Group 56, General Records of the Department of the Treasury (henceforth RG56), National Advisory Council on International Monetary and Financial Policies (henceforth NAC), NAC Alternates Minutes and Agenda, NAC Principal Minutes and Agenda, NAC Steering Committee Minutes, NAC Semi Annual Debt Review 1971–1975, b. 1, fold. NAC Alternates-Minutes, Meeting N. 75-1 through Meeting N. 75-8, 16.01.1975–3.12.1975; Sir Denis Rickett (IBRD Vice President), “The Provision of Additional Resources to Developing Countries and the Respective Role of the Fund and the Bank”, undated, in WBGA, Records of General Vice Presidents and Managing Directors, Records of Sir Denis Rickett, Oil and Energy, Memos and Reports 1973 through 1974, Volume 3.

- 30. W.L. Bennett to Mr. Clark, Memorandum “Summary of New York Visits. October–November 1968”, in Library of Congress, Washington, DC (henceforth LOC), Manuscript Division, Robert McNamara Papers, Part 1, b. 21, fold. 1 (Bennett, William Memoranda of McNamara Trips 1968–1971).

- 31. William Bennett to Mr. Clark, Memorandum “Visit to New York City––March 1969”, in LOC, Manuscript Division, R. McNamara Papers, Part 1, b. 21, fold. 1 (Bennett, William Memoranda of McNamara Trips 1968–1971).

- 32. Memorandum of Conversation McNamara-Aldewereld-Guth-Klasens, 06.06.1968; Memorandum of Conversation Dr. Henkel-Mr. Aldewereld, 07.06.1968; Memorandum of Conversation Lipfort-Schneider-Schmidt-Anders-Aldewereld, 10.06.1968: all these documents are located in WBGA, Records of the Office of the Presidents, Records of President Robert S. McNamara 1968, Correspondence with Member Countries: Germany. Correspondence 01, fold. Contacts Germany 1968.

- 33. John Morrian to Robert McNamara, Office Memorandum, “R. McNamara interview with Douglas Ramsey, Economic Development and Raw Material Correspondent of the Economist", 28.07.1975; Office Memorandum “Meeting with Chancellor of the Exchequer, October 1, 1974 (present: McNamara, Denis W. Healey , Derek Mitchell, Richardson, Wass, Rawlinson, France, Cargill)”, 02.10.1974, in WBGA, Records of the Office of the President, Records of President Robert S. McNamara, Contacts with Member Countries: United Kingdom, General Correspondence 03.

- 34. W.M. Van Saagevelt to Mr. D. Love, “Memorandum on the Bank Group's Relationship with the United Kingdom”, 11.08.1967, in WBGA, Records of the Office of the President, Records of President Robert S. McNamara, Contacts with Member Countries: United Kingdom, General Correspondence 02.

- 35. See respectively Summary Memorandum of Conversation D.S. Rickett-R. McNamara-The Governor of the Bank of England), “Annual Meeting 1968––United Kingdom”, 09.10.1968; and D.S. Rickett (IBRD Vice President), “Annual Meeting 1969. Meetings with Governors of Part I Countries. United Kingdom”, 24.09.1969, both in WBGA, Records of the Office of the President, Records of President Robert S. McNamara, Contacts with Member Countries: United Kingdom, General Correspondence 01 (1968–1969).

- 36. Memorandum of Conversation McNamara-Aldewereld-Lipfart (GiroZentrale), 06.06.1968; Memorandum of Conversation McNamara-Aldewereld-Guth-Kalusens (Deutsche Bank), 06.06.1968, in WBGA, Records of the Office of the President, Records of President Robert S. McNamara, Contacts with member countries: Germany––Correspondence 01, fold. Contacts Germany (1968).

- 37. Irving Sigmund Friedman, The Emerging Role of Private Banks in the Developing World (New York: Citicorp, 1977), statistical appendix, table 2.

- 38. on the SDRs see Wilkie, Special Drawing Rights (cf. note 22); Onno de Beaufort Wijnholds, Gold, Dollar and Watergate. How a Political and Economic Meltdown was Narrowly Avoided (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), 56-58; Michael Bordo, Harold James, "Reserves and Baskets", National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Papers n. w17492, 2011; Selva, Before the Neoliberal Turn, 112 ff (cf. note 7).

- 39. Interim Committee of the Board of Governors of the International Monetary System, Meeting N. 10, 09.08.1978, Mexico City, "Record of Discussion", in NARA, RG56, Office of the Assistant Secretary for International Affairs (henceforth OASIA), Office of the Deputy to the Assistant Secretary for International Affairs, Records Relating to International Financial Institutions 1962-1981, b. 6, fold. IM-9-2 International Monetary Jan-Aug International Monetary System.

- 40. Eugene Black to Jack Bennett (Undersecretary for the Treasury for Monetary Affairs), 21.03.1975, in Rockefeller Archive Center, Tarrytown, NY (henceforth RAC), Nelson A. Rockefeller Vice Presidential Central Files, Record Group III 26 3, b. 167, fold. FI9.

- 41. for these data see R.Reisch (Fed New York Foreign Research Division) to Davis, "The U.S. Plan for Recycling Oil Funds", 02.12.1974, in FRBNYA, b. 616276, fold. Financing Facility OPEC 1974.

- 42. D.Beek, "OPEC lending to Official and Semi-Official Entities", 29.07.1975; P.Fousek to P.Volcker, Office Correspondence, 29.07.1975, in FRBNYA, b. 616276, fold. Financing Facility- OPEC 1974.

- 43. Eugene Black, "The Less Developed Countries Payment Deficits. A Plan to Help", 20.10.1976, in FRBNYA, b. 616276, fold. Financing Facility-OPEC 1974.

- 44. these figures are based on a Federal Reserve Bank of New York study by David Beek, "The External Debt Position of the non-oil Developing Countries", 28.10.1976, in FERBNYA, b. 616276, fold. Financing Facility- OPEC 1974.

- 45. Talk by Abdullatif Al-Hamad, Director General of the Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development "Problems of Aid and Lending", Harvard University, 25.04.1977, in FRBNYA, b. 616276, fold. Financing Facility OPEC-1974.

- 46. see for instance the involvement of Chase Manhattan Bank and First National City Bank in Iran: Memorandum of Conversation C.Widney (Representative of Chase Manhattan Bank)-the U.S. Ambassador in Iran "Chase Manhattan activities in the Middle East", 31.10.1968; R.Harlan (U.S. Embassy in Teheran) to W.McClelland (U.S. Department of State), 30.07.1968, both documents in NARA, General Records of the Department of State (RG59), Bureau of Near Eastern and South Asian Affairs, Office of the Iran Affairs, Records Relating to Iran 1965-1975, b. 3.

- 47. D.Keyser to T.Willet, Memorandum "Recycling Petrodollars: Aspects of Financial Market Behavior", 23.09.1974, in NARA, RG56, OASIA, Office of the General Counsel. Assistant General Counsel, Records Related to OPEC Financial Affairs 1974-1979, b. 8; see also The Financial Times, 24.09.1974.

- 48. E. Black to J. Bennett (Undersecretary of the Treasury for Monetary Affairs), 21.03.1975, in RAC, RG III, 26, 3, Nelson A. Rockefeller Vice Presidential Central Files, b. 167.