What is French about the “French fear of darkness”? The co-production of imagined communities of light and energy

Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research – UFZ

This essay takes expert assumptions about light preferences as a starting point for a historical inquiry into what I call imagined sociotechnical communities of light and energy. My argument is that historical energy supply systems produced these imaginaries and vice versa, shifting the scales at which public lighting was envisioned and darkness was acceptable. While in the 17th C. dark streets were the norm and even the illumination of single streets was publically contested, innovators of the 18th C. imagined gas light and energy on an urban scale. In the 20th C., electric lighting promoted electrification and the electricity supply systems in countries like France allowed experts to think and standardize lighting at a national level. In the 21st C. the expert imaginary of a light-loving French people is challenged by public environmental concern.

Plan de l'article

- Introduction

- Conceptual background: Imagined sociotechnical communities of light and energy

-

European histories: The co-production of light imaginaries and energy

- Premodern imaginaries of honest citizens in candle light and outcasts in dark streets

- Baroque illuminations and contested royal imaginaries

- Industrial and enlightened imaginaries of urban lights, gas and air

- The normalization of artificial lighting and national imaginaries of electrification

- The co-production of French radiance and French light lovers after World War II

- Contesting expert imaginaries of light and energy

- Conclusion and outlook: Enacting imagined communities of light in the 21st C.

Introduction

It is considered common sense among lighting professionals that the demand for lighting varies significantly not only across the globe but also within Europe. For instance, it is a widely held expert opinion that people in the warmer Mediterranean regions prefer bright, cool-white lighting, whereas Scandinavians in the north will insist on warm and comparatively dim illuminations. Others observe that light preferences can even differ between neighboring countries like Germany and France. A renowned French lighting designer even told me, not without provocation, that unlike Germans, “the French fear the dark”.1 Estimates of the energy consumption for lighting, rough data on light points per inhabitant and maximum radiance measures based on satellite pictures support his claim, suggesting that France is indeed more brightly lit than Germany.2

Nevertheless, the idea of a nationwide fear of darkness is somehow peculiar. On the one hand, physiological factors speak against it. As humans we heavily rely on our eyesight, which explains a general preference for lit environments. On the other hand, nationwide preferences do not correspond with the fact that countries like France are not homogeneously lit. Brighter lights are usually found in populated and prosperous urban areas, while remote areas are often the last bastions of darkness. So, where does the idea of a French nation of light lovers come from?

Looking at France, there are no obvious geographical explanations like “Nordic lighting” or “Mediterranean culture”.3 Instead, lighting professionals often point to the socio-technical relationship between brightly illuminated French cities and off-peak nuclear energy. So did the above-mentioned French lighting designer, who linked the alleged French preference for light and German tolerance for darkness to hard infrastructural facts: Germany does not have 58 nuclear power reactors.

This sociotechnical explanation of lighting preferences adds a new dimension to existing arguments that highlight the important role of cultural aspects like nightlife and light uses or geographical physical or physiological dispositions like daytime light intensity and the climate relative to the equator. At the same time, sociotechnical explanations are well-established in the history and social study of science and technology. In particular, the idea of nationwide light preferences in relation to nuclear power makes it hard not to think of Gabrielle Hecht’s seminal work on the nuclear program of post-war France. Her guiding question, “What is French about the French nuclear program?” taken together with the lighting designers’ statement, also inspired the title and question of this article: What is French about the French “fear of darkness”, or more positively formulated, the alleged nationwide love of artificial light? To answer it, I draw on Hecht’s work, which highlights the performative power of national identity politics in shaping technopolitical pathways.4 Exploring this relationship further, I use Sheila Jasanoff’s and Sang-Hyun Kim’s notion of “sociotechnical imaginaries”, which allows me to link expert assumptions about collective lighting preferences to past, present and future infrastructures of light and energy. My thesis is that infrastructures and innovators’ imaginaries are co-produced. More precisely, sociotechnical energy systems define the scale on which demand for and provision of a certain type of artificial light are enacted.

To explore this co-production in the long-term perspective, I draw on historical primary sources and secondary historical accounts of the evolution of outdoor lighting in Europe. To contrast the past with the present, I draw on field observations and expert interviews with municipal light users and lighting professionals, including the above-mentioned interview with a lighting designer in 2012. This ethnographic research covers a period of ten years, starting with my ethnographic Ph.D project on the introduction of LED lighting in Berlin and Lyon to a current transdisciplinary project on light pollution.5

Based on this data I argue that the establishment of national electricity infrastructures in the 20th C. and the imaginary of French lighting preferences were mutually constitutive. The imagined sociotechnical community of French light lovers can thus be understood as both a historical and performative construct that has long been enacted by experts and is now being challenged by a French love of darkness.

Back to topConceptual background: Imagined sociotechnical communities of light and energy

Lighting experts offer different explanations for why lighting preferences differ. One plausible argument is that solar radiation differs geographically and also affects the ways in which people attune to artificial light at night. Others argue that nightlife differs across cultures and so do lighting practices. This argument is supported by sociocultural perspectives. For instance, a famous historical example is Jun'ichiro Tanizaki’s essay “In Praise of Shadow” (1933), which described the clash of Western light and Japanese culture and design.6 The social scientists Mikkel Bille and Tim Flohr Sørensen explored Danish lighting practices, concluding that warm, white lighting contributes substantially to a specific sense of conviviality and coziness called hygge.7 More recently, Bille rejected what “may be described as geographical determinism” arguing that so-called “Nordic lighting” is related to community-oriented lighting practices rather than lines of longitude.8 This brings him closer to sociotechnical, practice-oriented explanations like Elisabeth Shove’s argument that sociotechnical systems, the symbolic and material qualities of lighting products and the actual uses of and preferences for lighting technology co-evolve.9 Bille further argues that lighting practices in Denmark can constitute “atmospheric communities”, which are not necessarily based on “a collective ‘we’, or moral codex, […] but on “a sense of togetherness”.10

The notion of “imagined communities” thereby goes back to Benedict Anderson, who famously outlined that nations do not have to meet in person to form, share and reproduce a sense of belonging.11 The concept is also used to describe national technopolitics and experts’ future-making activities in historical and social studies of science and technology. In particular, Gabrielle Hecht describes how the French nuclear program shaped both the national identity of postwar France and its technological paths:

National-identity discourse constructs a bridge between a mythologized past and a coveted future […]. This process naturalizes change; it makes proposed novelties appear to be logical outgrowths of past achievements.12

Moreover, Ulrike Felt highlights the “continual exercises need[ed] to maintain shared imaginations” and describes how such exercises helped integrate Austrian identities and “technoscientific futures.”13 Sheila Jasanoff’s and Sang-Hyun Kim’s notion of sociotechnical imaginaries captures the co-production of imagined communities and sociotechnical realities in a long-term perspective and with a special focus on country-specific institutional patterns. In their words, sociotechnical imaginaries can be understood as “collectively held, institutionally stabilized, and publicly performed visions of desirable futures, animated by shared understandings of forms of social life and social order attainable through, and supportive of, advances in science and technology.”14 Sociotechnical imaginaries thus link individual and collective visions, pasts, presents and futures, occupy territories and travel in space. They are powerful because they encode visions of what is scientifically and technologically attainable, as well as “how life ought, or ought not, to be lived.”15

Based on this work, I propose the notion of imagined sociotechnical communities to make a conceptual link between lighting professionals’ public statements about their clients’ preferences and past, present and future lighting practices. This co-productionist approach allows me to explore the emergence and performativity of sociotechnical imaginaries—including the idea of a French fear of darkness—as they are publically enacted and evaluated by lighting experts and innovators. My focus is on outdoor lighting, where light installations are planned and operated by experts. Other than in Bille’s cases of “homely atmospheres”, where people light their living rooms in accordance with their preferences, expert outdoor lighting is not always in line with residents’ expectations and demands.16 In public spaces, actual light preferences can be diverse and are thus not identical with lighting professionals’ assumptions and statements about what their clients like and want. Nevertheless, expert imaginaries of collective lighting preferences are crucial as they are likely to materialize in public space—in the form of specific light colors, levels of brightness, uniformity or diversity. Against this background, it seems worthwhile exploring how such expert assumptions about light preferences relate not only to culture and geography, but also to the sociotechnical energy systems that made artificial light imaginable and real.

Back to topEuropean histories: The co-production of light imaginaries and energy

Looking back at the past 500 years, it becomes obvious that lighting preferences are relative. The imagined French love of light thus appears as a historically contingent notion at a specific moment in the European history of light and energy.

Since the introduction of the first dim streetlights, baselines for acceptable levels of light and darkness have shifted considerably. Energy provision thereby plays a significant role for both the enactment and evaluation of adequate lighting. In preindustrial times when darkness was the rule, oil lanterns in the streets of Paris were celebrated as little suns. Around the year 1800, gaslights began to outshine them. But in the 1880s, gaslit streets looked dim by comparison when the first electric arc lights entered the scene. Furthermore, we see that the availability and price of energy used for lighting affected actual and assumed preferences for light and darkness.17

In this situation, imagined communities of light emerged alongside new energy systems. In this narrow sense of co-production, the promise of more and better light was a key argument for energy transitions, while the establishment of new energy systems created demand for the promised light. As I will show, energy system expansion was reflected in the changing scale of the imagined and then actually illuminated communities—and in the receding darkness.

Premodern imaginaries of honest citizens in candle light and outcasts in dark streets

To better understand the profound transformations brought by the 18th and 19th centuries, we need to begin with European nightlife before public lighting entered the scene. In premodern times, darkness was the norm and light an expensive luxury. As a result, the nocturnal experience and use of artificial light was confined to specific, mostly indoor spaces and limited to shorter or longer periods of time, e.g., to the moment when a torch bearer passed or to the duration of a celebration or church service.

The best lit places were churches. In homes and on public streets, lighting was scarce and a luxury as it consumed costly primary energy resources like bees wax, plant oil or whale spermaceti.18 In the absence of lighting, nightlife in medieval Europe was eerie, intimate and even mystical.19 Nighttime, explains Roger A. Ekirch, “embodied a distinct culture, with many of its own customs and rituals.” Nocturnal public spaces were unruly and uncontrolled: Cities closed their gates at nightfall and imposed curfews on their inhabitants. As Ekirch further remarks, “[i]t would be difficult to exaggerate the suspicion and insecurity bred by darkness.”20 Whoever did still go out onto the dark streets at night raised suspicion and risked being mistaken for a hobo, burglar or prostitute. People caught out on the streets without an important or life-saving mission, i.e., anyone except doctors, midwives, garbage collectors, latrine cleaners or mourners of the dead, risked fines or incarceration.

In the Middle Ages, imagined communities of light were thus restricted by precious resources like candles and oil and confined to homes and churches. Honest citizens were well aware that nocturnal activities ought to take place behind closed doors and gates, and they adapted their nightlife to the lack of visibility and orientation but also to curfews, fears and prejudices.

In the face of the negative social connotations of urban darkness it is not surprising that reformers in cities like Paris already began to envision and implement schemes for stationary street lighting in the 16th C. However, these street lighting schemes were doomed to fail as long as they relied on the collaboration of citizens who were asked to illuminate the public space in front of their houses on their own initiative and at their own expense.21

Baroque illuminations and contested royal imaginaries

The nocturnal streets of European cities changed in the 17th C. when absolutist rulers chose to “let there be light.” Paris was thereby exemplary. In 1667 Louis XIV had the first stationary streetlights installed as part of a police reform. Wolfgang Schivelbusch argues that these first candle-lit lanterns were not much more than “orientation lights or position markers,” which by no means dispelled the darkness but instead imposed the king’s rule and order on the citizens of Paris.22 Nevertheless, these first public lights were groundbreaking because they institutionalized the provision of street lighting, candles and oil supplies in the form of a public maintenance service and a public financing scheme. Yet the new “mud and lanterns tax” (taxe des boues et lanterns), “the only significant direct tax on householders in Paris under the Old Regime,” was not well received by Parisians.23

Comparing the case of Paris with other places in Europe, it seems as though the success of these early street-level public light installations depended on the local authorities’ power and their will to establish and finance costly energy supply and maintenance systems. As Craig Koslofsky reports, Frederick William I, the Great Elector of Brandenburg-Prussia, “ordered in 1679 that the residents of Berlin should hang a lantern light outside every third house at dusk each evening from September to May.” When the citizens argued that they could not afford it and failed to comply, he nevertheless installed 1,600 lanterns at their expense. In Leipzig, the absolutist king Augustus II also “followed the general pattern of royal provision of street lighting seen in Paris, Berlin, and Vienna,” with the exception that in the merchant city a “fee collected to enter the city after dark” covered the maintenance costs of the new streetlights.24 However, rulers’ imaginaries did not necessarily resonate with their subjects’ preferences and were far from nationwide. Louis XIV’s imaginary was only enacted in some Parisian streets, whereas France’s second city Marseille did not see the value and benefits of costly lanterns and opposed the royal will to introduce street lighting.25 The Parisians’ incapability to illuminate the streets in front of their houses, the unpopularity of light-related taxation or the actual restoration of darkness through lantern smashing—which was especially popular in France26—can be considered a contestation of the absolutist royal imaginary of light.27 Apparently the benefits of light did not outweigh its costs, the cumbersome task of providing oil and keeping the flame alive.

While the first public street lighting made urban communal nightlife at least imaginable, albeit contested, the “nocturnalization” of baroque court culture, as Koslofsky calls it, made it socially acceptable.28 As the European nobility began to schedule its public activities and festivities later in the evening and at night, the demand for luxurious illuminations and fireworks arose.29 Again, the French roi soleil was a leading figure. In 1688 Louis XIV had his park of Versailles illuminated by 24,000 wax candles, which were luxury goods at the time30 and thus well suited to reflecting “the grandeur of a ruler” and to “bedazzling” his subjects.”31 In his political Mémoires the king describes his aesthetic politics, which aim to seduce his people by pleasure and not by force: “Our subjects are delighted to see that we [the king] love what they love, or what they are most successful in. We thereby hold their hearts and soul.”32 Obviously, the king’s imaginary of a “society of pleasures,” as Kathryn A. Hoffmann describes it, did not match the lived reality of ordinary people who critically observed or even condemned the luxurious nightlife of the nobility. In this sense, it seems too early in this period to speak of a French love of artificial light. In the 17th C., artificial light seems to have been more an absolutist royal imaginary.

Industrial and enlightened imaginaries of urban lights, gas and air

In the 18th C. the contrast between royal imaginaries and the ideals of new urban elites began to erode during the course of industrialization. In this process, the scale of imaginable communities of light and energy developed from the street level and court context to an urban scale. Entrepreneurs, merchants and tradesmen began to engage in the politics of illumination. They echoed the aesthetic politics of baroque court culture, but the communities they had in mind were the populations of growing industrial cities and European metropolises.Lighting played a significant role in this development, which started in England and soon spread to the continent and France.

By 1730, urban elites in northern English cities had already illuminated their streets with oil lanterns.33 Toward the end of the 18th C. the “spirit of coal” provided the means to really illuminate industrial cities34 and coproduced a gentlemanly imaginary of air and light. The new source of energy changed the relationship between lighting demand and energy supply as well as the temporal and spatial patterns of light and darkness. As a by-product of charcoal,35 coal gas was cheap enough to allow the decoupling of lighting practices from the seasons and the lunar calendar so that lighting became more permanent and part of an industrial work regime—first in factories and then in public streets.36 In terms of space, gaslight had upscaling effects as it depended on the establishment of costly infrastructures. The installation of gasworks and mains required large upfront investments that needed to be refinanced so that the average cost per light point was lower when many gas users were connected to the gas grid. The gaslight pioneer Samuel Clegg describes this shift toward the first economies of scale in lighting as follows:

The supplying of light to the street or parish lamps alone can never be undertaken with economy in any district, the most beneficial applications being in those situations where a quantity of light is wanted in a small space. Where the light is required to be more diffused, the profit is less, owing to the greater extent of services and fittings.37

Since lighting was no longer provided by absolutist rulers but by businessmen, technical feasibility and refinancing became decisive factors in the distribution of light and darkness on an urban scale.38 Industrialists set the conditions for the expansion of gaslight, not just in England but also on the European continent, based on English capital and know-how. The Imperial Continental Gas Association (I.C.G.A.), founded in 1824, first held the monopoly on illuminating cities. Following the new rationale of lighting economies of scale, gas mains were only built in areas where private households could afford the installation costs and high monopolized gas prices so that lighting remained the privilege of wealthier and commercial urban districts.39

The urban divide between light and darkness was intensified by the (quite literally) dark sides of industrial production. Deprived areas had no gas and light but were often situated close to urban gasworks, exposing their citizens to the risk of gas explosions as well as the associated environmental burdens. In the poor quarters of European industrial cities, coal particles blackened the air, house facades, and their residents’ lungs. As Jane Brox points out, gasworks contaminated soils with amonia and sulfur, polluted water supplies, and drove the surrounding area into decline. She quotes a contemporary who complained that “[w]hereever a gas-factory […], there is established a centre whence radiates a whole neighbourhood of squalor, poverty and disease.”40

The social inequalities and problems did not escape the attention of enlightened gentlemen and educated urban elites. Already in the early 19th C., a report by French scientists highlighted the “relative influence of gas lighting on public health.” It also criticized the insufficient environmental assessment of gas lighting in Marseille and pointed to the possible contamination of soil and water and potential negative effects on flora, fauna and public health.41

Mark J. Bouman suggests that the new “status- and class-based segregation” generated and popularized a sensibility for the “contrast of areas at once poor and dark with others that were wealthy and bright.”42This “‘darkness and light’ sensibility” also “entered the language of urban reformers.”43 In their gentlemanly imaginaries, demand for more comprehensible illumination schemes was spurred by a mix of liberal, humanist and commercial ideals. Lighting was associated with casting out vice and crime from shady districts, a “competitive urge” to boost and boast about one’s city, and a desire to improve public health and well-being.44 In a similar vein, Chris Otter highlights 19th C. liberal ideals of “air and light,” understood as a reflection of social order, rationalization and urban improvement.45

The reformers’ new concern with the wellbeing of imagined urban communities is also reflected in public regeneration programs and the establishment of public gas utilities. For instance, in the industrial city of Lyon, the first gaslights were introduced in the 1830s in commercial streets. But it was only in 1847, after the city was granted an official monopoly, that the gas network expanded beyond the city center.46 In German cities too, the I.C.G.A. built gas infrastructures and sold expensive gaslight. When the company’s contract for Berlin ended in 1843, the Prussian Ministry established its own gasworks offering its citizens much cheaper gas prices.47

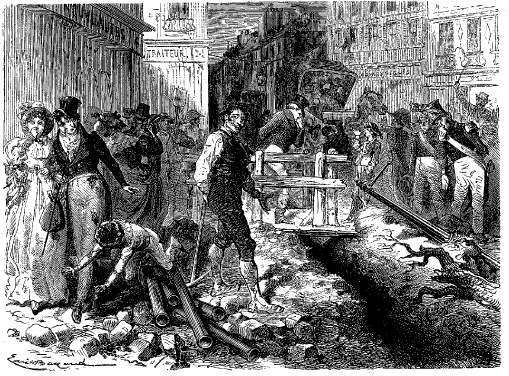

In France, Georges-Eugène Haussmann transformed Paris between 1853 and 1870 with urban designs and infrastructural innovations that are still pertinent today. Appointed by the French emperor Napoleon III, who himself had been inspired by the enlightened urban designs of London, Haussmann gave Paris the image of a ville lumière.48 Wide boulevards replaced dark and narrow streets. The installation of approximately 20,000 public gaslights, where there had only been approximately 9,000 lights before, transformed the city at night. Together with illuminated public buildings, grand magasins and Parisian arcades, gaslights shaped the identity of the French capital, as is documented and represented in the arts and literature.49 Yet there were also less visible but nonetheless profound institutional and infrastructural changes. Under Haussmann’s supervision, the six private gas companies were merged into the Compagnie parisienne d'éclairage et de chauffage par le gaz, with a 50-year license to supply Paris with gas. Moreover, he oversaw the modernization of Paris’s urban infrastructures underground, including the gas mains.

While Paris was an outstanding example, these developments were not unique. As Hernandez Gonzalez points out, an imaginary of social order and commercial display accompanied the introduction of municipal gaslight systems in many French cities.50 Bouman observes that “by the time of Thomas Edison, lights did necessarily come with the modern urban territory.”51

In this sense, the Parisian reformers’ enlightened rational plans and humanist ideals seem more metropolitan than national. Nevertheless, the worldwide appeal of Paris as City of Light in an increasing competition between cities also updated French grandeur and planted the seed of a national imagined community of French éclairagists and light lovers. Electrification provided the basis for national visions and competitions in Europe.

The normalization of artificial lighting and national imaginaries of electrification

In the late 19th C., the co-production of imagined illuminated communities and sociotechnical energy systems entered a new phase and began to develop on a national scale. This process was closely tied to electrification and can be observed in industrialized countries worldwide. It also facilitated the imaginary of a French nation of light lovers as outlined in this section.

With electrification, the world of lighting was transformed. Innovators exploited the lure and convenience of electric lighting to promote the establishment of large technological systems. Light sources diversified, creating an excess of light for the first time. As electricity infrastructures expanded beyond the urban centers, illuminated communities became imaginable on a national scale. Innovators enacted such visions most visibly and in most appealing form in electric illuminations during national festivities and international exhibitions, which allowed lay and expert audiences to celebrate and compare their nations’ technological progress. 52 Although the revolutionary new energy source offered many more advantages than just lighting, enchanting and sublime illuminations seemed the perfect means to publicly display innovation.53 Especially arc lamps exceeded all previous light sources in brightness, and they received great attention in public discourse.54 During the 1881 Exposition International d’Électricité in Paris Thomas A. Edison’s incandescent lamps celebrated their European debut,55 In 1889, the Eiffel Tour was erected and spectacularly illuminated at the occasion of the Exposition Universelle (figure 4). Thanks to such public displays electric lights were able to conquer the world before electricity infrastructures were in place. Indeed, the bright and steady electric light surpassed gaslight not only in terms of light quality but also in terms of cleanliness and the absense of smell. As Beate Binder argues, the sensory advantages of electric light contributed to its victory over well-established gas lighting and incentivized the establishment of urban then regional power stations.56

Sociotechnical imaginaries soon outgrew urban contexts and reached a national scale. The first power stations in Europe were erected in the 1880s in and around cities. While municipalities hesitated to render their gas works obsolete and still discussed whether electric lights should burn on an everyday basis or be reserved for special occasions, innovators and system builders were already imagining and planning electricity supply on a larger scale.The first centralized power stations for regional energy provision were tested in the 1880s. Regional power stations followed around 1900.This infrastructural development “heralded the era of regional electric supply systems, which linked cities, towns, countryside, and remote industrial sites,” writes Thomas Hughes, who also famously showed that this development took place in country-specific ways.57

Country-specific structural differences thereby not only co-produced country-specific sociotechnical systems, but also sociotechnical imaginaries. In Germany for instance, the establishment of rural electric power supply in Germany was not only driven by a vision of modernity and progress, but also by a “social utopia” of countrywide social integration, the ideal of garden cities and tamed urbanization and the reconciliation of city and countryside.58 The provision of lighting played a crucial role in this imaginary.

In France, electrification took place in a more decentralized manner and was linked even more closely to demand for lighting. In the absence of important industrial electricity consumers, electric lighting was the key argument for infrastructural development. Yet, this limited utilization of electricity also hampered the development of electrical power in France.59 As French experts deplored when looking at Germany, la France eclipsed Germany in terms of lighting luxury, but did not aim at “practical applications” like her neighboring country.60

In the course of the 20th C. such enactments of imagined communities of light and electrical energy continued to develop in country-specific ways and also became increasingly nationalist. As Alain Beltran argues country comparisons are “not only a historical exercise,” but were also undertaken by contemporary system builders. “Especially before 1914, Berlin served Parisian representatives as a constant reference point when they considered the growth in electricity use in the City of Light.”61 As electric infrastructures expanded, the city competition developed into a national comparison and competition.62 In the climate of increasing nationalism prior to World War I, electrification and light were increasingly enacted in the form of national imaginaries of modernity and progress.63

With electrification still in full swing, the two world wars had a great impact on both the provision of electric energy and the experience of light. The war-time economies required more energy and led national governments to engage in the establishment of power stations and electricity infrastructures. Yet, these advances did not coincide with more lighting. On the contrary, blackouts were imposed to save energy and hide from the enemy.64 Thus, the wars ended the symbiosis of energy transitions and advancements in lighting. As energy provision became a national task and a prerequisite for industrial development, the relevance of lighting as a driver of energy transitions decreased. The changing relation between light and energy is particularly obvious in post-war France.

The co-production of French radiance and French light lovers after World War II

In the second half of the 20th C., le rayonnement de la France (the radiance of France) was no longer associated with beams of light, but with atoms. As Hecht outlines, this notion of “radiance” differed from aestheticized baroque politics, enlightenment urban renewal and displays of savoir vivre shifting toward realist expert technopolitics.65 Nevertheless, light remained closely connected to energy. Nuclear power provided comparatively cheap energy for illuminating public spaces and buildings, making it easier for light planners to act upon an imagined French fear of darkness/love of light (in Germany, a similar imaginary would have cost twice as much).66

In addition to low electricity rates, the French national energy company EDF, which was a key player in the French nuclear program, also actively contributed to the illumination of France. EDF maintained the streetlights of Paris until 2011.67 In Lyon, the third-largest city in France, EDF contributed to the regeneration of the “black” industrial city into a “City of Light” in the 1990s, supported Lyon’s pionneering role in urban light planning and became a sponsor of the city’s renowned Fête des Lumières (figure 5). 68

Yet what French lighting designers have termed urbanism lumière is not only a Lyonnais speciality, but part of a unique French discourse and urban light planning.69 This French light urbanism challenges allegedly universal technoscientific standards for outdoor lighting that are essentially made for road lighting and car traffic.70 These standards developed in the 1960s as the result of a professionalization and institutionalization of public lighting.

The first national lighting engineering societies in Europe and North America had been founded during the first decades of the 20th C. They became platforms for technoscientific exchange on adequate and “good” lighting and disseminated technical standards.71

Yet the science-based standardization of light outputs and light levels was still not universal. Lighting professionals and national associations developed country-specific ways of lighting. The creation of the European standard for road lighting (EN 13201) is a telling example in this regard. Today, the light-technical parts of the standard are the same in all EU member states, whereas the classification of streets, which defines their respective lighting requirements, was not harmonized and is provided by national standardization agencies like AFNOR in France (NF EN 13201-1). As a result, very similar streets in France, Germany or the UK might fall in different lighting categories with different light levels.

National differences in lighting standards and French light urbanism can both be considered as a French expert approach to lighting, which is also reflected in French lighting institutions. As Bernard Barraqué argues, the French professional society Association Française de l'Éclairage (AFE) was, from its inception, more interdisciplinary and had a greater sense of aesthetics and lighting design, while other illuminating engineering societies in Europe were more technically oriented.72

To conclude, electrification can be regarded as a prerequisite for imagining light preferences on a national scale. In the 20th, the co-production of light and electric energy led to an expansion of light provision not only within cities but also beyond urban agglomerations. The provision of lighting was thereby institutionalized in the form of national standards, professional associations as well as expert imaginaries, which remained, so it seems, widely unchallenged. As experts took over, urban users of public light were less and less engaged in the art and task of lighting. As the marvelling masses of the late 19th C. fell silent and learned to take light for granted in the 20th C., the creative and future-making task of imagining illuminated communities was increasingly left to lighting professionals. In 1984, half of the French citizens who were interogated in a representative survey could not tell whether their municipal lighting experts did a good job or not.73 While experts turned lighting into a science, citizens progressively cared less. This picture also resonates with Michel Callon’s diagnosis of the French nuclear program and “delegative democracy”:

Nuclear power created an undifferentiated public, composed of individuals who were rendered ignorant and entirely deprived of a capacity to participate in decision-making. This public […] became entrenched in French society.74

Thus, the emergence of national electricity infrastructures together with national expert associations and national lighting practices made it possible and plausible for lighting experts to imagine a French preference for well-lit public spaces and a French “fear of darkness”. As long as this expert imaginary remained unchallenged, la France was illuminated accordingly. However, in the 21st C. this situation has changed as the following section shows.

Contesting expert imaginaries of light and energy

Today it seems that established expert assumptions and practices are being challenged by a number of local and global developments.75 At a global level, climate change and the advent of LED technology has profoundly changed the ways in which lighting is envisioned and produced. The LED revolution in lighting has disrupted the primarily nationally organized European lighting markets and produced abstract imaginaries of smart and human-centric lighting. International climate change mitigation policies target lighting as an important area of energy consumption, forcing or incentivizing light users to rethink their demands.76 Meanwhile, electricity costs for French cities and communities have risen considerably as the EU has harmonized its energy markets, giving municipalities even more reason to question their lighting practices.77

But the imagined community of French light lovers is also contested from below. Citizens care about energy-efficient outdoor lighting. In 2012, a public opinion poll showed that almost half of the French population views high light levels as problematic since they consume more energy. More remarkably, the responses suggest that the alleged French love of light is clouded by an emerging concern about the negative ecological effects of artificial light at night (ALAN).78 This fairly new concern is also reflected in a public discourse on light pollution, which does not match the idea of a “delegative democracy”.

Since the 1990s, French citizens have began to mobilize against artificial light at night and promote the preservation of dark skies.79 Led by ANPCEN, the National Association for the Protection of the Nocturnal Sky and Environment, these initiatives culminated in a national law against light pollution.80 While the national scope of the French dark-sky activism appears like an adequate response to the national sociotechnical system of light and energy, it has not developed a national counter-narrative to the imaginary of a French light-loving people. Instead, the national organization ANPCEN mediates and operates on different local and international scales and actively promotes the vision and enactment of local and regional imaginaries of darkness. These new French communities of darkness are not only imagined by experts, but actually enacted by people, e.g. in a national competition for “Star Cities and Villages”—Villes et Villages étoilés (figure 6).

Against this background, the initial provocative statement by a Lyon lighting designer regarding the “French fear of darkness” seems like an expression of a historical configuration. The imaginary of a French nation of light lovers resonates with both a baroque French tradition of luxurious urban light spectacles and illuminated buildings and boulevards, and a national nuclear energy system that guaranteed not only energy safety but also low night-time energy fees. Today there are signs that this nationwide imaginary is losing its performative power and is being replaced by new and emerging imaginaries of local dark-sky communities on the one hand and global smart LED-lit cities on the other.

Back to topConclusion and outlook: Enacting imagined communities of light in the 21st C.

This article took expert assumptions about collective light preferences as a starting point for an inquiry into the emergence of imagined communities of light and energy, as I call them. Looking back at European lighting history and France in particular, I argued that material energy and lighting infrastructures co-produced expert imaginaries of lighting demands. Although these imaginaries did not necessarily reflect actual preferences for light or darkness, they nevertheless shaped the ways the world was lit at night. They also became more powerful in the course of industrialization. As lighting became a professional task, experts’ sociotechnical imaginaries became more consequential. Meanwhile, the comprehension and interpretation of preferences for light and darkness increasingly developed into a domain of professional experience and scientific inquiry. Mikkel Bille critically observes that today “a ‘scientification’ of lighting is taking place, in which the user is a physically responding body more than a social person.”81

Yet the focus on sociotechnical imaginaries also reveals that engineers and scientists operate and develop their ideas in specific sociopolitical contexts. The scientification of lighting did not produce universal demands and norms, but national styles and standards. Moreover, we find that lighting professionals cultivate assumptions about collective preferences that cannot be explained by their photometric experiments and do not necessarily stand up to empirical social-scientific analyses and public opinion polls.82 Instead, the historical overview suggests that expert imaginaries of light are co-produced by energy politics and infrastructures and develop performative power as long as they go unchallenged.

The historical perspective also reveals that imaginaries can change in scale. The upscaling from urban to nationwide imaginaries of light reflected and resonated with the changing scale of energy provision: While in preindustrial times, the high cost of candles and oil lamps made it difficult to imagine the illumination of single streets, the innovators and reformers of the 19th C. imagined and implemented gas and lighting infrastructures on an urban scale. It was only in the 20th C. that electric illumination became imaginable on a national scale. Meanwhile, public lighting had become taken for granted and professionalized, so that the question of individual or collective light preferences and appropriate light levels was no longer a matter of public concern, but inscribed in national lighting standards, debated by national professional communities and supported by national energy supply systems. In this sense, the imaginary of a light-loving French people can be understood as a coproduct of cheap French nuclear energy, a French discourse on national standards and light urbanism and a “delegative” French democracy.83 In the 21st C., this nationwide imagined community of light and energy is being challenged. French energy has become more expensive and less national. The norms and imaginaries of national professional networks are increasingly challenged by global environmental concerns, by European policies and, remarkably for the alleged “delegative democracy”, by civic light pollution protests and initiatives for a darker France.

Thus, the focus on expert imaginaries is also politically relevant. The historical evidence presented here shows that lighting preferences do not have to be scientifically proven to have real consequences.84 Like self-fulfilling prophecies, expert imaginaries have the potential to shape the actual distribution of light and darkness. They thereby reflect and stabilize political economies in highly performative and hence powerful ways. The imagined nationwide preference for light in the 20th C. went hand in hand with national markets for lighting products and services. As such, recent participatory approaches that aim to engage citizens in urban light planning and an increasing body of social-scientific research on the cultural diversity of lighting practices and preferences can offer valuable impulses for rethinking and reimagining communities of light and energy in the 21st C. These reflections are timely and much needed as a response to smart and global LED lighting imaginaries that lack local grounding.

- 1. The conversation took place in Lyon in 2012 during my ethnographic research on the introduction of LED lighting in European cities. See Nona Schulte-Römer, “Innovating in Public” (Ph.D diss., Technische Universität Berlin dx.doi.org/10.14279/depositonce-4908, 2015), 135.

- 2. Ibid. and https://www.lightpollutionmap.info/LP_Stats/?year=2019, last access 2019-05-14.

- 3. Mikkel Bille, Homely Atmospheres and Lighting Technologies in Denmark (London: Bloomsbury, 2019).

- 4. Gabrielle Hecht, “Technology, politics, and national identity in France”, in Michael Thad Allen and Gabrielle Hecht (eds.), Technologies of Power (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001).

- 5. Schulte-Römer, “Innovating in Public” (cf. note 1) and Nona Schulte-Römer, Etta Dannemann, Josiane Meier, Light Pollution – A Global Discussion (Leipzig: UFZ, 2018 - www.lightpollutiondiscussion.net).

- 6. At a time when Tokyo was not yet flooded by the light of media screens, the Japanese writer elaborately describes how the brilliance of Western lighting threatened the aesthetic appeal of Japanese traditional objects and architecture, including lacquerware dishes and toilet designs. Jun'ichiro Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows (Stony Creek, CT: Leete's Island Book, 1977 [1933]).

- 7. “To achieve hygge the amount of light should be sufficient for the members of the social group to see and gain eye contact with each other, while not illuminating the room completely.” Mikkel Bille and Tim Flohr Sørensen, “An Anthropology of Luminosity: The Agency of Light”, Journal of Material Culture, vol. 12, n° 3, 2007, 275.

- 8. Bille, Homely Atmospheres and Lighting Technologies in Denmark, 97-98 (cf. note 3).

- 9. Elisabeth Shove, Comfort, Cleanliness and Convenience: The Social Organization of Normality, (Oxford, UK: Berg, 2003), 57, drawing on Wiebe Bijker, “The Social Construction of Fluorescent Lighting, or How an Artifact Was Invented in Its Diffusion Stage”, in Wiebe Bijker and John Law (eds.), Shaping Technology. Building Society (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992).

- 10. Bille, Homely Atmospheres and Lighting Technologies in Denmark, 99 (cf. note 3).

- 11. Benedict Anderson, Imagined communities (London: Verso, 1983).

- 12. Hecht, “Technology, politics, and national identity in France”, 255 (cf. note 4).

- 13. Ulrike Felt, “Keeping Technologies Out: Sociotechnical Imaginaries and the Formation of Austria's Technopolitical Identity”, in Sheila Jasanoff and Sang-Hyun Kim (eds.), Dreamscapes of Modernity: Sociotechnical Imaginaries and the Fabrication of Power (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 103.

- 14. Sheila Jasanoff and Sang-Hyun Kim (eds.), Dreamscapes of Modernity: Sociotechnical Imaginaries and the Fabrication of Power (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 4, my emphasis. Co-production is defined “as a shorthand for the proposition that the ways in which we know and represent the world (both nature and society) are inseparable from the ways in which we choose to live in it.” Ibid., 3.

- 15. Ibid., 21-23.

- 16. For a worldwide map of lighting conflicts see Schulte-Römer et al., Light Pollution – A Global Discussion (cf. note 6), 185-186.

- 17. Wolfgang Schivelbusch, Disenchanted Night. The Industrialisation of Light in the Nineteenth Century (Oxford: Berg, 1988) and Jane Brox, Brilliant: The Evolution of Artificial Light (Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010).

- 18. Jane Brox also outlines in great detail how whaling in the Atlantic Ocean increased dramatically with the demand for spermaceti candles and whale oil for lighting purposes.

- 19. Roger Ekirch, At Day's Close: Night in Times Past (New York: WW Norton & Company, 2005).

- 20. Ibid., xxv and 8.

- 21. In 1551 a parliamentary decree required the citizens of Paris to illuminate their windows from November to January before six o’clock in the evening. Auguste-Philippe Herlaut, “L’Éclairage des rues à Paris à la fin du 17e et au 18e siècles”, Mémoire de la Société de l’Histoire de Paris et de l’Île de France, vol. XLIII, 1916, 132.

- 22. Schivelbusch, Disenchanted Night, 95 (cf. note 18).

- 23. Herlaut, “L’Éclairage des rues à Paris…”, 140-143 (cf. note 22) and Craig Koslofsky, “Court Culture and Street Lighting in Seventeenth-Century Europe”, Journal of Urban History, vol. 28, n° 6, 2002, 754.

- 24. Ibid., 754-757.

- 25. In Marseille, public lighting was eventually introduced in 1785. Pierre Echinard, “De la lanterne au laser: deux cent trente ans d'éclairage public à Marseille”, unpublished LUCI conference paper (Marseille, 2013).

- 26. Schivelbusch offers an interpretation of the political dimension and consequences (punishment) of lantern smashing, which were particularly severe in France. He concludes that premodern lantern smashing was not just vandalism but a political act of opposition against the absolutist king, and was accordingly severely punished. Wolfgang Schivelbusch, “The Policing of Street Lighting”, Yale French Studies, n° 73, 1987.

- 27. Ibid., 63 and 68.

- 28. “At court and in the cities, nocturnalization is most apparent in the years 1650–1750, when mealtimes, the closing schedules of city gates, the beginning of theatrical performances and balls, and closing times of taverns all moved several hours later.” Craig Koslofsky, “Princes of Darkness: The Night at Court, 1650–1750”, The Journal of Modern History, vol. 79, n° 2, 2007, 236.

- 29. Ibid., see also Alewyn Richard, Sälzle Karl, Das grosse Welttheater: die Epoche der höfischen Feste in Dokument und Deutung (Reinbeck bei Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1959).

- 30. Schivelbusch, Disenchanted Night, 7 (cf. note 18).

- 31. Koslofsky, “Court Culture and Street Lighting in Seventeenth-Century Europe”, 748 (cf. note 24).

- 32. My shortened translation. The French original reads: “Cette société de plaisirs, qui donne aux personnes de la cour une honnête familiarité avec nous, les touche et les charme plus qu’on peut dire. Les peuples, d’un autre côté, se plaisent au spectacle, où au fond on a toujours pour but de leur plaire; et tous nos sujets, en général, sont ravis de voir que nous aimons ce qu’ils aiment, ou à quoi ils réussissent le mieux. Par là nous tenons leur esprit et leur coeur, quelquefois plus fortement peut-être, que par les récompenses et les bienfaits” (The Mémoires of Louis XIV, ed. by Jean Longnon). See Kathryn A. Hoffmann, Society of Pleasures: Interdisciplinary Readings in Pleasure and Power during the Reign of Louis XIV (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1997), 30.

- 33. Jon Stobart links this new “cultured urban life” to a “need for social integration within the growing middling ranks of these towns and their desire to differentiate themselves from ordinary working people.” Jon Stobart, “Culture versus commerce: societies and spaces for elites in eighteenth-century Liverpool”, Journal of Historical Geography, vol. 28, n° 4, 2002, 473.

- 34. Samuel Clegg, A practical treatise on the manufacture and distribution of coal-gas, its introduction and progressive improvement… (London: Weale, 1853).

- 35. For a detailed description see Thomas Cooper, Some Information Concerning Gas Lights (John Conrad & Company J. Maxwell, printer, 1816), 16-17.

- 36. The first gaslit street was Pall Mall in London, which was illuminated as a public display in 1807. It was soon followed by the illumination of more affluent streets in the growing metropolis. Clegg, A practical treatise, 6 and 19 (cf. note 34).

- 37. Ibid., 107. Falkus points out that gaslight was only cost-effective when supply infrastructures could be shared by many consumers. Malcolm E. Falkus, "The Early Development of the British Gas Industry, 1790–1815," The Economic History Review, vol. 35, n°2, 1982.

- 38. In 1813 the English Crown and its Parliament supported the founding of the Westminster Gas-light and Coke Company with a capitalization of £1 million in 80,000 shares. This corresponds to about £9 billion in 2005 prices. The high infrastructural costs became a vehicle for public investment in industrial ventures, adding an economic dimension to the notion of “public” lighting. Charles Bazerman, The Languages of Edison's Light (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999), 149.

- 39. See Klaus Kühnel, Der Pionier des Lichts: Vom Klempnergesellen Zum Großindustriellen ; Die Lebensgeschichte Des Carl Friedrich Julius Pintsch. (Berlin: Trafo, 2015) and Jean-Michel Deleuil, “Du bec de gaz à l'halogène. Les enjeux de l'éclairage public à Lyon”, Bulletin du Centre Pierre Léon d'histoire économique et sociale, vol.1, 1995.

- 40. Brox, Brilliant, 69, and Schivelbusch, Disenchanted Night (cf. note 18).

- 41. The report starts with a description of the status quo, which privileges risk management of accidents over the management of creeping environmental pollution and health risks : “Dès l’année 1817, l’Autorité avait rangé les manufactures des gaz hydrogène pour l’éclairage, dans la 2e classe des établissements insalubres, incommodes ou dangereux. Des mesures sévères avaient été prescrites en vue des dangers d’incendie et d’explosion, les seuls dont on se fut préoccupé d’abord. Quant à l’influence de cette industrie sur la salubrité, elle semble avoir été longtemps négligée…” (Jean-Baptiste-Léonce Malherbe et al., Rapport sur un mémoire de M. Bertulus, de Marseille, relatif à l'influence de l'éclairage au gaz sur la santé publique (Nantes : impr. de Vve C. Mellinet 1855), 1).

- 42. Mark J. Bouman, “Luxury and Control”, Journal of Urban History, vol. 14, n° 1, 1987, 12.

- 43. Bouman gives the example of an “American Progressive” who suggested that “light put a stop to the unsanitary practice of throwing garbage, waste materials, broken crockery, ashes, dead cats and other refuse into the streets under cover of darkness.” Ibid., 13.

- 44. Ibid., 12-13.

- 45. In this context, environmental issues were tackled, too. Gas distilleries were developed for purifying coal gas and to get rid of bad fumes and “noxious elements” like tar, carbonic acid or ammonia. Chris Otter, The Victorian Eye: A Political History of Light and Vision in Britain, 1800–1910 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), 138.

- 46. Jean-Michel Deleuil, “Du bec de gaz à l'halogène (cf. note 39).

- 47. From 1825 to 1828, it built gas infrastructures in Hannover, Berlin and Dresden. See Kühnel, Der Pionier des Lichts, 78-88 (cf. note 39).

- 48. Patrice de Moncan, Claude Heurteux, Le Paris d'Haussmann (Paris: Ed. du Mécène, 2002).

- 49. See, for instance, Walter Benjamin, “Paris, die Hauptstadt des XIX. Jahrhunderts”, in Siegfried Unseld (ed.), Illuminationen. Ausgewählte Schriften 1 (Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp, 1977), 170-184.

- 50. Edna Hernandez Gonzalez, “Comment l'illumination nocturne est devenue une politique urbaine: la circulation de modèles d'aménagement de Lyon (France) à Puebla, Morelia et San Luis Potosí (Mexique)” (Ph.D diss., Université Paris-Est, 2010).

- 51. Bouman, “Luxury and Control”, 30 (cf. note 42, my emphasis).

- 52. David E. Nye, “The transformation of American urban space. Early electric lighting, 1875–1915”, in Josiane Meier, Ute Hasenöhrl, Katharina Krause and Merle Pottharst (eds.), Urban Lighting, Light Pollution and Society (New York: Routledge, 2015); Bazerman, The Languages of Edison's Light (cf. note 40).

- 53. As Beate Binder suggests, light displays were better suited to stirring public excitement and inspired less critical cost-benefit analyses than other technological novelties, e.g. the electric motor. Beate Binder, Elektrifizierung als Vision: zur Symbolgeschichte einer Technik im Alltag (Tübingen: Tübinger Vereinigung für Volkskunde, 1999), 108.

- 54. In the course of the 20th C. early installations of arc light towers disappeared and were replaced by less blinding public illuminations. See Nye, “The transformation of American urban space…” (cf. note 52) and Binder, Elektrifizierung als Vision, (cf. note 53).

- 55. Alain Beltran, Patrice A. Carré, La fée et la servante: la société française face à l'électricité, XIXe-XXe siècle (Paris: Belin, 1991), 69. Furthermore, Charles Bazerman shows how Thomas A. Edison successfully promoted the electrification via public displays of the beloved incandescent light bulb on various occasions (cf. note 40).

- 56. Binder, Elektrifizierung als Vision, 57-58, (cf. note 53).

- 57. Thomas P. Hughes, Networks of Power. Electrification in Western Society, 1880–1930 (Baltimore, ML: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983), 363.

- 58. Binder, Elektrifizierung als Vision, 234-50 and 277, (cf. note 53).

- 59. Especially outside Paris, electricity consumption in France was „very week“ at the beginning of the 20th century. Pierre Lanthier, “L'évolution des techniques et des entreprises: le cas de l'électricité en France”, in Hubert Kiesewetter and Michael Hau (eds.), Chemins vers l'an 2000. Les processus de transformation scientifique et technique en Allemagne et en France au XXe siècle (Bern: Lang, 2000), 222.

- 60. Alain Beltran cites Bos et Laffargue: “La lumière elle-même n’est pas toujours très belle et dans beaucoup d’endroits, par exemple à Francfort, les ingénieurs n’ont pas même cherché à éviter pour l’éclairage public, dans les lampes à arc, les ombres provenant des charbons” and they conclude “L’Allemand vise à l’utilisation pratique avant tout ; peu lui importe le luxe. Chez nous c’est malheureusement le contraire”. Alain Beltran, “L'électrification de deux capitales: Paris - Berlin 1878-1939”, in Yves Cohen (ed.), Frankreich Und Deutschland : Forschung, Technologie Und Industrielle Entwicklung Im 19. Und 20. Jahrhundert (München: Beck, 1990), 285.

- 61. My translation. Ibid., 281. The same was true for the German perspective.

- 62. Beltran observes that “passée la Première Guerre mondiale, la comparaison des électrifications urbaines a pris un autre sens car dans change pays on raisonnait à une nouvelle échelle : généralement régionale dans le cas allemand et plutôt nationale dans le cas français”. Ibid., 287.

- 63. Binder, Elektrifizierung als Vision (cf. note 53) and Alain Beltran, Patrice A. Carré, La fée et la servante (cf. note 55).

- 64. Binder, Elektrifizierung als Vision, 336 (cf. note 53); David E. Nye, When the Lights Went Out: A History of Blackouts in America (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010); Karin Hirdina, Janis Augsburger (eds.), Schönes gefährliches Licht. Studien zu einem kulturellen Phänomen (Stuttgart: Ibidem, 2000).

- 65. It referred not only to nuclear power but was also “synonymous with the grandeur of France” referring “back to glorious days past, invoking Louis XIV, Napoleon, and the heyday of French imperialism”. Hecht, “Technology, politics, and national identity in France”, 260 (cf. note 4).

- 66. For instance, until 2003/2004 the City of Lyon benefited from low night-time electricity rates of €0.0757 per kWh whereas in Germany, energy prices for municipalities ranged around €0.15 per kWh. Schulte-Römer, “Innovating in Public”, 136 (cf. note 1).

- 67. See: www.lemonde.fr/economie/article/2011/01/14/veolia-et-edf-en-passe-de-pe…, last access 2018-03-20.

- 68. Schulte-Römer, “Innovating in Public” (cf. note 1), 128.

- 69. Roger Narboni, “From Light Urbanism to Nocturnal Urbanism”, Light & Engineering, vol. 24, n° 4, 2016; Gonzalez, “Comment l'illumination nocturne…” (cf. note 50), or Schulte-Römer, “Innovating in Public”, 113 (cf. note 1).

- 70. Sophie Mosser, “Eclairage urbain: enjeux et instruments d'action” (Ph.D diss, Université Paris 8, 2003), 34; Samuel Challéat and Dany Lapostolle (translated by Oliver Waine), “Getting Night Lighting Right. Taking Account of Nocturnal Urban Uses for Better-Lit Cities”, Metropolitics, 2 November 2018 (URL: https://www.metropolitiques.eu/Getting-Night-Lighting-Right.html); Jean-Michel Deleuil and Jean-Yves Toussaint, “De la sécurité à la publicité, l'art d'éclairer la ville”, Les Annales de la Recherche Urbaine, n°87, 2000.

- 71. The professionalization and standardization had already started with the candle standard in the 19th C., when the economies of gaslight called for new measuring techniques. Otter, The Victorian Eye (cf. note 45).

- 72. Bernard Barraqué, “L'éclairagisme entre art et science. Jean Dourgnon (1901 – 1985)”, in Fabienne Cardot (ed.), L'Électricité et ses consommateurs (Paris: Association pour l'histoire de l'électricité en France, 1987).

- 73. Sophie Mosser, Jean-Pierre Devars, “Quel droit de cité pour l'éclairage urbain?”, Les Annales de la Recherche Urbaine, n° 87, 2000, 65.

- 74. Michel Callon’s preface to Gabrielle Hecht, The Radiance of France (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009), xx.

- 75. As Ute Hasenöhrl points out such contestations have regularly occurred in times of transition. Hasenöhrl Ute, “Lighting conflicts from a historical perspective” in Josiane Meier, Ute Hasenöhrl, Katharina Krause and Merle Pottharst (eds.), Urban Lighting, Light Pollution and Society (New York: Routledge, 2015).

- 76. For a more detailed description of the interplay between the LED revolution and climate change mitigation policies see Schulte-Römer, “Innovating in Public” (cf. note 1).

- 77. Anne-Marie Ducroux, “L'ANPCEN. Une voix toujours pionnière”, L'Astronomie, vol. 129, n° 85, 2015.

- 78. TNS Sofres, “Les Français et les nuisances lumineuses”, September 2012, 17-18. URL: https://www.tns-sofres.com/sites/default/files/2013.02.01-lumiere.pdf.

- 79. In France, this discourse and the positive revaluation of darkness was initiated by astronomers and gained increasing public attention in the 1990s and led to the creation of the Association Nationale pour la Protection du Ciel Nocturne (ANPCN), which changed its name to ANPCEN in 2006 in order to include the concern for “l’environment nocturne” (“E”) besides the protection of night skies (“Ciel). Challéat Samuel, Lapostolle Dany, Bénos Rémy, “Consider the Darkness. From an Environmental and Sociotechnical Controversy to Innovation in Urban Lighting”, Articulo - Journal of Urban Research [Online], n° 11, 2015, 4-5 and 9. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/articulo/3064 2015 (accessed 2019-05-02).

- 80. In 2013, the French government passed an environmental law which includes measures against light pollution that were even tightened up in December 2018. See: https://www.ecologique-solidaire.gouv.fr/pollution-lumineuse, last access 2019-02-28.

- 81. Bille, Homely Atmospheres and Lighting Technologies in Denmark, 17 (cf. note 3).

- 82. There is an increasing body of social-scientific ethnographic research on the variety and ambivalence of light preferences in practice as I have outlined in a forthcoming review essay on Mikkel Bille’s and Tim Edensor’s recent monographs. Nona Schulte-Römer, “Research in the Dark. Explorations into the Societal Effects of Light and Darkness”, Nature and Culture, forthcoming. Other examples include the LSE project Configuring lights (configuringlight.org) and the French research collective RENOIR (URL: renoir.hypotheses.org, accessed 2019-03-08).

- 83. Michel Callon in Hecht, The Radiance of France (cf. note 73).

- 84. Sociologists might refer to the Thomas theorem: “If men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences.” Dorothy Swaine and William Isaac Thomas quoted in: Robert K. Merton, “The Thomas Theorem and the Matthew Effect”, Social Forces, vol. 74, n° 2, 1995, 401.

Alewyn Richard, Sälzle Karl, Das grosse Welttheater: die Epoche der höfischen Feste in Dokument und Deutung, (Reinbeck bei Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1959).

Anderson Benedict, Imagined communities (London: Verso, 1983).

Barraqué Bernard, “L'éclairagisme entre art et science. Jean Dourgnon (1901 – 1985)”, in Fabienne Cardot (ed.), L'Électricité et ses consommateurs (Paris: Association pour l'histoire de l'électricité en France, 1987), 155-178.

Bazerman Charles., The Languages of Edison's Light (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999).

Beltran Alain, “L'électrification de deux capitales: Paris - Berlin 1878-1939”, in Yves Cohen (ed.), Frankreich Und Deutschland : Forschung, Technologie Und Industrielle Entwicklung Im 19. Und 20. Jahrhundert., (München: Beck, 1990), 281-288.

Beltran Alain, Carré Patrice A., La fée et la servante: la société française face à l'électricité, XIXe-XXe siècle (Paris: Belin, 1991).

Benjamin Walter, “Paris, die Hauptstadt des XIX. Jahrhunderts”, in Siegfried Unseld (ed.), Illuminationen. Ausgewählte Schriften 1 (Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp, 1977), 170-184.

Bijker Wiebe, “The Social Construction of Fluorescent Lighting, or How an Artifact Was Invented in Its Diffusion Stage”, in Wiebe Bijker and John Law (eds.), Shaping Technology. Building Society. Studies in Sociotechnical Change (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992), 75-102.

Bille Mikkel, Homely Atmospheres and Lighting Technologies in Denmark: Living with Light (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019).

Bille Mikkel, Sørensen Tim Flohr, “An Anthropology of Luminosity: The Agency of Light”, Journal of Material Culture, vol. 12, n° 3, 2007, 263-284.

Binder B., Elektrifizierung als Vision: zur Symbolgeschichte einer Technik im Alltag (Tübingen: Tübinger Vereinigung für Volkskunde, 1999).

Bouman Mark J., “Luxury and Control”, Journal of Urban History, vol. 14, n° 1, 1987, 7-37.

Brox Jane, Brilliant: The Evolution of Artificial Light (Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010).

Challéat Samuel, Lapostolle Dany, “Getting Night Lighting Right. Taking Account of Nocturnal Urban Uses for Better-Lit Cities”, Metropolitics, 2 November 2018. https://www.metropolitiques.eu/Getting-Night-Lighting-Right.html, last access 2019-03-06.

Challéat Samuel, Lapostolle Dany, Bénos Rémy, “Consider the Darkness. From an Environmental and Sociotechnical Controversy to Innovation in Urban Lighting”, Articulo. Journal of Urban Research vol. 11, 2015, 1-17, https://doi.org/10.4000/articulo.3064.

Clegg Samuel, A practical treatise on the manufacture and distribution of coal-gas, its introduction and progressive improvement; illustrated by engravings from working drawings, with general estimates (London: Weale, 1853).

Cooper Thomas, Some Information Concerning Gas Lights (John Conrad & Company J. Maxwell, printer, 1816).

De Moncan Patrice, Heurteux Claude, Le Paris d'Haussmann (Paris: Ed. du Mécène, 2002).

Deleuil Jean-Michel, “Du bec de gaz à l'halogène. Les enjeux de l'éclairage public à Lyon”, Bulletin du Centre Pierre Léon d'histoire économique et sociale, vol.1, 1995, 17-28.

Deleuil Jean-Michal, Toussaint Jean-Yves. “De la sécurité à la publicité, l'art d'éclairer la ville”, Les Annales de la Recherche Urbaine, n° 87, 2000, 52-58.

Ducroux, Anne-Marie. "L'ANPCEN. Une Voix Toujours Pionnière." L'Astronomie, vol. 129, n° 85, 2015, 62-65.

Echinard Pierre, “De la lanterne au laser: deux cent trente ans d'éclairage public à Marseille”, unpublished LUCI conference paper – Marseille à la Loup (Marseille, 2013).

Ekirch A. Roger, At Day's Close: Night in Times Past (New York: WW Norton & Company, 2005).

Elkins James, “Precision, Misprecision, Misprision”, Critical Inquiry, vol. 25, n° 1, 1998, 169-180.

Falkus, Malcolm E., "The Early Development of the British Gas Industry, 1790–1815," The Economic History Review, vol. 35, n°2, 1982, 217-234.

Felt Ulrike, “Keeping Technologies Out: Sociotechnical Imaginaries and the Formation of Austria's Technopolitical Identity”, in Sheila Jasanoff and Sang-Hyun Kim (eds.), Dreamscapes of Modernity: Sociotechnical Imaginaries and the Fabrication of Power (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 103-125.

Figuier, Louis, Les Merveilles de la science ou description populaire des inventions modernes. [4], Éclairage, chauffage, ventilation, phares, puits artésiens, cloche à plongeur, moteur à gaz, aluminium, planète Neptune (Paris: Furne, Jouvet, 1870).

Gonzalez Edna Hernandez, “Comment l'illumination nocturne est devenue une politique urbaine: la circulation de modèles d'aménagement de Lyon (France) à Puebla, Morelia et San Luis Potosí (Mexique)” (Ph.D diss., Université Paris-Est, 2010).

Hasenöhrl Ute, “Lighting conflicts from a historical perspective” in Josiane Meier, Ute Hasenöhrl, Katharina Krause and Merle Pottharst (eds.), Urban Lighting, Light Pollution and Society (New York: Routledge, 2015), 105-124.

Hecht Gabrielle, “Technology, politics, and national identity in France”, in Michael Thad Allen and Gabrielle Hecht (eds.), Technologies of Power: Essays in Honor of Thomas Parke Hughes and Agatha Chipley Hughes (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2001), 253-293.

Hecht Gabrielle, The Radiance of France (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009).

Herlaut Auguste-Philippe, “L’Éclairage des rues à Paris à la fin du 17e et au 18e siècles”, Mémoire de la Société de l’Histoire de Paris et de l’Île de France, vol. XLIII, 1916.

Hirdina Karin, Augsburger Janis (eds.), Schönes gefährliches Licht. Studien zu einem kulturellen Phänomen (Stuttgart: Ibidem, 2000).

Hoffmann Kathryn A., Society of Pleasures: Interdisciplinary Readings in Pleasure and Power during the Reign of Louis XIV (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1997).

Hordara S., “The City of Lights, When It Was First Lighted”, The New York Times, retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/05/nyregion/the-city-of-lights-when-it-…, (2016-06-04).

Hughes Thomas P., Networks of Power. Electrification in Western Society, 1880–1930 (Baltimore, ML: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983).

Jasanoff Sheila, Kim Sang-Hyun (eds.), Dreamscapes of Modernity: Sociotechnical Imaginaries and the Fabrication of Power (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015).

Koslofsky Craig, “Court Culture and Street Lighting in Seventeenth-Century Europe”, Journal of Urban History, vol. 28, n° 6, 2002, 743-768.

Koslofsky Craig, “Princes of Darkness: The night at court, 1650–1750”, The Journal of Modern History, vol. 79, n° 2, 2007, 235-273.

Klaus Kühnel, Der Pionier des Lichts : Vom Klempnergesellen Zum Großindustriellen –Die Lebensgeschichte Des Carl Friedrich Julius Pintsch. (Berlin: Trafo, 2015)

Lanthier Pierre, “L'évolution des techniques et des entreprises: le cas de l'électricité en France”, in Hubert Kiesewetter and Michael Hau (eds.), Chemins vers l'an 2000. Les processus de transformation scientifique et technique en Allemagne et en France au XXe siècle (Bern: Lang, 2000), 221-244.

Malherbe Jean-Baptiste-Léonce et al., Rapport sur un mémoire de M. Bertulus, de Marseille, relatif à l'influence de l'éclairage au gaz sur la santé publique (Nantes : impr. de Vve C. Mellinet 1855).

Merton Robert K., “The Thomas Theorem and the Matthew Effect”, Social Forces, vol. 74, n° 2, 1995, 379-422.

Mosser Sophie, “Eclairage urbain: enjeux et instruments d'action” (Ph.D diss., Université Paris 8, 2003).

Mosser Sophie, Devars Jean-Pierre, “Quel droit de cité pour l'éclairage urbain?”, Les Annales de la Recherche Urbaine, n° 87, 2000, 63-72.

Narboni Roger, “From Light Urbanism to Nocturnal Urbanism”, Light & Engineering, vol. 24, n° 4, 2016, 19-24.

Nye David E., When the Lights Went Out: A History of Blackouts in America (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010).

Nye David E., “The transformation of American urban space. Early electric lighting, 1875–1915”, in Josiane Meier, Ute Hasenöhrl, Katharina Krause and Merle Pottharst (eds.), Urban Lighting, Light Pollution and Society (New York: Routledge, 2015), 30-45.

Otter Chris, The Victorian Eye: A Political History of Light and Vision in Britain, 1800–1910 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008).

Schivelbusch Wolfgang., “The Policing of Street Lighting”, Yale French Studies, vol. 73, 1987, 61-74.

Schivelbusch Wolfgang, Disenchanted Night. The Industrialisation of Light in the Nineteenth Century (Oxford: Berg, 1988).

Schulte-Römer Nona, Dannemann Etta, Meier Josiane, Light Pollution – a Global Discussion (Leipzig: Helmholtz-Centre for Environmental Research GmbH – UFZ, 2018), http://www.ufz.de/index.php?en=20939&ufzPublicationIdentifier=21131.

Schulte-Römer Nona, “Innovating in public. The introduction of LED lighting in Berlin and Lyon” (Ph.D diss., Technische Universität Berlin, 2015), http://dx.doi.org/10.14279/depositonce-4908.

Schulte-Römer, Nona, “Research in the Dark. Explorations into the Societal Effects of Light and Darkness”, Nature and Culture, forthcoming.

Shove Elisabeth, Comfort, Cleanliness and Convenience: The Social Organization of Normality (Oxford: Berg: 2003).

Stobart Jon, “Culture versus commerce: societies and spaces for elites in eighteenth-century Liverpool”, Journal of Historical Geography, vol. 28, n° 4, 2002, 471-485.

Tanizaki Jun'ichiro, In praise of shadows (Stony Creek, CT: Leete's Island Book, 1977 [1933]).