The World Energy Council as an archive for research on energy history

University of Bielefeld / University of Toronto and University of Guelph

daniela.russ[at]uni-bielefeld.de ou daniela.russ[at]utoronto.ca

Twitter : @ueberdruss

This paper presents the World Energy Council (WEC) as an archive for research on the history of energy. Since its foundation in 1924, this non-governmental, technical, international organization, organized more than thirty congresses and meetings, published numerous proceedings, statistics, and reports and conducted a couple of major studies and surveys in the field of energy. Stretching over almost one hundred years and covering all technical forms of energy, the WEC constitutes a unique archive for researching energy history today. The purpose of this paper is, firstly, to provide an overview of the variety of material produced by the World Energy Council. Secondly, I identify ways in which historical scholarship can approach this material and benefit from it. Drawing on the experience of textual analysis in the social sciences, the paper distinguishes four approaches. The documents can be approached as a (1) source of information for the history of energy, or be seen as (2) strategic interventions in a debate. Moreover, they can become the basis for an (3) archaeology of knowledge focusing on how they came to be authoritative statements in a discourse on energy. Lastly, they can serve to explore (4) the relation between the making of documents and their function in a discourse.

The World Energy Council (WEC)1 is a non-governmental, technical, international organization in the field of energy. In 1924, Daniel N. Dunlop, a British electro-technical engineer and director of the British Electrical and Allied Manufacturer's Association (BEMA), initiated the first World Power Conference in the wake of which the organization was founded. Since that time, the WEC has organized more than thirty congresses and meetings, published numerous proceedings, statistics, and reports and conducted a couple of major studies and surveys. Stretching over almost one hundred years and covering all technical forms of energy, the WEC makes for a unique archive for energy history. The main aim of this paper is, firstly, to provide a brief overview of the variety of material – publications and administrative documents – produced by the World Energy Council over the course of the last century. In a second step, I identify ways in which historical scholarship can approach and draw from this material. This paper does not provide a comprehensive overview; instead, I understand this as the beginning of a more systematic approach towards the documents published by the WEC.

Scholars working in the field of energy history have likely come across the World Energy Council at some point in their research; they might even have worked with WEC publications. In general, however, historical research has tapped the WEC archive only in a selective and unsystematic manner. One challenge in using WEC documents is that the use of primary sources in historical research requires their critical assessment: who created them, by which means, and for which purpose? However, scholarly work on the WEC as such –its organizational structure, decision making procedure, and its various activities– is still very limited. The two histories on the WEC have been commissioned by the organization itself on occasion of its anniversaries.2 Wright, Shin and Trentmann’s From World Power Conference to World Energy Council stands out for how well it embeds the organizational history in the broader historical context. Elsewhere, I have tried to complement these works with a view on the emergence of a global energy economy.3

In the following, I give an introduction to the various documents that have been produced by the WEC over the last century. As the largest and longest-ranging series of publication, I focus particularly on conference proceedings and digests. Along with this overview, I provide a table on Github (https://github.com/Ueberdruss/World-Energy-Council), which gives the date and topic of the conferences, their table of contents, and information on where they can be accessed. In the second part of this paper, I identify the scope of topics and research questions that can be addressed on the basis of the variety of material published by the WEC by analytically distinguishing four approaches. I conclude that further research on organizational practice, including interviews, would be helpful to situate the documents and understand their origins.

Back to topThe Variety of Publications

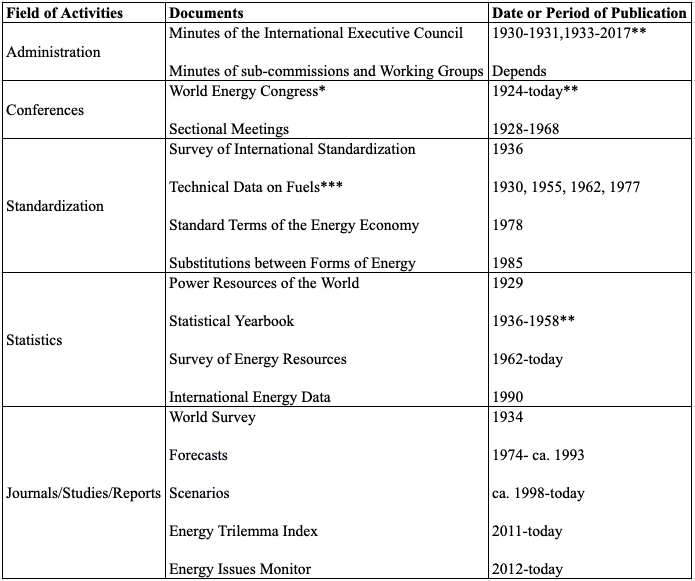

Over the last century, the WEC has published a broad range of material that differs widely in form and content (see Table 1).

Three of the publications cover almost the entire period of time: the conference proceedings, the minutes of the International Executive Council (IEC, the WEC’s authoritative body, which meets annually), and the statistical survey on power resources. Other publications were temporarily limited, such as surveys on standardization, the results and minutes of sub-commissions and working groups, or the short-lived journal World Survey. Recently, the WEC began publishing an annual ranking of energy policy performance, the Energy Trilemma Index, and the Energy Issues Monitor –a publication that seeks to feel the pulse of the ‘global energy economy’.

Even though the WEC was renamed World Energy Council in 1992 to highlight its broad range of activities, the organization of the World Power Conferences (now ‘congresses’), remains the core of the WEC’s activities. It is the only time when the organization makes it into the news, and many of the organizational activities are structured around and geared towards the rhythm of the conferences. In the beginning, there were two types of conferences: World Power Conferences and Sectional Meetings. Sectional Meetings were regionally or thematically limited gatherings, which had initially been introduced to “keep up the interest” between the full conferences taking place only once every six years.4 In 1968, Sectional Meetings were abolished and full conferences began to be organized in a more standardized fashion every three years.5 The early conference proceedings came in few, heavy volumes, resembling other documentations of scientific conferences. In the mid-20th century, the WEC experimented with multiple, smaller volumes that could be purchased separately, but still included every single conference paper. It was only in the 1970s that conferences were beginning to be documented in digests, roundups or chronicles –focusing on the glaring moments and ‘factual’ outcomes.6

These changes in publication form are interesting in themselves from a media-historical point of view (the discussions touch upon printing costs and technology, the wider circulation of smaller volumes and digests, etc.). However, they also affect the ways in which the conference proceedings can inform historical research. Where full technical papers are given, the proceedings can complement studies in the history of electrification, technology and energy politics. Protagonists that have long been at the heart of national histories of electrification, such as Herbert Hoover, Samuel Insull, Georg Klingenberg, and Aleksandr Kogan, presented at the early conferences. Digests, in contrast, reflect a primacy of organization over individual contributions. They were put together with a view on the entire conference and the intervention the WEC –or the National Committee organizing the meeting– intended to make in a more general discussion. Digests mark the turn from a scientific conference to an organization representing an ever more self-aware industry. From this follows that technical papers, welcoming speeches, and discussions, are comparable to a different degree over the entire period of time.

The second series of publications ranging from the earliest years of the organization until today are the statistics on energy resources, published as Statistical Yearbook of the World Power Conference from 1936-1958, and as Survey of Energy Resources from 1962-today. From its foundation, the WEC strove to become a “center of calculation”7 for a world power (later: energy) economy. The idea was pervasive in Dunlop’s early plans for the organization and translated into a durable focus on resource statistics. Between 1936 and 1958 the WEC had published nine issues of the Statistical Yearbook. However, when the United Nations began to issue its “J” series of Statistical Papers in 1952, the WEC reviewed its statistical work to avoid overlap between the two publications. Starting from 1962, the new publication called the Survey of Energy Resources focused solely on resources and – as this information was more long-lived – was issued only once every six years. In the 1970s, the rhythm of publication was synchronized again with the triennial rhythm of World Energy Congresses.

Another long-term form of documentation are the minutes of the WEC’s International Executive Council (IEC). These are not officially published, but can be accessed through the WEC London Headquarters. The minutes are available for almost the entire period from 1930-2017, with only minor exceptions (see Table 1). Like with other publications, the form of the minutes –their structure, layout, and print– changes over the time, reflecting waves of rationalization and professionalization of the organization. The minutes give information on attendance, speakers, topics, and decisions. Thus, they are especially interesting to study the WEC’s own organizational history, as well as its relation to corporations, industries, and (inter)national administration.

Starting from the 1970s, the WEC complemented its two major publications –the conference proceedings and resource statistics– with more project-based brochures and reports. There had always been temporally limited publications, such as the short-lived journal World Survey (1935), a report on Power Resources of the World (Potential and Developed) (1929), a Survey of National and International Standardization (1936), or the handbook Substitutions between Forms of Energy and How to Deal with Them Statistically (1985) published in cooperation with the Union Internationale des Producteurs et Distributeurs d’Energie Electrique (UNIPEDE). Beginning in the 1970s, the WEC began to organize its work in sub-commissions and working groups. Through the work of the Conservation Commission set up in the wake of the oil crises in 1975, the WEC became for the first time involved in actual studies of the ‘energy economy’. The forecasts and energy balances worked out in this commission were published in three reports, World Energy: looking ahead to 2020 in 1979, Energy 2000-2020: World Prospects and Regional Stresses in 1983, and World Energy Horizons (2000-2020) in 1989. The Conservation Commission turned into the Study Commission in the 1990s; around 2000 its focus shifted from forecasting to scenario-building.

Recently, the WEC initiated two new surveys that are published in short annual reports: The Energy Trilemma Index and the World Energy Issues Monitor. The Energy Trilemma Index ranks countries according to their performance in three dimensions of the ‘energy challenge’: energy security, energy equity, and environmental sustainability. Apart from the annual reports, there is also an interactive online tool that makes the ranking’s variables transparent.8 The World Energy Issues Monitor, in contrast, is an annual survey among public officials, chief executives and ‘leading experts’ conducted in the WEC member countries.9 These experts give their views on the ‘world energy agenda’, focusing on “macroeconomic risks; geopolitics; business environment; and energy vision and technology”.10 The Issues Monitor can also be tailored to match the informational needs of specific industries or regions.11

While covering the most important projects, this overview of the WEC’s publications is incomplete in two ways. Firstly, the WEC embarked on many different study projects with various cooperation partners, often focusing on a specific industry or problem and resulting in single reports. Not all of these reports have been mentioned here. Secondly, the activities of the national committees are not taken into account here, even though they undertook their own studies and reports.

Back to topThe Scope of Topics and Research Questions

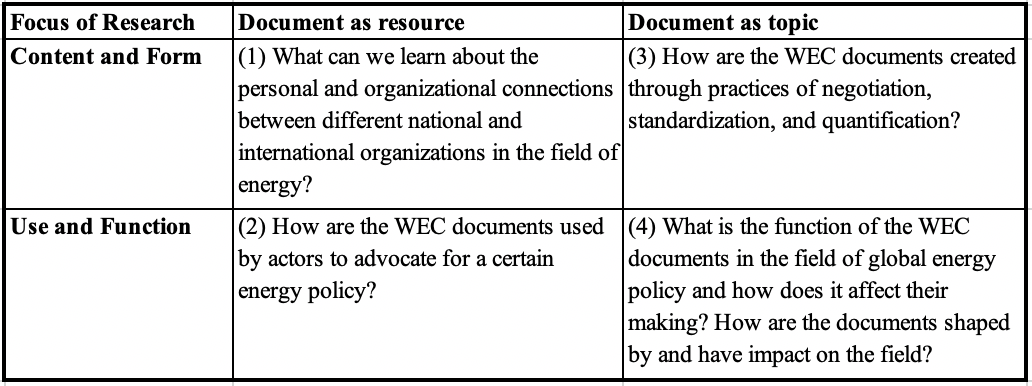

What kind of questions can be asked on the basis of the WEC’s documents and what is the scope of research topics that can be addressed? Understanding texts not merely as a source of information, but as discursive documents, shaped by and intervening in a discourse on energy, the WEC’s documents can inform very different research questions. Drawing on Lindsay Prior’s (2008) categorization of textual material in social research, I lay out four ways in which the WEC documents can be approached (see Table 2).12 Prior distinguishes on the one hand between the form and content of a document, as well as its use and function. On the other hand, documents can be understood as a mere source of information, or a ‘topic’ themselves. Treating documents as ‘topics’ means to investigate their own making. Documents, in other words, can become a research object in their own right. Drawing from Prior’s distinctions, the WEC’s documents can (1) be seen as a source of information and (2) a source through which we can learn about the strategic use or function of the publication. What is more, they can become the material of (3) a more ‘archaeological’ endeavor to study how their specific content came into being. (4) Lastly, we can extend this approach to the use of these documents, asking about their specific function in the discourse.

Documents as Source of Information

Most of the above-mentioned documents published by the WEC are intended to give information on some aspect of the ‘world energy economy’. Insofar as historical research is interested in precisely this information, such as historical data on resources, numbers on national energy supply and consumption, or the state of international standardization etc., the documents can be used as a source of information in a straightforward way. However, assessing the accurateness of the information is not always so simple.13 Apart from the information the WEC's documents are supposed to give, they contain plenty of by-information that can become valuable in historical and sociological research. To give an example, a thorough analysis of different WEC documents could inform a history of how an international network of energy politics emerged. Most conference proceedings give information on the speakers, their country of origin and organizational affiliation. The minutes of the IEC also provide a list of attendees (and their status) and document all contributions to a discussion. Since the second half of the 20th C., delegates of international organizations regularly take part in the meetings, without being official WEC members. In turn, WEC delegates represent the organization at the meetings of other international organizations. So, in principle, these documents allow to trace the personal and organizational links between several organizations in the field. While some of the involved organizations have received scholarly attention, they have never been studied with a focus on their personal and organizational interrelations.14 By combining these archives, the emerging network of international energy politics could be traced from the time of the League of Nations, through the post-war organizations of economic recovery, the United Nations regional organizations and technical assistance program, to the institutions set up during the oil crisis of the 1970s.

The Function and Strategic Use of Documents

The WEC always claimed to be a clearing house for energy information, and a platform to exchange experiences between people working in the ‘field of energy’.15 Neither representing the interests of a particular nation nor industry, the organization declared itself neutral. However, this is not to say that the organization's documents cannot be studied as strategic interventions in a political debate. In the 1930s, for instance, the WEC developed a position toward international standardization, which is mirrored in the form and content of its publications. An even better example is the WEC’s reaction to the oil crises of the 1970s. Having both oil-consuming and oil-producing countries among its members, the WEC found itself in a peculiar position. The political conflict around national sovereignty and petroleum prices became apparent at the World Energy Congress in Detroit in 1974 and the Congress in Istanbul three years later. The foundation of the Conservation Commission in 1975, the sub-commission that would over the following decades become an important part of the WEC’s activities, was a direct reaction to the renewed interest in research on energy economics following the oil crisis. Even though the commission was initially encouraged by the OECD, and the Western nuclear industry had a firm foothold in the commission, it diversified over the years and included members from Eastern Europe and OPEC countries as well. The reports were intended to put forth a global perspective on energy security, going beyond both the International Energy Agency's and the OPEC’s statistical work.16

An Archaeology of Knowledge on Energy

The WEC's history ranges across almost an entire century. Over this period of time, knowledge on energy changed profoundly with the organizations, professions and methods involved in its making. Thus, the material published by the WEC enables a history or sociology of knowledge, an archaeology of knowledge, or historical epistemology.17 Such an investigation can take on many forms. It can focus on the practices of standardization, the conflicts and negotiations, or resources, technologies and markets shaping and being shaped by knowledge.18 From its very beginning, the WEC cherished international understanding among engineers and technicians. While it never acted as a standardizing body, it sought to influence the standard setting procedures of other international bodies, such as the International Organization for Standardization (ISO, formerly ISA), the International Electrotechnical Commission, or the UNIPEDE. Moreover, it required a certain degree of standardization of terms and units for internal understanding. One of the longest discussions centered around the concept of ‘resources’ as it was used in the Statistical Yearbook and later the Survey of Energy Resources. An archaeology of knowledge of the resource concept would shift attention to its form –the rules according to which something appears as a resource– and relation to the industries, professions and groups using it. Such an approach could reveal both processes of standardization (of methods, instruments, and units) and changes in the organizational, technological, and professional ‘landscape’ of knowledge on energy (from a more geological to a more economic determination of resources). Covering together almost one hundred years of statistical information and methodological knowledge, an analysis of the Statistical Yearbook and the Survey of Energy Resources, as well as the respective discussions in the IEC, could inform such an undertaking.

The Interaction of Documents and Discourses

In recent decades, the WEC shifted towards more frequent and more policy-oriented publications. Rather than ‘publications’ on a topic, they should be understood as more performative documents, as they explicitly seek to ‘set an agenda’, to make a contribution to a debate and inform policy choices, or to provide ‘actors’ in the field with a map to guide their decisions. As such, these documents do not just display knowledge whose making can be studied, but they intervene in the so-called field of energy in a regular manner. They claim to ‘represent’ a state of the field, while at the same time being shaped by the WEC’s position in the network of international and national organizations providing information on resources and energy policy. The Energy Trilemma Index and the Energy Issues Monitor are the most apparent examples of this new publication strategy, which started with a major organizational restructuring in the 1990s. These publications lend themselves to a fourth approach –one that combines their broader function in a discourse with their making through processes of standardization and negotiation.

Back to topConclusion

The WEC makes for a unique archive for energy history for three reasons. Firstly, it covers a period of almost one hundred years with various forms of publications. Secondly, the documents mirror the most significant debates affecting many different industries, such as international standardization, public or private ownership, or the conflict between market and planning approaches in energy policy. Thirdly, in contrast to many other archives in the history of energy, it brings together many different industries and allows to study their changing relations over the time. In other words, the WEC’s publications document the emergence of an interconnected field of energy. However, in order for historical research to make use of this material, the role of the WEC in the international field of energy politics, as well as the internal making of the documents have to be studied in greater detail. Thus, this paper is not only a call to explore the history of energy, but also the World Energy Council, through the analysis of its manifold publications.

- 1. The organization changed its name twice from World Power Conference to World Energy Conference in 1968 and to World Energy Council in 1992. Throughout this paper I use only its current name – World Energy Council.

- 2. Rebecca Wright, Hiroki Shin and Frank Trentmann, From World Power Conference to World Energy Council: 90 Years of Energy Cooperation, 1923-2013 (London: World Energy Council, 2013). Ian Fells and World Energy Council, World Energy 1923-1998 and Beyond: A Commemoration of the World Energy Council on Its 75th Anniversary (London: World Energy Council, 1998).

- 3. Daniela Russ, “Speaking for the World Power Economy: Electricity, Energo-Materialist Economics, and the World Energy Council (1924-1978)”, The Journal of Global History, vol. 15, n°2, 2020.

- 4. Polytechnische Schau: Weltkraftkonferenz, Polytechnisches Journal, n° 340, 1925, 200-1. Url: http://dingler.culture.hu-berlin.de/article/pj340/ar340058 (13/11/2019).

- 5. World Energy Conference, Minutes of the Meeting of the International Executive Council, 1969, Annex 8.

- 6. By focusing on the documentation of the conferences in text, I omit two aspects that would also be interesting for historical research. Firstly, many proceedings contain photographic documentation of the conference highlights, the opening and closing session, dinners and excursions. Secondly, the conferences were often accompanied by excursions to the most notable sights of the ‘energy economy’, i.e. dams, power plants, mines, etc. in the respective countries. At some occasions, there was an exhibition of the ‘national’ power technology along with the conference. I did not come across any substantial documentation of these travels or exhibitions (some of the proceedings include a few pages), but I assume there could be more to find with the National Committees organizing the respective conference. For a brief overview of the conferences and excursions see Fells and World Energy Council, World Energy 1923-1998 and Beyond.

- 7. Bruno Latour, Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers Through Society (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987).

- 8. World Energy Council, Energy Trilemma Index. Url: https://trilemma.worldenergy.org/#!/energy-index (accessed 13/11/2019).

- 9. World Energy Council, World Energy Issues Monitor: Managing the grand transition, 2019. Url: https://www.worldenergy.org/publications/entry/world-energy-issues-moni… (accessed 13/11/2019).

- 10. World Energy Council, World Energy Issues Monitor: What keeps energy leaders awake at night?, 2014, 7. Url: https://www.worldenergy.org/assets/downloads/World-Energy-Issues-Monito… (accessed 13/11/2019).

- 11. Ibid.

- 12. Lindsay Prior, “Repositioning Documents in Social Research”, Sociology, vol. 42, n°5, 2008, 821–36.

- 13. Nowadays, however, the most important sources for energy information are the International Energy Agency and BP Energy Statistics. When WEC data is used and compared to or combined with data from other sources, it should also be taken into account, that the units, conversion factors and statistical methodology applied differs between different organizations.

- 14. Tim Büthe, “Engineering Uncontestedness? The Origins and Institutional Development of the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC)”, Business and Politics, vol. 12, n°3, 2010. Vincent Lagendijk, Electrifying Europe: The Power of Europe in the Construction of Electricity Networks (Amsterdam: Aksant Academic Publishers Transaction Publishers, 2009). Thijs Van de Graaf and Dries Lesage, “The International Energy Agency after 35 Years: Reform Needs and Institutional Adaptability”, The Review of International Organizations, vol. 4, n°3, 2009. Richard Scott and International Energy Agency, The History of the International Energy Agency, 1974-1994: IEA, the First 20 Years (Paris: OECD/IEA, OECD Publications and Information Centre, 1994). Giuliano Garavini, The Rise and Fall of OPEC in the Twentieth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).

- 15. Wright, Shin and Trentmann, From World Power Conference to World Energy Council, 9 (cf. note 2).

- 16. See for the main reports of the Conservation Commission World Energy Conference (ed.), World Energy: Looking Ahead to 2020 (Guildford: IPC Science and Technology Press, 1978). Jean-Romain Frisch, Energy 2000-2020: World Prospects and Regional Stresses: Report (London: Graham & Trotman, 1983). Jean-Romain Frisch and World Energy Conference, World Energy Horizons, 2000-2020 (Paris: Editions TECHNIP, 1989).

- 17. Michel Foucault, Archaeology of Knowledge (London: Routledge, 2010). Michel Foucault, The Order of Things. An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (London: Routledge, 2002). Hans-Jörg Rheinberger, On Historicizing Epistemology: An Essay (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2010). Thomas A. Stapleford, “Historical Epistemology and the History of Economics: Views Through the Lens of Practice”, Research in the History of Economic Thought & Methodology, vol. 35A, 2017.

- 18. Daniela Russ, “Working Nature: A Historical Epistemology of the Energy Economy” (Ph.D diss., University of Bielefeld, 2019).

Büthe Tim, “Engineering Uncontestedness? The Origins and Institutional Development of the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC)”, Business and Politics, vol. 12, n°3, 2010, 1–62.

Fells Ian, World Energy Council, World Energy 1923-1998 and Beyond: A Commemoration of the World Energy Council on Its 75th Anniversary (London: World Energy Council, 1998).

Foucault Michel, Archaeology of Knowledge (London: Routledge, 2010).

Foucault Michel, The Order of Things. An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (London: Routledge, 2002).

Frisch Jean-Romain, Energy 2000-2020: World Prospects and Regional Stresses: Report (London: Graham & Trotman, 1983).

Frisch Jean-Romain, World Energy Conference, World Energy Horizons, 2000-2020 (Paris: Editions TECHNIP, 1989).

Garavini Giuliano, The Rise and Fall of OPEC in the Twentieth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).

Van de Graaf Thijs, Lesage Dries, “The International Energy Agency after 35 Years: Reform Needs and Institutional Adaptability”, The Review of International Organizations, vol. 4, n°3, 2009, 293–317.

Lagendijk Vincent, Electrifying Europe: The Power of Europe in the Construction of Electricity Networks (Amsterdam: Aksant Academic Publishers Transaction Publishers, 2009).

Latour Bruno, Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers Through Society (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987).

Polytechnische Schau: Weltkraftkonferenz, Polytechnisches Journal, n° 340, 1925, 200-1. Url: http://dingler.culture.hu-berlin.de/article/pj340/ar340058 (accessed 13/11/2019).

Prior Lindsay, “Repositioning Documents in Social Research”, Sociology, vol. 42, n°5, 2008, 821–36.

Rheinberger Hans-Jörg, On Historicizing Epistemology: An Essay (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2010).

Russ Daniela, “Working Nature: A Historical Epistemology of the Energy Economy” (Ph.D diss., University of Bielefeld, 2019).

Russ Daniela, “Speaking for the World Power Economy: Electricity, Energo-Materialist Economics, and the World Energy Council (1924-1978)”, The Journal of Global History, vol. 15, n°2, 2020.

Scott Richard, International Energy Agency, The History of the International Energy Agency, 1974-1994: IEA, the First 20 Years (Paris: OECD/IEA, OECD Publications and Information Centre, 1994).

Stapleford Thomas A., “Historical Epistemology and the History of Economics: Views Through the Lens of Practice”, Research in the History of Economic Thought & Methodology, vol. 35A, 2017, 113–45.

World Energy Conference, Minutes of the Meeting of the International Executive Council, 1969, Annex 8.

World Energy Conference (ed.), World Energy, Looking a Head to 2020. Report by the Conservation Commission of the World Energy Conference (Guildford: Published for the World Energy Conference by IPC Science and Technology Press, 1978).

World Energy Council, World Energy Issues Monitor: What keeps energy leaders awake at night?, 2014, 7. Url: https://www.worldenergy.org/assets/downloads/World-Energy-Issues-Monitor-2014.pdf (accessed 13/11/2019).

World Energy Council, World Energy Issues Monitor: Managing the grand transition, 2019, Url: https://www.worldenergy.org/publications/entry/world-energy-issues-monitor-2019-managing-the-grand-energy-transition (accessed 13/11/2019).

World Energy Council, Energy Trilemma Index, Url: https://trilemma.worldenergy.org/#!/energy-index (accessed 13/11/2019).

Wright Rebecca, Shin Hiroki, Trentmann Frank, From World Power Conference to World Energy Council: 90 Years of Energy Cooperation, 1923-2013 (London: World Energy Council, 2013).