From the can to the pump: the sale of petrol in the provinces and its contestation (Côte-d’Or, 1877-1939)

Université de Bourgogne

timo.dhotel[at]gmail.com

Twitter : @TimotheeDhotel

English Translation of "Du bidon à la pompe : la vente du pétrole en province et ses contestations (Côte-d’Or, 1877-1939)" by Arby Gharibian. Original French version available here

This article sheds light on the arrival of petroleum in France, and more specifically in the Côte-d’Or department. While the first barrels were imported in 1861 to the Normandy coast, the earliest trace of a petroleum depot in this rural department surrounding the city of Dijon did not appear until 1877. By 1939 there were approximately 960 of them. This growth, driven by the use of lamp oil and especially by demand for fuel in connection with the rise of the automobile, is one example of “petrolisation,” which although undeniable was nonetheless contested. The conflicts surrounding requests for such installations document a social and environmental history of petroleum, which can be written from the viewpoint of local actors (residents and vendors), in contact with oil companies and the State.

Introduction

“There are provincial towns where people would smash the windows of vendors who dared to post the sale of petroleum without disguising it under the name of luciline, saxoline, or some other euphemism [...] For the Americans that it enriches, petroleum is a gift from above; for the French that it sets ablaze, it’s a product from hell.”1

In 1872, Albert Dupaigne, the holder of an agrégation in physics, expressed the fears that the French harboured toward petroleum, an illuminating oil that remained poorly understood, and that was perceived by some as dangerous. Petroleum vendors crystallized these concerns at the time, and were at the heart of strong tensions, particularly in the provinces. By retracing the history of these sellers at the turn of the twentieth century, it is possible to recount a different history of petroleum, one that is told from the viewpoint of individuals, and in touch with the daily practices connected to this new energy.

Before serving as fuel for our automobiles, petroleum was initially used as an illuminant, and referred to as “huile de pétrole” (petroleum oil) or pétrole lampant (lamp oil). It was in this first form that the fuel was sold beginning in the 1860s by grocers and hardware stores. Relatively affordable, lamp oil was essentially used in private settings in the countryside and non-industrialized countries, while illuminating gas was used in the cities of industrial countries for public lighting.2 “L’essence de pétrole” (essence of petroleum), which was more volatile and inflammable, was deemed too dangerous and often discarded, before having its use revolutionized by the combustion engine. At the time, the sale of fuel was increasingly associated with automobile mechanics and repairmen; it is only beginning in the interwar period that traces can be found for the first “stations de ravitaillement” (supply stations) and later “stations-service” (service stations), which tended to professionalize the distribution of petrol. A number of other derivatives from crude oil had existed since the nineteenth century, such as vaseline.3 However, the uses of these products were secondary, or only required small quantities of petroleum, and therefore this study will essentially focus on petroleum for lighting and fuel.

The sale of petroleum in France firstly required its import. As French production of petroleum was insufficient, French companies were forced to rely on export countries.4 Barrels of crude oil arrived by sea or rail, and were dispatched to French refineries, located primarily near coasts or in the Paris area.5 Once the petroleum was refined, it was distributed across the country—by horses, wagons, barges, and later tankers—to warehouses or storage sites, which served as intermediary storage facilities generally located near cities, with a storage capacity up to 10,000 m3 for hydrocarbons at the end of our period. Petroleum was finally delivered to depots for retail sale, which were numerous, located near residential areas, and stored small quantities of petroleum.

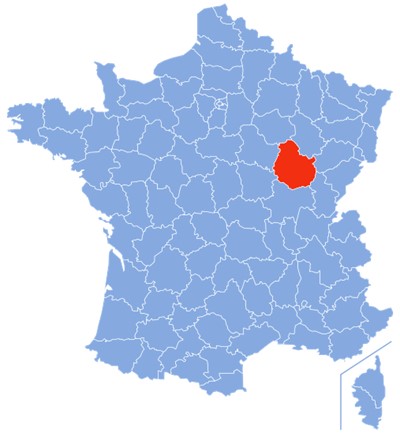

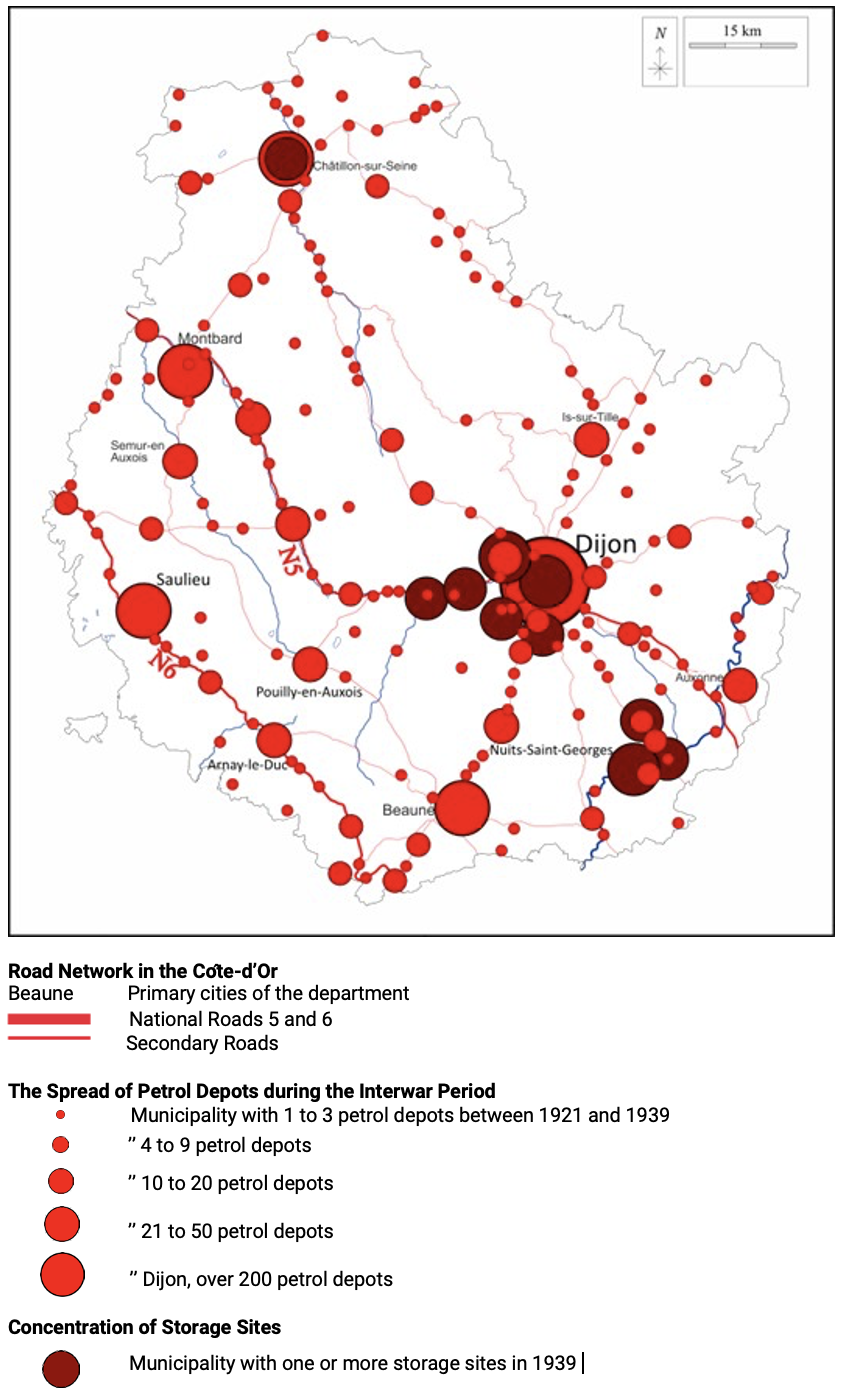

Petroleum depots were unevenly concentrated across France. While the first barrels were stored in the Paris area or the Havre as early as the 1860s, traces of a petroleum depot in the Côte-d’Or (fig. 1) only date back to 1877. This Burgundy department was relatively well connected to the rest of the territory, and the capital in particular, thanks to its navigable waterways, as well as its road and rail networks.6 The diffusion of petroleum barrels could therefore have occurred more quickly than other isolated areas. In addition, one of the distinctive features of the Côte-d’Or was the huge gulf between its prefecture of Dijon—a “bourgeois and merchant city”7 that industrialised thanks to its position as a railway hub, and to the dynamism of a few specialized industries8—and the rest of the territory, which was largely rural and agricultural despite a few medium-sized cities. This gap can also be measured demographically, as the department decreased from 382,000 to 350,000 inhabitants between 1881 and 1911,9 while Dijon experienced full demographic growth, with an increase from 60,000 inhabitants in 1886 to 100,000 in 1939.10 The city was nevertheless not influential nationally, for in 1911 it was only the 25th largest city in France in terms of population.11 In the nineteenth century, Dijon concentrated the vast majority of petroleum flows and depots in the Côte-d’Or, and it was not until the interwar period that diffusion toward the countryside occurred. The Côte-d’Or was not an automobile centre: the consumption of petrol there was limited, slightly above the national average. While each local case is distinct, the Côte-d’Or offers an interesting field of exploration because it embodies a departmental model that was fairly common in France, namely an administrative city serving as a centre for a fairly isolated rural territory.

This study of the first petroleum depots in the Côte-d’Or thus seeks to shed light on a little-explored area in the traditional French historiography. The history of petroleum in France has for a long time been written through a political or economic prism, with a special focus on major companies and international relations. A few research efforts—non-academic ones—have nevertheless highlighted the sale of petroleum in France at the turn of the twentieth century, adopting a technical approach.12 This article is more in keeping with a historiography focusing on social and environmental issues as well as sensibilities—with special emphasis on dangerous, inconvenient, and unhealthy establishments13—but one that has not closely examined petroleum depots.14 A number of studies on the petroleum industry in France have been published recently, but they involve port areas,15 with rural territories being absent from research to my knowledge. Studies on petroleum depots have primarily been American, and while essentially taking an interest in petroleum producing countries, the situation in petroleum consuming countries has increasingly been considered.16 More generally, this essay’s approach from below via the viewpoint of petroleum vendors—the “voiceless within the energy gesture”17—can illuminate the early petrolisation18 of our society by exploring daily practices linked to petroleum, its representations, and its acceptance by the population, tending toward the emergence of a petroleum “civilisation.”19

This study relied primarily on requests to establish these petroleum depots conserved in departmental and municipal archives:20 there were 45 such requests between 1877 and 1918, and another 960 during the interwar period. In order to store and sell petroleum, a request had to be submitted to the prefect specifying the characteristics of the depot, which was classified as a dangerous, inconvenient, and unhealthy establishment.21 In the nineteenth and early twentieth century, the majority of depots were subject to an enquête de commodo et incommodo (a public planning inquiry), in which the administration inspected the premises, and local inhabitants could contest the establishment, but only before its authorization.22 The petition letters from local residents23 included in these files are my primary source for retracing these protests against petroleum. The situation evolved during the interwar period: the simplification of standards for petroleum depots ceased to require an enquête de commodo et incommodo for the majority of such installations. The files are therefore very different depending on the time period. Petroleum depots—infrastructure connected to the “retail petroleumscape”24—are therefore a rich historical object, shedding light on the conditions in which petroleum was sold as well as relations between vendors and consumers, in addition to crystallizing the conflicts that mobilized public authorities. The local press also provides information regarding miscellaneous news items connected to petroleum, helping to construction representations related to this energy source.25

What motivated protests against the sale of petroleum products? To what extent was this sale nevertheless authorized and accepted? This first section will provide portraits of the first lamp oil vendors, whose activity was contested in the late nineteenth century in the Côte-d’Or. The second will explore the upheavals surrounding the sale of petroleum between 1896 and 1918, when it gradually became connected to the automobile sector. The period was also marked by a peak in criticism surrounding the sale of petroleum. Finally, a third section will examine the new order of magnitude that came after the First World War, as the spread of the automobile lead to an explosion in the number of petrol depots, changes in its sale, as well as the appearance of new tensions.

Back to topSelling Lamp Oil in the Late Nineteenth Century (1877-1896)

Grocers, Hardware Stores, and Itinerant Vendors

In the late nineteenth century, lamp oil was sold in businesses specifically dedicated to petroleum products, in addition to grocery stores, hardware stores, drug stores, and even some pharmacies.

While these stores selling petroleum on a retail basis stored small quantities, some larger depots appear in the archives, for they required an enquête de commodo et incommodo. This was the case for the one operated by M. Housse-Petitjean, who moved his oil shop to Dijon in 1887, and added a lamp oil depot to it.26 Like a number of other French oil companies, the merchant diversified his activity, which originally involved vegetable oils.27 The vast majority of these Côte-d’Or petroleum vendors were located in Dijon.

The other points of sale for petroleum in the Côte-d’Or at the time left little trace in administrative sources. However, thanks to advertisements in local newspapers, it is possible to identify the grocery stores that sold lamp oil. For example, the Dijon brand Au Sucre Découpé offered delivery in the city and the nearby countryside.28 It was common for itinerant vendors to use cars or horse-drawn carts.

It was these non-specialized vendors who helped bring petroleum to the inhabitants of the Côte-d’Or. Yet as mentioned earlier, these actors were criticized and associated with fires. In fact, in order to increase their production, some producers were tempted to add essence de pétrole (essence of petroleum) to heavier oils, making them more flammable. The refiner thereby sought to increase profits to the detriment of safety. This addition helped make the oil more fluid and rise higher in the wicks of oil lamps, thereby diffusing more light.29 These explosive blends could also result from errors in distillation, which were certainly quite common in the 1860s, before becoming more rare later on. Protests of this type of incident could not be found in the context of this study, essentially because we do not dispose of sources before 1877, and because requests to install petroleum depots did not concern itinerant vendors.

The First Depots, Fragile and Dangerous

While the consumption of lamp oil clearly rose until the late nineteenth century,30` and the number of petroleum depots in Dijon increased, these establishment—and retailers indirectly—sparked the fears of local inhabitants. The example of M. Focillon’s store in the residential neighbourhood of Dijon is particularly revealing, as it crystallizes highly varying forms of contestation. This planned depot for the retail sale of petroleum was subject to an enquête de commodo et incommodo in 1882, and was described as “a shack made of planks covered with tiles, which can contain over four barrels with a capacity of 150 litres each.”31 Like many other depots of this period, it was small and flimsily built. The installation request submitted by M. Focillon sparked numerous challenges from local inhabitants, who emphasized the structure’s fragility.

Fears of fire and explosion were mentioned in all instances of opposition. For instance, a property owner affirmed that the depot was a “source of fires and other disturbances.”32 These risks multiplied when these petroleum depots were located near other dangerous establishments. M. Focillon’s petroleum barrels were in close proximity to a locksmith workshop’s forge, which was often burning.

What’s more, the presence of a petroleum depot in the vicinity caused harm both economically and to real property. A complaint regarding M. Focillon’s store sheds light on the rising price of insurance for apartments, as well as their loss in value due to the presence of these flammable barrels. However, the depots on the outskirts of Dijon did not cause as much concern, because they were further away from dwellings. Requests to have petroleum depots relocated outside the city reappear regularly in the complaints of local residents.

The final primary characteristic of these first points of sale for petroleum is that they operated illegally. M. Focillon’s operation began before it received legal approval, and was subsequently called out by the homeowner living across from the depot: “a misfortune could occur due to the deplorable and exceedingly brazen arrangements made by the concerned, even before any administrative authorisation.33” The illegal operation of establishments within this category was common in late nineteenth-century France.34 There were various reasons for such undeclared activity: while most retailers pleaded ignorance, some operated their establishment illegally for fear of a refusal, or to avoid tax payments. It was also more difficult for the administration to order a depot closed if it was already operating.35

Despite the sixty complaints filed against M. Focillon’s depot, it received authorization to operate from the prefect, who found “such opposition marked by exaggeration, and based on an erroneous interpretation of the decree.”36 This outcome was representative, for of the 14 installation requests identified between 1877 and 1896 in the Côte-d’Or, none were refused, and only half prompted challenges. Some were nevertheless subject to additional instructions from the prefect, in an effort to better ensure their safety. A planned depot in Châtillon-sur-Seine, a small city in the north of the department, had to replace its initially intended doors, which were made of pine, with doors made of iron; it also had to install exhaust pipes above the roof in order to facilitate the release of bad odours.37

While petroleum vendors helped diffuse this fuel as an affordable source of lighting, others projected an irresponsible and even dangerous image, creating negative representations with respect to petroleum. The first depots sparked the fears of local inhabitants, fears that often went beyond the dangers connected to the handling of lamp oil. Accidents actually seem to have been rare, hence the indulgence of authorities, especially considering there were relatively few of them in residential neighbourhoods. Petrolisation was therefore not particularly slowed. Opposition toward petroleum depots—those “strange neighbours”38—and the resulting conflicts between retailers and local residents, peaked at the turn of the century, when petroleum assumed a new function, namely propelling automobiles.

Back to topA New Fuel for Sale (1896-1918)

Converting to Fuel

The Côte-d’Or became more familiar with the automobile in 1896 following the Paris-Marseille-Paris raced organized by the Automobile Club de France (ACF),39 which crossed through the department and highlighted the reliability of gas-powered vehicles. Despite autophobic movements,40 which were especially virulent in the French countryside, gas-powered automobiles tended to be accepted, especially thanks to the rise of utility vehicles in the early twentieth century. The mobility of doctors, veterinarians, and bakers was facilitated by this new vehicle, helping to open-up certain rural spaces.41 Petrol became an essential resource, and dependence on it was obvious during the shortages of the First World War, when difficulties in supplying these services with petrol caused concern for local authorities.42

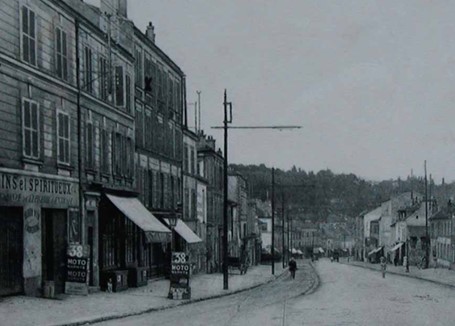

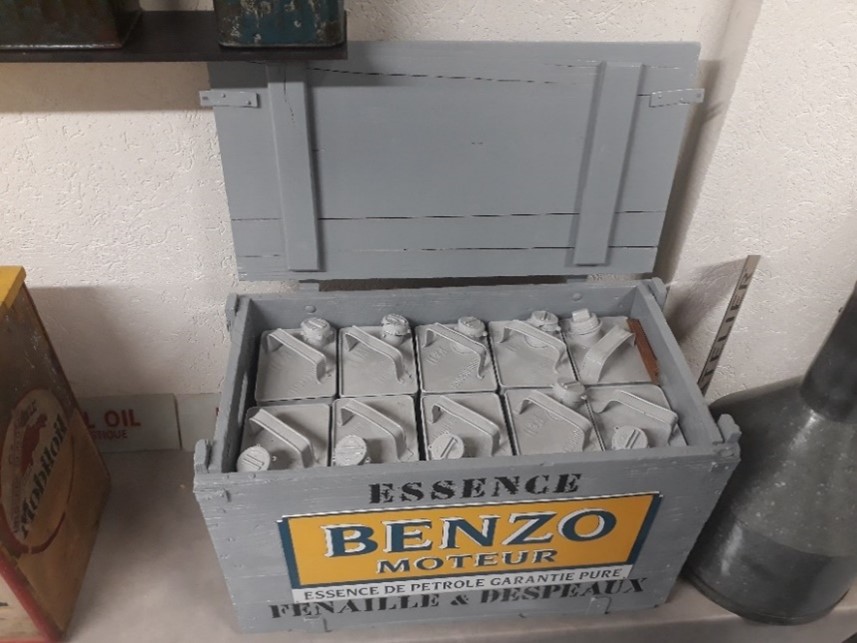

The rise of the automobile and the development of electricity shook up the sale of lamp oil. While oil-based lighting was still common in the early twentieth century, the sale of petrol quickly overtook that of lamp oil, such that the economic interest of the latter decreased for companies. Despite this, the distribution methods for petroleum were not disrupted, as the fuel was initially sold by the same stores offering lamp oil. Since grocers were already clients of oil companies, it was not a difficult transition to make. Furthermore, sale in 5-litre cans—sealed by the state and received in wooden crates painted with the colours and name of the first petrol brands, which had been used by lamp oil vendors since the late nineteenth century—was still the primary form of distribution.43 These crates were often given centre stage in shop windows or on sidewalks in order attract motorists (fig. 2 and 3). However, retailers had to store more cans and barrels in their stores, given that automobiles consumed more petroleum than lamps.

A new category of vendors appeared during the period: bicycle sellers. The automobile was presented as the heir to the bicycle, which had been very much in fashion since the 1880s. Most automobile mechanics had therefore initially specialized in bicycles before converting to automobiles. Within the space of a few years, dozens of automobile mechanic shops, manufacturers, and repair shops appeared in the Côte-d’Or, most of whom also sold petrol. For instance, of the eight manufacturers and repair shops listed in Dijon in 1901, five sold cans of petrol.44 Tour guides such as the Guide Michelin also mentioned these repair shops and points of sale for petrol, thereby contributing to their rise.45

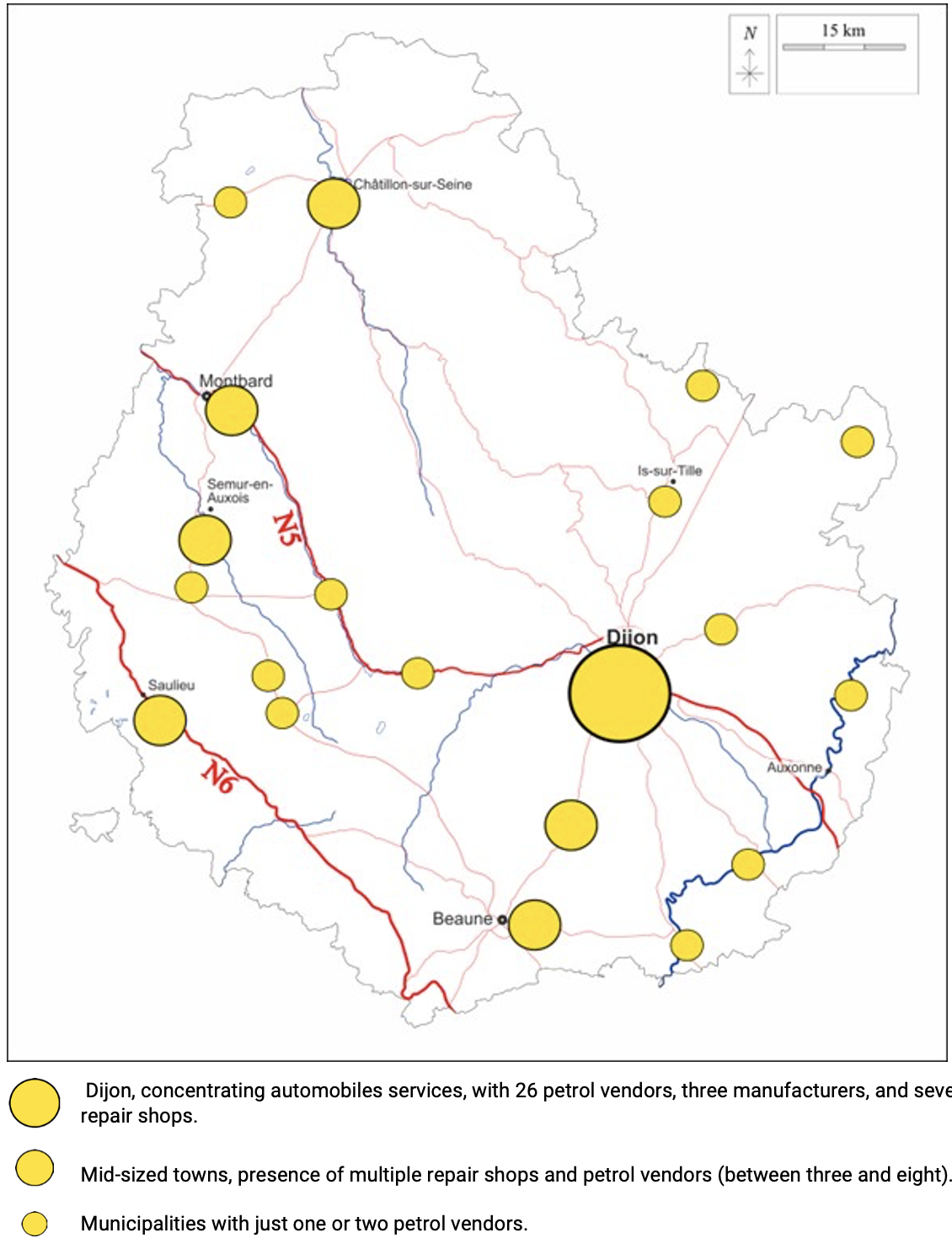

This Annuaire actually enables us to map the petrol depots of the Côte-d’Or in 1901, as well as all automobile professionals. According to this map (fig. 4), 20 towns offered the sale of petrol cans in 1901, with Dijon logically playing the role of the department’s automobile centre. There was a trend of diffusion toward the countryside, but essentially toward secondary cities.

The Sale of Petroleum under Fire

Petroleum depots, which developed in a number of cities in the Côte-d’Or and increasingly assumed more imposing forms, nevertheless raised concerns among local inhabitants, for instance with respect to the contamination of water by petroleum.46 What’s more, olfactory nuisances from inflammable liquid assumed greater importance in complaints compared to the preceding period, with petroleum fumes no longer being described as inconvenient and disagreeable, but as a genuine health risk. One example from 1899 involves plans for a Class 1 petroleum depot in Dijon submitted by M. Vreuille, the agent for the French petroleum company Lille et Bonnières, one of the largest at the time. A petition with 155 signatures asserted that the depot would “poison the neighbourhood with bad odours,”47 revealing a coalition of neighbours opposing the petroleum vendor. The mobilized local residents wrote to the city’s mayor in connection with the enquête de commodo et incommodo, appealing to his compassion: “We would have much to fear for our health, and that of our children.”48

What is distinctive and interesting regarding the file relating to M. Vreuille’s depot is that it contains the vendor’s response to the multiple complaints he received. The enquête de commodo et incommodo highlights the indirect confrontation between the protesting local inhabitants and the vendor. The latter sought especially to dispel fears in order to secure the prefect’s authorisation, and positioned himself as a defender of petrolisation. With regard to the danger caused by petroleum fumes, his answer was quite clear: “Everyone knows that petroleum fumes (if there is any such thing) are rather an antiseptic and purifying agent, which instead of creating danger, destroy all other unhealthy germs present in the vicinity.”49 M. Vreuille thus claimed that petroleum fumes possessed hygienic effects, which was far from being an isolated opinion at the time.50

M. Vreuille opposed the legislative knowledge of nearby industrial actors, who did not protest, with the ignorance of other local residents: “To have them sign, these good people were even made to believe that petroleum was placed directly into wells dug in the ground.”51 He considered that the legal norms and technical equipment in his possession were sufficient to prevent any danger. However, this ignorance should be put into perspective, for even though the origin of petroleum remained vague at the time, there were numerous scientific journals and manuals on unhealthy establishments that allowed the population to inform itself.52 The dangerous and concerning image of petroleum depots was incidentally driven by the press from the beginning of this period, which covered a number of serious accidents both in France and abroad.53

While petitions against petroleum depots could attract hundreds of signatures, their effectiveness was apparently limited.54 M. Vreuille’s depot was authorized in 1899. The power to curb petrolisation was actually in the hands of public authorities: they could require petroleum vendors to adhere to legislation; force them to drastically reduce the volume of petroleum stored; and even issue an unfavourable opinion for a depot. It was at the turn of the century that petroleum operators seeking to install a depot received the most refusals in the Côte-d’Or, with over 10% of requests being refused between 1896 and 1914.55 In addition to the role of the prefect, the mayor of Dijon seems to have had significant influence in the final decision regarding such installations.56 On three occasions he issued an unfavourable opinion for petroleum projects in Dijon due to safety reasons, with the depot being refused all three times by the prefect, who issued the final decree. This was true even when there was wide protest from local residents.57

Other challenges to the sale of petroleum also occurred in the early twentieth century. Local authorities and grocers mobilised against the sale of petroleum on public thoroughfares, but did so for different reasons. For example, in 1906 in Beaune, a city in the south of the department, the city’s Chamber of Commerce took up a petition signed by the city’s grocers against the American company Splendid Light, whose local intermediary operated under the name La Lumière. It sold lamp oil on a retail basis in the street “using tank trailers.”58 Grocers mobilised and complained bitterly about the unfair competition represented by such itinerant trading, which did not adhere to legal obligations, the payment of local taxes in particular. The petition targeted not only Splendid Light, but also the sale of petroleum on public thoroughfares in general. For public authorities, itinerant selling was firstly perceived as “dangerous trafficking,”59 and appears to have been targeted primarily for reasons of control and safety rather than for the defence of local grocers. A petition raised that same year by trade unions for Dijon’s grocers (épicerie) and greengrocers (épiciers-regrattiers) targeted a Dijon petroleum depot—this time a stationary one—also belonging to the La Lumière company. This competition, which was once again denounced by grocers, should be seen in connection with the 1903 law on refining, which weakened small French petroleum companies—and consequently their local intermediaries—and instead allowed the expansion of Anglo-American trusts in France.60 The local administration nevertheless authorized the depot, which it deemed safe and “profitable for the population.”61 Petroleum consumers were favourably disposed to the arrival of Anglo-American companies on the market, which offered better prices. For instance, a counter-petition was issued in Beaune to support a La Lumière depot against grocers.62 Here the process of petrolisation was torn between two logics. On the one hand were grocers, the traditional vendors of lamp oil, who were threatened by Anglo-American competition, and sought to maintain local control over the sale of petroleum. On the other were consumers, who were favourable toward affordable petroleum, and had the support of public authorities as long as such sales were safe. It was ultimately through the issue of safety, enhanced by the rise of the petrol pump and the underground tank, that the petrolisation of the Côte-d’Or expanded in scale during the interwar period, revealing a public policy in favour of petroleum depots.

Back to topPetrol Pumps by the Hundred (1918-1939)

Well-Received Petrol Depots

The First World War marked a turning point in the sale of petroleum in France. The strategic interest of fuel, which was requisitioned but largely insufficient in France, grew as the conflict became bogged down. Following the war, the management of this energy had to be reassessed, and the distribution of petroleum on the local level had to change radically. Henry Béranger, an agent at Essences et Combustibles, was quite clear regarding the new strategy to adopt:

“Making the petroleum issue into a private grocer issue is truly no longer possible after the 1914-1918 period. The global revolution born of the war calls for other arrangements after the victory.”63

These arrangements, which were established across all of French territory—and especially from 1922 onwards for the Côte-d’Or—were described by the Minister of Public Works (Travaux Publics) in a circular to the chief inspector of the Côte-d’Or department. Local authorities were invited to “facilitate, as much as possible, all new installations likely to eliminate the handling and storage of petroleum and petrol in cans,” especially “underground stations with petrol pumps,” which present “the least amount of danger and inconvenience for traffic.”64 The petrol pump and the underground tank, technical innovations originally from America, ensured the safety of petroleum depots and facilitated their diffusion. Three types of pumps should be distinguished: mobile systems on rolling carts, with the fuel stored in a barrel; wall-mounted pumps that do not encroach on public thoroughfares; and fixed pumps connected to an underground tank.65

These new techniques were especially introduced among the civilian population of the Côte-d’Or in the spring of 1920, namely in the form of American military equipment that was not repatriated, and instead sold on site.66 On the level of the department, Anglo-American companies such as Standard Oil, Anglo-Persian, and Royal Dutch/Shell promoted the diffusion of these new techniques beginning in 1922, all the way through the small villages of the Côte-d’Or.67 As pumps were costly, most of those used by retailers belonged to these major oil companies.68 For example Standard Oil, operating in France via its subsidiaries such as L’Économique and La Compagnie Générale des Pétroles, provided Gilbert & Barker pumps to their associated petrol vendors (fig. 5). The same practices can be observed for other French companies, such as Desmarais Frères. It was incidentally these companies that generally completed the administrative procedures required to install petrol depots, for instance by drawing up the designs for the establishment, and provided retailers with instructions on the functioning of the pump, thereby increasing their control over the distribution of petrol. Aside from greater precision and less danger, these pumps also had the advantage of being highly visible to motorists, and were thus profitable for vendors. They contributed to a uniformisation of the image of oil companies,69 petrolising the Côte-d’Or landscape. The state also sought to oversee these new techniques, and very quickly regulated their use: only pumps stamped with a numbered registration plate were authorized to be in service.70

In the Côte-d’Or, local authorities followed ministerial instructions, and authorized new petroleum projects on a massive scale, especially if they included these underground tanks and petrol pumps. Aside from a few refusals and reservations expressed between 1919 and 1921 for depots that did not include these technical features, it became very rare for the Côte-d’Or prefect to refuse the installation of a petrol depot. Between 1922 and 1939, there were only four rejections among 960 applications. These numbers should be seen in light of the fact that almost all petroleum depots fell under Class 3 of dangerous, inconvenient, and unhealthy establishments pursuant to the decree of 24 December 1919, which changed the classification, and unlike the preceding period no longer required an enquête de commodo et incommodo for Class 3 depots.71 Even when protests by local residents were allowed, for Class 1 establishments, authorities tended to reduce them to silence, especially in rural areas, where it was easy to elude weak opposition to certain projects. The role of mayors in the final decision appears to have decreased. It is in this context that the sale of petroleum in the Côte-d’Or should be viewed, with the primary consideration being responding to the requests of motorists.

Petrol Vendors on the Road to Motorists

Utility vehicles continued to develop, and the rise of tourism also had an effect on the sale of petroleum in the Côte-d’Or during the interwar period, with the department being at the heart of numerous touristic routes connecting Paris to Geneva and the Mediterranean.72 As the number of automobiles increased,73 petrol consumption rose sharply in France: imports grew from 1.5 M/t in 1920 to 3.1 M/t in 1926 and 4 M/t in 1930.74 As a result, a wide range of infrastructure, such as petrol depots, emerged in response to the needs of motorists. In the space of 20 years, the department became dotted with supply stations (fig. 6). These depots were concentrated in cities, but they were highly present in rural areas as well.75

Other types of petrol vendors appeared during the interwar period, diversifying this activity even further. Numerous cafés and inns in small rural municipalities equipped themselves with one or two petrol tanks, rarely larger than 5,000 litres, to supply motorists stopping over, thereby securing a little bit of additional income (fig. 7). In addition, the Côte-d’Or saw an expansion of local branches during the interwar period, with establishments such as Économiques bisontins or Comptoirs de la Bourgogne increasing their number of local stores, which were equipped with petrol pumps. For instance, Comptoirs de la Bourgogne had petrol pumps in eight municipalities in the Côte-d’Or.76 The number of mechanic shops also grew during the interwar period. There were numerous repair shops that had one or two petrol pumps. These garages were primarily located in areas with higher concentrations of motorists: in Dijon they were located in the east and near the city centre, neighbourhoods with a bourgeois population.77

Specialisation in the sale of petrol nevertheless took hold in very tentative fashion. The terms “station d’essence” (petrol station) and “station de remplissage” (filling station) appeared in the early 1920s, with station-service (service station) coming much later. In 1925, La Revue Pétrolifère addressed this subject, emphasizing France’s lag in the retail sale of petrol compared to Anglo-American countries.78 The pace of petrolisation varied greatly depending on the territory, with the journal emphasizing that stations with extravagant architecture inspired by American establishments emerged in the South of France.79 Some stations in the Côte-d’Or seem to have approached this model during the 1930s, such as the Modern Station located in a Dijon suburb in 1935, which had an awning over a concrete paved area equipped with four pumps.80 This configuration, which is common today, was innovative and rare in the Côte-d’Or at the time. The term “station-service” appeared for the first time only in 1932 in an advertisement in the local press,81 before the arrival of service stations, albeit exclusively in Dijon.

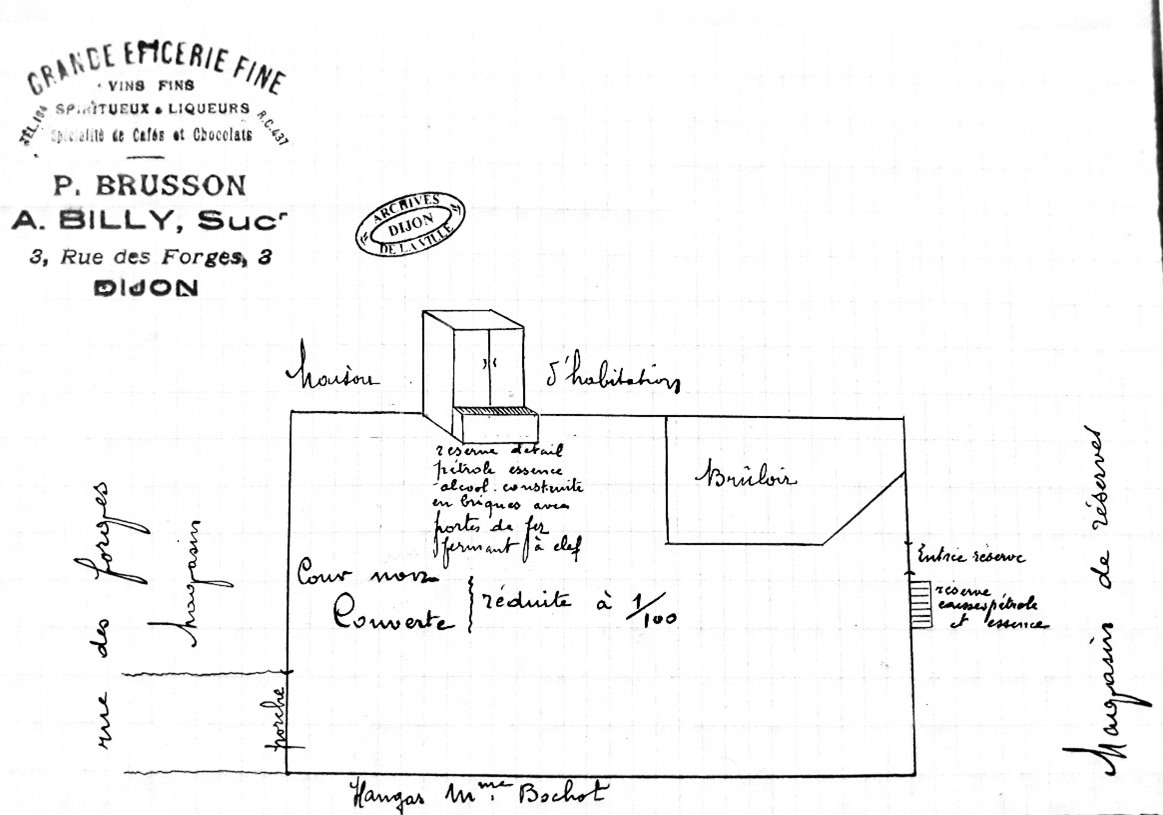

Traditional vending nevertheless persisted. Grocers and hardware stores still controlled a significant portion of distribution. While petrol pumps gradually replaced crates of petrol cans in front of their stores, traditional distribution methods were still common. In 1928, 40% of retailers in France still sold petrol in cans82; the grocer M. Billy in Dijon stored his petrol in an iron cabinet (fig. 8).

Competition and Precariousness

This proliferation of petrol sites during the interwar period also resulted in fierce local competition between oil companies. French companies and subsidiaries of Anglo-American companies sought to take over streets and villages, and to attract the most motorists. They distinguished themselves through their name, pump colour, and pricing for petrol. This competition led to fairly farcical situations. Take for example the rue du Drapeau in Dijon. Five petrol depots appeared in just this street between 1924 and 1926, each with a petrol pump supplied by underground tanks, with a capacity varying between 1,200 and 4,000 litres. Between 1929 and 1931, five additional points of sale were installed. While the sources do not identify all of the suppliers for these retailers, at lease three oil companies were competing over this street: Desmarais Frères83; the Société Générale des Huiles de Pétrole, a representative of Anglo-Persian84; and La Pétroléenne, which was connected to Standard Oil.85 This example, which is far from an isolated one in Dijon, shows the proliferation of petrol depots in some neighbourhoods, and was also true of certain rural municipalities.

However, this overconcentration led to precariousness for some petrol vendors. With 40,000 to 50,000 points of sale in France in 1928, there was one petrol site for every 20 motorists.86 Consequently, very few retailers survived just on petrol distribution, which slowed the specialisation of this activity, and sparked tensions between competing vendors. In addition to the economic crisis of the early 1930s, the most modest vendors were weakened by the political and economic context related to petroleum. The French government did not want to repeat the error of the First World War, when it was dependent on the United States. It was under these conditions, for instance, that the Compagnie Française des Pétroles was created in 1924, one of whose objectives was to exert greater control over petroleum distribution in the face of Anglo-American trusts.87 The effectiveness of this policy was nevertheless limited, as trusts tended to brutally monopolize the French market by lowering the sale price of petrol or by offering discounts to their local intermediaries, thereby weakening the petrol vendors not associated with them.88

This context caused great disparities in sale price among vendors, as well as in terms of area. “This competition was naturally the fiercest at points of high consumption,” and “much lower in small centres and rural areas.”89 The sale price for petrol in the Côte-d’Or was largely above the national average because the “guerre des prix” (price war) was less intense there, although competition could be stiff in certain cities. For example, in 1931 a can of petrol cost 7.50 francs in Paris and 11 francs in the Côte-d’Or.90 Motorists in the Côte-d’Or, who were disadvantaged by this political and economic context, mobilised against what they saw as an injustice. An opinion column published by a Dijon motorist in Le Progrès de la Côte-d’Or in 1932 explicitly accused the consortium of Anglo-American companies of manipulating prices. Two problems were emphasized: “large importers” from America absorbed “small ones,” thereby extending their monopoly; and motorists in the provinces were indirect victims of this “guerre des prix” (price war), which on the contrary favoured Paris.91 This voice was far from being an isolated one, with the mayor of Dijon himself complaining about this to the minister of Commerce in 1931.92 While they were late in coming, a few responses by the state emerged, such as a decree-law was implemented in August 1935,93 requiring prefects to monitor the sale price for fuels in the department, and establishing price limits.94

Faced with the many excesses connected to the sale of petrol, the state sought to control a petrolisation that was actually dictated by Anglo-American companies. Tensions with local resident were dismissed, and it was motorists who voiced the sharpest criticism of the system used to sell petroleum, especially in the provinces.

Back to topConclusion

This article ultimately provides only an overview of the sale of petrol in the provinces at the turn of the twentieth century.95 Despite the relevance of the Côte-d’Or context, a comparative study with more rural or urbanized provincial areas would allow for a broader analysis of the early sale of petrol. It is also important to keep the overall context in mind, with the retail petroleumscape being only one element within the global petroleumscape.96 This study could also be expanded by analysing the sources of oil companies, which would provide a more detailed picture of relations between retailers and importers.97 A study of advertising posters would also further explore the issue of representations relating to petrol.98

By studying the sale of petrol in the provinces between 1877 and 1939, this study ultimately sought to shed light on this little-known aspect in the historiography, which has not taken sufficient interest in such territories or in this period. It also showed that petrolisation was a contested and irregular process, one that was supported or denounced by local actors depending on their interests. Residents living near depots were the first to fight petroleum, fearing for their comfort and health. Moreover, the penetration of trusts within the Côte-d’Or in the early twentieth century and the interwar period paradoxically accelerated and weakened petrolisation: technical contributions and lower prices for petroleum should be weighed against vendors facing competition and disadvantaged provincial motorists. With regard to public authorities, they appear to have been powerless in the face of this petrolisation, which was actually in the hands of trusts. Initially ambivalent, authorities in the end defended petrolisation, with petrol “henceforth [being] as widespread as essential food products.”99

In 1939, 90,000 petrol pumps and 1,050 depots (with a capacity of 20,000 litres or more) supplied France’s 2.3 million automobiles and 500,000 motorcycles.100 The Second World War nevertheless marked a sudden rupture. Petrol depots were destroyed, and vehicles and fuel were requisitioned by the occupier; petrol pumps disappeared from the landscape, and shortages took hold across France. The vast majority of petroleum vendors stopped their activity.101 The war nevertheless drove the process of petrolisation, and the post-war period established the conditions for a change in scale.

- 1. Albert Dupaigne, Le pétrole. Son histoire, sa nature, ses usages et ses dangers (Paris: Victor Palmé, 1872), 6.

- 2. Alain Beltran and Pascal Griset, Histoire des techniques aux XIXe et XXe siècles (Paris: Colin, 1990), 230.

- 3. Mathieu Auzanneau, Or noir. La grande histoire du pétrole (Paris: La Découverte, 2015), 21.

- 4. At the time this was essentially the United States and Russia, although new deposits were discovered in the early twentieth century in Romania and Latin America.

- 5. Serge Jamais, “Implantation des raffineries pétrolières”, (Ph.D. diss., Université de Bourgogne, 1967), 38.

- 6. François Galliot, “Les voies de communication de la Côte-d’Or”, in Dijon et la Côte-d’Or en 1911 (Dijon: 40e Congrès de l’Association pour l’avancement des sciences, 1911).

- 7. Pierre Gras (dir.), Histoire de Dijon (Toulouse: Privat, 1981), 301.

- 8. In 1891, industry in Dijon provided 10,000 jobs. See Robert Chapuis, “Dijon, ville industrielle ? ”, in Jean-Michel Cadet et al, “Dijon et son agglomération”, Notes et Études documentaires, n° 4862, 1988, 69-81.

- 9. Jules Guicherd, “Notes de démographie départementale : population ; natalité ; nuptialité ; mortalité”, in Dijon et la Côte-d’Or en 1911, 279-288 (cf. note 6).

- 10. Jean-Bernard Charrier, “Dijon au XIXe siècle et dans la première moitié du XXe”, in Cadet et al, “Dijon et son agglomération”, 18-21 (cf. note 8).

- 11. Michel Huber, “Le recensement de la population française en 1911”, Journal de la société statistique de Paris, tome 53, 1912, 141-148.

- 12. Christian Rouxel, “Bref historique de la vente d’essence en France”, Route Nostalgie, n° 5, 2004 and Serge Miraucourt, “Histoire de la pompe à essence”, Culture technique, n° 9, 1983.

- 13. A non-exhaustive list includes Alain Corbin, Le miasme et la jonquille (Paris: Champs Flammarion, 2016 [1982]) ; Geneviève Massard-Guilbaud, Histoire de la pollution industrielle en France, 1789-1914 (Paris: EHESS, 2010) ; Michel Lette and Thomas Le Roux (dir.), Débordements industriels. Environnement, territoire et conflit (XVIIIe-XXIe siècle) (Rennes: PUR, 2013).

- 14. For instance, Geneviève Massard-Guilbaud cites a case involving the explosion of a petroleum depot in Nantes in 1903: Massard-Guilbaud, Histoire de la pollution industrielle en France, 154, (cf. note 13).

- 15. For the petroleum industry in ports in Normandy and the Seine Valley, see Morgan Le Dez, Pétrole en Seine (1861-1940). Du négoce transatlantique au cœur du raffinage français (Bruxelles: PIE Peter Lang, 2012). On the legacy of petroleum infrastructure in Dunkirk, see Carola Hein, Christine Stroobandt and Stephan Hauser, “Petroleumscape as Heritage. The Case of the Dunkirk Port City Region”, in Carola Hein (dir.), Oil Spaces: Exploring the Global Petroleumscape (New York: Routledge, 2021), 263-280.

- 16. For example, Carola Hein has developed the concept of a “global petroleumscape”—the global and interconnected petroleum landscape—within its spatial, material, and cultural dimensions. The concept also emphasizes the role of petroleum actors in shaping this petroleumscape on various scales: Hein (dir.), Oil Spaces, 7-14 (cf. note 15).

- 17. Gwenola Le Naour and Vincent Porhel, “Documenter les impacts sanitaires et environnementaux des activités pétrolières : un enjeu pour les sciences participatives”, Natures Sciences Sociétés, vol. 29, n° 3, 2021, 342. Some research has nevertheless studied these petroleum vendors, on a larger scale and for a later period: Elisabetta Bini, “Selling Gasoline with a Smile: Gas Station Attendants between the United States, Italy, and the Third World, 1945–1970”, International Labor and Working-Class History, n° 81, 2012, 69 93.

- 18. To our knowledge, the term petrolisation is essentially used to denote a process ascribing petroleum an increasing role as an energy source and raw material for an ever-increasing number of objects. Some research has emphasized this petrolisation in France, but chiefly focusing on later periods and/or various petroleum activities. See Renaud Bécot, Gwenola Le Naour and Stéphane Frioux, “Inflammation du verbe moderniser : Feyzin 1966, une catastrophe dans le tournant pétrolier de l’économie française”, in Stéphane Frioux (dir.), Une France en transition : urbanisation, risques environnementaux et horizon écologique dans le second XXe siècle (Paris: Champ Vallon, 2021), 125 153, here 152 ; and on petrochemistry, see Le Naour and Porhel, “Documenter les impacts sanitaires…” (see note 17).

- 19. Charles-François Mathis, La Civilisation du charbon. En Angleterre, du règne de Victoria à la Seconde Guerre mondiale (Paris: Vendémiaire, 2021).

- 20. Our sources consisted mostly of various file series: at the Archives départementales de Côte-d’Or (ADCO), call numbers SM 16887 to 16925 for files relating to dangerous, inconvenient, and unhealthy establishments; at the Archives municipales de Dijon (AMD), files number 595 to 841 from series 5 I 3 relating to petroleum depots.

- 21. In connection with the decree of 1810, which divided harmful establishments into three categories. The decree of 19 and 24 May 1873 provided additional details for this classification of petroleum depots, with the following rule: the greater the volume stored, the more the establishment was considered dangerous, and hence subject to health and safety standards.

- 22. Studies have broadly shown the industrialist aim of such decrees, but these enquêtes de commodo et incommodo reveal the voices of local inhabitants. See Corbin, Le miasme et la jonquille, 153 (cf. note 13).

- 23. The actors opposing these dangerous, inconvenient, and unhelathy establishments, including local residents, have been the subject of a great deal of research, which has emphasized their social background or modes of action: François Jarrige and Thomas Le Roux, La contamination du monde. Une histoire des pollutions à l’âge industriel (Paris: Seuil, 2017), 159-166

- 24. Hein, Oil Spaces, 10 (cf. note 15).

- 25. Le Progrès de la Côte-d’Or was consulted in a comprehensive manner, along with a few articles from Bien Public, Rappel des Travailleurs, and the specialized journal La revue pétrolifère.

- 26. AMD 5 I 3 n° 602, 1887, dossier relatif au dépôt de M. Housse-Petitjean (file relating to the depot of M. Housse-Petitjean).

- 27. Rouxel, “Bref historique...” (cf. note 12).

- 28. Le Rappel des travailleurs, 4 October 1896.

- 29. Duapigne, Le pétrole, 53 (cf. note 1).

- 30. Average consumption of lamp oil per inhabitant was 1.6 kg in 1878 and 4.8 kg in 1889, with the rise continuing at least until 1894: Louis Galine, Traité général d’éclairage. Huile, pétrole, gaz, électricité (Paris: Editions Bernard et Cie, 1894), 394.

- 31. AMD, 5 I 3 n° 596, 1883, dossier relatif au dépôt de M. Focillon (file relating to M. Focillon’s depot).

- 32. Id.

- 33. Id.

- 34. Massard-Guilbaud, Histoire de la pollution industrielle en France, 118-119 (cf. note 13).

- 35. Estelle Baret-Bourgoin, “Modifications du paysage industriel et esprit industrialiste : les autorités municipales face aux pollutions industrielles à Grenoble au XIXe siècle”, in Christoph Bernhardt and Geneviève Massard-Guilbaud (dir.), Le Démon moderne. La pollution dans les sociétés urbaines et industrielles en Europe (Clermont-Ferrand: Presses universitaires Blaise-Pascal, 2002), 307.

- 36. AMD, 5 I 3 n° 596 (cf. note 31).

- 37. ADCO, SM 16888, 1888, arrêté préfectoral concernant le dépôt de la Société Deutsch et Cie (prefectoral order relating to the depot of Deutsch et Cie).

- 38. Judith Rainhorn and Didier Terrier, Étranges voisins. Altérité et relations de proximité dans la ville depuis le XVIIIe siècle (Rennes: PUR, 2010).

- 39. On the social and cultural history of the automobile, see Clay McShane, Down the Asphalt Path. The Automobile and the American City (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995); Mathieu Flonneau, Les cultures du volant : essai sur les mondes de l’automobilisme : XXe-XXIe siècles (Paris: Autrement, 2008); Gijs Mom, Atlantic Automobilism. Emergence and persistence of the car, 1895 – 1940 (New York/Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2015).

- 40. See especially Patrick Fridenson, “La société française face aux accidents de la route (1890-1914)”, Ethnologie française, t. 21, n°3, juillet-septembre 1991, 306-313.

- 41. For further details, see for example Etienne Faugier, “L’économie de la vitesse : l’automobilisme et ses enjeux dans le département du Rhône et la région du Québec (1919-1961)” (Ph.D. diss., Université Laval, 2013), 386-424.

- 42. ADCO, SM 9799, lettre du préfet de la Côte-d’Or au ministre de l’Agriculture et du Ravitaillement en date du 20 février 1917 (letter from the prefect for the Côte-d’Or to the Minister of Agriculture and Provisions dated 20 February 1917).

- 43. Rouxel, “Bref historique...” (cf. note 12).

- 44. Annuaire général de l’automobile et des industries qui s’y rattachent (Paris: F. Thévin & Ch. Houry, 1901), 253-254.

- 45. Pierre Lidoine, Cottereau et d’autres rendez-vous de Dijon avec l’automobile (Besançon: Besançon Autos Miniatures, 2007), 7.

- 46. AMD, 5 I 3 n° 612, 1899, dossier relatif au dépôt de M. Vreuille, procès-verbal de l’enquête de commodo et incommodo (file relating to depot of M. Vreuille, summary report from the enquête de commodo et incommodo).

- 47. Ibid., pétition adressée au maire de Dijon (petition addressed to the mayor of Dijon).

- 48. Ibid., (cf. note 46).

- 49. Ibid., lettre de M. Vreuille au maire de Dijon (letter from M. Vreuille to the mayor of Dijon).

- 50. Corbin, Le miasme et la jonquille (cf. note 13) ; Massard-Guilbaud, Histoire de la pollution industrielle en France, 70-72 (cf. note 13).

- 51. AMD, 5 I 3 n° 612 (cf. note 46).

- 52. Massard-Guilbaud, Histoire de la pollution industrielle en France, 217-218 et 222-223 (cf. note 13).

- 53. For example, in Anvers in 1889, a fire caused by petroleum that resulted in 125 casualties was reported on by Le Progrès de la Côte-d’Or. On the role of the press see Stéphane Frioux, Les batailles de l’hygiène. Villes et environnement de Pasteur aux Trente Glorieuses (Paris: PUF, 2013), 167-169.

- 54. Unlike other requests for dangerous, inconvenient, and unhealthy establishments, it appears that writing was the only mode of action used by residents living near petroleum depots in the Côte-d’Or: Jarrige and Le Roux, La contamination du monde, 159-166 (cf. note 23).

- 55. No requests were submitted between 1914 and 1918.

- 56. On the role of mayors in “hygiene battles” see Frioux, Les batailles de l’hygiène, 84-117 (cf. note 53). For a more general context, see also Baret-Bourgoin, “Modifications du paysage...” (cf. note 35).

- 57. This could potentially be due to the growing importance of the issue of hygiene in Dijon, with the creation of a bureau d’hygiène (hygiene office) in 1901: George Zipfel, “L’hygiène à Dijon”, in Dijon et la Côte-d’Or en 1911 (cf. note 6). The effectiveness of such a body should nevertheless be put into perspective: Lucie Paquy, “La gestion des nuisances et des pollutions grenobloises à la fin du XIXe siècle : institutions et acteurs (1870-1914)”, in Bernhardt et Massard-Guilbaud (dir.), Le Démon moderne, 99 (cf. note 35).

- 58. Archives Municipales de Beaune, 2 EP 57, 1906, rapport de la Chambre du commerce de Beaune sur le dépôt de pétrole dans les gares de chemin de fer et vente sur voie publique (report by the Beaune Chamber of Commerce regarding petroleum depots in railroad stations and sale on public thoroughfares).

- 59. Id. For example, itinerant trading was already prohibited in Bourges and Caen.

- 60. For more details see Marcel Amphoux, “Une nouvelle industrie française : le raffinage du pétrole”, Annales de Géographie, t. 44, n° 251, 1935, 510.

- 61. AMD, 5 I 3 n° 618, 1906, dossier relatif au dépôt de la société La Lumière (file relating to the depot operated by the company La Lumière).

- 62. Le Progrès de la Côte-d’Or, 26 March 1908. No further details regarding this petition could be located.

- 63. Henry Bérenger, Le pétrole et la France (Paris: Plon, 1920), 291, cited by Roberto Nayberg, “La politique française du pétrole à l’issue de la Première Guerre Mondiale : perspectives et solutions”, Guerres mondiales et conflits contemporains, n° 224, 2006.

- 64. ADCO, SM 16898, 1920, lettre du ministre des Travaux Publics à l’inspecteur en chef du département (letter from the Minister of Public Works to the chief inspector of the department).

- 65. Fernand Beaucour, Les Appareils distributeurs de carburants, les stations-services et les voies publiques (Paris: Chez l’auteur, 1956), 32-33.

- 66. Auction sales were held at Camp Williams in Is-sur-Tille, north of Dijon, which was built in 1917. See A. Content, “La gare régulatrice d’Is-sur-Tille”, Mémoires de l’Académie des sciences, arts et belles-lettres de Dijon, t. 100, 1927-1931, 43-51.

- 67. On the diffusion of health-related innovations and technologies in small provincial towns beyond the context of petroleum, see Frioux, Les batailles de l’hygiène, 208-239 (cf. note 53).

- 68. Dominique Pascal, Stations-service (Boulogne-Billancourt: ETAI, 1999), 20.

- 69. This idea was taken up by Jakle and Sculle, who developed the concept of “place-product-packaging” within a North American context: John A. Jakle and Keith A. Sculle, The Gas Station in America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994), 18-48.

- 70. For further details, see Miraucourt, “Histoire de la pompe à essence” (cf. note 12).

- 71. While enquêtes were not required for these depots, authorities insisted on them before 1914, especially to compensate for gaps in administrative control.

- 72. The first associations for motorists and tourism unions emerged in the early twentieth century in the Côte-d’Or, but it was not until the interwar period that automobile tourism expanded in scope. See Jean-Christophe Gay and Véronique Mondou, Tourisme & transport, deux siècles d’interactions (Paris: Bréal, 2017), and for the local scale: Martine Chaunay-Bouillot et Michel Pauty (dir.), Dijon et la Côte-d’Or, Un regard de l’Académie des sciences arts et belles-lettres sur le 20e siècle (Dijon: Le Bien Public les dépêches et Académie des sciences arts et belles-lettres de Dijon, 2003), 72.

- 73. There were 107,000 automobile circulating in France in 1913, and 1.7 million in 1931: Dominique Barjot (dir.), Industrialisation et sociétés en Europe occidentale du début des années 1880 à la fin des années 1960, France, Allemagne-RFA, Italie, Royaume-Uni et Benelux (Paris: CDU SEDES, 1997), 239.

- 74. André Nouschi, La France et le pétrole de 1924 à nos jours (Paris: Picard, 2001), 40.

- 75. This trend can be confirmed in the Morbihan and Côtes-du-Nord departments, with petrol depots penetrating into rural and country roads in the 1930s: Patrick Harismendy, “Du caillou au bitume, le passage à la ‘route moderne’ (1900-1936)”, Annales de Bretagne et des pays de l’Ouest, vol. 106, n° 3, 1999, 105-128.

- 76. ADCO SM 16896, 16897 16901, 16903 and 16906 ; AMD, 5 I 3 n° 658 and 661.

- 77. ICOVIL, Dijon et son agglomération. Mutations urbaines de 1800 à nos jours, Tome 1 (1800-1967) (Dijon: Editions Icovil, 2012), 271.

- 78. A number of works have analysed the American service stations that emerged in the early twentieth century: Jakle and Sculle. The Gas Station in America (cf. note 89) ; Richard W. Longstreth, The Drive-In, the Supermarket, and the Transformation of Commercial Space in Los Angeles, 1914-1941 (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2000).

- 79. La Revue pétrolifère, n° 117, 1925, 178.

- 80. ADCO SM 16914, 1935, dossier relatif au dépôt de M. Boyer à Chenôve (file relating to the depot of M. Boyer in Chenôve).

- 81. Le Progrès de la Côte-d’Or, 26 March 1932.

- 82. Rouxel, “Bref historique...” (cf. note 12).

- 83. ADCO SM 16910, 1931, dossier relatif au dépôt de M. Chauffard (file relating to the depot of M. Chauffard).

- 84. AMD 5 I 3 n° 648, 1924, dossier relatif au dépôt de M. Rouvenaz (file relating to the depot of M. Rouvenaz).

- 85. AMD 5 I 3 n° 646, 1924, dossier relatif au dépôt de M. Weigemborg (file relating to the depot of M. Weigemborg).

- 86. Rouxel, “Bref historique...”, 8 (cf. note 12).

- 87. This new organisation in the distribution of petroleum in France was developed through the prism of Desmarais frères, a shareholder in CFP, and a major player in retail selling in France: Mohamed Sassi, La politique pétrolière de la France de 1861 à 1974 : à travers le rôle de la compagnie privée Desmarais Frères (Paris: Éditions SPM, 2018).

- 88. This is referred to as the “guerre des prix” (price war): Nouschi, La France et le pétrole de 1924 à nos jours, 40-43 (cf. note 74).

- 89. ADCO SM 8550, note de la Chambre Nationale du Commerce de l’Automobile adressée au préfet de la Côte-d’Or au sujet de l’application du décret-loi du 8 août 1935 (note from the National Automobile Chamber of Commerce to the prefect of the Côte-d’Or regarding application of the decree-law of 8 August 1935).

- 90. Le Progrès de la Côte-d’Or, 13 January 1932.

- 91. Id.

- 92. Le Progrès de la Côte-d’Or, 14 April 1931.

- 93. ADCO SM 8550 (cf. note 89). On state actions relating to petroleum during this period, see Nouschi, La France et le pétrole de 1924 à nos jours, 37-57 (cf. note 74).

- 94. Price limits only applied to the top end, meaning that petrol could not rise above a certain price, which was beneficial for a department such as the Côte-d’Or. On the other hand, no limits were established on the bottom end, even as trusts tended to lower their prices to win over the market. The effectiveness of the law-decree thus seems to have been limited.

- 95. For more details, see my master’s thesis on which this article is based: Timothée Dhotel, “Naissance d’un torrent noir. Enquête sur les premiers dépôts de pétrole en Côte-d’Or (1877-1939)” (Master’s thesis, Université de Bourgogne, 2021).

- 96. Hein, Oil Spaces (cf. note 15).

- 97. The archives of Desmarais, for instance, are conserved by the company Total: Anne-Thérèse Michel, “Aux sources de l’histoire pétrolière : les fonds d’archives historiques du groupe Total”, Bulletins de l’Institut du Temps Présent, 2004, n° 84, 99-105.

- 98. For instance, a gender-based interpretation of posters would be relevant: Vanina Pinter, L’affiche a-t-elle un genre ? (Wasselone: Éditions deux-cent-cinq, 2022), 16-17.

- 99. La Revue pétrolifère, n° 289, 1928, 1402.

- 100. Rouxel, “Bref historique...” (cf. note 12).

- 101. Camille Molles, La Fin du pétrole. Histoire de la pénurie sous l’Occupation (Paris: Descartes et Cie, 2010).

Amphoux Marcel, « Une nouvelle industrie française : le raffinage du pétrole », Annales de Géographie, t. 44, n° 251, 1935, 509-533.

Amphoux Marcel, Annuaire général de l’automobile et des industries qui s’y rattachent (Paris : F. Thévin & Ch. Houry, 1901).

Auzanneau Mathieu, Or noir. La grande histoire du pétrole (Paris : La Découverte, 2015).

Baret-Bourgoin Estelle, « Modifications du paysage industriel et esprit industrialiste : les autorités municipales face aux pollutions industrielles à Grenoble au XIXe siècle », in Bernhardt Christoph et Massard-Guilbaud Geneviève (dir.), Le Démon moderne. La pollution dans les sociétés urbaines et industrielles en Europe (Clermont-Ferrand : Presses universitaires Blaise-Pascal, 2002).

Beaucour Fernand, Les Appareils distributeurs de carburants, les stations-services et les voies publiques (Paris : Chez l’auteur, 1956).

Bécot Renaud, Le Naour Gwenola et Frioux Stéphane, « Inflammation du verbe moderniser : Feyzin 1966, une catastrophe dans le tournant pétrolier de l’économie française », in Frioux Stéphane (dir.), Une France en transition : urbanisation, risques environnementaux et horizon écologique dans le second XXe siècle (Paris : Champ Vallon, 2021), 125‑153.

Beltran Alain et Griset Pascal, Histoire des techniques aux XIXe et XXe siècles (Paris : Colin, 1990).

Bérenger Henry, Le pétrole et la France (Paris : Plon, 1920).

Bini Elisabetta, « Selling Gasoline with a Smile: Gas Station Attendants between the United States, Italy, and the Third World, 1945–1970 », International Labor and Working-Class History, n° 81, 2012, 69‑93.

Chapuis Robert, « Dijon, ville industrielle ? », in Cadet Jean-Michel et al, « Dijon et son agglomération », Notes et Études documentaires, n° 4862, 1988, 69-81.

Charrier Jean-Bernard, « Dijon au XIXe siècle et dans la première moitié du XXe », in Cadet Jean-Michel et al, « Dijon et son agglomération », Notes et Études documentaires, n° 4862, 1988, 18-21.

Chaunay-Bouillot Martine et Pauty Michel (dir.), Dijon et la Côte-d’Or, Un regard de l’Académie des sciences arts et belles-lettres sur le 20e siècle (Dijon : Le Bien Public les dépêches et Académie des sciences arts et belles-lettres de Dijon, 2003).

Content A., « La gare régulatrice d’Is-sur-Tille », Mémoires de l’Académie des sciences, arts et belles-lettres de Dijon, t. 100, années 1927-1931, 43-51.

Corbin Alain, Le miasme et la jonquille (Paris : Champs Flammarion, 2001).

Dhotel Timothée, « Naissance d’un torrent noir. Enquête sur les premiers dépôts de pétrole en Côte-d’Or (1877-1939) » (Master thesis, Université de Bourgogne, 2021).

Dupaigne Albert, Le pétrole. Son histoire, sa nature, ses usages et ses dangers (Paris : Victor Palmé, 1872).

Faugier Etienne, « L’économie de la vitesse : l’automobilisme et ses enjeux dans le département du Rhône et la région du Québec (1919-1961) » (Ph.D. diss., Université Laval, 2013).

Flonneau Mathieu, Les cultures du volant : essai sur les mondes de l’automobilisme : XXe-XXIe siècles (Paris : Autrement, 2008).

Fridenson Patrick, « La société française face aux accidents de la route (1890-1914) », Ethnologie française, t. 21, n°3, juillet-septembre 1991, 306-313.

Frioux Stéphane, Les batailles de l’hygiène. Villes et environnement de Pasteur aux Trente Glorieuses (Paris : PUF, 2013).

Galliot François, « Les voies de communication de la Côte-d’Or », in Dijon et la Côte-d’Or en 1911 (Dijon : 40e Congrès de l’Association pour l’avancement des sciences, 1911).

Gras Pierre (dir.), Histoire de Dijon (Toulouse : Privat, 1981).

Guicherd Jules, « Notes de démographie départementale : population ; natalité ; nuptialité ; mortalité », in Dijon et la Côte-d’Or en 1911 (Dijon : 40e Congrès de l’Association pour l’avancement des sciences, 1911).

Harismendy Patrick, « Du caillou au bitume, le passage à la ‘route moderne’ (1900-1936) », Annales de Bretagne et des pays de l’Ouest, vol. 106, n° 3, 1999, 105-128.

Hein Carola, Stroobandt Christine et Hauser Stephan, « Petroleumscape as Heritage. The Case of the Dunkirk Port City Region », in Hein Carola (dir.), Oil Spaces: Exploring the Global Petroleumscape (New York : Routledge, 2021), 263-280.

Hein Carola (dir.), Oil Spaces: Exploring the Global Petroleumscape (New York : Routledge, 2021).

Huber Michel, « Le recensement de la population française en 1911 », Journal de la société statistique de Paris, tome 53, 1912, 141-148.

Institut pour une meilleure connaissance de l’histoire urbaine et des villes, Dijon et son agglomération. Mutations urbaines de 1800 à nos jours, Tome 1 (1800-1967) (Dijon : Editions Icovil, 2012).

Jakle John A. et Sculle Keith A., The Gas Station in America (Baltimore : Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994).

Jamais Serge, « Implantation des raffineries pétrolières », (Ph.D. diss., Université de Bourgogne, 1967).

Jarrige François et Le Roux Thomas, La contamination du monde. Une histoire des pollutions à l’âge industriel (Paris : Seuil, 2017).

Juhel Pierre, Histoire du pétrole (Paris : Vuibert, 2011).

Le Dez Morgan, Pétrole en Seine (1861-1940). Du négoce transatlantique au cœur du raffinage français (Bruxelles : PIE Peter Lang, 2012).

Le Naour Gwenola et Porhel Vincent, « Documenter les impacts sanitaires et environnementaux des activités pétrolières : un enjeu pour les sciences participatives », Natures Sciences Sociétés, vol. 29, n° 3, 2021, 341-345.

Lette Michel et Le Roux Thomas (dir.), Débordements industriels. Environnement, territoire et conflit (XVIIIe-XXIe siècle) (Rennes : PUR, 2013).

Lidoine Pierre, Cottereau et d’autres rendez-vous de Dijon avec l’automobile (Besançon : Besançon Autos Miniatures, 2007).

Longstreth Richard W., The Drive-In, the Supermarket, and the Transformation of Commercial Space in Los Angeles, 1914-1941 (Cambridge : MIT Press, 2000).

Mathis Charles-François, La Civilisation du charbon. En Angleterre, du règne de Victoria à la Seconde Guerre mondiale (Paris : Vendémiaire, 2021).

McShane Clay, Down the Asphalt Path. The Automobile and the American City (New York : Columbia University Press, 1995).

Massard-Guilbaud Geneviève, Histoire de la pollution industrielle en France, 1789-1914 (Paris : EHESS, 2010).

Michel Anne-Thérèse, « Aux sources de l’histoire pétrolière : les fonds d’archives historiques du groupe Total », Bulletins de l’Institut du Temps Présent, 2004, n° 84, 99-105.

Miraucourt Serge, « Histoire de la pompe à essence », Culture technique, n° 9, 1983.

Molles Camille, La Fin du pétrole. Histoire de la pénurie sous l’Occupation (Paris : Descartes et Cie, 2010).

Mom Gijs, Atlantic Automobilism. Emergence and persistence of the car, 1895 – 1940 (New York/Oxford : Berghahn Books, 2015).

Nayberg Roberto, « La politique française du pétrole à l’issue de la Première Guerre Mondiale : perspectives et solutions », Guerres mondiales et conflits contemporains, n° 224, 2006.

Nouschi André, La France et le pétrole de 1924 à nos jours (Paris : Picard, 2001).

Paquy Lucie, « La gestion des nuisances et des pollutions grenobloises à la fin du XIXe siècle : institutions et acteurs (1870-1914) », in Bernhardt et Massard-Guilbaud (dir.), Le Démon moderne. La pollution dans les sociétés urbaines et industrielles en Europe (Clermont-Ferrand : Presses universitaires Blaise-Pascal, 2002).

Pascal Dominique, Stations-service (Boulogne-Billancourt : ETAI, 1999).

Pinter Vanina, L’affiche a-t-elle un genre ? (Wasselone : Éditions deux-cent-cinq, 2022).

Rainhorn Judith et Terrier Didier, Étranges voisins. Altérité et relations de proximité dans la ville depuis le XVIIIe siècle (Rennes : PUR, 2010).

Rouxel Christian, « Bref historique de la vente d’essence en France », Route Nostalgie, n° 5, 2004.

Sassi Mohamed, La politique pétrolière de la France de 1861 à 1974 à travers le rôle de la compagnie privée Desmarais Frères (Paris : Éditions SPM, 2018).

Zipfel George, « L’hygiène à Dijon », in Dijon et la Côte-d’Or en 1911 (Dijon : 40e Congrès de l’Association pour l’avancement des sciences, 1911).